More and more these days, we’re seeing academic studies of what is often regarded as genre cinema; this ties in with the rise and rise of film studies more generally, with horror finally being regularly recognised and brought into the fold. In the past few months alone, for instance, I’ve reviewed books on The Shining, Don’t Look Now, A Company of Wolves and The Grudge. Given the origins of some of the films now receiving this treatment, you can only imagine just how far this new scholarly interest must be from anything the filmmakers ever imagined at the time, and where I Spit on Your Grave director Meir Zarchi is concerned, his film’s journey from execrable to esteemed has taken a very steep arc. Still, at their best these kinds of focused cinematic studies can successfully contextualise and hopefully interrogate notorious movies – which was my hope for David Maguire’s monograph on Zarchi’s 1978 film (hereafter known as ISOYG). As an additional tester, and one of the reasons I requested a review copy of the book, I’m by no means a fan of ISOYG; I was interested to see if the book would address any of the issues I have with the film overall and/or bring me around to its merits. Happily, this is the case.

More and more these days, we’re seeing academic studies of what is often regarded as genre cinema; this ties in with the rise and rise of film studies more generally, with horror finally being regularly recognised and brought into the fold. In the past few months alone, for instance, I’ve reviewed books on The Shining, Don’t Look Now, A Company of Wolves and The Grudge. Given the origins of some of the films now receiving this treatment, you can only imagine just how far this new scholarly interest must be from anything the filmmakers ever imagined at the time, and where I Spit on Your Grave director Meir Zarchi is concerned, his film’s journey from execrable to esteemed has taken a very steep arc. Still, at their best these kinds of focused cinematic studies can successfully contextualise and hopefully interrogate notorious movies – which was my hope for David Maguire’s monograph on Zarchi’s 1978 film (hereafter known as ISOYG). As an additional tester, and one of the reasons I requested a review copy of the book, I’m by no means a fan of ISOYG; I was interested to see if the book would address any of the issues I have with the film overall and/or bring me around to its merits. Happily, this is the case.

A slim volume of 140 pages altogether (including notes, filmography and bibliography), the book starts very promisingly. Making a firm case for the film’s uniqueness and the ‘pared down’ qualities which have been embellished (read: spoiled) in most of the subsequent entrants into the rape/revenge canon, Maguire then gets into the relevant history of 1970s and 80s America. The US at the time was immersed in significant changes to legislature and social movements impacting upon women’s rights, which can be seen to have led to male anxieties in response to their own shifting, jeopardised roles, which culminated in backlash. In this section, Maguire suggests that this spirit of backlash found expression in contemporary cinema; I’d agree with some of the examples he offers, but not with others (the human ‘meat’ in Texas Chainsaw Massacre does not for me represent anything significant about women, and conflating it with the infamous Hustler Magazine ‘meat’ cover doesn’t follow for me). Still, a rundown of the films which were released very close in time to ISOYG does indeed demonstrate that there was a cinematic seam of subjugated and abused women, which is interesting context.

Maguire then documents the history of the making of and release of ISOYG; happily, he pulls no punches here, noting the large disconnect between Zarchi’s professed noble intentions and the marketing of the film itself (though noting that bad publicity is still publicity, with the likes of Roger Ebert and the BBFC cementing the film’s reputation in ways which neither Zarchi nor Jerry Gross could have ever done. Oh, and whilst detailing the film’s retitling and releases in other countries, Maguire gives us the fun fact that in Ecuador ISOYG was renamed Suspiria 2: Killer Sharks, in a bold attempt to trade off both Argento’s original and the success of Jaws, and no doubt leading to many confused and disappointed viewers.

The debate set up in the chapter entitled ‘Filth or Feminism?’ covers engaging analysis of the film, balancing description of its defiantly non-salacious scenes against, again refreshingly, questions about Zarchi’s professed motivations and decision-making. For example, why did he say that Camille Keaton’s “slim delicate figure and […] soft ethereal beauty” made her so suitable for the character of Jennifer Hills? Maguire notes that rape/revenge films still opt for young, beautiful female characters, so it’s a valid concern here. Maguire also interrogates Zarchi’s claims of naivety over how the film would be received, given that he had courted controversy before.

