I’ll be the first to admit that I’m woefully ignorant of the diverse cinema of the former Soviet Union; this goes even for those filmmakers who bridged that East/West divide, such as the best-known of the bunch, I’d say, Andrei Tarkovsky. Stalker (1979) is the first of his films that I’ve ever seen and, yep, I’m afraid that goes for Solaris too. Now, as to whether Stalker is the best starting point remains to be seen; it’s certainly a challenging film, and I can’t help but think that the ‘sci-fi’ tag attached to it may do it a disservice in some respects. When we think of science fiction, we think of the visible presence of the improbable. In Tarkovsky’s work, the improbable is there as context only, and there are no flashy effects or plot developments after the framework is established.

The film begins in a dank, dour apartment with a family – father, mother and child – sharing one bed. Medicines and syringes adorn a nearby table. Dad (Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy) is looking with affection upon his sleeping daughter, but relations between him and his wife seem strained, to say the least: he tries to sneak away, presumably for some sort of employment, but Zhena (Alisa Freindlikh) is angry, doesn’t want him to leave and winds up inconsolably weeping on the floor. It turns out that his employment is that of a ‘stalker’. These people lead others into a mysterious part of the landscape known as the Zone. The Zone simply…appeared one day: some believe that it was the result of an asteroid, some say it was the work of some sort of extraterrestrial intelligence. Soldiers sent to this region disappeared and so, to try to safeguard others, the authorities erected a guarded cordon around it, making it intensely dangerous for anyone to sneak in. Stalkers help people get in – and they do so because it transpires that within the Zone, there exists the potential to make one’s heart’s desires come true.

Together with two other men – known only as ‘The Professor’ and ‘The Writer’ – the stalker takes them through deserted, waterlogged streets and nearer to their destination, avoiding gunfire along the way. The further they go, the more the landscape seems to be post-apocalyptic in some way; everything is broken, or derelict. Absolutely everything is flooded. The route is dangerous, they are low on resources and the soldiers keep up their assault on them, but eventually, they are able to reach the outskirts of the Zone.

Together with two other men – known only as ‘The Professor’ and ‘The Writer’ – the stalker takes them through deserted, waterlogged streets and nearer to their destination, avoiding gunfire along the way. The further they go, the more the landscape seems to be post-apocalyptic in some way; everything is broken, or derelict. Absolutely everything is flooded. The route is dangerous, they are low on resources and the soldiers keep up their assault on them, but eventually, they are able to reach the outskirts of the Zone.

Here, the palette changes from sepia to colour. This new area is a lush, but still a war-scarred place, and the stalker insists that they cannot simply walk straight to their destination – somewhere known as the Room. He tells the two others that the whole place is rigged with traps to keep people away, and that they must tread very, very carefully. Many people have, he insists, perished, right on the threshold of the Room. They must go cautiously, and they must also wait, and wait, for the right time to move on.

These three men – although acquaintances at best, rather than friends – spend a great deal of the rest of the film philosophising and pondering just what it is that they want from this ‘Room’. This futile hankering after something unknown has nothing in common with any of the sci-fi I could mention; if anything, this is Waiting for Godot with a science fiction back-story. It’s also similar to Godot in that these similarly, broken, shabby men are hanging around waiting for something which is a possible means through dissatisfaction and hardship, but they don’t really know what this relief will look like when they find it. And, as they don’t know what it looks like, they don’t really know how to progress. Stalker is incredibly oblique, and although there is some intimation of a tricksy intelligence which is keeping them all from what they want, this film is otherwise a long digression on the meaning of life which will, I am sure, test the patience of many viewers. I’d say you would need to have your appreciation of art-house in the ascendant, far more so than any lingering love for sci-fi or indeed any other genre, in order to enjoy this film (which, at a testing two hours forty minutes, may turn out to be rather important…)

Being art-house orientated, Stalker successfully looks very striking indeed, positioning its characters against abandoned places and post-War bunkers (the film was shot on location in Russia and Estonia, each of which still bore the marks of conflict, even in the 1970s.) It also boasts a painterly approach, with lingering shots, creative uses of colour and a camera which deviates from the inner turmoil of the three men to pan over interesting, and clearly composed tableaux of potentially symbolic objects. Stalker is massively lo-fi, however, with an emphasis on rather cerebral dialogue about ‘the meaning of it all’ and an appropriately obtuse Soviet conclusion where we learn only not to ask again in future. La La Land, this categorically ain’t.

Being art-house orientated, Stalker successfully looks very striking indeed, positioning its characters against abandoned places and post-War bunkers (the film was shot on location in Russia and Estonia, each of which still bore the marks of conflict, even in the 1970s.) It also boasts a painterly approach, with lingering shots, creative uses of colour and a camera which deviates from the inner turmoil of the three men to pan over interesting, and clearly composed tableaux of potentially symbolic objects. Stalker is massively lo-fi, however, with an emphasis on rather cerebral dialogue about ‘the meaning of it all’ and an appropriately obtuse Soviet conclusion where we learn only not to ask again in future. La La Land, this categorically ain’t.

