It’s always a privilege, in these social media-saturated times, to walk into a film screening without the faintest idea of what it’s all about. As I hadn’t even looked at the Celluloid Screams programme before we sat down to watch Habit (and as I almost immediately mix up titles and synopses anyway) it definitely felt like a boon that I had zero expectations, allowing the film to speak entirely for itself. I’m about to stop this being the case for anyone reading, though, by offering the barest of synopses here: Habit is a dark urban crime thriller which gradually adds horror elements, a claustrophobic and nightmarish tale which perhaps overstretches itself in some key regards, but still deserves credit for many of the things it does very well.

It’s always a privilege, in these social media-saturated times, to walk into a film screening without the faintest idea of what it’s all about. As I hadn’t even looked at the Celluloid Screams programme before we sat down to watch Habit (and as I almost immediately mix up titles and synopses anyway) it definitely felt like a boon that I had zero expectations, allowing the film to speak entirely for itself. I’m about to stop this being the case for anyone reading, though, by offering the barest of synopses here: Habit is a dark urban crime thriller which gradually adds horror elements, a claustrophobic and nightmarish tale which perhaps overstretches itself in some key regards, but still deserves credit for many of the things it does very well.

Mikey (Elliot James Langridge) is a bit of a harmless deadbeat, lurching from dole office (where he arrives late) to pub, to club, where he spends all the money he’s just been given and starts again. This all seems to stem from a traumatic childhood experience, a few moments of which we are shown in the opening scenes, but he and his older sister Amanda (Sally Carman) have remained close into adulthood, as much as she’s completely exasperated with his inability to sort himself out. A chance meeting one day throws him into the path of Lee (Jessica Barden), a teenage girl who seems to have nowhere else to go. She promptly installs herself in the life (and flat) of him and his housemate, and the pair soon grow closer.

One day, Mikey accompanies Lee on a visit to her uncle Ian (William Ash), which happens to be in a massage parlour down a dark side-street in Manchester’s city centre. Her uncle seems to be something of a wheeler-dealer, but he helps his niece out and takes an interest in Mikey. Mikey, in good part, takes a keen interest in one of the girls working there, and returns on his own later that night for a promised ‘special offer’. The night doesn’t quite go to plan, though, when he witnesses a violent attack on another man using the premises. Ian’s tactic is to bring Mikey into the fold, offering him a job as a doorman. Mikey needs the money, so he agrees, steadily growing closer to his employer and the rest of the staff in the process, whilst questioning what ‘family’ really means along the way.

Still, this isn’t exactly a legal establishment. Things are going on, and – gradually – Mikey has his eyes opened to what these things are.

Some strong and largely plausible performances allow Habit to generate a sensation of slowly-ratcheting tension, with particular praise here for Langridge, whose turn as an essentially decent young man adrift maintained my interest throughout. The gangland characters were believably menacing, and the dialogue overall did convey, in Mancunian accents, this idea of something bigger and more profoundly wrong going on behind the scenes. So far, so good. The Manchester sights and sounds may call to mind the kinds of gritty TV drama, or indeed the gritty comedy, for which the city is better-known, but that’s only to be expected – regional dialects often crop up this way in the media. I do have to pause on Jessica Barden’s portrayal of Lee though, while we’re on the topic of believability: her tones were a little too cut-glass to really believe she had grown up sofa-surfing in Greater Manchester, but then elements of her writing didn’t help her either – first she’s the innocent bystander whose uncle just wants to keep her out of the mucky business of prostitution, then in a heartbeat, she’s involved after all. Still, these issues didn’t stop me engaging with the film as such, although they gave me pause for thought.

There are plenty of other things which I unequivocally enjoyed about Habit. What’s certainly impressive about the film is how the rain-lashed Manchester nightscapes appear on screen. This is a strong visual feature in the film, with a variety of shots which really make the film feel firmly rooted in its Northern England environment. In some scenes the city looks bustling and alive; in others, the rundown old industrial buildings and dark corners look like something straight out of a dystopia. I’ve always felt like there’s something special about Northern cities with their ‘dark Satanic mills’, even if these mills have been refurbished and let out as plush apartments now. It’s somehow pleasing to see these places represented on screen, even if it’s not necessarily as somewhere relentlessly upbeat. God, where’s the interest in that, anyway?