In looking at the wealth of critical response between 1978 and the present, I was actually pleased to read about how Stephen R. Monroe (director of the first ISOYG remake) took issues with a key plot element in the original; that is, how a gang-raped woman uses consensual sex as part of her vengeance. That, far more than the notorious 25 minute attack scene, is the one which has always given me conniptions; having announced my bias, I’ll say that this section of the book is probably the most frank and revealing for me. Where Maguire reaches further, citing influences from mythology on the characters, setting and themes of ISOYG, I confess to being curious rather than wholly convinced – but then again, some of the women in rape/revenge films seem to acquire quasi-supernatural powers before they seek their revenge, which is itself every bit as unrealistic as Keaton’s Jennifer Hills going on her seduction drive in the original film.

The book follows with exhaustive research into the legacy of ISOYG. There are some genuine surprises here as Maguire identifies a number of very thematically similar films which have emerged since the ‘Ground Zero’ of the genre got its release (including a spoof?!) and then there’s a good long look at the merits and demerits of the remake/subsequent-to-the-remake films, which can be seen as a franchise. He’s very fair, offers a number of well-argued points in defence of ISOYG (2010) and goes some way to dispel what has turned into a dichotomy between original and remake: first film good, remake bad. He is, though, far less kind to the 2013 sequel, a film I cannot comment on as I avoided it like the plague…

The book follows with exhaustive research into the legacy of ISOYG. There are some genuine surprises here as Maguire identifies a number of very thematically similar films which have emerged since the ‘Ground Zero’ of the genre got its release (including a spoof?!) and then there’s a good long look at the merits and demerits of the remake/subsequent-to-the-remake films, which can be seen as a franchise. He’s very fair, offers a number of well-argued points in defence of ISOYG (2010) and goes some way to dispel what has turned into a dichotomy between original and remake: first film good, remake bad. He is, though, far less kind to the 2013 sequel, a film I cannot comment on as I avoided it like the plague…

As a worst-case scenario, this book could have been a very dry, very pompous meta-analysis of ISOYG which used lots of words to say little. Instead, I’ve been very pleasantly surprised. Maguire comes across as bright and personable, clever and focused without ever wallowing in jargon, and perhaps most importantly of all, aware that ISOYG is not a perfect film whilst still eminently worth of a closer look. A well-written piece of work, the book could easily reward fans as much as students and it’s well worth a place on the shelf. Now, we wait to see if Zarchi’s long-awaited official sequel to ISOYG actually does land this year…

I Spit on Your Grave by David Maguire is available now as part of the ‘Cultographies’ series from Wallflower Press.

A few years ago, the site (in its old incarnation) was approached with an indie film which looked decidedly different to most films we receive; this turned out to be abundantly and delightfully the case. Whilst we do get a fair range of styles and genres,

A few years ago, the site (in its old incarnation) was approached with an indie film which looked decidedly different to most films we receive; this turned out to be abundantly and delightfully the case. Whilst we do get a fair range of styles and genres,  While I embraced Rollin instantly, getting into Franco took a while longer. I can’t quite remember which my very first Jess Franco experience was. It was around the same time as Jean Rollin, again on pirate VHS. It may have been Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula (1998), or Cannibals(1980) with Al Cliver. Neither one is an easy film for a newcomer! It took me some three-four years of frustration to ‘get’ Franco’s cinema. I really started appreciating and obsessing over his work after having seen Exorcism (1974) and Eugenie De Sade (1971) with Soledad Miranda. These films have resonated with me, and have also prompted me to try my hand at more erotic themes. I’ve had the idea of making a film along the lines of Eugenie de Sade for a number of years. I got the opportunity to make that happen in 2016 with S&M: Les Sadiques. My original screenplay was even more closely modelled on Franco’s film, but got altered down the road due to budget restrictions. So yes, my films are very influenced by Rollin and Franco.

While I embraced Rollin instantly, getting into Franco took a while longer. I can’t quite remember which my very first Jess Franco experience was. It was around the same time as Jean Rollin, again on pirate VHS. It may have been Mari-Cookie and the Killer Tarantula (1998), or Cannibals(1980) with Al Cliver. Neither one is an easy film for a newcomer! It took me some three-four years of frustration to ‘get’ Franco’s cinema. I really started appreciating and obsessing over his work after having seen Exorcism (1974) and Eugenie De Sade (1971) with Soledad Miranda. These films have resonated with me, and have also prompted me to try my hand at more erotic themes. I’ve had the idea of making a film along the lines of Eugenie de Sade for a number of years. I got the opportunity to make that happen in 2016 with S&M: Les Sadiques. My original screenplay was even more closely modelled on Franco’s film, but got altered down the road due to budget restrictions. So yes, my films are very influenced by Rollin and Franco. AB: Yes, it’s been a deliberate tactic on my part. Many potentially amazing films have been ruined due to female characters being represented as not having a will of their own, subordinate to males. No amount of beautiful editing or plot twists can atone for that. So in my own work I’m going in the opposite direction, with often un-heroic males and bold, superior females. As for r

