A confession: I am not familiar with the work of director Gaspar Noé, despite his presence as a notorious, divisive figure in the cult cinema scene. The verdict on 2002’s Irreversible was so split amongst people whose opinions I trust that I’ve still never sought the film out, and as such I’ve never caught up with anything else of his, either. All of that has changed with Climax (2018), which I am led to believe is a fairly accessible film compared to Noé’s other work, and I’d agree that there’s nothing absolutely insurmountable here for a rookie, in terms of its style and content. However, having seen Climax, I think I do now understand what all the fuss is about. It showcases a sizeable talent, with a vivid and daring array of shooting styles, overlaid with music and a building atmosphere until the film’s intended nightmarish aspects are palpable. Clearly, from the very first moments, Noé is both aware of his own skills, and keen for his film to be a disruptive experience. This he certainly achieves.

The film begins – after a sequence of what would usually be end credits, something I understand that Noé usually does – with a series of audition tapes showing a number of hopeful twenty-somethings hoping to join a modern dance group. Here’s the first way in which the film disrupts; we are clearly led to believe, via the VCR used to play the audition tapes and the big box VHS cult and horror films framing the TV screen, that this film takes place somewhere in the mid-nineties. However, in other respects, our film feels bang up to date, even without the ubiquitous presence of smartphones. Everything else – clothes, hair, style – feels like it could have been captured just yesterday. Alongside the almost expected presence of on-screen chapter titles, the tendency to blot out too many obvious markers of modernity seems to be a contemporary obsession; perhaps this, in itself, marks a film out as brand new. Anyway, these bright young things who love to dance have evidently got the job, and they head to an isolated location to practice, where they spend three days.

Things seem to have gone well and the group has seemingly bonded very well, so that after a full run-through of their act (which even if you regard most dancing as a kind of well-pruned seizure still constitutes an extraordinary long take) it’s time to unwind. They decide to have a low-key party at the rehearsal location, with a little buffet and a punch bowl of sangria, and the dancers begin to pair off, discussing everything from drugs to sex to God, with the drink still flowing. Gradually, the banter seems to be giving way to more unfriendly vibes which are billowing beneath the surface – but the real clincher is when it becomes apparent to everyone that the sangria has been spiked with a hallucinogenic. Now fearful and rapidly becoming paranoid on their way to a complete psychedelic meltdown, reproach and anger begins to ripple. The rapidity with which the party turns into a nightmare is quite something, and – in a series of sequences which are quite unrehearsed and unscripted – people demonstrate just how nuts and irrational things can get, and the film strides quite boldly from naturalistic to histrionic. It really is a force of nature, incredibly immersive and well-crafted.

Noé’s notoriety stems in large part from the themes he has tackled thus far, but he’s as well-known for his exploratory camera work, and although many of his shots here are quite low-key, he also varies this with a broad range of different aspects here. Undertaking such things as following different actors on a rig, then swapping to actor’s-eye-view and back again, all contributes hugely to the overall atmosphere and showcases a meticulous eye for detail. Then, the camera may perform a switch from ground level to ceiling, shooting the host of (amateur actors and) tripping dancers from above. There doesn’t seem to be a shot or a sequence wasted; it all flows effortlessly, but nonetheless feels like something ornate is being crafted. If the film reminds me of anything else at all, it’s of some sort of unholy matrimony between Suspiria (dance as some sort of malign link and currency) and Aronofsky’s 2017 film mother! (chaos escalating from the ridiculous to the sublime, as well as threats to an innocent child). However, I’d say I enjoy Climax’s lunacy more than I did mother! – Climax has more of an enjoyable journey towards its own casually cruel, heady final fallout.

Climax is a jagged piece of filmmaking, showcasing incredibly acuity throughout its pared-down running time, including wherever this means that vagueness and confusion contribute to its overall effect. As much a feat as a feast, it concerns itself far more with impressions than linear storytelling with a neat beginning and end, although what it achieves is immersive enough to keep you gripped anyway. In essence, it’s a simple enough yarn, but made into an effective and lurid cinematic experience. Yeah, despite a few initial misgivings, I was pleasantly blown away by this film and I can see that Arrow are again the right people to showcase this release at its best. Fans of synth/dance music will adore the soundtrack, too.

Climax will be released by Arrow Films on 11th February 2019.

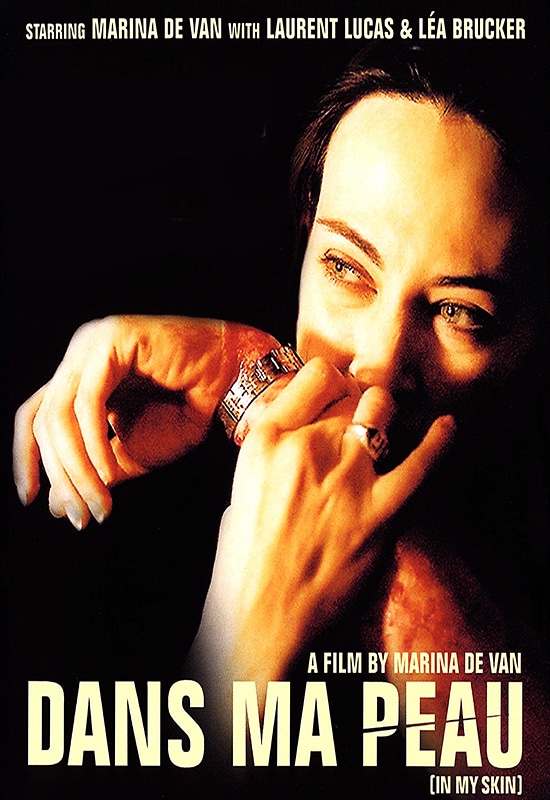

It’s been nearly fifteen years since Dans ma Peau (2004) was released, duly taking its place in the canon of New French Extremity, and garnering a great deal of justifiable praise for its transgressive nature and clarity of vision. These features alone – both the film’s age and its reputation – give us good enough reason to revisit it now. However, looking back, I wonder if its inauguration as a Noughties French horror perhaps worked against some of its strengths. For the horror crowd enamoured of the blue-hued, unflinching gore of the decade, it perhaps seemed not quite a horror film; for those engaged by its domestic and personal themes, perhaps it was too much of a horror film. But these genre-straddling films are often the most rewarding, even if difficult to categorise. Dans ma Peau is absolutely a film which has stayed in my mind – one of those rare birds where I’ve never found my recollection of the film reduced down to a gist memory. it is in so many respects a radical film, and now perhaps more than on my initial viewing, de Van’s tale bloody portrayal of mental breakdown feels like a story for our times.

