The rise and rise of social media has definitively blurred the line between consent and content. Good horror films were quick to realise this, as horror so often is: by looking at the continual blurring of reality and unreality, persona and person, horror has invited us to think about a new, updating number of worst case scenarios. This brings us to Follow Her (2022), a brutal, succinct and fast-paced story about some very modern anxieties.

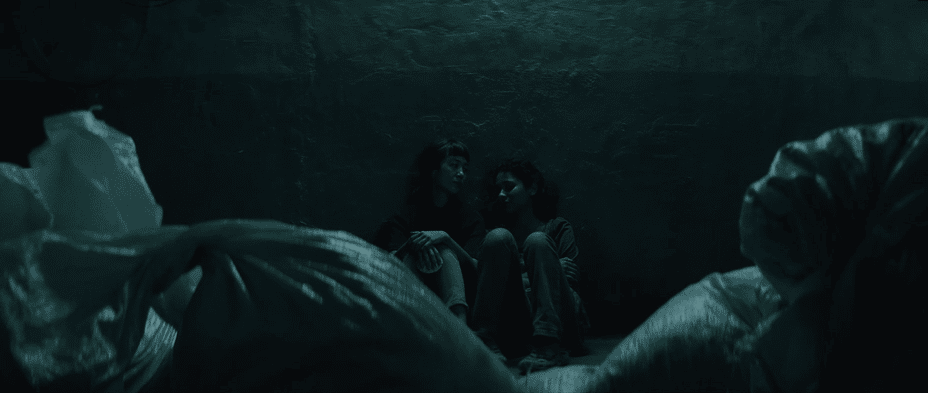

The film starts as it means to go on – by inviting the audience to ponder what we’re seeing, leading us one way and then another. There’s a guy in a box, see, being tormented by a woman (Dani Barker), but when her phone pings, she ends the session: ah, it’s a session. Jess, a social media influencer (and hopeful actress) who seems to live-stream everything she does – including, or perhaps especially locking guys in boxes – has to head into the city for an audition. On the ferry, as she scrolls through the live feed comments from her most recent encounter, she spots one less than adulatory comment asking her how she would like to be watched all the time – but hey, this is the internet. She gives it a moment’s thought, but she’s clearly quite hardened to this: to get work, she seems to mine the darkest depths of Craigslist (or a very close facsimile) and you don’t do that for too long without developing a thick skin. And anyway, business is brisk – well, at least in terms of the amount of time Jess spends interacting with her phone; sadly, it’s not as lucrative as it is time-consuming.

It gets worse when she realises that, on a new upload, the filter which is meant to obscure faces has failed, revealing the guy she was with. Clearly, she has been using these filters in lieu of actually asking these guys if she can use her footage, or indeed if she can film at all. Jess ponders whether take the video down, or keep accruing clicks, comments and revenue. The video is doing great. She needs the money. Not only is she a professional disappointment to her father, but she might be on the verge of losing her place to live. And besides, she has another job to go to, and of course to livestream.

