The Ghost Stories film comes to us off the back of a much-praised stage play of the same title by two of our finest writers, Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson: at the time it was doing the rounds some years ago, I managed to immure myself against hearing even the barest hint of what it was all about, in the hopes that I’d get to go and see it (which I didn’t) whilst having no expectations which could spoil the show. Happily, I’ve managed to go on hearing nothing at all ahead of seeing the film. This is where I think it’s only fair to extend the same courtesy to anyone who might be reading this. In order to discuss Ghost Stories in any meaningful way, I’m going to have to talk about what happens and how it plays out. This will by no means be a plot synopsis, but nonetheless this review may contain mild spoilers from here on in.

The Ghost Stories film comes to us off the back of a much-praised stage play of the same title by two of our finest writers, Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson: at the time it was doing the rounds some years ago, I managed to immure myself against hearing even the barest hint of what it was all about, in the hopes that I’d get to go and see it (which I didn’t) whilst having no expectations which could spoil the show. Happily, I’ve managed to go on hearing nothing at all ahead of seeing the film. This is where I think it’s only fair to extend the same courtesy to anyone who might be reading this. In order to discuss Ghost Stories in any meaningful way, I’m going to have to talk about what happens and how it plays out. This will by no means be a plot synopsis, but nonetheless this review may contain mild spoilers from here on in.

The basic set-up is this: lapsed Jew Professor Philip Goodman (Nyman) has spent his professional and academic life trying to compensate for an unhappy upbringing, where his family’s religious values clashed with the world as he came to understand it. After a revelatory moment as a child watching the TV sceptic Charles Cameron disproving all manner of supernatural phenomena, citing people’s ‘existential terror’ as the reason they are so ready to believe in the impossible, Goodman sets to very similar work, dismantling people’s beliefs for a TV show of his very own (in an uncomfortable early scene where he storms the stage at a spiritual mediumship event, further devastating an already devastated bereaved mother in the process; it seems the medium and the sceptic are all too ready to tread on her feelings for their own agendas, and I found it one of the hardest scenes in the film to watch.)

The funny thing is, Cameron himself had disappeared into obscurity in mysterious circumstances of his own decades previously – so Goodman is astounded to receive (earthly) communication from the still-living Cameron (Leonard Byrne) who wants to speak with him. He tells Goodman that, during his professional career, he encountered three cases which assured him that his whole world view had been wrong – that there were things out there which cannot be easily explained. Investigate them for yourself, he tells the younger man, and then come and talk to me. Duly, though with the somewhat frustrated air of a man who has met one of his heroes and come away disappointed, Goodman agrees to seek out and speak to the people in each case.

Ah, the portmanteau film: it’s well known that Nyman, and Dyson (as can be seen from the earliest League of Gentlemen days) are big fans of 70s heyday British horror, and the three-in-one framework here is worthy – and reminiscent – of the old Amicus films. In each of the three stories Goodman hears, we are transported into the situation each new man reports; these cover a range of different phenomena. Tony Matthews (Paul Whitehouse) relates a story of a frightening experience as a nightwatchman; Simon Rifkind (Alex Lawther) talks about what goes on in the woods, and finally businessman Mike Priddle (Martin Freeman) explains about a night he felt deeply unsafe at home…in each case, Goodman is primed to dismiss their accounts as the ramblings of trauma, addiction, guilt, grief – you name it. But then odd phenomena begin to leech into his own life, and he’s forced to examine his own motivations, as he comes to terms with how he has impacted upon the lives of others.

There are a great many things in favour of this film, and chief amongst those is – for me – in its visual trickery. The flashy BOO! scenes which punctuate the film (no doubt after the stage play, which itself probably picked up a lot of cues from that stalwart of horror theatre, The Woman in Black) I could take or leave. I find them too easy to see coming, too much more about the reflexes than the imagination. However, what these BOO! moments certainly do achieve is to set you on edge, so that your brain is ready to see things which aren’t there. I haven’t read up on the making of the film, but I’m willing to bet all or at least most of these tricks of the eye are deliberate. ‘The brain sees what it wants to see’, and so on. There are also several nods to other classic British ghost tales – which I won’t name here – but these work with the tales at hand, and don’t feel unnecessarily tacked on. I tell you what else I thought of, and I might be alone in this, but if you’ve ever read the (terrifying) series of books issued by Fortean Times called ‘It Happened To Me’, where utterly ordinary people write in with their supernatural experiences – some of the tales in the film are strongly reminiscent of stories I’ve read there, particularly the middle story, though this may of course be entirely coincidental. In any case, it’s great to see a cast of such well-known British actors, often comedy actors, taking on something quite as dark as Ghost Stories and doing a superb job, even managing to blend in a few moments of gallows humour without dissipating the horror.

There are a great many things in favour of this film, and chief amongst those is – for me – in its visual trickery. The flashy BOO! scenes which punctuate the film (no doubt after the stage play, which itself probably picked up a lot of cues from that stalwart of horror theatre, The Woman in Black) I could take or leave. I find them too easy to see coming, too much more about the reflexes than the imagination. However, what these BOO! moments certainly do achieve is to set you on edge, so that your brain is ready to see things which aren’t there. I haven’t read up on the making of the film, but I’m willing to bet all or at least most of these tricks of the eye are deliberate. ‘The brain sees what it wants to see’, and so on. There are also several nods to other classic British ghost tales – which I won’t name here – but these work with the tales at hand, and don’t feel unnecessarily tacked on. I tell you what else I thought of, and I might be alone in this, but if you’ve ever read the (terrifying) series of books issued by Fortean Times called ‘It Happened To Me’, where utterly ordinary people write in with their supernatural experiences – some of the tales in the film are strongly reminiscent of stories I’ve read there, particularly the middle story, though this may of course be entirely coincidental. In any case, it’s great to see a cast of such well-known British actors, often comedy actors, taking on something quite as dark as Ghost Stories and doing a superb job, even managing to blend in a few moments of gallows humour without dissipating the horror.

However, the weight of expectation with films like this, particularly after having waited so long to find out what all the fuss was about, means I do have some nagging issues with the film as a whole. [Final warning on spoilers ahead.] Firstly, I understand completely that the writers want to resolve things in such a way that they don’t simply cede to the whole ‘and it was REAL!’ shtick, any more than it’d be sane to roll credits on a Bobby Ewing ending, but to get us to this quite neat – yes, clever – yes, but still ambiguous ending, I felt the film was…well, the only way I can explain it is to say it’s reactionary, in the sense that it turns all of these stories and fears into the residual agonies of a suicidal man, and in fact the whole film seems to point to him wanting to die and going through all of this purgatorial suffering because of something he didn’t do as a terrified, victimised child. It’s hardly the most eloquent thing to say, but it feels so… mean-spirited somehow, even though I am fully aware that a horror film has no duty to be nice and even-handed. I’m also torn on the whole ‘fourth wall’ thing in the final act – always a fraught decision, even if a useful bridging device between straightforward supernatural horror and the existential torture of the ending.