It’s been nearly fifteen years since Dans ma Peau (2004) was released, duly taking its place in the canon of New French Extremity, and garnering a great deal of justifiable praise for its transgressive nature and clarity of vision. These features alone – both the film’s age and its reputation – give us good enough reason to revisit it now. However, looking back, I wonder if its inauguration as a Noughties French horror perhaps worked against some of its strengths. For the horror crowd enamoured of the blue-hued, unflinching gore of the decade, it perhaps seemed not quite a horror film; for those engaged by its domestic and personal themes, perhaps it was too much of a horror film. But these genre-straddling films are often the most rewarding, even if difficult to categorise. Dans ma Peau is absolutely a film which has stayed in my mind – one of those rare birds where I’ve never found my recollection of the film reduced down to a gist memory. it is in so many respects a radical film, and now perhaps more than on my initial viewing, de Van’s tale bloody portrayal of mental breakdown feels like a story for our times. The France of the film is a fast-paced, rather fraught world that we could all probably recognise. Everyone seems stressed by their work, everyone wants more ‘recognition’ and everyone seems to be struggling to conceal their feelings of anxiety and professional ennui. When the ‘real’ is exposed – such as when Esther’s injury bleeds through a pair of expensive (borrowed) trousers during the poolside scene – misery and vulnerability ensue. People do not like being exposed as different, but they want recognition for being different. It’s the tightrope which many must walk. Outside of the office, the carefully-domineering Vincent is difficult to watch. Whatever germ of genuine concern he might have for Esther, it quickly translates into a need to police her body. The only way a miserable woman can be stopped from self-harm is, evidently, to physically prevent her doing so. His logic is, almost inevitably, part of the problem here. Esther, faced with these escalating situations, feels the need to shut down further. When she cuts herself, she performs the film’s only tender, loving scenes. The camera lingers on these; it’s macabre, but it’s a kind of affection which is absent elsewhere, and the contrast is clear. It’s also heartbreaking that so many of the avenues which seem to be open to Esther either seem lost to her, or self-sabotaged. The hallucinatory sequence at the restaurant, for instance, is a particularly dismal distillation of that feeling, “I don’t belong here”. Hence, you end up making sure that you don’t belong. This all takes place, ironically, as the white-collar dinner table conversation extols the supreme virtues of Paris over other European cities; sadly, Esther’s Paris has few virtues for her.

The France of the film is a fast-paced, rather fraught world that we could all probably recognise. Everyone seems stressed by their work, everyone wants more ‘recognition’ and everyone seems to be struggling to conceal their feelings of anxiety and professional ennui. When the ‘real’ is exposed – such as when Esther’s injury bleeds through a pair of expensive (borrowed) trousers during the poolside scene – misery and vulnerability ensue. People do not like being exposed as different, but they want recognition for being different. It’s the tightrope which many must walk. Outside of the office, the carefully-domineering Vincent is difficult to watch. Whatever germ of genuine concern he might have for Esther, it quickly translates into a need to police her body. The only way a miserable woman can be stopped from self-harm is, evidently, to physically prevent her doing so. His logic is, almost inevitably, part of the problem here. Esther, faced with these escalating situations, feels the need to shut down further. When she cuts herself, she performs the film’s only tender, loving scenes. The camera lingers on these; it’s macabre, but it’s a kind of affection which is absent elsewhere, and the contrast is clear. It’s also heartbreaking that so many of the avenues which seem to be open to Esther either seem lost to her, or self-sabotaged. The hallucinatory sequence at the restaurant, for instance, is a particularly dismal distillation of that feeling, “I don’t belong here”. Hence, you end up making sure that you don’t belong. This all takes place, ironically, as the white-collar dinner table conversation extols the supreme virtues of Paris over other European cities; sadly, Esther’s Paris has few virtues for her. The thing is though, as far as Esther is concerned, once you can live one lie, you can live more than one. Not effectively, but you can. Esther is willing to perform great feats of concealment to excuse her physical condition; later, de Van’s series of split screens encapsulates Esther’s great divide between real self and unreal self. Only later do they conjoin and show us what Esther’s doing – a kind of performance art of mutilation, done on the quiet in a sequence of ever grubbier, anonymous hotel rooms. It’s in one of these rooms that we finally leave her, having thought at first that, even given her final physical condition (with large cuts and abrasions on her face, and at least one severed piece of skin which she wants to preserve) she is about to attempt to return to her job.

The thing is though, as far as Esther is concerned, once you can live one lie, you can live more than one. Not effectively, but you can. Esther is willing to perform great feats of concealment to excuse her physical condition; later, de Van’s series of split screens encapsulates Esther’s great divide between real self and unreal self. Only later do they conjoin and show us what Esther’s doing – a kind of performance art of mutilation, done on the quiet in a sequence of ever grubbier, anonymous hotel rooms. It’s in one of these rooms that we finally leave her, having thought at first that, even given her final physical condition (with large cuts and abrasions on her face, and at least one severed piece of skin which she wants to preserve) she is about to attempt to return to her job. The first clue that all is not well with friends (and fast food connoisseurs) Tan and Javid is that, as they leave a Berlin kebab restaurant which has apparently not passed muster, they have to step over a lot of dead bodies as they go. In a neat move, then, Snowflake establishes key elements in its modus operandi: naturalistic dialogue, strong links with the criminal underworld and a little dash of absurdity which works broadly well with all of the rest. But there’s more. Snowflake is, as a voiceover tells us briefly, a ‘true story’ – well, sort of a true story. It’s coming to us from a point in the near future, actually, and a Berlin where law and order has entirely broken down, so much so that people are left desperately trying to go about their day-to-day business as lunatics and hitmen run the streets. Tan and Javid belong to that world.

