As the point has been made several times before on this site, horror comedy can be a risky venture; when it goes wrong, it can be either not that funny, nor really capable of showing any love for the horror genre either. Happily, neither of these charges can be levelled at Extra Ordinary. The film uses a full, recognisable array of horror tropes, and yet also manages to craft something very plausible, because in the midst of all the madness there are some organic human relationships which work in all their lunatic (usually) dysfunctional glory. There’s also an Irish lilt to the humour, much as the filmmakers deliberately swerved around the use of Irish stereotypes (spoiler: there are no priests here and there’s no boozing either). But for all that, there still is something unique about how the film moves between the very straightforward and the oblique, something which feels very Irish to me and which makes the film the genuinely funny experience it is.

Our first introduction to the Dooley sisters, Rose (comedian Maeve Higgins) and Sailor (Terri Chandler) comes via a VHS clip from the days when their now sadly-departed father investigated the paranormal. We’re shown that Rose blames herself for her father’s death, but Sailor assures her that it was just an accident; in any case, Rose had followed her father into paranormal investigation, but has since opted for a rather more orthodox career as a driving instructor. The problem is, people in the local area are still convinced that they need Rose’s help with their paranormal problems; most of these are hilariously low-key, but then there’s Martin’s case…

Martin (Barry Ward) is plagued by the spirit of his deceased wife Bonnie. She has strong feelings on what he does around the house, right down to what he wears every day, and Martin has little choice but to follow her wishes. Whilst their teenage daughter Sarah is largely left alone by Bonnie, she can see that her father needs some serious help in order to move on, or to move Bonnie on – which is largely the same thing. Eventually, under the auspices of having a driving lesson (!) Martin gets in contact with Rose. Rose’s own loneliness is a factor in her decision-making. This would be quite enough, but it seems there’s more trouble at hand for the Martin family – and, yep, Martin’s name is Martin Martin. When Sarah is bewitched by a [deep breath] washed-up vocalist whose only big hit was decades previously, leading to his decision to use the Dark Arts to resurrect his career, then Rose feels honour-bound to help them.

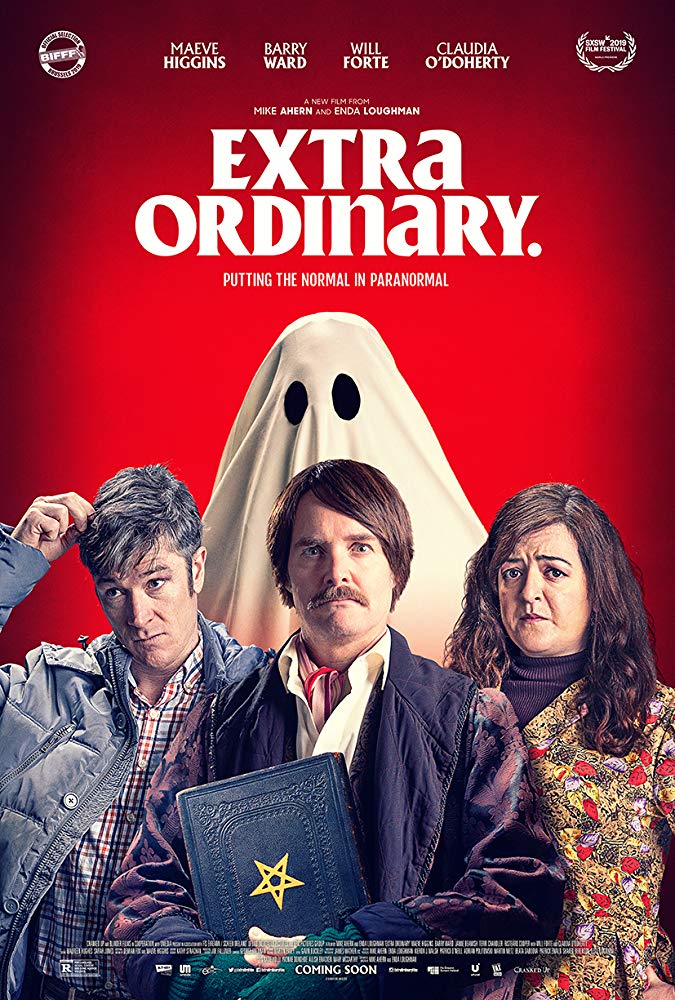

So we have a little haunting, a little paranormal investigation, a dash of possession, and some Satanic ritual to boot. There’s even a bit of gore here. I challenge you to be bored. All of that said, the film starts incredibly small in terms of its paranormal phenomena, opening with the point that most hauntings are so insignificant that people don’t even notice them (and Rose’s dad pointing out that even something as small as ‘a gravel’ can be affected gave us an early laugh). It’s just that things don’t stay small. I’ve no wish to spoiler, but, well – you know rituals. Underpinning all of this, and the reason that the film never feels like an aimless sprint through a hell of a lot of plot, is that there’s such plausible, poignant characterisation. Sure, the performance given by faded music star Christian Winter (Will Forte) is as OTT as you’d expect, but this acts as a foil to the performances of Barry Ward and Maeve Higgins. Higgins was offered the opportunity to modify the script to make it sound more natural where she felt it was necessary, and this does add a lot of likeability and depth to the characterisation. In amongst everything else which is going on, you can suspend your disbelief as the people here just work so well.

Extra Ordinary is ambitious in what it seeks to do (and how it steadily reveals elements of its plot in the run-up to its closing scenes) and it has created an original, very engaging story from recognisable horror elements. No complaints here: this is a horror comedy that works brilliantly well, with bags of charm and deserved self-belief.

Extra Ordinary screened at the Mayhem Film Festival in Nottingham in October 2019 and will be released in UK cinemas on 25th October 2019.