So, for me, Ghost Stories is a film which does many things superbly well, pays its dues, certainly kept my attention, led to some fantastically creepy moments, but also slathers on a veneer of human nastiness that I am finding unusually bitter, in a way which actually surprises me.

Ghost Stories (2017) is on general release in UK cinemas now.

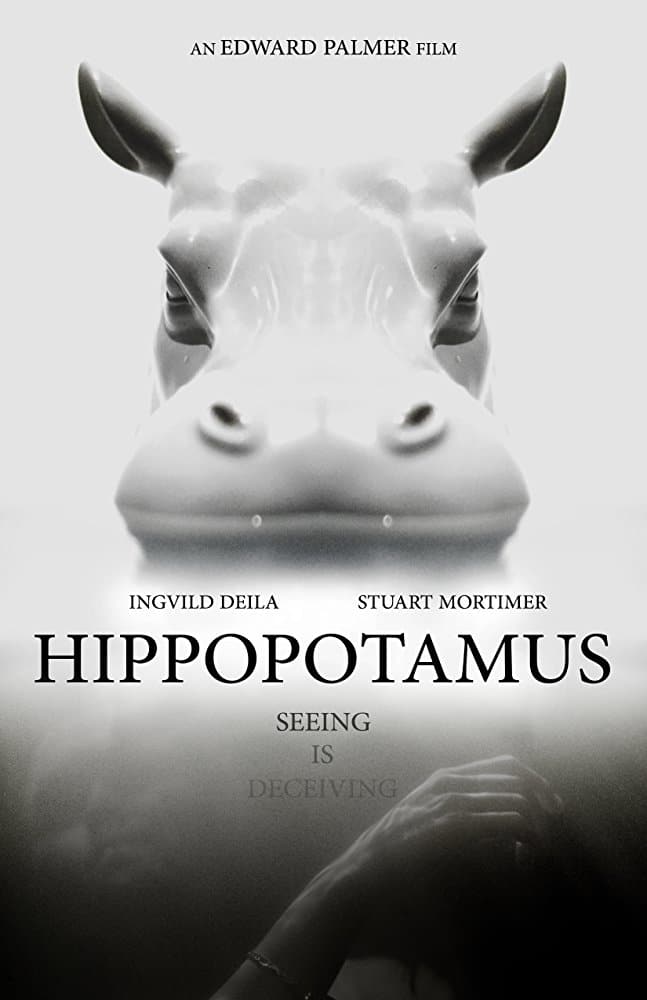

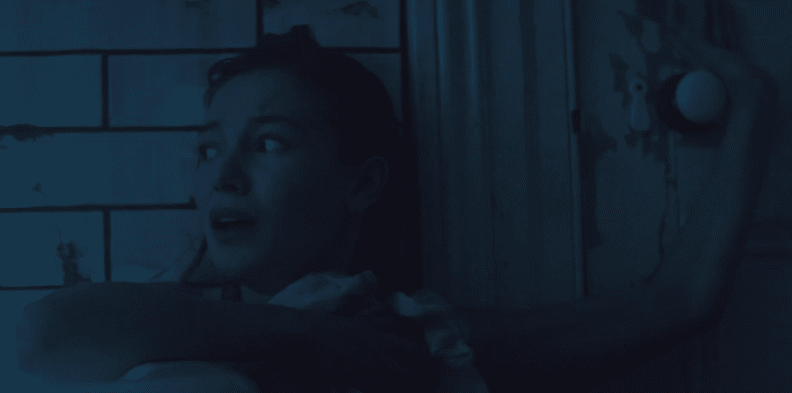

In a stark opening scene, composed largely from a colour palette of black, white, and tiny amounts of red – a young woman awakens. She is in a mysterious room, has crippling injuries to her legs, and is clearly shocked and confused by her predicament. As soon as she wakes up, she’s addressed by a man: he gives his name, explains that she has been kidnapped, and she will remain in this room until such time as she “falls in love” with him. Before leaving her alone, he warns her not to try and escape – her legs are too damaged, the place they’re in is too isolated and she won’t get far.

In a stark opening scene, composed largely from a colour palette of black, white, and tiny amounts of red – a young woman awakens. She is in a mysterious room, has crippling injuries to her legs, and is clearly shocked and confused by her predicament. As soon as she wakes up, she’s addressed by a man: he gives his name, explains that she has been kidnapped, and she will remain in this room until such time as she “falls in love” with him. Before leaving her alone, he warns her not to try and escape – her legs are too damaged, the place they’re in is too isolated and she won’t get far. The woman in captivity – Ruby – is told by her captor – Thomas – that she will be following a strict new schedule. She will be fed, she will be given medication, she will be slowly helped to heal, and her sleep will be controlled. It’s soon clear that Ruby has no idea who she is: she keeps looking with wonder at a bracelet engraved with her name, and when she gets to look at some of her possessions, kept in a nearby handbag, she’s confused by them, too. As she begins to feel more well, she begins to ask questions of Thomas, though he is not exactly forthcoming (captors in cinema rarely seem particularly garrulous). He does assure her, though, that he hasn’t kidnapped with any sexual intentions; Ruby can barely believe this, asking several times if she has been assaulted. She doesn’t endure any further cruelty, though, which begins to encourage her to dig deeper; she becomes increasingly confident with this man, and he begins to warm to her.

