In recent years, no doubt as a result of changing social attitudes and debates, there’s been a steadily-increasing number of films which – subtly or less subtly – interrogate the relationships between men and women. This is their specific modus operandi, rather than incidental to the story. Men (2022) makes no secret of its modus operandi; it’s overt from the opening scenes. It also opts very much for a horror lens, distorting and refracting its key ideas through heavily symbolic content. The issue with this, for all its strengths along the way, is that the film struggles to justify, or to explore that symbolism; if you were to be uncharitable, you could even suggest that there simply isn’t enough depth here to bring everything together at the end, and it’s thus left to the audience to do it for themselves.

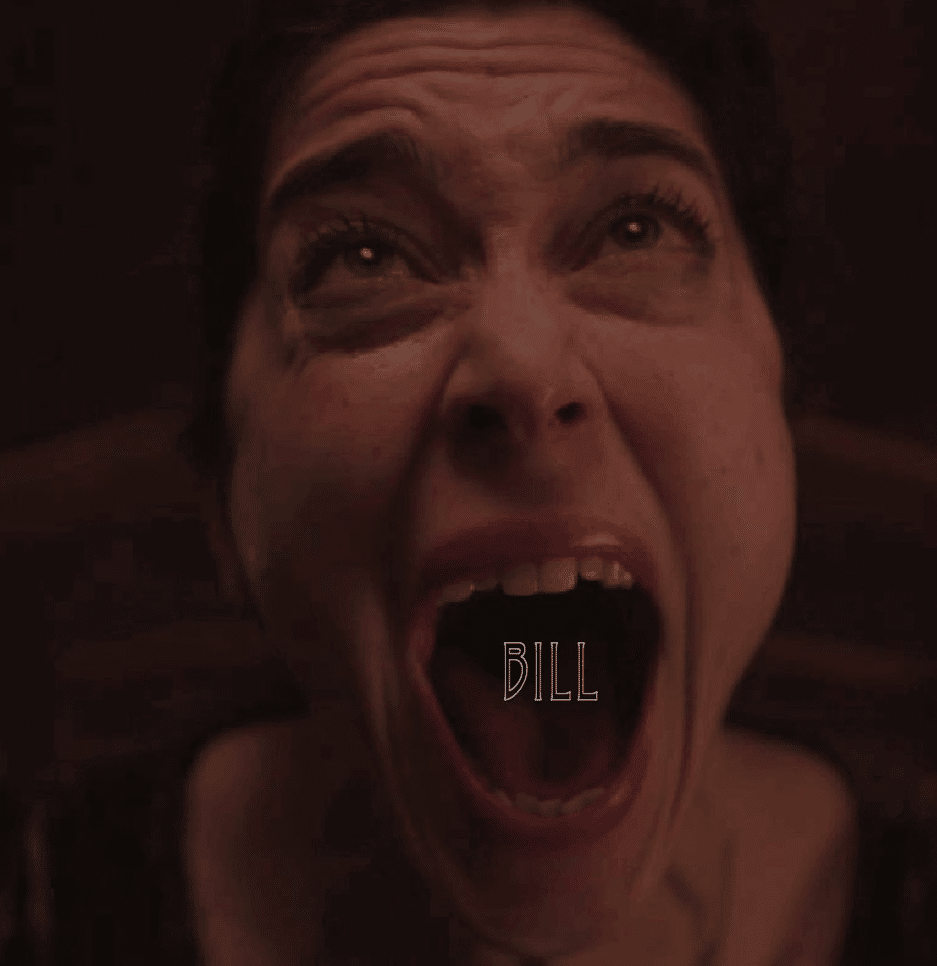

That’s not to say that the film doesn’t start strongly: it absolutely does, weaving an intense sense of dread and vulnerability. This is cemented by the performance of Jessie Buckley as Harper, who immediately comes across as a woman raw with grief after the unexpected death of her husband, James. But grief is seldom uncomplicated; James’s death came after a number of problems for the couple, culminating in Harper’s decision to ask for a divorce. To help get over this ordeal, Harper has rented a house in the remote English countryside. When she arrives, she’s greeted by the owner, Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear) – what we’d tend to call an ‘eccentric’, an old country boy who has lived very much within the village bounds, though he seems harmless, and Harper’s plan to get away from it all seems, initially, to be working. She heads out to explore the area, and the greenery and the silence seem to be working their magic. (Incidentally, let’s assume seeing apples on the trees at the same time as bluebells in the woods is all part of the strange otherworldliness of this place, rather than a daft oversight.)

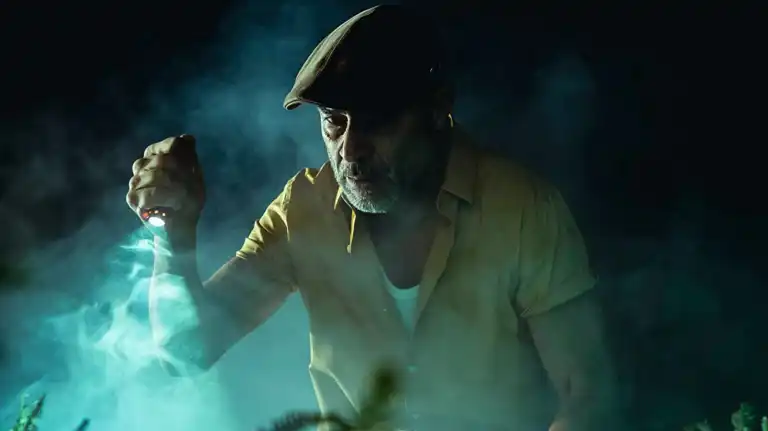

As mentioned above, Men explores its themes through a horror lens, and there’s always a storm after a moment of calm such as this. As Harper playfully tests out the echo of her voice under an old, disused railway arch, she seems to disturb someone: a man at the other end of the tunnel stands up, and then begins to make his way towards her. She responds as anyone would – or at least, as any lone woman socialised from early childhood to steer clear of strange men in lonely locations would. She retreats, but the nude (!) male figure follows her.