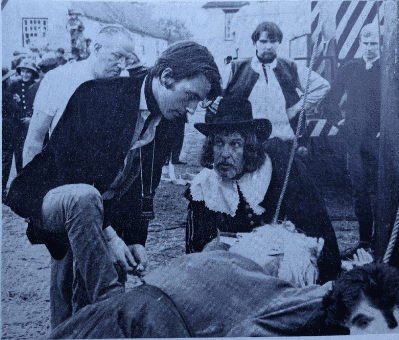

AB: Yes, it’s been a deliberate tactic on my part. Many potentially amazing films have been ruined due to female characters being represented as not having a will of their own, subordinate to males. No amount of beautiful editing or plot twists can atone for that. So in my own work I’m going in the opposite direction, with often un-heroic males and bold, superior females. As for r Times of great uncertainty and bloodshed have always seemed to bolster paranoia and irrational thought. Change offers to dispose of the unconscionable practices of the past, but even as old beliefs and practices are on the verge of being swept away, people still to seek them out, retreating into watchful suggestibility any time the pace of change progresses too quickly. You might like to name any number of examples from history, but in terms of the English Civil War – which provides our context here – a countrywide dispute over governance, supported by new warfare and weaponry, continued to cast a long shadow, and people did not simply forget what had gone before; far from it. Suspicions over one’s neighbours were still framed by supernatural suspicions, or at least framed in compelling supernatural language; in a similar way to today, where people gloss over the complex, uncomfortable truths to look instead for clues about conspiracies, the people of the mid-17th Century accused one another of witchcraft. Discerning opportunists, like the ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins, were all too willing to exploit this.

Times of great uncertainty and bloodshed have always seemed to bolster paranoia and irrational thought. Change offers to dispose of the unconscionable practices of the past, but even as old beliefs and practices are on the verge of being swept away, people still to seek them out, retreating into watchful suggestibility any time the pace of change progresses too quickly. You might like to name any number of examples from history, but in terms of the English Civil War – which provides our context here – a countrywide dispute over governance, supported by new warfare and weaponry, continued to cast a long shadow, and people did not simply forget what had gone before; far from it. Suspicions over one’s neighbours were still framed by supernatural suspicions, or at least framed in compelling supernatural language; in a similar way to today, where people gloss over the complex, uncomfortable truths to look instead for clues about conspiracies, the people of the mid-17th Century accused one another of witchcraft. Discerning opportunists, like the ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins, were all too willing to exploit this. The troubled making of the film is as notorious as the events of the film itself, and much has been made of Michael Reeves’ fury at the studio pressure which forced him to cast Vincent Price in his lead role. It’s well-documented that he was rude and dismissive of Price, whilst Price remembered the experience of making Witchfinder General as the only time he ever really clashed with a director. I can see why Reeves was wary of casting Price, as he was hardly known for the type of film which the younger man was setting out to make, though some of the heated exchanges between them are hardly defensible – but Price’s acknowledged disillusionment with the film lends him a miserable gravitas in-role which is note-perfect. Many of the film’s sinister attributes come directly from Vincent Price’s performance, although the supporting cast are superb. I also feel that the casting of a much older man than the real Hopkins would have been works to the film’s advantage. Price is able to bring a rather jaded, menacing presence to the film, and he acts as a perfect foil for Ogilvy, the young career soldier. The two men are the embodiment of the old and the new, and on screen, the effect is mesmerising. Price himself, once safely back in the California sunshine, was able to acknowledge that Witchfinder General’s troubled birth had in fact led to one of his best-ever performances, and, ever the gentleman, he wrote to Reeves to say so.