Still, as much as this isn’t a straightforward horror yarn, it makes sense to talk about the horror that’s there. To give credit where credit’s due, I had suspected some sort of fantastical twist was coming, but the one that turned up wasn’t what I expected. This, in and of itself, is a plus, although the decision to take the film in an entirely new direction brings risks of its own.

The next two paragraphs could be considered a spoiler, so skip it if you want things to remain a complete surprise. I feel I have to mention the following, though, as the comparison to another film I’m about to make seems integral to a criticism I need to make about Habit.

I feel that the newer film owes many of its cues to We Are What We Are, whether the original or the (very competent) Jim Mickle ‘reimagining’ of same, which stayed fairly true to source. In We Are What We Are, the ‘ritual’ which united the loving, but clearly dysfunctional family unit was a surprise and a complication which eventually leads to their undoing; it’s a very, very similar case in Habit. The addition of this maybe-supernatural, definitely-deviant behaviour was, the first time I saw it, an interesting motif which has usually only made it to the screen in the form of mondo documentaries or what is as near to ‘classic’ exploitation cinema as we have, the likes of Ferox et al.

However, as engaging as this new treatment of the cannibalism theme is in We Are What We Are, it brings with it some issues. A little, even just a little more explanation would have benefited the film/s enormously; this doesn’t mean that all loose ends need to be tied up, but some of this would have added a deeper level of understanding for the characters and their motivations. Now, here is where someone on the Habit filmmaking team contacts me to tell me that none of them have even heard of We Are What We Are, so perhaps – perhaps – this may be pure coincidence, but to my mind, the issues which dog the older film cause some of the same issues in Habit. I’d like to know just that shade more about what motivates the characters, or how ‘the family’ were brought together in the first place. If their behaviour makes them feel alive in some new and exciting way, then why, and how does it do so? Admittedly, I don’t know the novel which Habit is based on – this may reveal far more, but going by the film alone is what many, if not most of the film’s viewers will be doing.

However, as engaging as this new treatment of the cannibalism theme is in We Are What We Are, it brings with it some issues. A little, even just a little more explanation would have benefited the film/s enormously; this doesn’t mean that all loose ends need to be tied up, but some of this would have added a deeper level of understanding for the characters and their motivations. Now, here is where someone on the Habit filmmaking team contacts me to tell me that none of them have even heard of We Are What We Are, so perhaps – perhaps – this may be pure coincidence, but to my mind, the issues which dog the older film cause some of the same issues in Habit. I’d like to know just that shade more about what motivates the characters, or how ‘the family’ were brought together in the first place. If their behaviour makes them feel alive in some new and exciting way, then why, and how does it do so? Admittedly, I don’t know the novel which Habit is based on – this may reveal far more, but going by the film alone is what many, if not most of the film’s viewers will be doing.

For all that this issue casts a slight shadow over the motivations of the characters in the film, however, I did enjoy the escalating nastiness of Habit. It’s now that I come to write my review that I realise how much I did enjoy it, actually. Ultimately it’s all about belonging, and the savage things people will participate in to feel that. It also touches on a very real source of horror – the ways in which people on the fringes of society can simply disappear without trace – and as such, it riffs on the idea of consumption in a brutal and visceral way.

I’ve followed the careers of directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead with interest ever since I covered their challenging and innovative feature debut,

I’ve followed the careers of directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead with interest ever since I covered their challenging and innovative feature debut,  The Endless is not shy of grappling with themes which are terrifying enough in their complexity at the best of times, adding its palpable sense of unease by slow, expertly-wrought degrees. Our vulnerability to something vast and humbling like time itself has long been a source of horror, so the addition of – potentially – a pernicious unknown behind the scenes is both unsettling and ambitious. Linked to this is the idea that personal freedom itself is dubious – something else we don’t like to dwell on, something else that scares us. It would be easy to throw in the word ‘Lovecraftian’ here, and yes, there are a few key moments where that author comes to mind; I’d argue there are some links with his short story, The Unnamable [sic] amongst others. And, like Lovecraft, The Endless knows better than to straightforwardly show its hand. Retaining elements of mystery is key to the film’s success.