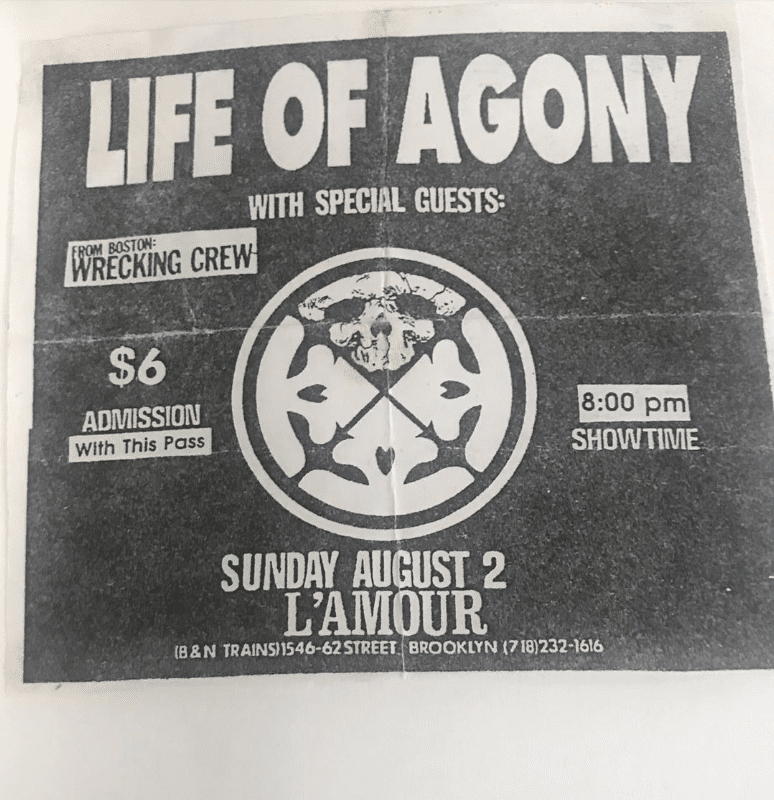

Thus begins the unravelling of whatever binds Harper, even nominally, to reality; this means, in terms of plot coherence, a series of diminishing returns. Not only does this strange, mute man follow her back to the comparative safety of the house, but all of the men she encounters thereafter (all played by Kinnear) display a range of threatening or degrading behaviours towards her. She behaves at first as you may expect, which is to run through the gamut of: attempted politeness, bemusement, anger and fear – pretty much in that order. However, the stranger things get, the less Harper’s reactions resonate with what’s expected, and the looser the relationship between narrative and exposition becomes. The film also introduces some very loaded symbolism and imagery which it values enough to come back to several times, though never quite to the point of unpacking that symbolism. In fact, in its initial setup, Men did remind me a little of Robin Redbreast (1970), story, folk horror symbolism and all.

The difference is that, neither in its dialogue nor its denouement, do these images and motifs get explored in any depth; even if they are aesthetically appealing and shot beautifully, they tantalise at a meaningful conclusion which, sadly, never comes. After becoming engrossed in the ratcheting isolation of a profoundly likeable and sympathetic female lead – and equally impressed by the acting chops of Rory Kinnear, who is an absolute asset to everything he’s ever in – the film withers and dithers away to an ending, which feels disappointing. It feels unfair to everyone concerned in establishing and carrying the film to that point, too; adding in a quick hodgepodge of grotesque surrealism feels like a cop out, not a bold artistic decision. It’s also difficult to determine whether the film is critiquing sexist attitudes, or glorying in regurgitating them somehow; much of this remains unchallenged, or gets blurred by the strong new focus on the ick factor.

Men does many things very well, particularly in its first hour: it’s artistically made, well shot, with a haunting choral soundtrack which perfectly suits the escalating tension on-screen. Its initial confidence is also clear in its early use of playful notes, giving us some moments of dark humour to offset the sense of a true existential crisis in the offing. Sadly, the rather sudden spasm into all-out metaphor (after rather clumsily lining up a few obvious symbolic nods) dispenses with many of the finer points which the film had built. It’s fitting that Kinnear spends a lot of time wandering around in the altogether, as The Emperor’s New Clothes comes to mind at this point. It’s a shame, and though no detriment to the excellent performances, it’s at great detriment to the film as a cogent whole. As I left the cinema, I overheard another attendee say to his friend, ‘I guess I’ll have to Google what that all meant’. That isn’t really the hallmark of a fulfilling trip to the cinema or an effective story, I’d argue.

Men (2022) is in cinemas now.