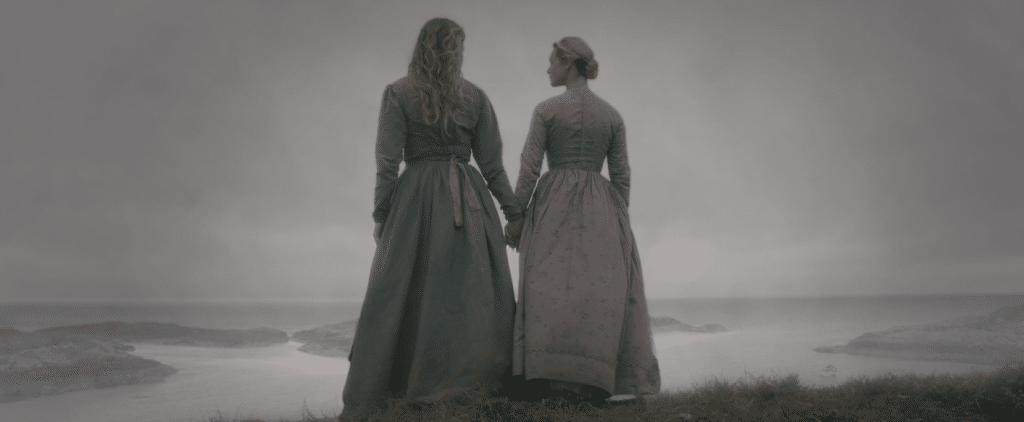

The woman in captivity – Ruby – is told by her captor – Thomas – that she will be following a strict new schedule. She will be fed, she will be given medication, she will be slowly helped to heal, and her sleep will be controlled. It’s soon clear that Ruby has no idea who she is: she keeps looking with wonder at a bracelet engraved with her name, and when she gets to look at some of her possessions, kept in a nearby handbag, she’s confused by them, too. As she begins to feel more well, she begins to ask questions of Thomas, though he is not exactly forthcoming (captors in cinema rarely seem particularly garrulous). He does assure her, though, that he hasn’t kidnapped with any sexual intentions; Ruby can barely believe this, asking several times if she has been assaulted. She doesn’t endure any further cruelty, though, which begins to encourage her to dig deeper; she becomes increasingly confident with this man, and he begins to warm to her. The year is 1846. After surviving a devastating shipwreck whilst en route to America, three men manage to make it to dry land – which turns out to be a remote Scottish island, where only a handful of people seem to live, eking out an existence. However, the first islander to greet them – a man named Fingal MacLeod (Dickon Tyrell) – seems genuinely interested in their welfare, offering them food and shelter whilst asking what exactly befell their vessel. The sailors find that difficult to explain: a sudden turn in the weather made it impossible for them to navigate, they recall, but beyond that, they aren’t sure. Fingal promises to help them get back to the mainland regardless, and suggests they stay at the local farmhouse in the meantime. Grateful for the surly assistance of the Innis household, Oliver (Alex Hassell), Cailean (Fisayo Akinade) and Jimmy (Graham Butler) can do little but wait it out.

The year is 1846. After surviving a devastating shipwreck whilst en route to America, three men manage to make it to dry land – which turns out to be a remote Scottish island, where only a handful of people seem to live, eking out an existence. However, the first islander to greet them – a man named Fingal MacLeod (Dickon Tyrell) – seems genuinely interested in their welfare, offering them food and shelter whilst asking what exactly befell their vessel. The sailors find that difficult to explain: a sudden turn in the weather made it impossible for them to navigate, they recall, but beyond that, they aren’t sure. Fingal promises to help them get back to the mainland regardless, and suggests they stay at the local farmhouse in the meantime. Grateful for the surly assistance of the Innis household, Oliver (Alex Hassell), Cailean (Fisayo Akinade) and Jimmy (Graham Butler) can do little but wait it out. The film also takes its time in establishing characters, allowing them to build in an organic way without using line after line of exposition. Seeing the characters measured against the stark, but beautiful location seems to add a great deal to how we see them, too, and this requires almost no dialogue to be spoken at all. The unmistakeable Scottish landscape dwarfs the people on this island, both outsiders and residents, reminding the audience of how little agency they have in this unforgiving environment. More than this, the rocks, woods and beaches also figure hugely in the narrative: being lost, being trapped and being disorientated are states which propel the plot onwards in their own ways. And, before the film unfolds its surprises, finally revealing its secrets (The Isle’s changes in direction are genuinely surprising and engaging) we are kept on the same level as the characters themselves – never truly sure whether this bleak place can be taken on face value.

The film also takes its time in establishing characters, allowing them to build in an organic way without using line after line of exposition. Seeing the characters measured against the stark, but beautiful location seems to add a great deal to how we see them, too, and this requires almost no dialogue to be spoken at all. The unmistakeable Scottish landscape dwarfs the people on this island, both outsiders and residents, reminding the audience of how little agency they have in this unforgiving environment. More than this, the rocks, woods and beaches also figure hugely in the narrative: being lost, being trapped and being disorientated are states which propel the plot onwards in their own ways. And, before the film unfolds its surprises, finally revealing its secrets (The Isle’s changes in direction are genuinely surprising and engaging) we are kept on the same level as the characters themselves – never truly sure whether this bleak place can be taken on face value. Marriage in the nineteenth century – particularly between the lower middle classes, perhaps, who had enough to lose but little enough to boast – must have been for many women a miserable existence. Firstly, women often had limited influence on the matches proposed to them, having to consider the fortune of their families and dependents as well as themselves, when respectable opportunities to earn money were very limited. The Married Woman’s Property Acts did not come in until 1870 and beyond; until that time, women forfeited any land, property or money they had in their own names, passing it directly to their husbands at the point of marriage. They had no legal rights to their own children – the father de facto retained that right – and limited access even to the extreme solution of divorce which, in the rare cases it took place, frequently led to women being socially ostracised, shunned by neighbours and family, and of course penniless, if they had no other arrangement or allowance entailed upon them. The only legitimate, respectable way out of a middle-class marriage was widowhood.

Marriage in the nineteenth century – particularly between the lower middle classes, perhaps, who had enough to lose but little enough to boast – must have been for many women a miserable existence. Firstly, women often had limited influence on the matches proposed to them, having to consider the fortune of their families and dependents as well as themselves, when respectable opportunities to earn money were very limited. The Married Woman’s Property Acts did not come in until 1870 and beyond; until that time, women forfeited any land, property or money they had in their own names, passing it directly to their husbands at the point of marriage. They had no legal rights to their own children – the father de facto retained that right – and limited access even to the extreme solution of divorce which, in the rare cases it took place, frequently led to women being socially ostracised, shunned by neighbours and family, and of course penniless, if they had no other arrangement or allowance entailed upon them. The only legitimate, respectable way out of a middle-class marriage was widowhood. Knowing the young bride is alone in the house one night, Sebastian takes his chance and sneaks in, giving the lie to the absent Alexander’s assertion that Katherine will be ‘safer’ there. At first, Katherine acts the part of the valiant virgin, trying to repel what seems a would-be rape – but then, subverting the expected codes of behaviour, she inverts the situation, suddenly reciprocating his advances. Sebastian suddenly has to re-assess, finding himself no longer in the stereotypical male role; he might have expected her to behave more like Anna perhaps, who even as a social inferior is demure enough to be mortified. Respectable women at this time were supposed to be passive, and virtually asexual – only submitting to the act for the purpose of maternity. Dr William Acton, practitioner to Queen Victoria, wrote a famous paper in 1857 – so, contemporary with the film – where he claimed that ‘the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind’: certainly, Sebastian is surprised by the way Katherine responds, and it’s not what he would have expected. It is also the moment that his own agency begins to rescind, irreparably, whilst hers blossoms – at least, up until a point.

