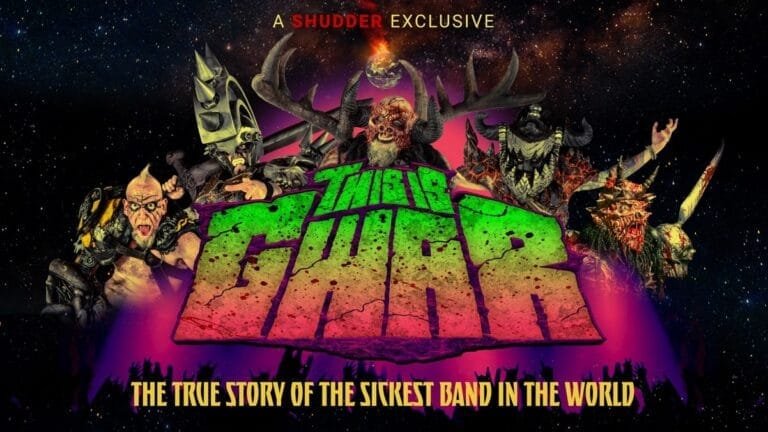

There has been a minor run of punk and metal documentary-making in recent years: some of these do a fine job of simply retelling an interesting band history, and some go a step further, telling us more about what it means to be in a certain band or to have lived through a certain time period. This is Gwar (2021) is in the latter camp, and it’s one of the best examples of these documentaries. Sure, it follows the standard trajectory of the rise, the fall, the comeback – and it’s plotted fairly linearly by album releases, once it explains how Gwar came to be in the first place. But along the way, it turns out to be a really engaging time capsule, all about a brief window of opportunity which was taken up by a few enterprising individuals: it’s a coming together of art, punk, comics, filmmaking and music which it feels really difficult to imagine happening now. You don’t need to be a huge Gwar fan to appreciate this; huge Gwar fans should, of course, pick this up, as there’s little need or likelihood of another film like this one, but if you’re in any way a music fan wondering how the stars seemed to align on certain highly improbable projects, then look no further.

Because let’s be honest: Gwar is a highly improbable project which has just been going long enough for us all to get used to it. Even within the realms of metal, which has never been averse to a grisly stage show or lacking the propensity to shock, Gwar made a name for themselves by always going that bit further. It still feels hard to place them, but for the uninitiated – imagine the most grisly Grand Guignol moments of Alice Cooper’s old stage shows, and cross it with Peter Jackson’s early filmmaking career – think Bad Taste in particular. It’s rock music, it has a sense of demented spectacle, and it’s overlaid with a narrative about how the band are in fact interplanetary aliens, stuck on a lousy planet – yes, this one – which they hate (so rather like Jackson’s aliens, again, even if Gwar are better partially-dressed). The film opens with one of the band’s crew, tasked with prepping the tanks and hoses for a live show: he explains, with a wry smile on his face, all of the different mock bodily fluids that this kit will be expected to churn out. There you go – do something long enough, and it becomes normal. It’s a fitting place to start: but how did we get here?

The film moves into a potted history of 80s Richmond, VA, where there was a clash between a generally very conservative mainstream and the student art scene there – a kind of Reaganism vs subculture which was being played out everywhere at the time, but perhaps even more so in highly-traditionalist Virginia. From this burgeoning scene came a young man called Hunter Jackson, a student who loved horror, sci-fi, Dungeons & Dragons and making film props. As a talented drawer and painter, he wasn’t made welcome by his art lecturers, who disliked his ‘low-brow’ style (which is in the eye of the beholder, but sadly in this case the beholder was running the art classes). Hunter had been planning to make a film, working title Scumdogs of the Universe, which he then went ahead with as a big ‘fuck you’ to the sense of rejection he had felt; his film, of course, needed a cool soundtrack. Step forward, Dave Brockie, at the time heading up a performance-heavy punk outfit called Death Piggy; later, Death Piggy asked to borrow some of Jackson’s sci-fi gear to open for themselves, pretending to be a band called GWAR (which was just a guttural roar, a name which stuck). The band, and the back story, began to form into a whole, albeit in a rudimentary fashion at first.

A section of the film is given over to the burgeoning Gwar line-up, how the stage show grew, changed and grew again over the next couple of years, with some very entertaining (and on occasion, shocking) anecdotes about the ‘school bus’ touring days (a repurposed yellow school bus which the band gutted, and kitted out as highly uncomfortable, toilet-less sleeping quarters/prop transportation vehicle). Of course censorship was on its way – unsurprising, given the lyrics and the live show, though when the band eventually got hauled through the courts and answered to a judge called Dick Boner, it kind of made their next movie title, Phallus in Wonderland, sound tame by comparison. Maybe that’s how it got a Grammy nomination, and opened up a brief window to the mainstream: via Beavis & Butthead, Gwar wound up on The Joan Rivers Show, Jerry Springer and MTV News. It was perhaps at around this juncture – when the band was big enough to be known, in demand enough to be constantly on the road, but still small enough to do without security or any of the other trappings which could keep them safe – that they ended up being run off the road by would-be thieves who shot at them, hitting band member Peter Lee in the chest, puncturing his lung. Despite this near death experience, band members of the time note that they still went and took part in a This Toilet Earth promo shoot: by that point, a certain level of success was keeping them rolling, come what may.

It’s really at this point that, for this viewer, the film began to take on a different kind of significance. I’d even say – profound? As the band entered a far more tempestuous phase towards the late Nineties and early Noughties, with a run of resignations, personal issues, and of course deaths – a later incarnation of guitarist Flattus Maximus was found dead in the tour bus just before the band was due to cross the border into Canada – the band members left speaking about this now understandably change their tone. Sure, they reason, playing and performing was still fun, but the major shocks they endured either cemented, or damaged their friendships; things began to change, founding members began to peel off, and this triggered a lot of soul-searching about what was best to do. It’s a tale as old as time perhaps, but discussing the balance between success, reputation and living a life off the stage leads to some engaging content here, particularly from a band like Gwar. Gwar had, and has a life of its own which is a glorious thing, but also particularly difficult to separate from everything else. For the most part, the remaining members speak very warmly about their time in the band, but there’s a sense of the deepest sadness and regret about some aspects, particularly the death of wunderkind Dave ‘Oderus Urungus’ Brockie himself in 2014 – from an accidental heroin overdose, of all things. Sure, there’s some remnant bitterness too, but evidence of bridges being built now, and of course the band – now with no founding members left in it – keeps on going, with a new album out this year, thirty years down the line. Who saw that coming?

All in all, by the time the credits roll, you feel as though you’ve been privy to something at times deeply personal and moving – an odd sensation, given the film is about a band which has spent three decades bleeding, vomiting and ejaculating on their audiences. This is Gwar is funny, it’s entertaining, but it captures something else about what a rock band is and how it impacts on the people who perform in it. As bands change and popular entertainment shifts gear irrevocably, it definitely feels like we’ll not see the likes of Gwar again anytime soon, so I’d highly recommend this film: it’s a well-made, well-presented chance to be let in on the conversation about a very particular period in time.

The film is also peppered with the usual collection of early photos, flyers, backstage footage and promo material – all linked together by a comic strip, which illustrates the anecdotes being told – and some knowledgeable talking heads, from Weird Al to Brian Slagel. At nearly two hours long, that’s a lot of bloodied loin cloths, but quite honestly, the time flies by.

This is Gwar (2021) will be released on Shudder on July 21st, 2022.