The troubled making of the film is as notorious as the events of the film itself, and much has been made of Michael Reeves’ fury at the studio pressure which forced him to cast Vincent Price in his lead role. It’s well-documented that he was rude and dismissive of Price, whilst Price remembered the experience of making Witchfinder General as the only time he ever really clashed with a director. I can see why Reeves was wary of casting Price, as he was hardly known for the type of film which the younger man was setting out to make, though some of the heated exchanges between them are hardly defensible – but Price’s acknowledged disillusionment with the film lends him a miserable gravitas in-role which is note-perfect. Many of the film’s sinister attributes come directly from Vincent Price’s performance, although the supporting cast are superb. I also feel that the casting of a much older man than the real Hopkins would have been works to the film’s advantage. Price is able to bring a rather jaded, menacing presence to the film, and he acts as a perfect foil for Ogilvy, the young career soldier. The two men are the embodiment of the old and the new, and on screen, the effect is mesmerising. Price himself, once safely back in the California sunshine, was able to acknowledge that Witchfinder General’s troubled birth had in fact led to one of his best-ever performances, and, ever the gentleman, he wrote to Reeves to say so. In terms of an English cinematic legacy, Witchfinder General has come to be widely-credited for its influence on what’s now broadly referred to as ‘folk horror’: this is a very broad church overall, but one which often derives its terrors from landscape, seclusion and the pesky resurgence of old gods. Whilst Witchfinder General’s relationship with the supernatural is rather minimal, positioning its witchcraft as a bludgeoning tool of exploitation and repression used by the powerful, its trials and burnings take place in a rural 17th century setting which seems primed for sinister events, offering contrast and incongruity whilst exploring a period in time when fervent Christian belief was meant to be at its apex. If the society of Witchfinder General needlessly burned its witches, then Blood on Satan’s Claw, with its slightly later setting, goes a step further by ploughing up a real devil for people to worship. The thread of sinister communities and historical unreason started in 1968, travelled to Europe in films such as Mark of the Devil, and in the years since, a resurgent interest in these folk horrors has led to modern-day films like A Field in England (2013), also set during the English Civil War. Its characters could almost be contemporary with the characters in Michael Reeves’ film.

In terms of an English cinematic legacy, Witchfinder General has come to be widely-credited for its influence on what’s now broadly referred to as ‘folk horror’: this is a very broad church overall, but one which often derives its terrors from landscape, seclusion and the pesky resurgence of old gods. Whilst Witchfinder General’s relationship with the supernatural is rather minimal, positioning its witchcraft as a bludgeoning tool of exploitation and repression used by the powerful, its trials and burnings take place in a rural 17th century setting which seems primed for sinister events, offering contrast and incongruity whilst exploring a period in time when fervent Christian belief was meant to be at its apex. If the society of Witchfinder General needlessly burned its witches, then Blood on Satan’s Claw, with its slightly later setting, goes a step further by ploughing up a real devil for people to worship. The thread of sinister communities and historical unreason started in 1968, travelled to Europe in films such as Mark of the Devil, and in the years since, a resurgent interest in these folk horrors has led to modern-day films like A Field in England (2013), also set during the English Civil War. Its characters could almost be contemporary with the characters in Michael Reeves’ film. Whatever the situation was immediately following its release, no single horror film in history seems to have attracted such a proliferating amount of critical commentary as The Shining. And, few films have lent themselves to so much of what many lay viewers would see as frankly barmy analysis; okay, if you’ve ever watched a certain documentary called Room 237, then you’ll know exactly what I mean, and afterwards you might have felt less that you’ve been asked to consider various ‘explanations’ of the film and more that you’ve been up close and personal with delusion. Still, The Shining is a film which can withstand a certain amount of this kind of thing, and if it can sustain being reinterpreted as a metaphor about the Greek myth of the labyrinth with Jack as the Minotaur, then it can handle being critically reinterpreted in a broader sense, as part of the ongoing Devil’s Advocates series. I’ve reviewed several of these titles before: overall, these books strike a good, readable balance between academia and general interest, albeit that academic studies often tread some familiar paths in their analyses. Here, author Laura Mee is up for the task of assessing and discussing this landmark horror film, though one which has often been seen as a cold imposter to the genre, and remains a contested piece of work.