Knowing the young bride is alone in the house one night, Sebastian takes his chance and sneaks in, giving the lie to the absent Alexander’s assertion that Katherine will be ‘safer’ there. At first, Katherine acts the part of the valiant virgin, trying to repel what seems a would-be rape – but then, subverting the expected codes of behaviour, she inverts the situation, suddenly reciprocating his advances. Sebastian suddenly has to re-assess, finding himself no longer in the stereotypical male role; he might have expected her to behave more like Anna perhaps, who even as a social inferior is demure enough to be mortified. Respectable women at this time were supposed to be passive, and virtually asexual – only submitting to the act for the purpose of maternity. Dr William Acton, practitioner to Queen Victoria, wrote a famous paper in 1857 – so, contemporary with the film – where he claimed that ‘the majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled by sexual feelings of any kind’: certainly, Sebastian is surprised by the way Katherine responds, and it’s not what he would have expected. It is also the moment that his own agency begins to rescind, irreparably, whilst hers blossoms – at least, up until a point. There’s no simple answer here, but it’s worth remembering that she is not the only woman whose lot in life is pinioned by her social role. Anna, the lady’s maid, is a liminal figure in the film who is often present at key moments, but utterly peripheral, unable to influence things one way or another. She tries – valiantly – but she is in the unenviable position of being on the lowest rung here, the only person Katherine can command with propriety and impunity. There’s an interesting relationship between the two women, one which moves from some degree of intimacy to complete alienation. As Katherine’s sense of agency escalates, Anna’s already-limited agency diminishes – to the point when the girl becomes utterly voiceless in the face of the crimes she is forced to witness.

There’s no simple answer here, but it’s worth remembering that she is not the only woman whose lot in life is pinioned by her social role. Anna, the lady’s maid, is a liminal figure in the film who is often present at key moments, but utterly peripheral, unable to influence things one way or another. She tries – valiantly – but she is in the unenviable position of being on the lowest rung here, the only person Katherine can command with propriety and impunity. There’s an interesting relationship between the two women, one which moves from some degree of intimacy to complete alienation. As Katherine’s sense of agency escalates, Anna’s already-limited agency diminishes – to the point when the girl becomes utterly voiceless in the face of the crimes she is forced to witness. I feel as though I’ve been here before. Not just because there was a film called Bong of the Dead a few years ago, which my co-editor Ben reviewed, nor indeed because this very day

I feel as though I’ve been here before. Not just because there was a film called Bong of the Dead a few years ago, which my co-editor Ben reviewed, nor indeed because this very day  Eventually, the zombie thing intrudes a bit more forcefully into their home when a zombie gets to one of them (and it’s not as if they’re walled in, by the way – one of the characters pops in and out whenever he wants). This darkens the mood rather suddenly. To dispel the fairly static scenes which preceded this sudden spike in drama, Bong of the Living Dead now dispenses with the loud, wild-eyed intonation which came before and tries to segue into sentimentality for a while – something which just doesn’t mesh well.