The Endless is not shy of grappling with themes which are terrifying enough in their complexity at the best of times, adding its palpable sense of unease by slow, expertly-wrought degrees. Our vulnerability to something vast and humbling like time itself has long been a source of horror, so the addition of – potentially – a pernicious unknown behind the scenes is both unsettling and ambitious. Linked to this is the idea that personal freedom itself is dubious – something else we don’t like to dwell on, something else that scares us. It would be easy to throw in the word ‘Lovecraftian’ here, and yes, there are a few key moments where that author comes to mind; I’d argue there are some links with his short story, The Unnamable [sic] amongst others. And, like Lovecraft, The Endless knows better than to straightforwardly show its hand. Retaining elements of mystery is key to the film’s success. Being a tiny nation, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Iceland hasn’t yet featured very prominently, in its own right, in cinema. Its stunning and evocative landscapes have been used a thousand times in films which simply seek a striking location, but it’s comparatively rare to see Icelandic people, language and stories making their own way to the screen – at least for audiences outside of the country. For this reason alone, it’s welcome to see I Remember You (

Being a tiny nation, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Iceland hasn’t yet featured very prominently, in its own right, in cinema. Its stunning and evocative landscapes have been used a thousand times in films which simply seek a striking location, but it’s comparatively rare to see Icelandic people, language and stories making their own way to the screen – at least for audiences outside of the country. For this reason alone, it’s welcome to see I Remember You ( How these two stories will intertwine is kept quiet for a large share of the film, with each story generating its own interest (and several low-key scares); course, you can probably gather that they will, eventually, overlap, and to give credit to writer/director Óskar Thór Axelsson, it’s quite hard to predict the process. That said, it feels like a long road to get to this point: the film runs at 105 minutes, which in today’s climate is not that long at all, but given the deliberation and pace of I Remember You, it feels somewhat longer. If you have patience for these kinds of slow-burn thrillers, then I would say there’s plenty there to reward it, but if you prefer your films more tightly-wrought then you may also feel that this film meanders in places.

How these two stories will intertwine is kept quiet for a large share of the film, with each story generating its own interest (and several low-key scares); course, you can probably gather that they will, eventually, overlap, and to give credit to writer/director Óskar Thór Axelsson, it’s quite hard to predict the process. That said, it feels like a long road to get to this point: the film runs at 105 minutes, which in today’s climate is not that long at all, but given the deliberation and pace of I Remember You, it feels somewhat longer. If you have patience for these kinds of slow-burn thrillers, then I would say there’s plenty there to reward it, but if you prefer your films more tightly-wrought then you may also feel that this film meanders in places. For many of us growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, being terrified by the Borley Rectory hauntings was practically a rite of passage. For my part, I must have been around nine years old, I’d guess, and found out about ‘the most haunted house in England’ from a Readers’ Digest Mysteries of the Unexplained compendium. There were other tales of ghostly phenomena which also fascinated and appalled me – the Matthew Manning story, the Bell Witch case – but the allegedly ghostly scrawls addressed to ‘Marianne’ really fixed themselves in my imagination. I couldn’t bring myself to re-read the section on Borley Rectory for weeks at a time, but thought about it constantly, even beginning to practise my own automatic writing after I read about its use in Borley – thus, terrifying myself even more.