Whatever the situation was immediately following its release, no single horror film in history seems to have attracted such a proliferating amount of critical commentary as The Shining. And, few films have lent themselves to so much of what many lay viewers would see as frankly barmy analysis; okay, if you’ve ever watched a certain documentary called Room 237, then you’ll know exactly what I mean, and afterwards you might have felt less that you’ve been asked to consider various ‘explanations’ of the film and more that you’ve been up close and personal with delusion. Still, The Shining is a film which can withstand a certain amount of this kind of thing, and if it can sustain being reinterpreted as a metaphor about the Greek myth of the labyrinth with Jack as the Minotaur, then it can handle being critically reinterpreted in a broader sense, as part of the ongoing Devil’s Advocates series. I’ve reviewed several of these titles before: overall, these books strike a good, readable balance between academia and general interest, albeit that academic studies often tread some familiar paths in their analyses. Here, author Laura Mee is up for the task of assessing and discussing this landmark horror film, though one which has often been seen as a cold imposter to the genre, and remains a contested piece of work. Not only does Mee debunk a lot of King’s strident criticisms of the film by offering recorded evidence which suggests that he, at least initially, really liked the film, but she goes deeper than this and makes an excellent case for judging an adaptation as far as possible on its own merits, rather than seeing it as ‘too different’ from the source material. There’s a fascinating section on what was left out between novel and screenplay and why, with supporting material from Kubrick’s own notebooks. It also seems relevant to note that Kubrick was not the first nor the last to omit or limit King’s more insalubrious sexual content from his screenplay, and for good reason: IT (2017) also springs to mind here. Ultimately, the films are not the books, and it is successfully argued here that transformative decisions are made for good reasons.

Not only does Mee debunk a lot of King’s strident criticisms of the film by offering recorded evidence which suggests that he, at least initially, really liked the film, but she goes deeper than this and makes an excellent case for judging an adaptation as far as possible on its own merits, rather than seeing it as ‘too different’ from the source material. There’s a fascinating section on what was left out between novel and screenplay and why, with supporting material from Kubrick’s own notebooks. It also seems relevant to note that Kubrick was not the first nor the last to omit or limit King’s more insalubrious sexual content from his screenplay, and for good reason: IT (2017) also springs to mind here. Ultimately, the films are not the books, and it is successfully argued here that transformative decisions are made for good reasons. We receive quite a lot of short films overall at the site, and it’s always fun seeing what kind of a calling-card filmmakers have on offer: better still is when films channel formative horror and nostalgia along the way, which is the case with She Came From The Woods (2017).

We receive quite a lot of short films overall at the site, and it’s always fun seeing what kind of a calling-card filmmakers have on offer: better still is when films channel formative horror and nostalgia along the way, which is the case with She Came From The Woods (2017). WP: Is the film and its mythos intended to stay a short, or is the story-line one you’d like to revisit at any point in future? I have to say, it feels like it could be expanded into a longer story…

WP: Is the film and its mythos intended to stay a short, or is the story-line one you’d like to revisit at any point in future? I have to say, it feels like it could be expanded into a longer story… It’s a very rare thing indeed to see a filmmaker working in the styles so far chosen by director Alex Bakshaev in his career to date. His last film, The Devil of Kreuzberg, was to my mind a languid and stylish love letter to Jean Rollin; in S&M, Les Sadiques, we have a film not only openly dedicated to Jess Franco, but one clearly taking its visual cues from Uncle Jess – and on a budget of a mere 250 Euros, working within the confines of a budget which would startle even Franco. However, in common with The Devil of Kreuzberg, there’s so much evident love for source material which doesn’t tend to hold much sway over modern filmmakers, that it’s impossible not to be impressed and to an extent, entranced by the results.

It’s a very rare thing indeed to see a filmmaker working in the styles so far chosen by director Alex Bakshaev in his career to date. His last film, The Devil of Kreuzberg, was to my mind a languid and stylish love letter to Jean Rollin; in S&M, Les Sadiques, we have a film not only openly dedicated to Jess Franco, but one clearly taking its visual cues from Uncle Jess – and on a budget of a mere 250 Euros, working within the confines of a budget which would startle even Franco. However, in common with The Devil of Kreuzberg, there’s so much evident love for source material which doesn’t tend to hold much sway over modern filmmakers, that it’s impossible not to be impressed and to an extent, entranced by the results. But as much as Jess Franco – and de Sade – are acknowledged influences on S&M: Les Sadiques, the overall style of the film is less uproarious than many a Jess Franco film, generally preferring atmosphere over action, and developing said atmosphere in meticulous ways. Whilst a sexual film in terms of its themes, the director is very selective about what is shown, though without shying away from nudity and encompassing one quite startling and brutal scene, too. The topics of control and consent are de facto explored here, though is a subtle array of ways. There is, again, a touch of magic in how Bakshaev manages to shoot Berlin, making the city look by turns very modern and recognisable, but then timeless, expressed through a series of interesting shots. The atmosphere also owes a great deal to the film’s minimal dialogue – sometimes we do not hear what characters are saying at all as they are not miked – and exposition. We simply accept Sandra and Marie’s relationship grows seemingly out of nowhere, for instance, because it just works that way, and it’s plausible within the confines of the film’s universe. The camera lingers on facial expressions and gestures in a very effective way too, adding to the pleasingly disorientating effect of the filming style overall. This is altogether quieter than the films which have inspired Les Sadiques, but genuinely works well and showcases a confident, ambitious set of attitudes to making cinema. A special mention has to go to Sandra Bourdonnec here, too, who is joined by a great cast but whose magnetism is quite unlike anything else on the screen: the star of The Devil of Kreuzberg exudes the kind of smouldering appeal which would not look amiss in any of the classic Euro horror or arthouse cinema we know and love.