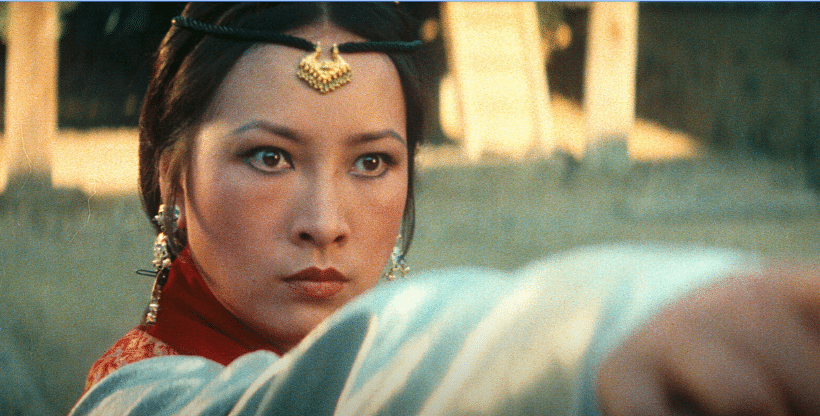

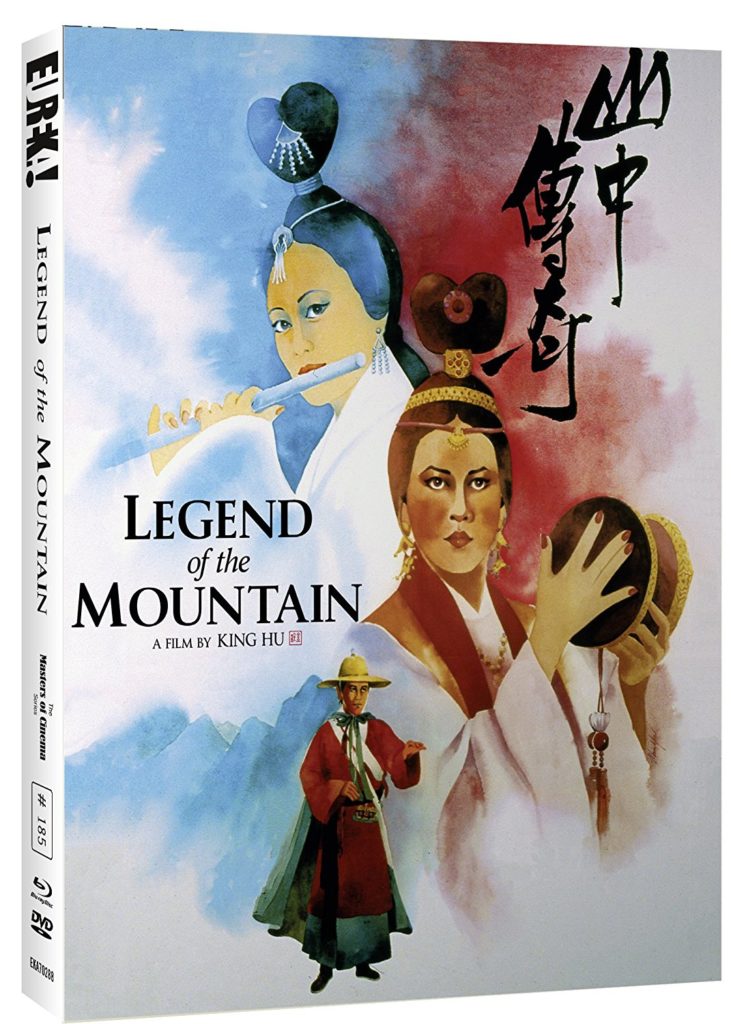

Eventually, the zombie thing intrudes a bit more forcefully into their home when a zombie gets to one of them (and it’s not as if they’re walled in, by the way – one of the characters pops in and out whenever he wants). This darkens the mood rather suddenly. To dispel the fairly static scenes which preceded this sudden spike in drama, Bong of the Living Dead now dispenses with the loud, wild-eyed intonation which came before and tries to segue into sentimentality for a while – something which just doesn’t mesh well. Whilst I have something of a handle on Japanese cinema of the 70s and 80s – well, in so far as the films have made the great leap to Western screens – I know comparatively little about Chinese cinema of the same period, and in that I have to include Hong Kong/Taiwan. I’ve seen a couple of hopping vampires (hopping because they still have their winding sheets on) and a handful of crime dramas, but not a lot else. Compared to Japan, China, HK and Taiwan are, by and large, a closed book. I’m aware, though, that the director of Legend of the Mountain, King Hu, moved from acting to directing, and that the film under consideration here is oft considered to be his magnum opus. An epic it certainly is; rocking in at over three hours, it’s a lengthy, visually incredibly accomplished Chinese folk tale, which uses its ample screen time to do a great deal of quite disparate things along the way.

Whilst I have something of a handle on Japanese cinema of the 70s and 80s – well, in so far as the films have made the great leap to Western screens – I know comparatively little about Chinese cinema of the same period, and in that I have to include Hong Kong/Taiwan. I’ve seen a couple of hopping vampires (hopping because they still have their winding sheets on) and a handful of crime dramas, but not a lot else. Compared to Japan, China, HK and Taiwan are, by and large, a closed book. I’m aware, though, that the director of Legend of the Mountain, King Hu, moved from acting to directing, and that the film under consideration here is oft considered to be his magnum opus. An epic it certainly is; rocking in at over three hours, it’s a lengthy, visually incredibly accomplished Chinese folk tale, which uses its ample screen time to do a great deal of quite disparate things along the way. This entire project screams classic China: abundant landscapes are presented in a highly colourised, painterly manner, and traditional Chinese instrumentation accompanies the action throughout. Then, of course, the subject matter itself is based on ancient folklore, and to an extent this film is a piece of Far Eastern folk horror, albeit that the film never settles into this mode completely. Supernatural elements underpin the story, and the director works hard within his means to produce some subtle, uncanny scenes. But this film is many other things, to the extent that it never really takes its place in any genre, in an expected sense. It has an eye for historical detail, but also flits between being a pastoral, a romance, a reminiscence and – when it’s not adding comedic elements and the obligatory martial arts scenes to this melee – it even dabbles in Buddhist philosophy, ruminating on life, love and everything. Overall, Legend of the Mountain does a great, great deal. Well, the film is immensely long, and I’ll say it, as ever; it’s rather too long for my tastes, and despite its pleasant visuals and overall engaging subject matter, it veers from cramming in more and more plot elements to lengthy, even unnecessary forays through the woods. As it’s nearly forty years old, I can’t even say it’s falling in behind the new tendency to make films increasingly longer.