The first clue that all is not well with friends (and fast food connoisseurs) Tan and Javid is that, as they leave a Berlin kebab restaurant which has apparently not passed muster, they have to step over a lot of dead bodies as they go. In a neat move, then, Snowflake establishes key elements in its modus operandi: naturalistic dialogue, strong links with the criminal underworld and a little dash of absurdity which works broadly well with all of the rest. But there’s more. Snowflake is, as a voiceover tells us briefly, a ‘true story’ – well, sort of a true story. It’s coming to us from a point in the near future, actually, and a Berlin where law and order has entirely broken down, so much so that people are left desperately trying to go about their day-to-day business as lunatics and hitmen run the streets. Tan and Javid belong to that world. It’s always a risky business, making these kinds of films which have been described as ‘meta’: not for nothing did ‘meta’ become an insult fairly soon after it was first used to describe films which for instance step outside the universe of the narrative, suggesting other things at play and, to a certain extent at least, manipulating audience expectations. This approach can lead to great films, but it’s a divisive strategy which can backfire (and lob in some mumblecore elements, as here, to really take a gamble). Happily, Snowflake feels less like it’s aching to show off how self-aware it is and far more interested in telling a weird, unusual story, which helps it to make a success of this approach. There are many things to recommend it. To start with, this is a well-shot and aesthetically-pleasing film, but beyond its good looks it handles its many at first disparate elements with a wry, often subtle humour which works well, never seeming arrogant or smug. Snowflake is organically very funny, and there’s a sense of confident handling, of close control over where the film is going and how the audience might respond. Added in to that mix is some erudite commentary on the creative process – writer’s block, finding an ending, making the story work. Or, is it all about fate?

It’s always a risky business, making these kinds of films which have been described as ‘meta’: not for nothing did ‘meta’ become an insult fairly soon after it was first used to describe films which for instance step outside the universe of the narrative, suggesting other things at play and, to a certain extent at least, manipulating audience expectations. This approach can lead to great films, but it’s a divisive strategy which can backfire (and lob in some mumblecore elements, as here, to really take a gamble). Happily, Snowflake feels less like it’s aching to show off how self-aware it is and far more interested in telling a weird, unusual story, which helps it to make a success of this approach. There are many things to recommend it. To start with, this is a well-shot and aesthetically-pleasing film, but beyond its good looks it handles its many at first disparate elements with a wry, often subtle humour which works well, never seeming arrogant or smug. Snowflake is organically very funny, and there’s a sense of confident handling, of close control over where the film is going and how the audience might respond. Added in to that mix is some erudite commentary on the creative process – writer’s block, finding an ending, making the story work. Or, is it all about fate? Mike Flanagan gets it. He gets the power of horror, and he doesn’t seek to delegitimise that power by needlessly talking it up or talking it down; with his work adapting Stephen King, his films such as Oculus and (the rarely-mentioned, but superb) Absentia and now, his work directing and co-writing an innovative rendition of Shirley Jackson’s novel, The Haunting of Hill House, he’s successfully established himself as one of the most ambitious and sensitive directors currently working out there. Already, there is some discussion of a second season of The Haunting of Hill House, this year’s big TV horror hit and the subject of this feature. It’s difficult to envisage quite where this could go, or from what point, or indeed how, or if the ill-fated Crain family could be a part of this second season, but we know enough by now to know that whatever Mr Flanagan might turn his hand to would be worthwhile. Mike Flanagan gets it.

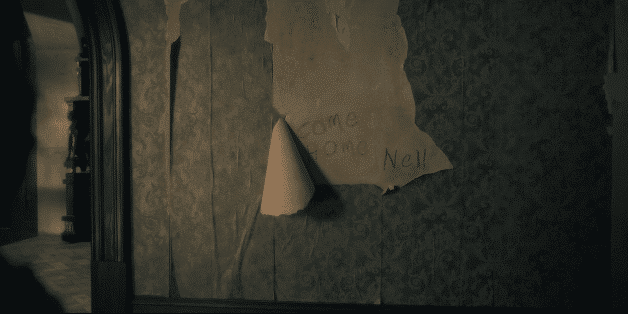

Mike Flanagan gets it. He gets the power of horror, and he doesn’t seek to delegitimise that power by needlessly talking it up or talking it down; with his work adapting Stephen King, his films such as Oculus and (the rarely-mentioned, but superb) Absentia and now, his work directing and co-writing an innovative rendition of Shirley Jackson’s novel, The Haunting of Hill House, he’s successfully established himself as one of the most ambitious and sensitive directors currently working out there. Already, there is some discussion of a second season of The Haunting of Hill House, this year’s big TV horror hit and the subject of this feature. It’s difficult to envisage quite where this could go, or from what point, or indeed how, or if the ill-fated Crain family could be a part of this second season, but we know enough by now to know that whatever Mr Flanagan might turn his hand to would be worthwhile. Mike Flanagan gets it. The Haunting of Hill House does so much so well, it’s difficult to know where to start, but certainly its handling of characterisation is a high point. Things are gradual. You soon identify that many of the adults in the story are also the children in the story: running these time periods parallel both makes perfect sense, and adds to the slightly disorientating feelings encouraged by the narrative at every turn. It also begs many questions, and only slowly allows us to understand the justifications for the things these children go on to do with their lives – the childhood traumas that lead them to push against death, or psychic ability, or life in general.

The Haunting of Hill House does so much so well, it’s difficult to know where to start, but certainly its handling of characterisation is a high point. Things are gradual. You soon identify that many of the adults in the story are also the children in the story: running these time periods parallel both makes perfect sense, and adds to the slightly disorientating feelings encouraged by the narrative at every turn. It also begs many questions, and only slowly allows us to understand the justifications for the things these children go on to do with their lives – the childhood traumas that lead them to push against death, or psychic ability, or life in general. This comes to the fore with maximum effect in Episode 5, ‘The Bent Neck Lady’. Since childhood, Nell has been afflicted with a malevolent visitation at night – a woman, face obscured, with her neck fixed at an unnatural angle. With a child’s literalness, the so-named ‘bent-neck lady’ seems to appear only to Nell, terrifying the child and driving her out of her bedroom, only to follow her downstairs to appear to her again. We follow Nell into adulthood and the events which subsume her, her short-lived happiness dissolving as her old roommate begins appearing again. This episode neatly encapsulates many of The Haunting of Hill House’s strongest features: it links ideas about time being not linear, but episodic, fate being inescapable, and the house getting its way. Poor Nell only truly understands all of this in the last frames, with that horrific ‘clunk’ as one scene rolls back in time, then back again. It truly is a staggering piece of television. Episode 8: ‘Witness Marks’ is another stand-out component of the overall series for me, with its invitation to think again about what has been seen, and is therefore ‘real’. There’s a sense of things and people unravelling here, which for me generates the strongest feeling of inescapability and a sense that the house will get everything it wants. Many of the ghosts (again, are they indeed ghosts?) are fully lit, fleshly bodies in this episode; we are encouraged to doubt them, and to think back across things we may have accepted throughout the series, before doubting everything. In less subtle terms, this episode also contains a jump scare like no other: whilst I’m not ordinarily a fan of these, it disrupts brilliantly here. I don’t think I’ve ever screamed out loud like that at anything I’ve seen on a screen, but my god, it’s a powerful shock.