But as much as Jess Franco – and de Sade – are acknowledged influences on S&M: Les Sadiques, the overall style of the film is less uproarious than many a Jess Franco film, generally preferring atmosphere over action, and developing said atmosphere in meticulous ways. Whilst a sexual film in terms of its themes, the director is very selective about what is shown, though without shying away from nudity and encompassing one quite startling and brutal scene, too. The topics of control and consent are de facto explored here, though is a subtle array of ways. There is, again, a touch of magic in how Bakshaev manages to shoot Berlin, making the city look by turns very modern and recognisable, but then timeless, expressed through a series of interesting shots. The atmosphere also owes a great deal to the film’s minimal dialogue – sometimes we do not hear what characters are saying at all as they are not miked – and exposition. We simply accept Sandra and Marie’s relationship grows seemingly out of nowhere, for instance, because it just works that way, and it’s plausible within the confines of the film’s universe. The camera lingers on facial expressions and gestures in a very effective way too, adding to the pleasingly disorientating effect of the filming style overall. This is altogether quieter than the films which have inspired Les Sadiques, but genuinely works well and showcases a confident, ambitious set of attitudes to making cinema. A special mention has to go to Sandra Bourdonnec here, too, who is joined by a great cast but whose magnetism is quite unlike anything else on the screen: the star of The Devil of Kreuzberg exudes the kind of smouldering appeal which would not look amiss in any of the classic Euro horror or arthouse cinema we know and love. Rumours of an Evil Dead IV have been turning up reliably every few years, but nothing concrete has ever really come along to substantiate these. Personally, I feel like it was an either/or thing with the Evil Dead remake in 2013 – and we ended up with the remake, which aside from that (rather head-scratching) Bruce Campbell cameo after the end credits, moved things in a different direction, even though it ostensibly used the same mythology. Gone was the splatstick and the one-liners which we’d left off with after Evil Dead III; we were back with an altogether grislier spin which dispensed with the comedy altogether. If this was to be our last encounter with the Necronomicon, then we’d be ending on a very different note to what we’d come to expect from Raimi and Campbell – which sat a little awkwardly with many people, myself included.

Rumours of an Evil Dead IV have been turning up reliably every few years, but nothing concrete has ever really come along to substantiate these. Personally, I feel like it was an either/or thing with the Evil Dead remake in 2013 – and we ended up with the remake, which aside from that (rather head-scratching) Bruce Campbell cameo after the end credits, moved things in a different direction, even though it ostensibly used the same mythology. Gone was the splatstick and the one-liners which we’d left off with after Evil Dead III; we were back with an altogether grislier spin which dispensed with the comedy altogether. If this was to be our last encounter with the Necronomicon, then we’d be ending on a very different note to what we’d come to expect from Raimi and Campbell – which sat a little awkwardly with many people, myself included. So with all of that said, how come I’m not howling with indignation at the show’s cancellation? Well, part of me is, absolutely, as the tyranny of ‘viewing figures’ is only a limited measure of how a show is doing, really, if you could only wait and see. Movies which sink at the Box Office often rejuvenate on DVD and merchandise sales. But it seems pretty impossible that my indignation here would achieve anything, and now that Bruce himself has closed the door, we would be better off accepting that we’re done here. And, whilst I have confidence in Sam and Ivan Raimi – alongside the rest of the talented writers they’ve worked with on the show – you never know what market forces and other factors can throw at you; a potential universe where we’re on Series Ten and the well is running dry sounds pretty unappealing, even if not quite ‘Dark Ones walking the earth’ unappealing. The worst case scenario is a horror version of The Big Bang Theory, which at least we’re definitely being spared.