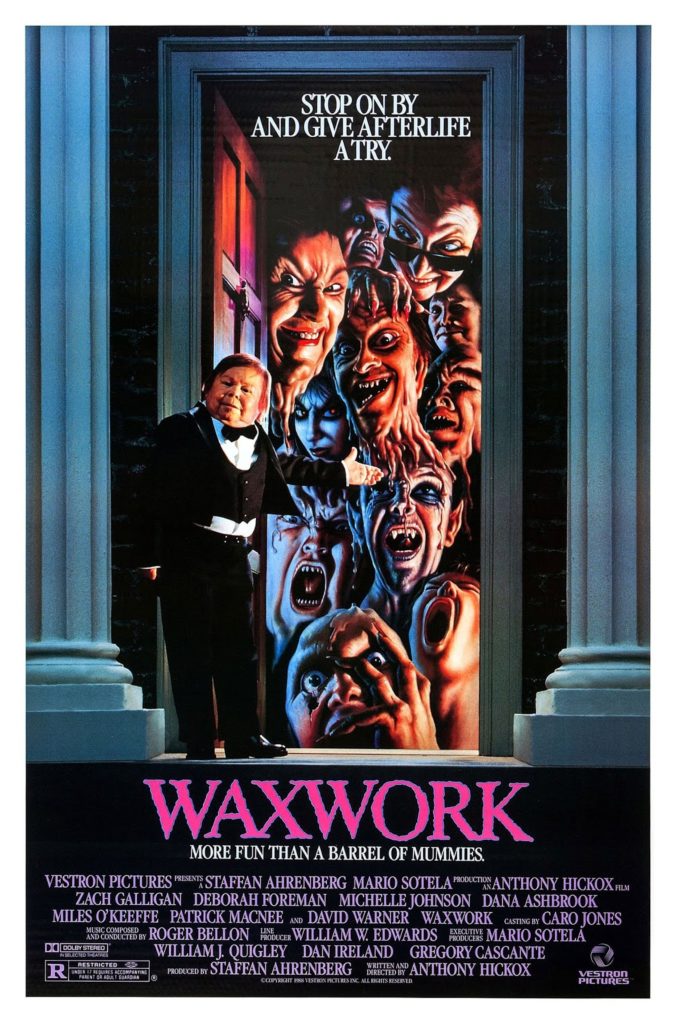

This entire project screams classic China: abundant landscapes are presented in a highly colourised, painterly manner, and traditional Chinese instrumentation accompanies the action throughout. Then, of course, the subject matter itself is based on ancient folklore, and to an extent this film is a piece of Far Eastern folk horror, albeit that the film never settles into this mode completely. Supernatural elements underpin the story, and the director works hard within his means to produce some subtle, uncanny scenes. But this film is many other things, to the extent that it never really takes its place in any genre, in an expected sense. It has an eye for historical detail, but also flits between being a pastoral, a romance, a reminiscence and – when it’s not adding comedic elements and the obligatory martial arts scenes to this melee – it even dabbles in Buddhist philosophy, ruminating on life, love and everything. Overall, Legend of the Mountain does a great, great deal. Well, the film is immensely long, and I’ll say it, as ever; it’s rather too long for my tastes, and despite its pleasant visuals and overall engaging subject matter, it veers from cramming in more and more plot elements to lengthy, even unnecessary forays through the woods. As it’s nearly forty years old, I can’t even say it’s falling in behind the new tendency to make films increasingly longer. But in the 80s – a whole thirty years ago, to be precise – a film used the theme of the waxwork museum as its central plot device; not only that, but it was one of the first truly self-referential horror films, doing far more than simply utilising the waxwork museum as a straightforwardly scary setting. Whilst sharing some plot features with House of Wax, Waxwork also runs stories within stories, eventually pitching these stories against the world as we know it. It’s ambitious, it’s novel – and it’s such fun.

But in the 80s – a whole thirty years ago, to be precise – a film used the theme of the waxwork museum as its central plot device; not only that, but it was one of the first truly self-referential horror films, doing far more than simply utilising the waxwork museum as a straightforwardly scary setting. Whilst sharing some plot features with House of Wax, Waxwork also runs stories within stories, eventually pitching these stories against the world as we know it. It’s ambitious, it’s novel – and it’s such fun. The nature of each waxwork tableau is significant. Each functioning as a distinct story (and I’d honestly have happily seen each and any of them turned into a film of their own) the waxworks feature a panoply of entertainment and horror film archetypes: there are circus acts, historical murders, Gothic fantasies and a whole host of famous monsters. In the first sequence, the werewolf story even references Universal’s take on the werewolf myth, using the ubiquitous silver bullets which were the invention of the 1930s script. Later on, we come up against mummies, vampires, zombies, even the Phantom of the Opera: the whole film is a love-letter to both old and new horror, with a cast of older actors, several of whom, like Patrick Macnee, had long worked in horror cinema, featuring alongside new actors like Zach Galligan – fresh out of the hit kiddie horror Gremlins, and forever associated with this decade in film.

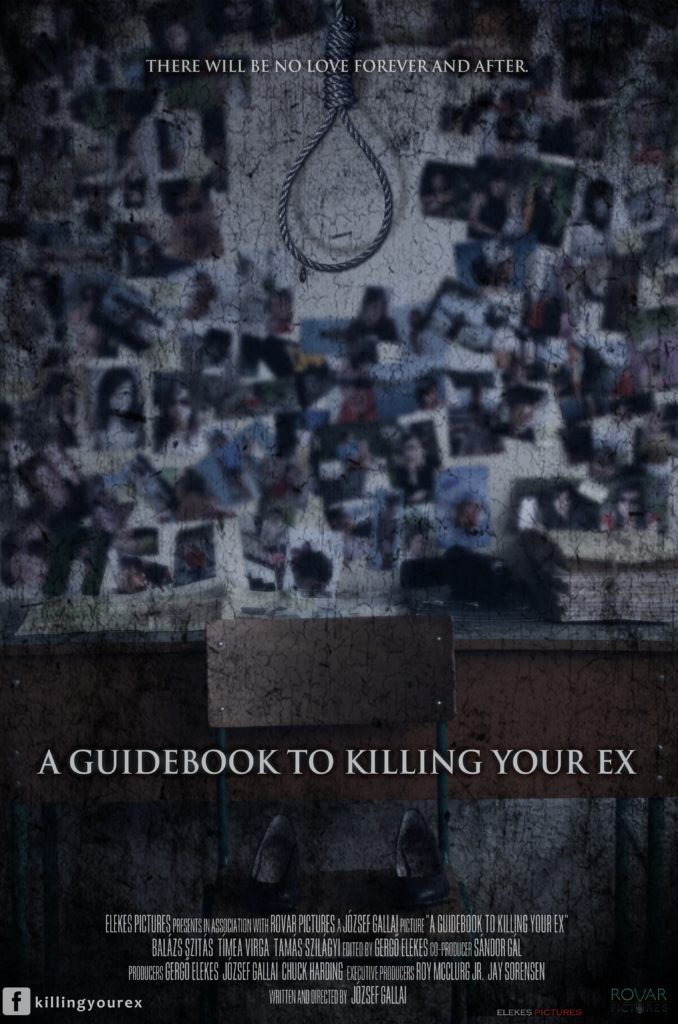

The nature of each waxwork tableau is significant. Each functioning as a distinct story (and I’d honestly have happily seen each and any of them turned into a film of their own) the waxworks feature a panoply of entertainment and horror film archetypes: there are circus acts, historical murders, Gothic fantasies and a whole host of famous monsters. In the first sequence, the werewolf story even references Universal’s take on the werewolf myth, using the ubiquitous silver bullets which were the invention of the 1930s script. Later on, we come up against mummies, vampires, zombies, even the Phantom of the Opera: the whole film is a love-letter to both old and new horror, with a cast of older actors, several of whom, like Patrick Macnee, had long worked in horror cinema, featuring alongside new actors like Zach Galligan – fresh out of the hit kiddie horror Gremlins, and forever associated with this decade in film. Is it just me, or does the ‘found footage’ craze of the past fifteen years or so seem to have died back a little of late? This sub-genre seemed to dominate indie cinema for what seemed like forever, becoming infamous as a go-to model for those on a shoestring budget. Well, found footage films are still out there and they’re still being made, though to be fair, a Hungarian ‘horror comedy’ found footage is a new one on me. This would be A Guidebook to Killing your Ex, then, written and directed by