This comes to the fore with maximum effect in Episode 5, ‘The Bent Neck Lady’. Since childhood, Nell has been afflicted with a malevolent visitation at night – a woman, face obscured, with her neck fixed at an unnatural angle. With a child’s literalness, the so-named ‘bent-neck lady’ seems to appear only to Nell, terrifying the child and driving her out of her bedroom, only to follow her downstairs to appear to her again. We follow Nell into adulthood and the events which subsume her, her short-lived happiness dissolving as her old roommate begins appearing again. This episode neatly encapsulates many of The Haunting of Hill House’s strongest features: it links ideas about time being not linear, but episodic, fate being inescapable, and the house getting its way. Poor Nell only truly understands all of this in the last frames, with that horrific ‘clunk’ as one scene rolls back in time, then back again. It truly is a staggering piece of television. Episode 8: ‘Witness Marks’ is another stand-out component of the overall series for me, with its invitation to think again about what has been seen, and is therefore ‘real’. There’s a sense of things and people unravelling here, which for me generates the strongest feeling of inescapability and a sense that the house will get everything it wants. Many of the ghosts (again, are they indeed ghosts?) are fully lit, fleshly bodies in this episode; we are encouraged to doubt them, and to think back across things we may have accepted throughout the series, before doubting everything. In less subtle terms, this episode also contains a jump scare like no other: whilst I’m not ordinarily a fan of these, it disrupts brilliantly here. I don’t think I’ve ever screamed out loud like that at anything I’ve seen on a screen, but my god, it’s a powerful shock. Nell is not about to sleep in her bedroom, after being woken by the ghost of a lady who seems to be fixated on her. But as she sleeps on the couch downstairs, something alerts her. As she looks up, there’s the ‘bent neck lady’ again, floating parallel above her – as we realise as the camera pans around. She’s feebly trying to speak to Nell; what she says makes horrible sense later.

Nell is not about to sleep in her bedroom, after being woken by the ghost of a lady who seems to be fixated on her. But as she sleeps on the couch downstairs, something alerts her. As she looks up, there’s the ‘bent neck lady’ again, floating parallel above her – as we realise as the camera pans around. She’s feebly trying to speak to Nell; what she says makes horrible sense later. Oh, Luke. Your subsequent drug use makes perfect sense, given some of the things which happened to you as a kid. This time, the twins are playing with the dumb waiter in the kitchen, which is electronically-operated (oh-oh). Luke, who wants to ride in the dumb waiter, finds himself in an unlit, cluttered cellar room that the family never knew existed. Something, disturbed at last, crawls eagerly towards him…

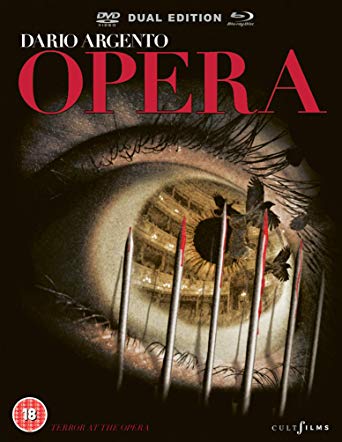

Oh, Luke. Your subsequent drug use makes perfect sense, given some of the things which happened to you as a kid. This time, the twins are playing with the dumb waiter in the kitchen, which is electronically-operated (oh-oh). Luke, who wants to ride in the dumb waiter, finds himself in an unlit, cluttered cellar room that the family never knew existed. Something, disturbed at last, crawls eagerly towards him… I start this review with something of a confession: it has only dawned on me in the past few years, really, that my liking for Dario Argento’s work is based on a very small number of his films. And it’s awful – as well as terribly unpopular these days, given the vicissitudes of the likes of ‘film Twitter’ and so on – to have to start a piece of writing on a negative note, but I still can’t help but wonder whether a lot of Argento’s cult following stems from blind luck and happy accidents, rather than a cogent approach and intention on his part from the beginning of his career. Yes, he has a strong aesthetic style, often distilled into a number of notorious key scenes per film, but given time and money, he has never really scaled to the heights of Suspiria (1977) in his subsequent work. This brings me, then, to Opera (1987), made a full decade after Suspiria, and a film that, whilst showcasing some of that Argento magic, flounders in a number of ways which ultimately break the spell.

I start this review with something of a confession: it has only dawned on me in the past few years, really, that my liking for Dario Argento’s work is based on a very small number of his films. And it’s awful – as well as terribly unpopular these days, given the vicissitudes of the likes of ‘film Twitter’ and so on – to have to start a piece of writing on a negative note, but I still can’t help but wonder whether a lot of Argento’s cult following stems from blind luck and happy accidents, rather than a cogent approach and intention on his part from the beginning of his career. Yes, he has a strong aesthetic style, often distilled into a number of notorious key scenes per film, but given time and money, he has never really scaled to the heights of Suspiria (1977) in his subsequent work. This brings me, then, to Opera (1987), made a full decade after Suspiria, and a film that, whilst showcasing some of that Argento magic, flounders in a number of ways which ultimately break the spell. There were a few of these ‘performances of performances’ horror films during this era; everything from Waxwork to Demons could qualify. However, Opera’s closest comparison piece is almost certainly StageFright, directed by Argento’s associate and countryman Michele Soavi and released earlier the same year. The links are clear: Stagefright also boasts a mysterious killer stalking around an arts venue, seemingly fascinated by elements of the performance itself whilst picking off the performers and crew in a series of ways which happened to give good set pieces. Opera broadens its remit rather more widely than StageFright in the end, moving the action beyond the opera house and following Betty wherever she goes (which turns out to be quite a long way indeed) but I have to say that I think StageFright has the edge on Argento’s offering. For me, it’s more tightly plotted and coherent, lacking some of the frankly oddball decisions which are perhaps intended to lighten the mood in Opera, but dilute the appeal instead. For instance, why the former leading lady Mara appears in the film as nothing more than a shrill voice and a pair of legs is beyond me; it put me in mind of the ‘mammy’ character from Tom and Jerry, which isn’t a comparison I expected to make here. Then, even given my usual delight in viewing an 80s (or indeed any era) time capsule, the costumes are distractingly weird, the script is wincingly stilted and there are even some weak, clownish moments, which rest uncomfortably with the eventual grisly content. Opera simply underlines for me that Argento depends on atmosphere, with a good eye for key shots which underpin this atmosphere: plot/dialogue so often falls flat.