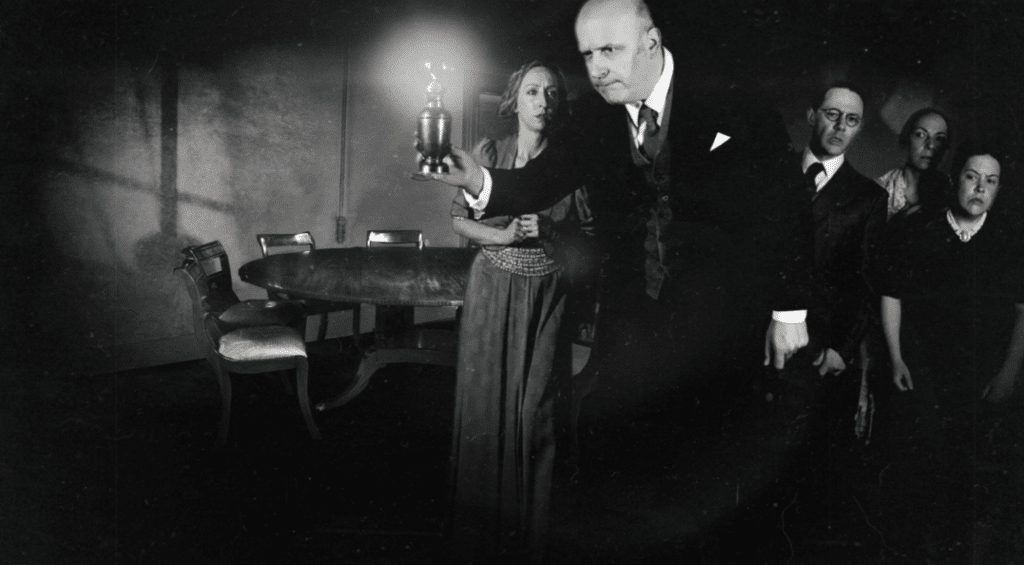

For many of us growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, being terrified by the Borley Rectory hauntings was practically a rite of passage. For my part, I must have been around nine years old, I’d guess, and found out about ‘the most haunted house in England’ from a Readers’ Digest Mysteries of the Unexplained compendium. There were other tales of ghostly phenomena which also fascinated and appalled me – the Matthew Manning story, the Bell Witch case – but the allegedly ghostly scrawls addressed to ‘Marianne’ really fixed themselves in my imagination. I couldn’t bring myself to re-read the section on Borley Rectory for weeks at a time, but thought about it constantly, even beginning to practise my own automatic writing after I read about its use in Borley – thus, terrifying myself even more. Borley Rectory (2017) is unusually framed as a documentary film, exploring and discussing the events mentioned above in largely linear order with the help of a narrator – none other than Julian Sands. Ashley Thorpe explained at the screening that his film had been heavily influenced by his own childhood nostalgia for spooky 70s TV, such as the works of Lawrence Gordon Clark and the Armchair Thriller series, which had a scary ghost nun of its own. I’m sure I saw some Ghost Story for Christmas artwork tucked away in one of the sequences, too. However, Thorpe also mentioned a love of 1920s and 30s Hollywood horror, which seems altogether heavier in the mix: Borley Rectory is shot entirely in black and white, and the actors wear the heavily stylised costumes and make-up beloved of, say, early James Whale cinema. Whilst it’s somewhat engaging to see some well-beloved actors both dressed in period costume and acting accordingly – with Reece Shearsmith as the Daily Mirror reporter, Nicholas Vince as Reverend Smith and author Jonathan Rigby as Price himself, the rather studied delivery somewhat dwarfs any stylistic links to the barely-glimpsed horrors of Gordon Clark.

