It never feels like a negative to find there’s a new David Cronenberg film, and with a title and premise like The Shrouds (2024), hopes were bound to be high. Indeed, the main idea here is fascinating, blending Cronenberg’s love for body horror/bodily trauma with a potential source of existential debate, here about life and death itself. There’s no bigger idea to take on. However fascinating it is, though, it doesn’t quite go anywhere. This is a deeply frustrating film. A charitable take on this would be that it’s all deliberate, because grief itself is unending, but I’m not too sure. Every review seems to mention the director’s own bereavement (his wife died in 2017) and clearly, he has brought much of that experience to bear on his most recent project, but the final impression is of a narrative which didn’t quite know how to reconcile the central premise with something more significant. It’s more bosom-y than I’d expect for a film all about grief and loss, too, but we’ll get to that.

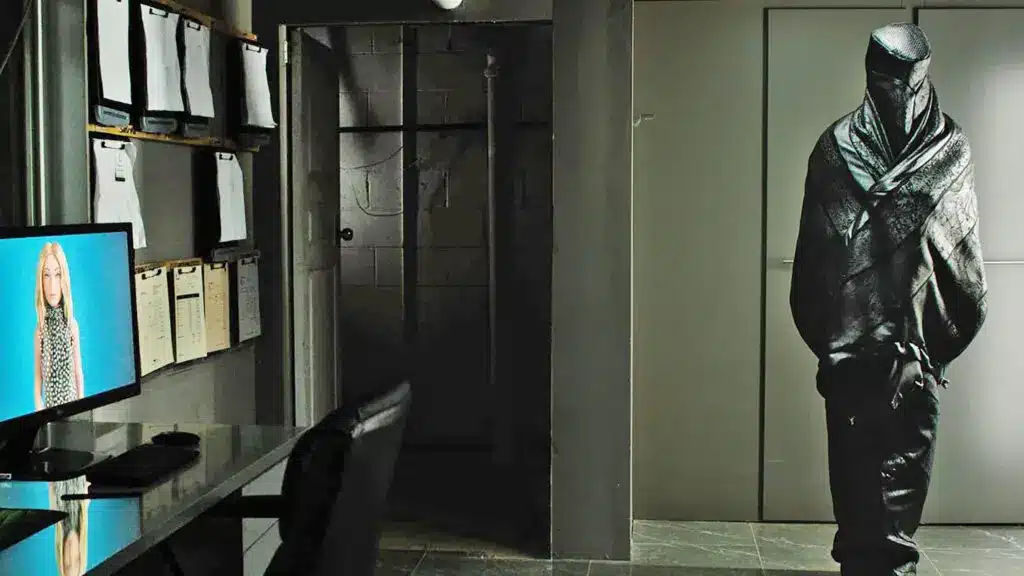

In the film, a somewhat bewildered Vincent Cassel plays Karsh Relikh, an entrepreneur who has revolutionised the relationship with the cemetery. Remember that the cemetery itself was a kind of revolution in how people – from the 19th Century onwards – related to death, offering a new kind of eternal rest beyond the cramped, unhealthy confines of the urban churchyard. The Shrouds – the cemetery itself is named that, because of course it is! – is owned by Karsh, whose big idea has been to integrate technology into the burial experience, so that people can now interface with their buried loved ones, using an app to watch them decay in real time. This has been made possible through a new form of shroud, which connects the body to outside world, scanning it and relaying the images either to phones or to a screen on the tombstone.

Here’s the first issue, as much as I am fully aware that this is a Cronenberg film and yes, this idea fits both with his creative means of seeing the world and his own reported wish when he lost his beloved wife that he, like Karsh, just wanted to lie down in the grave with her, such was the nature of his grief. He’s simply played out this wish here in a very Cronenbergian way, and he’s not the first either; medieval art through to John Keats through to any number of horror titles have pondered the decay process, just as, arguably, so have many of our best-known cinematic monsters. But wanting to patch into the grave in real time to see if grandma’s nose has fallen off or not? It’s a stretch, particularly against the otherwise very normal-seeming world against which the film at least begins to play out. Even the swish Shrouds restaurant doesn’t seem out of the question, as people will dine anywhere which gives them a good story to share, but the tech itself does.