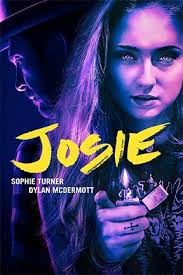

There were a few of these ‘performances of performances’ horror films during this era; everything from Waxwork to Demons could qualify. However, Opera’s closest comparison piece is almost certainly StageFright, directed by Argento’s associate and countryman Michele Soavi and released earlier the same year. The links are clear: Stagefright also boasts a mysterious killer stalking around an arts venue, seemingly fascinated by elements of the performance itself whilst picking off the performers and crew in a series of ways which happened to give good set pieces. Opera broadens its remit rather more widely than StageFright in the end, moving the action beyond the opera house and following Betty wherever she goes (which turns out to be quite a long way indeed) but I have to say that I think StageFright has the edge on Argento’s offering. For me, it’s more tightly plotted and coherent, lacking some of the frankly oddball decisions which are perhaps intended to lighten the mood in Opera, but dilute the appeal instead. For instance, why the former leading lady Mara appears in the film as nothing more than a shrill voice and a pair of legs is beyond me; it put me in mind of the ‘mammy’ character from Tom and Jerry, which isn’t a comparison I expected to make here. Then, even given my usual delight in viewing an 80s (or indeed any era) time capsule, the costumes are distractingly weird, the script is wincingly stilted and there are even some weak, clownish moments, which rest uncomfortably with the eventual grisly content. Opera simply underlines for me that Argento depends on atmosphere, with a good eye for key shots which underpin this atmosphere: plot/dialogue so often falls flat. It must be incredibly hard to carve a new niche for yourself as an actor when you’re largely known for one role, but – as Game of Thrones is about to enter its final ever season – this is something the cast are going to have to negotiate; that is, unless they’re doing it already. Josie, starring Sophie ‘Sansa Stark’ Turner, is at least a fair attempt by this actress to do something rather different, and – on paper at least – it’s an interesting premise, promising ‘rural noir’ and dangerous obsessions spilling over into action. We know that bad things are definitely going to happen, as the opening scenes show us police kicking their way into a room; the only question, then, is how we get to this point. Unfortunately, the journey which takes us there isn’t able to sustain the initial promise.

It must be incredibly hard to carve a new niche for yourself as an actor when you’re largely known for one role, but – as Game of Thrones is about to enter its final ever season – this is something the cast are going to have to negotiate; that is, unless they’re doing it already. Josie, starring Sophie ‘Sansa Stark’ Turner, is at least a fair attempt by this actress to do something rather different, and – on paper at least – it’s an interesting premise, promising ‘rural noir’ and dangerous obsessions spilling over into action. We know that bad things are definitely going to happen, as the opening scenes show us police kicking their way into a room; the only question, then, is how we get to this point. Unfortunately, the journey which takes us there isn’t able to sustain the initial promise. As for Sophie Turner, she does a reasonable job with the script and the direction she’s given, but she doesn’t quite cut it as a Lolita character which, frequently, the film seems to be implying she is – but any sexuality is shied away from, or takes place off-screen, leaving the allure which is integral to her motivations and her interactions with the men in her life a little lacklustre. The film waves through her rather unconvincing Southern accent by having her say she’s lived all over the country, but this is another factor which holds the audience at bay; she just isn’t quite in the role, to me, and I really don’t think that this is the role to silence Sansa for good.