Borley Rectory (2017) is unusually framed as a documentary film, exploring and discussing the events mentioned above in largely linear order with the help of a narrator – none other than Julian Sands. Ashley Thorpe explained at the screening that his film had been heavily influenced by his own childhood nostalgia for spooky 70s TV, such as the works of Lawrence Gordon Clark and the Armchair Thriller series, which had a scary ghost nun of its own. I’m sure I saw some Ghost Story for Christmas artwork tucked away in one of the sequences, too. However, Thorpe also mentioned a love of 1920s and 30s Hollywood horror, which seems altogether heavier in the mix: Borley Rectory is shot entirely in black and white, and the actors wear the heavily stylised costumes and make-up beloved of, say, early James Whale cinema. Whilst it’s somewhat engaging to see some well-beloved actors both dressed in period costume and acting accordingly – with Reece Shearsmith as the Daily Mirror reporter, Nicholas Vince as Reverend Smith and author Jonathan Rigby as Price himself, the rather studied delivery somewhat dwarfs any stylistic links to the barely-glimpsed horrors of Gordon Clark. The legacy of Catholicism in French and Belgian left-field cinema seems to mean a strange predilection for Christian themes, although it finds its form in curious ways. In recent years we’ve had Calvaire, made in 2004 (retitled ‘The Ordeal’ for English audiences, which neatly strips it of its Biblical meaning), the Christmas creation horrors of Satan (2006) and of course Martyrs (2008). Now, ten years later, we have something which merges crime drama with something altogether more spiritual and not a little gonzo: voila, Doubleplusungood.

The legacy of Catholicism in French and Belgian left-field cinema seems to mean a strange predilection for Christian themes, although it finds its form in curious ways. In recent years we’ve had Calvaire, made in 2004 (retitled ‘The Ordeal’ for English audiences, which neatly strips it of its Biblical meaning), the Christmas creation horrors of Satan (2006) and of course Martyrs (2008). Now, ten years later, we have something which merges crime drama with something altogether more spiritual and not a little gonzo: voila, Doubleplusungood. The film, for all its unusual contextual factors, is however broadly linear: it takes its unconventional elements on a pretty straightforward journey through a series of kills, which can feel repetitive, despite the film’s efforts to draw down interest via its inventively-nasty sequences. The film certainly steers away from conventional style or approach throughout: it’s thoughtfully shot, with a wide range of locales and lots of artistic, experimental detail (even veering into psychedelia on occasion). There is undeniably something of the new-wave of French/Belgian horror cinema in the way Doubleplusungood looks, with lots of that blueish colourisation, though it’s still far more of a crime thriller overall. That said, we do see a bit of ‘implement torture’ going on here, which also chimes with those new wave horrors.

The film, for all its unusual contextual factors, is however broadly linear: it takes its unconventional elements on a pretty straightforward journey through a series of kills, which can feel repetitive, despite the film’s efforts to draw down interest via its inventively-nasty sequences. The film certainly steers away from conventional style or approach throughout: it’s thoughtfully shot, with a wide range of locales and lots of artistic, experimental detail (even veering into psychedelia on occasion). There is undeniably something of the new-wave of French/Belgian horror cinema in the way Doubleplusungood looks, with lots of that blueish colourisation, though it’s still far more of a crime thriller overall. That said, we do see a bit of ‘implement torture’ going on here, which also chimes with those new wave horrors. Honestly, I’m the sort of reviewer who thinks that the vast majority of slashers (and many gialli) are better enjoyed as still images than films – being largely an array of stylish, bloody set pieces only loosely linked by some sort of plot – so watching Sergio Martino’s crossover film Torso was an opportunity for me to test my misgivings about this type of catch ’em and kill ’em horror. His other work has been pretty diverse fare in its way, after all, and a who’s who of cult film stars helps to underpin the potential of the film under discussion. Worth a shot, right?

Honestly, I’m the sort of reviewer who thinks that the vast majority of slashers (and many gialli) are better enjoyed as still images than films – being largely an array of stylish, bloody set pieces only loosely linked by some sort of plot – so watching Sergio Martino’s crossover film Torso was an opportunity for me to test my misgivings about this type of catch ’em and kill ’em horror. His other work has been pretty diverse fare in its way, after all, and a who’s who of cult film stars helps to underpin the potential of the film under discussion. Worth a shot, right? All of that said, Torso does achieve many things which distinguish it against a crowded field of carved-up nubile flesh. It boasts beautiful locations (mind, Italian cities seem to do the hard work by themselves) and some scenes border on the supernatural, in ways beloved of Martino’s near-contemporary Michele Soavi. It’s also an incredibly tactile film, with close attention to small details; whilst the gore FX haven’t aged particularly well, they’re very brief, whilst interesting, unusual shots (such as a woman’s hands palpating mud) show artistic flair. And, after moving all of its pieces into position for benefit of the big whodunnit, the film generates tension very effectively: yes, this takes time, but the closing twenty minutes or so give a good pay-off for all that has come before, resulting in a genuinely gripping finale. I’m not sure I can say that Torso has won me over fully to this style of filmmaking, but certainly, this is an arresting example of its genre, which manages some real surprises, in amongst the various nods to Bava et al.