So – as a first expedition with Tarkovsky, this was admittedly a challenge for me. Stalker is a strange, hypnotic and well-soundscaped creative enterprise, for sure, as well as being quite unlike anything else I’ve seen (apart from, as mentioned, a certain play by a certain Beckett) but it’s also dreary and motionless for much of the time, a chance to peer through the undergrowth and dereliction at some troubled souls without really being able to see any of them through their plight. I guess this is kind of the point. Should you wish to pick this one up, then, the Criterion Collection are about to issue a special edition which boasts a new digital restoration and a crop of special features.

Stalker will be released on 24th July 2017.

I will say I was rather surprised to see that The Beguiled had been remade. Not frothing-at-the-mouth indignant that anyone could ever remake such a film, but more intrigued that anyone would want to do it: the 1971 original, starring Clint Eastwood, was a strange project which probably didn’t find its audience upon release and it’s struggled to get due recognition since. It’s not a romance, and it’s not a war film, it’s incredibly tense, but it’s low on action. These trope-defying films have a hard time and they’re a hard sell. So why return to the subject matter all over again?

I will say I was rather surprised to see that The Beguiled had been remade. Not frothing-at-the-mouth indignant that anyone could ever remake such a film, but more intrigued that anyone would want to do it: the 1971 original, starring Clint Eastwood, was a strange project which probably didn’t find its audience upon release and it’s struggled to get due recognition since. It’s not a romance, and it’s not a war film, it’s incredibly tense, but it’s low on action. These trope-defying films have a hard time and they’re a hard sell. So why return to the subject matter all over again? Having no great moral impetus – beyond hard cash – to get back to the battle, he sets his morals aside completely, happy to manipulate each of the women for – is it his own vanity? For sport? Or simply to secure their Southern hospitality for as long as possible? It seems that it’s any or all of those reasons in turn, but what’s certain is that the power shifts in The Beguiled move one way, then another, like a needle and thread through a tapestry (or any of the other less orthodox fabrics we see when we encounter this women’s work in the film). First McBurney is powerless – completely prone, after his injury, and the women who tend to him seem to enjoy his powerlessness: Miss Martha cleaning his (almost) naked body is turned into a queasily erotic tableau where a man potentially about to die of his injuries becomes some serious eye candy: furthermore, the enjoyment she gains from looking at him and touching him is ratcheted up by the use of microphones which pick up the rapid changes to her breathing, a trick the film employs elsewhere with the other women. Then, McBurney takes full stock of his situation, flattering and cajoling the women – particularly Miss Edwina, who Dunst effectively plays here as a living powder-keg. She’s an insular and downbeat character (teaching will do that to you) but her emotions reflexively spark into life when it transpires that she’s been lied to. Thus, the power shifts again, and again after that.

Having no great moral impetus – beyond hard cash – to get back to the battle, he sets his morals aside completely, happy to manipulate each of the women for – is it his own vanity? For sport? Or simply to secure their Southern hospitality for as long as possible? It seems that it’s any or all of those reasons in turn, but what’s certain is that the power shifts in The Beguiled move one way, then another, like a needle and thread through a tapestry (or any of the other less orthodox fabrics we see when we encounter this women’s work in the film). First McBurney is powerless – completely prone, after his injury, and the women who tend to him seem to enjoy his powerlessness: Miss Martha cleaning his (almost) naked body is turned into a queasily erotic tableau where a man potentially about to die of his injuries becomes some serious eye candy: furthermore, the enjoyment she gains from looking at him and touching him is ratcheted up by the use of microphones which pick up the rapid changes to her breathing, a trick the film employs elsewhere with the other women. Then, McBurney takes full stock of his situation, flattering and cajoling the women – particularly Miss Edwina, who Dunst effectively plays here as a living powder-keg. She’s an insular and downbeat character (teaching will do that to you) but her emotions reflexively spark into life when it transpires that she’s been lied to. Thus, the power shifts again, and again after that. A return to the zombie genre later in his career lacked the verve and the impact of his earlier work, with his later films Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead never attaining the same organic sense of social commentary, but people were delighted to see him working again after such a long hiatus. Still, it’d be incorrect to see him solely as ‘the zombie guy’ anyway, and would do him a disservice. The Crazies – which pre-dates Dawn of the Dead – is a great, manic film, and the underrated (and very subtle) vampire horror of Martin is a whole world away from the zombie genre. Whilst Romero’s filmography isn’t vast, he made enough films to show that he could indeed be versatile.