However, given time and space, this could have moved from being an initially absurd, though intriguing, and obviously ghastly idea to being a more integrated one. It’s clear that there are moments meant to trigger an uncomfortable laugh (most of the script triggers the same response, but at first that’s fine, too). Beyond the engaging shock factor of Karsh taking a first date to look at his wife’s now skeletonised remains, however, the tech is used more as a means to justify other, semi-realised plot points. This is a shame, because there are some great scenes, reveals and ideas during the first part of the film. These make you remember that David Cronenberg is in his eighties; it’s a great thing that he’s still pulling projects together, even if they have been wildly variable in quality for quite a few years.

Little wonder we see so little of the shrouds technology working, though. Just as Karsh is on the verge of selling his idea to other countries, there’s an attack on his flagship cemetery: data is stolen, and the stones themselves are badly damaged. Fearing a run of bad publicity, Karsh has to work fast both to repair his cemetery, and to find out who could have done this; what do they want? Are they religious? Environmentalists? Are they grieving and angry? Is it a personal vendetta against him? He wonders if it can have something to do with the odd nodule-type structures he recently noticed on his wife’s bones, during an enjoyable few moments of really getting in there to peer at her skull. Those chilly spring evenings must just fly!

That’s another of the films odd sticking points, though: Karsh’s love for his wife relates to her again and again as a body; his memories of her give way to dreams in which she’s always naked (he doesn’t seem to own a photograph of the woman clothed, either) and a lot of his angst in the here-and-now is to do with his ailing libido. Just when it seems he’s condemned to only ever experience sex in dreams where bits of his wife’s body disappear (or – in the film’s only real shock – break) he manages to bag not one, but two lovers: his wife’s sister Terry (Diane Kruger), who gets hot over conspiracy theories (lucky woman then, these days) and a sight-impaired Korean woman, Soo-Min (Sandrine Holt) whose own techbro partner has no interest in her sexually, because he, too, is chronically ill. There’s a lot of oddly perfunctory sex in this film, and a surfeit of boobs, even though Cassel’s modesty is largely preserved, largely because he’s blocked by boobs.

This is all something of a distraction, this midlife sexual reawakening, as he still needs to find out what the hell has been going on at his cemetery. Luckily he has ex-brother in law and top programmer Maury (Guy Pearce) to help him get to the bottom of it. Maury has also helpfully programmed an AI personal assistant for Karsh too; it goes by the name of Hunny, and yes, the avatar gets nude. It’s that, or it turns into a koala. As Karsh thinks back over his relationship with his wife, he recalls that an old flame of hers actually turned out to be her oncologist when she fell ill. Clear conflict of interests? Nope – Karsh is simply jealous that the doctor in question ‘had her body’ before him. Devoid of any deeper resonances, this just feels reductive in the sense of not knowing where to go with it all. Sex and death can be linked, sure – but is this it?

If that all sounds garbled, then I’m afraid it’s because it is. Eroticised explorations of death (and by extension, mourning) are long established; the role of technology in modern society is often debated in film; any sense of a conspiracy offers the possibility of a mystery. The Shrouds is certainly ambitious and tries to bring all of those together, but not successfully. You can ask an audience to accept one absolutely batshit idea; the rest of the story has to have features and ideas we’d recognise in a world where people can’t gawp at their decomposing loved ones. Hunny (also voiced by Kruger) is a bit of an embarrassment; it makes me think of older relatives who are really pleased they know how to work WhatsApp; technology changes so rapidly, you really need to bring someone in on these kinds of inclusions who can advise whether it’s suitable or not.

Suggestions of bigger forces who want the shroud tech aren’t really delineated or seen through to any sort of a conclusion, but there’s enough said to make the audience wonder: why? Why would anyone want to hack static underground cameras? The technology already exists above ground. That’s not a spoiler, by the way, as it doesn’t really go further than wondering whether competing totalitarian regimes are behind the cemetery attack, and after two hours of rather thin plot development, The Shrouds doesn’t provide satisfying answers, opting instead for a rather glib and confusing ending. It’s a shame, because there are some slivers of promise along the way, and yeah, perhaps seminal filmmakers are held to a harsher account than many others, but sadly this film is just not able to pass muster, whoever made it – or why.

The Shrouds (2024) is on a limited UK cinematic release now.