All of that said, Torso does achieve many things which distinguish it against a crowded field of carved-up nubile flesh. It boasts beautiful locations (mind, Italian cities seem to do the hard work by themselves) and some scenes border on the supernatural, in ways beloved of Martino’s near-contemporary Michele Soavi. It’s also an incredibly tactile film, with close attention to small details; whilst the gore FX haven’t aged particularly well, they’re very brief, whilst interesting, unusual shots (such as a woman’s hands palpating mud) show artistic flair. And, after moving all of its pieces into position for benefit of the big whodunnit, the film generates tension very effectively: yes, this takes time, but the closing twenty minutes or so give a good pay-off for all that has come before, resulting in a genuinely gripping finale. I’m not sure I can say that Torso has won me over fully to this style of filmmaking, but certainly, this is an arresting example of its genre, which manages some real surprises, in amongst the various nods to Bava et al. 1970s cinema has many noteworthy qualities, but amongst these, the decade is certainly remarkable for its brief, but intriguing phase of imagining animals ‘going rogue’ and attacking humans; some of the resulting films were breakthrough hits, such as Jaws (1975), whereas some, such as Day of the Animals (1977) would be long-lost to obscurity if the DVD age hadn’t decided seeing Leslie Nielsen wrestling a grizzly bear was too good to pass up. Before sharks, bears and other beasts were redressing the natural balance, however, there was Willard (1971) – a film where it’s the humble rat who’s up to no good, though all at the behest of a rather lonely young man. I suppose the initial premise makes some sense: compare the number of people killed by sharks to the number killed by rats over the centuries, and the rat is definitely king – though to be fair to rats, they’ve simply been clearing up after Man for millennia, fighting over the same resources, often dying of the same things, whilst not being particularly deferential along the way.

1970s cinema has many noteworthy qualities, but amongst these, the decade is certainly remarkable for its brief, but intriguing phase of imagining animals ‘going rogue’ and attacking humans; some of the resulting films were breakthrough hits, such as Jaws (1975), whereas some, such as Day of the Animals (1977) would be long-lost to obscurity if the DVD age hadn’t decided seeing Leslie Nielsen wrestling a grizzly bear was too good to pass up. Before sharks, bears and other beasts were redressing the natural balance, however, there was Willard (1971) – a film where it’s the humble rat who’s up to no good, though all at the behest of a rather lonely young man. I suppose the initial premise makes some sense: compare the number of people killed by sharks to the number killed by rats over the centuries, and the rat is definitely king – though to be fair to rats, they’ve simply been clearing up after Man for millennia, fighting over the same resources, often dying of the same things, whilst not being particularly deferential along the way. In the sequel, Willard’s rat posse have escaped and decided to go it alone, moving into the sewers beneath the city. Forging a link to Willard before it, people establish that Ben is the leader of the rats via some pages from Willard’s diary (which we never saw him keep, but hey.) This eventually throws them into the path of a young lad, Danny, who is being bullied and suffers from a heart condition: Danny befriends Ben in particular, and Ben – who is already rather comfortable with people – becomes his best mate/avenging angel, protecting him from the bullies. Thing is, Ben the rat isn’t always a force for good. Ben and his crew aren’t too keen on human intervention in their now-habitat, and anyone making the mistake gets attacked by a whirlwind of flying rodents; again, probably not safe terrain for a phobic.