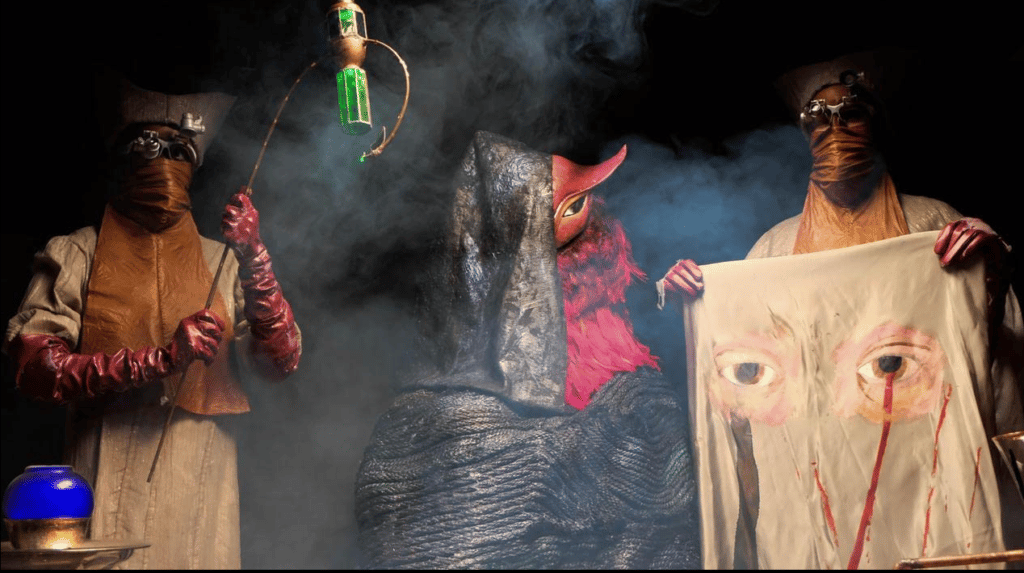

This job sounds a little different, even though Jess assumes that, once it comes down to brass tacks, it’s likely to be another unsavoury set-up masquerading as something else. But, at least ostensibly, the job is a request to work on a screenplay: a Hitchcock-aspiring writer needs the expertise of a beautiful woman (don’t they all?) to help him write a specific character, thus enabling him to complete the project. Jess agrees to meet the writer, Tom, in a rural upstate area and all’s well, at first – they even seem to be hitting it off – until she reads the script, and begins to suspect that there is more to this project than meets the eye. A kind of cat and mouse ensues – one augmented by Tom and Jess each trying to surveil one another as much as they try to outwit one another – and as this unfolds, the narrative broadens into a far bigger exploration of a certain modern, hectic, high-risk way of living. Tom begins to openly question this manner of existence, as embodied by Jess; we the audience are also invited to see the issues with this, because, even if the film begins to make use of more established horror tropes, it all feels like a very timely examination of the pitfalls of a life refracted through the internet. Jess is no mere victim in this though, and never acts like one: fighting over self-determination is not unknown to her, and she uses it.

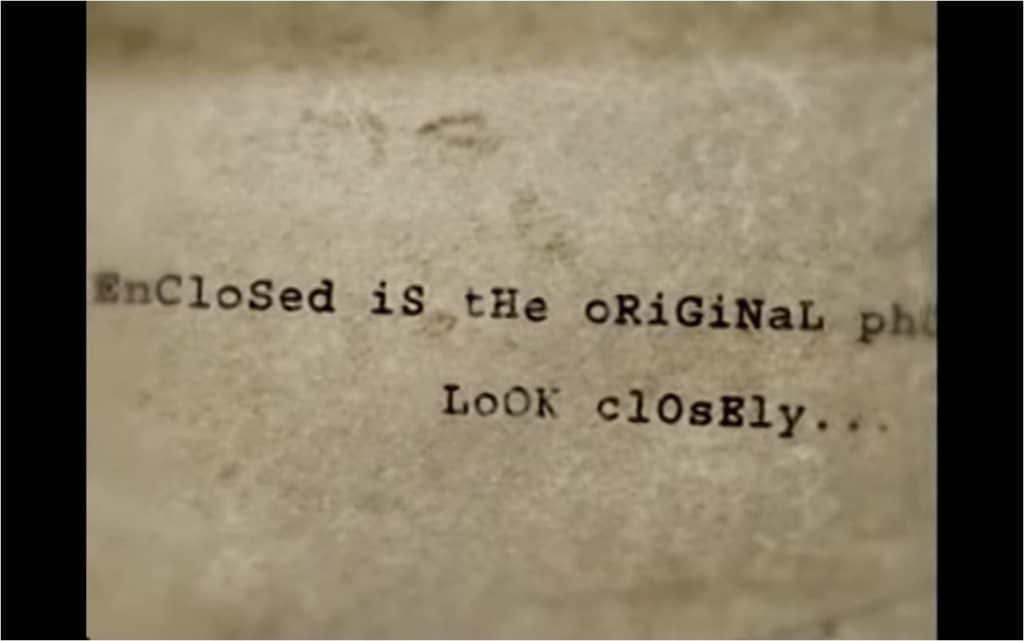

Improvisation and its nature becomes an important plot point, and the dialogue throughout seems at least in part to be improvised too, which provides the film with one of its examples of circularity: added to that, the rapport between Jess and Tom is very plausible, with plenty of self-deprecation and charm from each. Luke Cook as Tom deserves a great deal of credit for his performance here, as he vacillates between plausible and sinister and right back again. It’s a very discomfiting, if engrossing feature of the film. But then, every element here seems to have been put together very carefully to achieve its selected effect. The shooting style is layered, switching between handheld mobile phone video, laptop and more traditional camerawork; however, because the film takes the trouble to make us question who is or isn’t shooting, the usual safe remove enjoyed by an audience – confident that they are very much outside a story looking in – breaks down. We can never feel confident about who is filming, where or why. It’s another effective feature, and it works.

There have been other films which morph into ruminations on filmmaking itself, but never quite as acerbically as Follow Her: it offers a very measured insight into its subject matter, one which works well alongside the pace and energy it sustains throughout. I wondered if some of the on-screen text needed a proofread or whether that was done to deliberately emulate online grammar horror shows (surely it’s ‘mindless drivel’, not ‘dribble’?) but hey, it could be either: follower counts win these days, right? This is a sharp, savvy film and a timely one, too. There’s a lot to like here.

Follow Her (2022) screened as part of Frightfest 2022. For more information on the festival, please click here.