Is it just me, or does the ‘found footage’ craze of the past fifteen years or so seem to have died back a little of late? This sub-genre seemed to dominate indie cinema for what seemed like forever, becoming infamous as a go-to model for those on a shoestring budget. Well, found footage films are still out there and they’re still being made, though to be fair, a Hungarian ‘horror comedy’ found footage is a new one on me. This would be A Guidebook to Killing your Ex, then, written and directed by  The decision to use the found footage framing style makes sense here in many respects, though in common with many other films within this genre, there are a few head-scratching moments. These completed films (this one held in police files post-case) apparently pop up in the form we see them, which suggests (as above) that some sort of editing is going on before films are recovered or, perhaps, that those who find the films edit them into some sort of shape before they’re seen – in which case, the inclusion of things such as John Doe tucking into a meal are odd things to keep in. See also: someone speaking the immortal line “What is the camera for?” Maybe I’m alone in getting hung up on these points, but I think it’s interesting; standard, edited-by-omniscient-storyteller films don’t bring these issues with them. I mentioned that the film had much in common with the ‘mumblecore’ genre, too, and it would seem that lots of the dialogue is improvised – though Doe does look off camera from time to time rather than into it, which means, perhaps, that he is looking at cues. This improvised dialogue – which is reasonably sparky and engaging – is far easier to see as associated with mumblecore than it is to see the film as a whole as a comedy, or a straightforward horror for that matter. There are some absurd elements which veer towards humorous, and in terms of horror there is some slightly grisly footage, but overall, A Guidebook to Killing Your Ex feels a lot more like an experimental , dialogue-heavy film than either a horror or a comedy. Its refusal to sit comfortably in either of the bigger genres is to some extent a strength, but may mean it’s trickier for the film to find its audience.

The decision to use the found footage framing style makes sense here in many respects, though in common with many other films within this genre, there are a few head-scratching moments. These completed films (this one held in police files post-case) apparently pop up in the form we see them, which suggests (as above) that some sort of editing is going on before films are recovered or, perhaps, that those who find the films edit them into some sort of shape before they’re seen – in which case, the inclusion of things such as John Doe tucking into a meal are odd things to keep in. See also: someone speaking the immortal line “What is the camera for?” Maybe I’m alone in getting hung up on these points, but I think it’s interesting; standard, edited-by-omniscient-storyteller films don’t bring these issues with them. I mentioned that the film had much in common with the ‘mumblecore’ genre, too, and it would seem that lots of the dialogue is improvised – though Doe does look off camera from time to time rather than into it, which means, perhaps, that he is looking at cues. This improvised dialogue – which is reasonably sparky and engaging – is far easier to see as associated with mumblecore than it is to see the film as a whole as a comedy, or a straightforward horror for that matter. There are some absurd elements which veer towards humorous, and in terms of horror there is some slightly grisly footage, but overall, A Guidebook to Killing Your Ex feels a lot more like an experimental , dialogue-heavy film than either a horror or a comedy. Its refusal to sit comfortably in either of the bigger genres is to some extent a strength, but may mean it’s trickier for the film to find its audience. The very opening scenes of The Lodgers speak to the key themes of the film as a whole: a young woman, sitting alone by a lake at night, preoccupied by her thoughts, suddenly flees back to a dilapidated mansion house when she hears the clock striking midnight. This is the first, but not the last nod to the darker side of fairy stories; stories which the film references in abundance. Especial menace surrounds a trapdoor in the house, which bubbles and threatens with dark water as the girl returns; there are sinister forces at work here, and the girl is obviously terrified.

The very opening scenes of The Lodgers speak to the key themes of the film as a whole: a young woman, sitting alone by a lake at night, preoccupied by her thoughts, suddenly flees back to a dilapidated mansion house when she hears the clock striking midnight. This is the first, but not the last nod to the darker side of fairy stories; stories which the film references in abundance. Especial menace surrounds a trapdoor in the house, which bubbles and threatens with dark water as the girl returns; there are sinister forces at work here, and the girl is obviously terrified. Meanwhile, an Irishman who has been away fighting for the British in World War One returns to the village, going home to his family business – the local grocers. This is Sean (Eugene Simon – best known as cousin Lancel from Game of Thrones, the Lannister who goes full Sparrow). His reappearance causes inevitable ripples of anger around town, coming as it does at a particularly heated time in Anglo-Irish relations; however, as his mother owns the only shop in the area, he soon meets the distinctly aloof Rachel, though his initial attraction to the girl is clear. Rachel, meanwhile, receives a letter from England which jeopardises her and her brother’s isolated existence in the house, and as her oppressive home life becomes even more unbearable, even terrifying, she no longer repels Sean’s attempts to help.

Meanwhile, an Irishman who has been away fighting for the British in World War One returns to the village, going home to his family business – the local grocers. This is Sean (Eugene Simon – best known as cousin Lancel from Game of Thrones, the Lannister who goes full Sparrow). His reappearance causes inevitable ripples of anger around town, coming as it does at a particularly heated time in Anglo-Irish relations; however, as his mother owns the only shop in the area, he soon meets the distinctly aloof Rachel, though his initial attraction to the girl is clear. Rachel, meanwhile, receives a letter from England which jeopardises her and her brother’s isolated existence in the house, and as her oppressive home life becomes even more unbearable, even terrifying, she no longer repels Sean’s attempts to help. I think everyone must remember the first time they saw Dead Alive – or, to give it its UK title, Braindead, where it released in the spring of the same year (May). There are other titles in use, all of which show that distribution companies took the film very much in the spirit it was intended. As well as the expected variants on ‘braindead’, in Spain a line of dialogue from the film gives us the title, Your Mother Ate My Dog; in Brazil, they opted for Animal Hunger; Hungary, a literal nation, simply went for Corpse! (exclamation mark included). All in all, the variety of titles around the globe do a fair job of summing up the film’s plot and vibe.

I think everyone must remember the first time they saw Dead Alive – or, to give it its UK title, Braindead, where it released in the spring of the same year (May). There are other titles in use, all of which show that distribution companies took the film very much in the spirit it was intended. As well as the expected variants on ‘braindead’, in Spain a line of dialogue from the film gives us the title, Your Mother Ate My Dog; in Brazil, they opted for Animal Hunger; Hungary, a literal nation, simply went for Corpse! (exclamation mark included). All in all, the variety of titles around the globe do a fair job of summing up the film’s plot and vibe. It’s the 1950s, and a naturalist expedition into Skull Island, Sumatra (ring any bells?) to find a specimen of a rare species – a ‘rat monkey’ – ends in a bloody incident which can’t be patched up, not even with a bit of Dettol. These little buggers are dangerous, it seems, being the warped offspring of local monkeys and slave-ship rats, and only amputation (even of the head) can be used to treat their bites successfully. Lesson duly noted. Back home in New Zealand, overbearing mother Vera divides up her time between Wellington Ladies Welfare League duties and stopping her grown-up son Lionel from growing up any more than is strictly necessary. When he starts dating a local girl, Paquita, Lionel decides to take her for a lovely day at the zoo. Vera, who isn’t too keen on her son fraternising with an Experienced Girl like Paquita, goes along to spy on them. Our rat monkey friend is by now installed and on display, but when Vera gets too close to its cage, it sinks its teeth into her, ruining her dress into the bargain. It looks as if she’s won this round, as Lionel immediately escorts his injured mother home, but she soon falls sick. Really sick. And it seems as though whatever condition she’s picked up from the monkey, it’s contagious. Lionel is one of life’s copers, but he soon loses control of the situation, despite doing what he can to keep his mother (and some unwitting houseguests) ‘calm’. Except, oh, he makes a singular error, prompting the closing sequence to end all closing sequences…