In the sequel, Willard’s rat posse have escaped and decided to go it alone, moving into the sewers beneath the city. Forging a link to Willard before it, people establish that Ben is the leader of the rats via some pages from Willard’s diary (which we never saw him keep, but hey.) This eventually throws them into the path of a young lad, Danny, who is being bullied and suffers from a heart condition: Danny befriends Ben in particular, and Ben – who is already rather comfortable with people – becomes his best mate/avenging angel, protecting him from the bullies. Thing is, Ben the rat isn’t always a force for good. Ben and his crew aren’t too keen on human intervention in their now-habitat, and anyone making the mistake gets attacked by a whirlwind of flying rodents; again, probably not safe terrain for a phobic. Truth be told, neither Willard nor Ben are superb films and Ben is the weaker, but they’re certainly quite unlike anything else, and they have had some influence elsewhere. Willard even got a fairly glossy remake/’reimagining’ in the Noughties featuring cult actor Crispin Hellion Glover, so its reach was definitely there. Willard, in particular, is also notable for a surprising cast featuring ‘Bride of Frankenstein’ Elsa Lanchester in one of her last roles, alongside Ernest Borgnine as the execrable boss. There’s enough here to entertain and some material which can surprise. Well, you can now own this ratsploitation double bill in an attractive limited edition Blu-Ray box set: the good folk at Second Sight are about to release this, and you can find out more about it

Truth be told, neither Willard nor Ben are superb films and Ben is the weaker, but they’re certainly quite unlike anything else, and they have had some influence elsewhere. Willard even got a fairly glossy remake/’reimagining’ in the Noughties featuring cult actor Crispin Hellion Glover, so its reach was definitely there. Willard, in particular, is also notable for a surprising cast featuring ‘Bride of Frankenstein’ Elsa Lanchester in one of her last roles, alongside Ernest Borgnine as the execrable boss. There’s enough here to entertain and some material which can surprise. Well, you can now own this ratsploitation double bill in an attractive limited edition Blu-Ray box set: the good folk at Second Sight are about to release this, and you can find out more about it  Rather than a straightforward stand-alone short film, Empire of Dirt is intended to introduce characters and themes which will be explored fully in a feature-length offering. As such, no time is wasted: we’re shown, briefly, that these events are taking place in Manilla, 1997, and then we’re straight in to a frantic shootout, followed by a skirmish in a dilapidated building. It seems as though our protagonist is coming to the aid of a desperate, terrified woman, at least on first impressions: whatever his loyalty to her is, he pitches himself into some gritty, bloody and physical action, killing those he finds, with the violence happening both on and off screen. It’s a testament to Mason’s directorial abilities here that, even in a few short minutes, you feel as disturbed by the violence taking place off-screen as you do the violence in front of you.

Rather than a straightforward stand-alone short film, Empire of Dirt is intended to introduce characters and themes which will be explored fully in a feature-length offering. As such, no time is wasted: we’re shown, briefly, that these events are taking place in Manilla, 1997, and then we’re straight in to a frantic shootout, followed by a skirmish in a dilapidated building. It seems as though our protagonist is coming to the aid of a desperate, terrified woman, at least on first impressions: whatever his loyalty to her is, he pitches himself into some gritty, bloody and physical action, killing those he finds, with the violence happening both on and off screen. It’s a testament to Mason’s directorial abilities here that, even in a few short minutes, you feel as disturbed by the violence taking place off-screen as you do the violence in front of you. Few writers have had their work adapted for the screen half so much as Stephen King, nor with such variable results, but then this is exactly to be expected when the man himself’s work has varied so wildly over the years. When it comes to the huge tomes from his early days, such as The Stand and IT, the TV miniseries has often seemed to be the way to go, rather than making a feature film. Particularly bearing in mind that epic-length films are really more a contemporary domain, it no doubt made sense, even if for manageability alone, to serialise the events of the books over a period of weeks. The resulting TV version of IT, made in 1990, for all its (now apparent) flaws cemented itself as a formative experience for many viewers, particularly those of us in our thirties. Look at it now, and what you mainly see are the awkward birth pangs of CGI; back then, though, everyone – very few of whom had read the book, and many of whom were children themselves – were frightened of Pennywise the Clown.