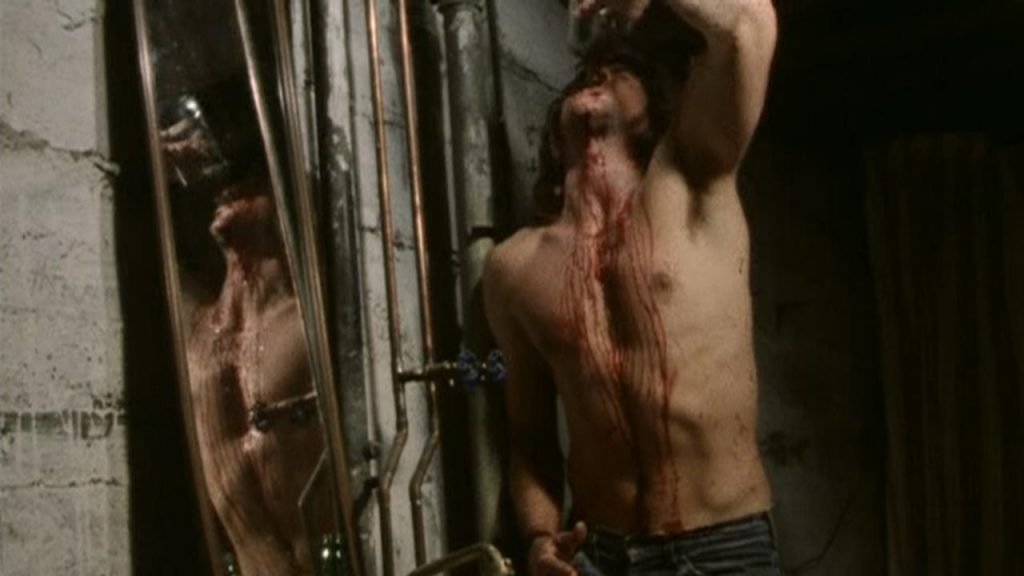

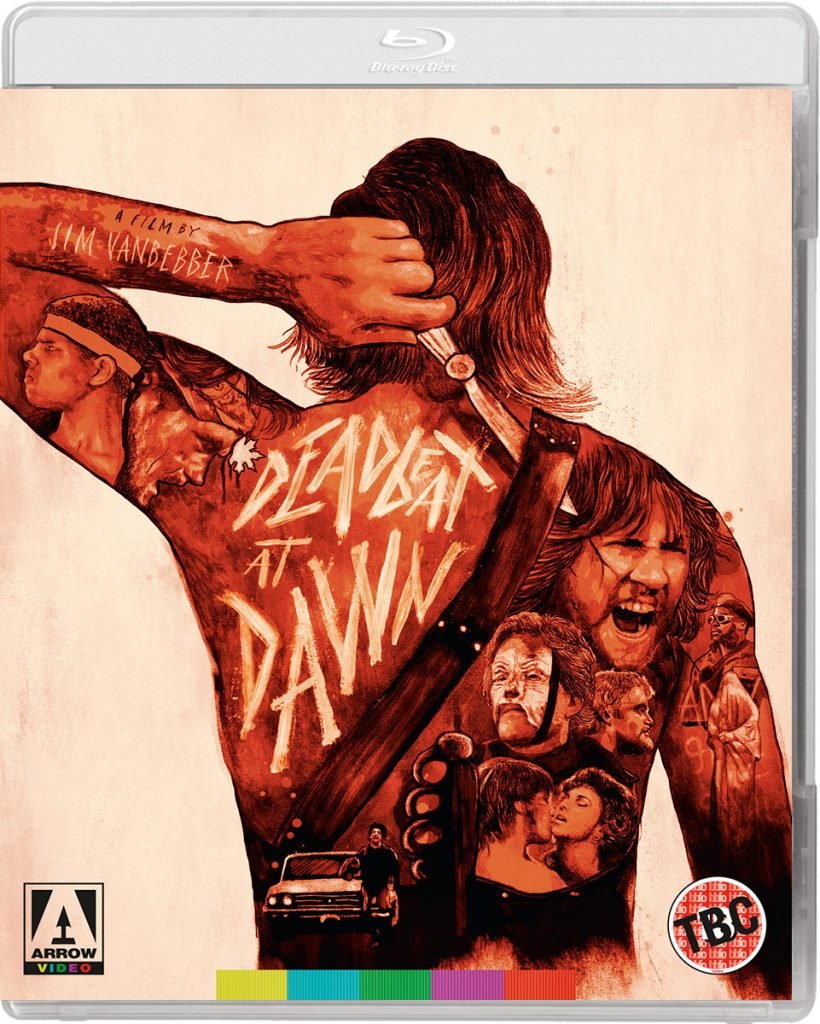

As for Sophie Turner, she does a reasonable job with the script and the direction she’s given, but she doesn’t quite cut it as a Lolita character which, frequently, the film seems to be implying she is – but any sexuality is shied away from, or takes place off-screen, leaving the allure which is integral to her motivations and her interactions with the men in her life a little lacklustre. The film waves through her rather unconvincing Southern accent by having her say she’s lived all over the country, but this is another factor which holds the audience at bay; she just isn’t quite in the role, to me, and I really don’t think that this is the role to silence Sansa for good. I’ve really only encountered director Jim Van Bebber thus far through his art-house spin on The Manson Family (1997), a film which I confess didn’t quite gel with me – but I’ve never, until now, seen his first feature Deadbeat at Dawn, made around a decade earlier but filmed over four years altogether. Deadbeat at Dawn is certainly more linear than The Manson Family, but it’s still a surprisingly multi-layered spin on your standard gang movie, with some hints of the art-house approach yet to come. All in all, it makes for a gritty but expansive experience, something quite unlike any of the other 80s gang movies made during the decade, whilst still recognisably part of that sub-genre.

I’ve really only encountered director Jim Van Bebber thus far through his art-house spin on The Manson Family (1997), a film which I confess didn’t quite gel with me – but I’ve never, until now, seen his first feature Deadbeat at Dawn, made around a decade earlier but filmed over four years altogether. Deadbeat at Dawn is certainly more linear than The Manson Family, but it’s still a surprisingly multi-layered spin on your standard gang movie, with some hints of the art-house approach yet to come. All in all, it makes for a gritty but expansive experience, something quite unlike any of the other 80s gang movies made during the decade, whilst still recognisably part of that sub-genre. But then, the film does far more than make a series of knowing nods here and there in-between the fight scenes. The gang warfare itself veers from plausible to risible in some places: Goose’s training sequences look oddly choreographed, for instance, and dialogue spoken by some of the Spiders sounds rather stagey. In effect, lots of elements of Deadbeat at Dawn play out like modern Grand Guignol: this is definitely performance, but the subject matter is ferocious and no one gets off lightly. The worst of the violence might not be on-screen in the nature of the ‘torture porn’ which followed the film around a decade or so later, but the well-timed glimpses and insinuations of the horrors inflicted upon people work just as well as the longer sequences (saved for an incredible later pay-off which very definitely shows us the works, with Van Bebber more than paying his dues by doing his own stunts during the course of the action). Yes, there are a few lulls as Goose falls back and regroups, but these add a lot to his character. In the end, you do find yourself rooting for this anti-hero, which is no small thing given his behaviour throughout the film.

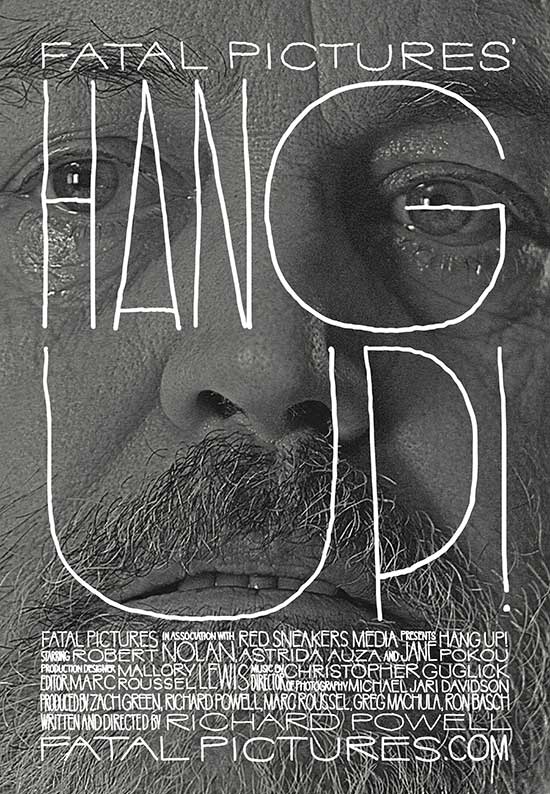

But then, the film does far more than make a series of knowing nods here and there in-between the fight scenes. The gang warfare itself veers from plausible to risible in some places: Goose’s training sequences look oddly choreographed, for instance, and dialogue spoken by some of the Spiders sounds rather stagey. In effect, lots of elements of Deadbeat at Dawn play out like modern Grand Guignol: this is definitely performance, but the subject matter is ferocious and no one gets off lightly. The worst of the violence might not be on-screen in the nature of the ‘torture porn’ which followed the film around a decade or so later, but the well-timed glimpses and insinuations of the horrors inflicted upon people work just as well as the longer sequences (saved for an incredible later pay-off which very definitely shows us the works, with Van Bebber more than paying his dues by doing his own stunts during the course of the action). Yes, there are a few lulls as Goose falls back and regroups, but these add a lot to his character. In the end, you do find yourself rooting for this anti-hero, which is no small thing given his behaviour throughout the film. Every year, if we’re lucky, we’ll encounter a short film at a festival which just blows us away. The affordances and limitations of the short movie medium provides so many opportunities for filmmakers to showcase their ideas, making them render these ideas in an economical manner, but nonetheless – if successful – weaving a story which indelibly stays with the audience. This is very much the case with a short film I encountered at this year’s Celluloid Screams Festival in Sheffield, UK. Hang Up! takes a very simple idea – that of someone making a mobile phone call by accident, just like we all have – and takes this idea forward, escalating the tension in a series of hand-over-mouth shocking ways, as husband Gary finds himself listening in on a conversation his wife, Emelia, is having about him. It turns out that his happy, stable life is anything but – and his wife doesn’t feel about him the way she has been enacting over the years. It’s a plausible, everyday set-up – and director/writer Richard Powell develops this horrid, believable framework in an engrossing manner.