It’s the 1950s, and a naturalist expedition into Skull Island, Sumatra (ring any bells?) to find a specimen of a rare species – a ‘rat monkey’ – ends in a bloody incident which can’t be patched up, not even with a bit of Dettol. These little buggers are dangerous, it seems, being the warped offspring of local monkeys and slave-ship rats, and only amputation (even of the head) can be used to treat their bites successfully. Lesson duly noted. Back home in New Zealand, overbearing mother Vera divides up her time between Wellington Ladies Welfare League duties and stopping her grown-up son Lionel from growing up any more than is strictly necessary. When he starts dating a local girl, Paquita, Lionel decides to take her for a lovely day at the zoo. Vera, who isn’t too keen on her son fraternising with an Experienced Girl like Paquita, goes along to spy on them. Our rat monkey friend is by now installed and on display, but when Vera gets too close to its cage, it sinks its teeth into her, ruining her dress into the bargain. It looks as if she’s won this round, as Lionel immediately escorts his injured mother home, but she soon falls sick. Really sick. And it seems as though whatever condition she’s picked up from the monkey, it’s contagious. Lionel is one of life’s copers, but he soon loses control of the situation, despite doing what he can to keep his mother (and some unwitting houseguests) ‘calm’. Except, oh, he makes a singular error, prompting the closing sequence to end all closing sequences… More than this, Dead Alive is confident enough in itself to do a few new things with the idea of the zombie. Lionel has his hands full with the little house gathering he ends up with, but probably didn’t expect to have to contend with two of them falling for each other. The only people consummating anything in the film are corpses; weirder still, these corpses end up doting on a new arrival soon afterwards. Cinema had brought us monster offspring, but never clowning like this. Parenthood doesn’t exactly get an easy run in the film, at any point, and forging the guise of a happy family gives us one of the film’s most outrageous scenes. Baby Selwyn – with Lionel haplessly trying to look after him – gives us the best parody of the proud parental walk in the park, probably ever, especially when Lionel starts punching the little bleeder before shoving him in a duffle bag, under the astonished eye of a gathering of genteel looking women. “Hyperactive,” apparently. There’s still a shock value in having a character doing anything to ‘The Children’, even if one of them is a zombie, so this is another expectation Jackson plays fast and loose with, as well as showcasing Timothy Balme’s tremendous skills as a decent man on the edge of losing his mind. When I first saw the park sequence, I had to watch it again straight away. I wasn’t sure if I had really seen a man doing that with/to a pram. (I re-watched the sequence to write this feature, and yep, it’s still enough to make me cry laughing. I mean, how could you not?)

More than this, Dead Alive is confident enough in itself to do a few new things with the idea of the zombie. Lionel has his hands full with the little house gathering he ends up with, but probably didn’t expect to have to contend with two of them falling for each other. The only people consummating anything in the film are corpses; weirder still, these corpses end up doting on a new arrival soon afterwards. Cinema had brought us monster offspring, but never clowning like this. Parenthood doesn’t exactly get an easy run in the film, at any point, and forging the guise of a happy family gives us one of the film’s most outrageous scenes. Baby Selwyn – with Lionel haplessly trying to look after him – gives us the best parody of the proud parental walk in the park, probably ever, especially when Lionel starts punching the little bleeder before shoving him in a duffle bag, under the astonished eye of a gathering of genteel looking women. “Hyperactive,” apparently. There’s still a shock value in having a character doing anything to ‘The Children’, even if one of them is a zombie, so this is another expectation Jackson plays fast and loose with, as well as showcasing Timothy Balme’s tremendous skills as a decent man on the edge of losing his mind. When I first saw the park sequence, I had to watch it again straight away. I wasn’t sure if I had really seen a man doing that with/to a pram. (I re-watched the sequence to write this feature, and yep, it’s still enough to make me cry laughing. I mean, how could you not?) My relationship with the Hellraiser sequels is ambivalent at best, hostile at worst; as I’ve said previously, the first Hellraiser

My relationship with the Hellraiser sequels is ambivalent at best, hostile at worst; as I’ve said previously, the first Hellraiser  In the melee, there are some decent ideas here. The idea of an affinity between deviants and demons is of course nothing new, but exploring it in a modern, urban setting still has some promise, lending old Judeo-Christian ideas a grimy horror patina. The idea of being judged at the Pearly Gates is transformed into a demonic admin exercise here – it’s different, and it has potential. Although the presence of T&A doesn’t exactly fit in with the other monsters in this mythos, these scenes are book-ended with material which gets close to the dark, maggoty horror of the first two Hellraisers, and a few moments in the script display some love and knowledge of the source material, which at least shows that Tunnicliffe isn’t just winging it here. As for Pinhead himself, well – when he’s on screen, he’s…okay. He’s blank, rather than malevolent; his garb has obviously been simplified for reasons of expediency, but the make-up is reasonably good. We have to remember that Doug Bradley wasn’t exactly able to shine in his last few appearances in his hallmark role, either, so as far as the sequels go, Taylor does a reasonable job with what he has.

In the melee, there are some decent ideas here. The idea of an affinity between deviants and demons is of course nothing new, but exploring it in a modern, urban setting still has some promise, lending old Judeo-Christian ideas a grimy horror patina. The idea of being judged at the Pearly Gates is transformed into a demonic admin exercise here – it’s different, and it has potential. Although the presence of T&A doesn’t exactly fit in with the other monsters in this mythos, these scenes are book-ended with material which gets close to the dark, maggoty horror of the first two Hellraisers, and a few moments in the script display some love and knowledge of the source material, which at least shows that Tunnicliffe isn’t just winging it here. As for Pinhead himself, well – when he’s on screen, he’s…okay. He’s blank, rather than malevolent; his garb has obviously been simplified for reasons of expediency, but the make-up is reasonably good. We have to remember that Doug Bradley wasn’t exactly able to shine in his last few appearances in his hallmark role, either, so as far as the sequels go, Taylor does a reasonable job with what he has.