Few writers have had their work adapted for the screen half so much as Stephen King, nor with such variable results, but then this is exactly to be expected when the man himself’s work has varied so wildly over the years. When it comes to the huge tomes from his early days, such as The Stand and IT, the TV miniseries has often seemed to be the way to go, rather than making a feature film. Particularly bearing in mind that epic-length films are really more a contemporary domain, it no doubt made sense, even if for manageability alone, to serialise the events of the books over a period of weeks. The resulting TV version of IT, made in 1990, for all its (now apparent) flaws cemented itself as a formative experience for many viewers, particularly those of us in our thirties. Look at it now, and what you mainly see are the awkward birth pangs of CGI; back then, though, everyone – very few of whom had read the book, and many of whom were children themselves – were frightened of Pennywise the Clown. IT also uses its now thirty-years-old setting, a world before health and safety, safeguarding and more concerted efforts to tackle bullying, to present childhood itself as horrific. Sure, these kids didn’t have to prefix ‘bullying’ with ‘cyber’, but no one was tranquilised by mobile phones and social media, either: it plain didn’t exist. Your plight was your own, and your world ended at the edge of town, or went as far as your friendship group – if you had one. It seems to me that knowing all of this – seeing these changes – has also been used to add to the impact of the supernatural horror. (This would have been as much the case had they left the setting in the mid-twentieth century, mind, but fewer of us would now recognise that in the same degree of detail.) As for the adults in IT, and bearing in mind that many viewers are now approximately the same age as them and not the kids, they’re represented as negligent at best, incestuous at worst: they cajole, they medicate, they exploit but most of all, they ignore their offspring completely. Their children are ripe pickings for any sinister force which might come along.

IT also uses its now thirty-years-old setting, a world before health and safety, safeguarding and more concerted efforts to tackle bullying, to present childhood itself as horrific. Sure, these kids didn’t have to prefix ‘bullying’ with ‘cyber’, but no one was tranquilised by mobile phones and social media, either: it plain didn’t exist. Your plight was your own, and your world ended at the edge of town, or went as far as your friendship group – if you had one. It seems to me that knowing all of this – seeing these changes – has also been used to add to the impact of the supernatural horror. (This would have been as much the case had they left the setting in the mid-twentieth century, mind, but fewer of us would now recognise that in the same degree of detail.) As for the adults in IT, and bearing in mind that many viewers are now approximately the same age as them and not the kids, they’re represented as negligent at best, incestuous at worst: they cajole, they medicate, they exploit but most of all, they ignore their offspring completely. Their children are ripe pickings for any sinister force which might come along. Festival season is upon us once more, and one by one, the best horror and genre film festivals of the UK are revealing what they have lined up. Myself and co-editor Ben often take ourselves down to Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema for Celluloid Screams: now in its ninth year, it has introduced us to a range of excellent films during the years we’ve been attending, and films we see there have often wound up on our ‘Best Of’ lists at the end of the year – proving that festivals are where it’s at for film fans. This year looks to be no different, with an absolutely stellar line-up coming our way. Whilst there’s often a bit of overlap between festivals of this nature (no bad thing, in my opinion, meaning that most people will be able to get to at least one of the screenings they’re after) Celluloid Screams has also got the steal on some intriguing and exciting new films.

Festival season is upon us once more, and one by one, the best horror and genre film festivals of the UK are revealing what they have lined up. Myself and co-editor Ben often take ourselves down to Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema for Celluloid Screams: now in its ninth year, it has introduced us to a range of excellent films during the years we’ve been attending, and films we see there have often wound up on our ‘Best Of’ lists at the end of the year – proving that festivals are where it’s at for film fans. This year looks to be no different, with an absolutely stellar line-up coming our way. Whilst there’s often a bit of overlap between festivals of this nature (no bad thing, in my opinion, meaning that most people will be able to get to at least one of the screenings they’re after) Celluloid Screams has also got the steal on some intriguing and exciting new films.