Every year, if we’re lucky, we’ll encounter a short film at a festival which just blows us away. The affordances and limitations of the short movie medium provides so many opportunities for filmmakers to showcase their ideas, making them render these ideas in an economical manner, but nonetheless – if successful – weaving a story which indelibly stays with the audience. This is very much the case with a short film I encountered at this year’s Celluloid Screams Festival in Sheffield, UK. Hang Up! takes a very simple idea – that of someone making a mobile phone call by accident, just like we all have – and takes this idea forward, escalating the tension in a series of hand-over-mouth shocking ways, as husband Gary finds himself listening in on a conversation his wife, Emelia, is having about him. It turns out that his happy, stable life is anything but – and his wife doesn’t feel about him the way she has been enacting over the years. It’s a plausible, everyday set-up – and director/writer Richard Powell develops this horrid, believable framework in an engrossing manner. The response has been great! I think the film is unique, especially in today’s short film climate. I’m asking an audience to wait and listen and be patient, and that isn’t something they are used to in the short film medium. I think that alone creates a rewarding experience. I’ve watched people watching the film and it holds them, despite how static and paced it is; there’s a kind of perverse voyeurism in spying on Gary as his life falls apart while spying on his wife. You feel like you’re hearing and seeing things you shouldn’t be and there is a thrill to it all. I also think the film is darkly funny which makes it palatable considering where it ends up going. I just love that I can have a theatre full of people watch what is essentially a 14 minute monologue and be entertained and disturbed with words and acting and careful shot selection!

The response has been great! I think the film is unique, especially in today’s short film climate. I’m asking an audience to wait and listen and be patient, and that isn’t something they are used to in the short film medium. I think that alone creates a rewarding experience. I’ve watched people watching the film and it holds them, despite how static and paced it is; there’s a kind of perverse voyeurism in spying on Gary as his life falls apart while spying on his wife. You feel like you’re hearing and seeing things you shouldn’t be and there is a thrill to it all. I also think the film is darkly funny which makes it palatable considering where it ends up going. I just love that I can have a theatre full of people watch what is essentially a 14 minute monologue and be entertained and disturbed with words and acting and careful shot selection! Nicolas Cage has to be one of the most divisive actors out there, as well as one of the most hard-working; in fact, these days it’s actually pretty odd for an actor to garner the kinds of mixed feelings which he inspires, but everyone seemingly has an opinion about his extensive body of work. For me, he swings from borderline unwatchable (Vampire’s Kiss, ack) to phenomenal (Leaving Las Vegas is simply brilliant, just as an example). All I knew then, going in to see Mandy, was one thing: I knew nothing at all about the plot, but I did know that I could expect to see ‘peak Nicolas Cage’ in the film. And, oh my, this is the case. Gloriously so. Mandy also happens to be a perfect vehicle for its lead actor, and one of the best films I’ve ever seen him in. Whilst fairly plot lite, the film’s pace and ambience makes for a thrilling, engrossing viewing experience. I’d say that this could be the best film I’ve seen this year.

Nicolas Cage has to be one of the most divisive actors out there, as well as one of the most hard-working; in fact, these days it’s actually pretty odd for an actor to garner the kinds of mixed feelings which he inspires, but everyone seemingly has an opinion about his extensive body of work. For me, he swings from borderline unwatchable (Vampire’s Kiss, ack) to phenomenal (Leaving Las Vegas is simply brilliant, just as an example). All I knew then, going in to see Mandy, was one thing: I knew nothing at all about the plot, but I did know that I could expect to see ‘peak Nicolas Cage’ in the film. And, oh my, this is the case. Gloriously so. Mandy also happens to be a perfect vehicle for its lead actor, and one of the best films I’ve ever seen him in. Whilst fairly plot lite, the film’s pace and ambience makes for a thrilling, engrossing viewing experience. I’d say that this could be the best film I’ve seen this year. I told you it was plot lite and it is, but this is by no means a bad thing; Mandy is more of an aural/visual experience than it is a detailed story, and the characters’ predilection for mind-altering substances gets passed on to the audience via the film’s incredible colour palettes, detailed asides into fictional worlds, pulsing soundtrack and overall talent for hyperbole. Red glowers, grimaces and screams his way through his ordeal, turning into more of a supernatural force than a man. Likewise, the cult members are larger than life themselves, and no pushovers. The biker gang are more like cenobites than regular beings, and the overblown, quasi-religious psychobabble coming from the cultists is matched against their extraordinarily cruel behaviour – Jeremiah in particular (played with full frontal aplomb by Linus Roache) is a deeply menacing figure, very arresting on screen. It’s interesting that the film takes for its title the name of a character who isn’t actually in the film for very long: however, it feels as though Mandy (British actress Andrea Riseborough) is present throughout, even if only as the driving factor behind Red’s escalating lunacy. The film’s quick, almost frenetic pace after the initial assault, supported by varied approaches such as animated sequences and on-screen text, make the film dreamlike, like a fractured memory of something so outlandish it could hardly be believed.