So with all of that said, how come I’m not howling with indignation at the show’s cancellation? Well, part of me is, absolutely, as the tyranny of ‘viewing figures’ is only a limited measure of how a show is doing, really, if you could only wait and see. Movies which sink at the Box Office often rejuvenate on DVD and merchandise sales. But it seems pretty impossible that my indignation here would achieve anything, and now that Bruce himself has closed the door, we would be better off accepting that we’re done here. And, whilst I have confidence in Sam and Ivan Raimi – alongside the rest of the talented writers they’ve worked with on the show – you never know what market forces and other factors can throw at you; a potential universe where we’re on Series Ten and the well is running dry sounds pretty unappealing, even if not quite ‘Dark Ones walking the earth’ unappealing. The worst case scenario is a horror version of The Big Bang Theory, which at least we’re definitely being spared. My influences come straight from my emotions. I always start creatively with an emotion or tone I want to convey before exploring a narrative. I am drawn to all sorts of storylines and themes, but they key for me is to tell them with a sense of romantic optimism. Sundown could easily have been a depressing and stark social realistic arthouse film, but I want to inspire audiences, make them feel a range of emotions.

My influences come straight from my emotions. I always start creatively with an emotion or tone I want to convey before exploring a narrative. I am drawn to all sorts of storylines and themes, but they key for me is to tell them with a sense of romantic optimism. Sundown could easily have been a depressing and stark social realistic arthouse film, but I want to inspire audiences, make them feel a range of emotions.

“Where do the ideas come from?” It’s a standard question which, for many people working in the creative industries, there’s probably never a standard answer; however, in the new indie movie A Brilliant Monster, the trials and tribulations of continually coming up with workable new projects is given a dark, original twist. It’s an original idea about getting original ideas, if you will.

“Where do the ideas come from?” It’s a standard question which, for many people working in the creative industries, there’s probably never a standard answer; however, in the new indie movie A Brilliant Monster, the trials and tribulations of continually coming up with workable new projects is given a dark, original twist. It’s an original idea about getting original ideas, if you will. This behaviour is refracted through an earthy, plausible script which generally works very well – a definite plus, given that this film really lives or dies by its dialogue. On occasion, the repetitive “where do you get the ideas?” line coming from different players can be a little excessive – A Brilliant Monster is capable of establishing its themes beyond doubt without this repetition – but otherwise, the script is good at balancing its touches of humour against moving the narrative forwards. Along the way, it asks some interesting questions and raises some interesting points. For example, the film shows how someone’s celebrity status can impair our judgement of them: the first cop on the case cannot really believe that a famous author could behave in a criminal way, later characters feel just the same way regardless of their backgrounds, and this certainty that status = irreproachable conduct is toyed with throughout the film. People are just seduced by Mitch’s fame; they can’t really see any further. But perhaps more tellingly, A Brilliant Monster looks at the grotesque side of the creative process: in this process, women seem to fare particularly badly (a grisly literal riff on the idea of the ‘muse’ maybe) but as the stakes get higher, Mitch is forced to make ever more difficult tactical decisions in return for what he needs as a writer. The relationship between him, his past, his purpose in writing and his inspiration are given an engaging treatment here.

This behaviour is refracted through an earthy, plausible script which generally works very well – a definite plus, given that this film really lives or dies by its dialogue. On occasion, the repetitive “where do you get the ideas?” line coming from different players can be a little excessive – A Brilliant Monster is capable of establishing its themes beyond doubt without this repetition – but otherwise, the script is good at balancing its touches of humour against moving the narrative forwards. Along the way, it asks some interesting questions and raises some interesting points. For example, the film shows how someone’s celebrity status can impair our judgement of them: the first cop on the case cannot really believe that a famous author could behave in a criminal way, later characters feel just the same way regardless of their backgrounds, and this certainty that status = irreproachable conduct is toyed with throughout the film. People are just seduced by Mitch’s fame; they can’t really see any further. But perhaps more tellingly, A Brilliant Monster looks at the grotesque side of the creative process: in this process, women seem to fare particularly badly (a grisly literal riff on the idea of the ‘muse’ maybe) but as the stakes get higher, Mitch is forced to make ever more difficult tactical decisions in return for what he needs as a writer. The relationship between him, his past, his purpose in writing and his inspiration are given an engaging treatment here.