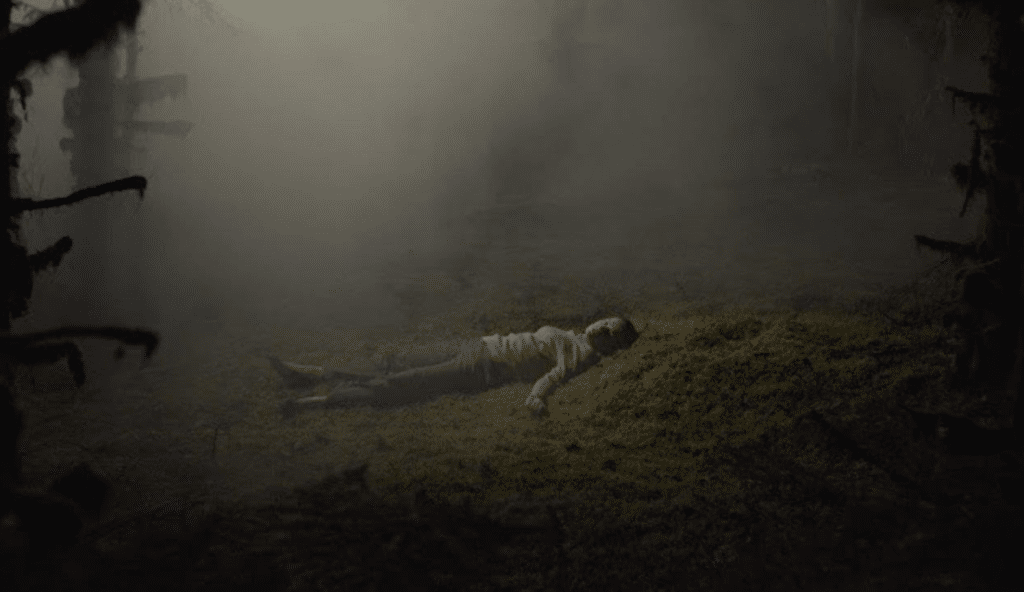

A sylvan nightmare introduces us to the world of Mercy Falls (2023) and a sylvan nightmare it remains; make of that what you will. As a film, it retains all of the standard nonsensical elements of a nightmare, alongside its tension and inescapability. The film on the whole can be perplexing, though it does do enough to remain entertaining.

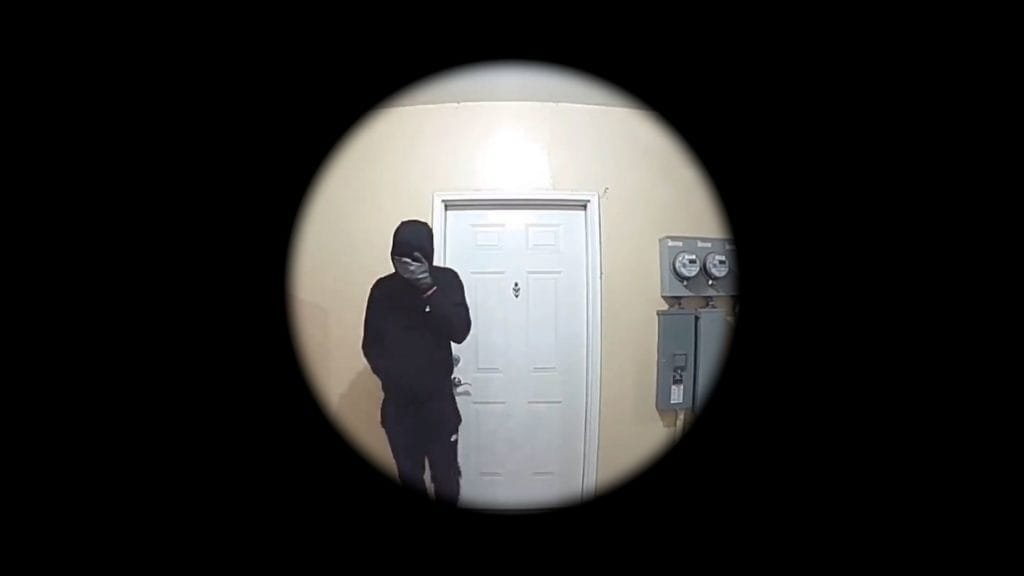

A childhood flashback wakes Rhona (Lauren Lyle), now a young woman off on a camping expedition in the Highlands with a group of friends. They evade the trope of picking up a scary hitchhiker by sensibly speeding past straight them on their way to a rendezvous point, a nearby hotel. Frankly, once I’d seen the girls’ car (emblazoned with flower and ‘peace’ stickers) then all bets were off, but: Rhona has a plan. She wants to hike out to her late father’s old cabin near a place called Mercy Falls; she has a map, a map she clearly struggles to read, but wouldn’t you know, the hitchhiker they passed earlier has also arrived at the hotel. Carla (Nicolette McKeown), aside from having a face of perfect make-up, come what may, is an experienced hiker and offers to help them in their search. Whilst this clearly disrupts the delicate friend group ecosystem as far as Rhona is concerned, the others are more enthusiastic: as such, Carla tags along/takes over, and off they all go.

Whilst the minor questions about what happens next soon conglomerate into bigger questions about people’s motivations and behaviours, at heart the tension here comes from Rhona’s past and Carla’s present, as (and it’s probably not a spoiler to say) she isn’t all she seems. But then again, Carla’s past also turns out to be a factor, and as they get deeper into the remote woodland, the issues between these two young women in particular drive the rest of the events which follow. Childhood misery, budding female antipathy, a few lines in the script which question whether this naïve lot has an emergency plan – here’s our raft of elements, then, which could be explored or exploited in a range of ways.

As we get going, it’s clear that the Scottish landscape is one of the stars of the show, and it’s filmed well; it’s also positive that these are Scottish young people in their own country, which eschews tried-and-tested tension between outsiders and place in a broader sense, something that typically comes with its own issues (although these particular hikers are themselves strangers in this environment; this could be anywhere, albeit without a family cabin somewhere off in the mysterious distance.)

As for the young people themselves, well: the script starts out by painting a picture of some plausibly daft, adrift townies on their way into a dangerous, remote place. That’s all well and good, but the undercurrent of sexual tension here is far more difficult to believe in, and leads the plot down some rather sketchy paths (such as: how on earth do you lose two of your party when there are only six of you and you’re at a tiny campsite?) It’s a bit clumsy and extraneous, even if we allow for the fact that – well – so are people. But other motivations are puzzling too, and should have been clearer, if we are to believe that all of these events unfold between our characters; certain big scenes in the film are utterly mystifying (I shall say only ‘fallen tree’ here and anyone who sees the film will get it completely). It always seems like a good, brutal script edit would iron out so many of the issues which befall low budget indie films, and cost little to no money out of the budget, in the grand scheme of things. There has to be a good answer to the ‘why?’

Still, there’s enough here to keep the film moving along. Credit goes to Lauren Lyle in particular, who is given a lot to do and a lot to carry into the final act; in fact, she offers the most nuanced performance throughout, and deserves recognition for that. If you can let your eyes glaze over at some of the rookie errors, then you just might find enough to enjoy in the often baffling melee.

Mercy Falls (2023) received a UK theatrical release on 29th August 2023. Mercy Falls is in cinemas now and on digital from 6th November.