I told you it was plot lite and it is, but this is by no means a bad thing; Mandy is more of an aural/visual experience than it is a detailed story, and the characters’ predilection for mind-altering substances gets passed on to the audience via the film’s incredible colour palettes, detailed asides into fictional worlds, pulsing soundtrack and overall talent for hyperbole. Red glowers, grimaces and screams his way through his ordeal, turning into more of a supernatural force than a man. Likewise, the cult members are larger than life themselves, and no pushovers. The biker gang are more like cenobites than regular beings, and the overblown, quasi-religious psychobabble coming from the cultists is matched against their extraordinarily cruel behaviour – Jeremiah in particular (played with full frontal aplomb by Linus Roache) is a deeply menacing figure, very arresting on screen. It’s interesting that the film takes for its title the name of a character who isn’t actually in the film for very long: however, it feels as though Mandy (British actress Andrea Riseborough) is present throughout, even if only as the driving factor behind Red’s escalating lunacy. The film’s quick, almost frenetic pace after the initial assault, supported by varied approaches such as animated sequences and on-screen text, make the film dreamlike, like a fractured memory of something so outlandish it could hardly be believed. The opening scenes of Knife + Heart feel achingly familiar: how many films start with a woman in peril, running alone through the dark? Well, this is a film which doesn’t mind turning things on their head, even if the surprises are momentary. Anne (Vanessa Paradis) isn’t running from an assailant; she’s having a minor breakdown instead, and when she phones her girlfriend Lois for moral support in the early hours, it proves to be the final straw for her partner of ten years, who breaks off their relationship. It seems as though these drink-fuelled meltdowns are not so unusual. Anne is devastated, but we don’t see her showing weakness to this extent again. She simply gets back to work as a gay porn director, always looking for novel ideas and approaches to use in her films. She regularly sees Lois, who is also her film editor, but she’s trying to get on with her life whilst respecting Lois’s wishes, so they keep a discreet distance.

The opening scenes of Knife + Heart feel achingly familiar: how many films start with a woman in peril, running alone through the dark? Well, this is a film which doesn’t mind turning things on their head, even if the surprises are momentary. Anne (Vanessa Paradis) isn’t running from an assailant; she’s having a minor breakdown instead, and when she phones her girlfriend Lois for moral support in the early hours, it proves to be the final straw for her partner of ten years, who breaks off their relationship. It seems as though these drink-fuelled meltdowns are not so unusual. Anne is devastated, but we don’t see her showing weakness to this extent again. She simply gets back to work as a gay porn director, always looking for novel ideas and approaches to use in her films. She regularly sees Lois, who is also her film editor, but she’s trying to get on with her life whilst respecting Lois’s wishes, so they keep a discreet distance. Along the way, the film also plays with ideas of whether art imitates life, life imitates art, or whether the whole process is somehow cyclical. Anne, always the experimenter when it comes to her work, begins to use the unfolding case as a the inspiration for a very unusual kind of film, writing the real life goings-on into a script and filming a weird new hybrid of erotica and horror. It also transpires that the rest of her filmography plays a key role in the plot, too. All of this – bearing in mind that Knife + Heart is set in 1979 – allows for some glorious visuals. Sequences from Anne’s films are all refracted through plausibly vintage camera and celluloid, though the film itself is just as carefully framed and styled, with rich use of colour and a careful eye for stylistics. The M83 soundtrack is great, too, and fits really well. Paradis, a veteran actress albeit primarily in Francophone cinema, fits the bill perfectly here: whilst you don’t get particularly close to her character, I think that works given the context of the plot, and she looks great, with (and pardon me this observation) a fantastic aesthetic and wardrobe. In fact, it’s nice to see that the two lead female actresses are somewhat older, whilst it’s the guys that are far younger; it’s not an inversion which will change your life, granted, but it’s somewhat refreshing nonetheless, and I didn’t feel that this was simply driven by our current predilection for ‘subverting expectations’ by dithering with gender roles. It just works nicely. There are some very angry user reviews on IMDb complaining about the gay content, though I have to say that after the initial mild surprise of it being men not women getting it on FOR A CHANGE, it too simply settles down as a plot device, a reasonable framework for the rest of the film which allows interesting exploration of its themes.

Along the way, the film also plays with ideas of whether art imitates life, life imitates art, or whether the whole process is somehow cyclical. Anne, always the experimenter when it comes to her work, begins to use the unfolding case as a the inspiration for a very unusual kind of film, writing the real life goings-on into a script and filming a weird new hybrid of erotica and horror. It also transpires that the rest of her filmography plays a key role in the plot, too. All of this – bearing in mind that Knife + Heart is set in 1979 – allows for some glorious visuals. Sequences from Anne’s films are all refracted through plausibly vintage camera and celluloid, though the film itself is just as carefully framed and styled, with rich use of colour and a careful eye for stylistics. The M83 soundtrack is great, too, and fits really well. Paradis, a veteran actress albeit primarily in Francophone cinema, fits the bill perfectly here: whilst you don’t get particularly close to her character, I think that works given the context of the plot, and she looks great, with (and pardon me this observation) a fantastic aesthetic and wardrobe. In fact, it’s nice to see that the two lead female actresses are somewhat older, whilst it’s the guys that are far younger; it’s not an inversion which will change your life, granted, but it’s somewhat refreshing nonetheless, and I didn’t feel that this was simply driven by our current predilection for ‘subverting expectations’ by dithering with gender roles. It just works nicely. There are some very angry user reviews on IMDb complaining about the gay content, though I have to say that after the initial mild surprise of it being men not women getting it on FOR A CHANGE, it too simply settles down as a plot device, a reasonable framework for the rest of the film which allows interesting exploration of its themes. Tigers Are Not Afraid spins some uncomfortable truths about life in Mexican border towns into a fantastical yarn. In so doing, it embeds its characters in a fairy tale, inviting the audience to see the tale through to the end, and to look for tropes we all recognise. The besieged princess, the ogre, the magical creatures, the three wishes…all present, but all interlaced with realistic horrors. It’s an interesting film which accomplishes a great deal.

Tigers Are Not Afraid spins some uncomfortable truths about life in Mexican border towns into a fantastical yarn. In so doing, it embeds its characters in a fairy tale, inviting the audience to see the tale through to the end, and to look for tropes we all recognise. The besieged princess, the ogre, the magical creatures, the three wishes…all present, but all interlaced with realistic horrors. It’s an interesting film which accomplishes a great deal. All the while, more and more supernatural phenomena are plaguing Estrella. The ghosts of the Huascas’ victims are following her, terrifying her as they implore her to bring them the gang that murdered them. Blood literally and metaphorically begins to course through the children’s lives; dragons and tigers leap from walls and objects; the dead return and speak. Eventually fantasy and reality overlap, stories come to life, but at great cost to people who have already lost a great deal.

All the while, more and more supernatural phenomena are plaguing Estrella. The ghosts of the Huascas’ victims are following her, terrifying her as they implore her to bring them the gang that murdered them. Blood literally and metaphorically begins to course through the children’s lives; dragons and tigers leap from walls and objects; the dead return and speak. Eventually fantasy and reality overlap, stories come to life, but at great cost to people who have already lost a great deal.