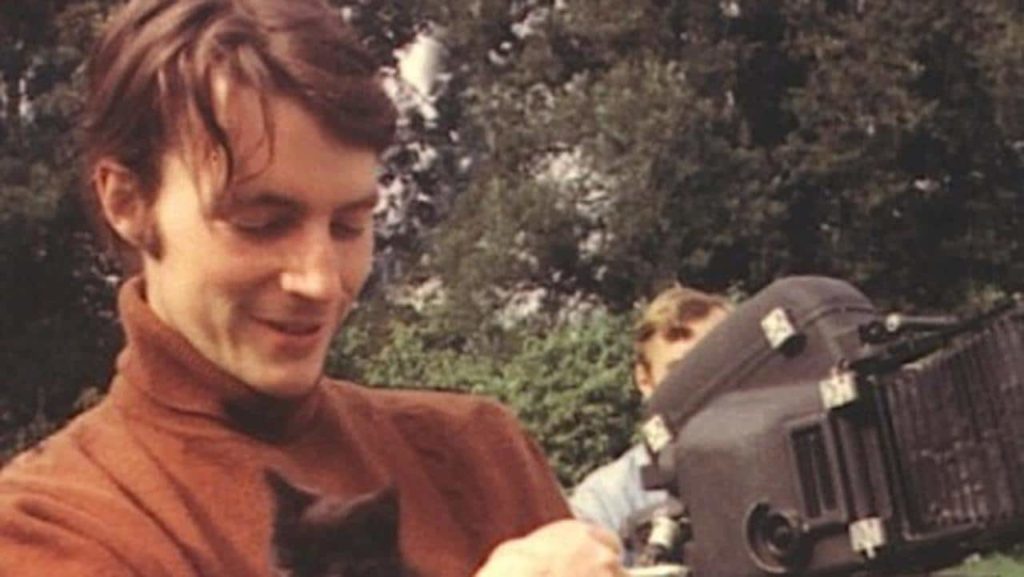

A return to the zombie genre later in his career lacked the verve and the impact of his earlier work, with his later films Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead and Survival of the Dead never attaining the same organic sense of social commentary, but people were delighted to see him working again after such a long hiatus. Still, it’d be incorrect to see him solely as ‘the zombie guy’ anyway, and would do him a disservice. The Crazies – which pre-dates Dawn of the Dead – is a great, manic film, and the underrated (and very subtle) vampire horror of Martin is a whole world away from the zombie genre. Whilst Romero’s filmography isn’t vast, he made enough films to show that he could indeed be versatile. Personally, out of the entire publication, I most enjoyed Jon Towlson’s feature on British director Michael Reeves. Reeves, who directed two phenomenal films (The Sorcerers and Witchfinder General) died as a very young man following an overdose. Towlson’s feature focuses on the psychogeography of Reeves’ life, looking at the homes and pubs which were not only close to his heart, but probably integral to how he lived. These spaces were where he socialised, threw ideas around and – towards the end – grappled with what he saw as the deeply wrongheaded criticisms of his work, particularly the then much-maligned Witchfinder General, now considered a classic of its genre. It’s an interesting perspective, looking squarely at the seeming incongruity between Reeves’ films and his surroundings but always remaining sympathetic and engaged. It’s hard to disagree with the conclusion of this piece – that the death of Michael Reeves so very young was a phenomenal loss.

Personally, out of the entire publication, I most enjoyed Jon Towlson’s feature on British director Michael Reeves. Reeves, who directed two phenomenal films (The Sorcerers and Witchfinder General) died as a very young man following an overdose. Towlson’s feature focuses on the psychogeography of Reeves’ life, looking at the homes and pubs which were not only close to his heart, but probably integral to how he lived. These spaces were where he socialised, threw ideas around and – towards the end – grappled with what he saw as the deeply wrongheaded criticisms of his work, particularly the then much-maligned Witchfinder General, now considered a classic of its genre. It’s an interesting perspective, looking squarely at the seeming incongruity between Reeves’ films and his surroundings but always remaining sympathetic and engaged. It’s hard to disagree with the conclusion of this piece – that the death of Michael Reeves so very young was a phenomenal loss. Exquisite Terror doesn’t seem to have an overarching editorial policy, meaning there’s no impetus to toe a line, one way or another. This boosts the variety of features on offer – a good thing – though of course it also means that I, like anyone else, will always prefer some articles to others. God Bless America: Stephen King’s Shining by Jim Reader comes to mind here I’m afraid: there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with how this piece is written, as it flows well, but the claims it makes about Kubrick’s seminal horror film seem based on very tenuous evidence. These feel like pre-existing tenuous claims, too, as many improbable interpretations of The Shining already featured in the frankly bonkers documentary film Room 237 (2012), which at the very least made me wonder what it is in particular about The Shining that bears such strange fruit. The premise – that Kubrick’s film is a commentary on the historical treatment of Native Americans, based on two lines of dialogue and some incidental images of Native Americans – is no more convincing now that I encounter it for the second time here. On a similar note, Once Bitten: The Queerness of Becoming Other ostensibly features a ‘queering’ of a handful of werewolf films, but what’s counted as lycanthropic in nature seems a little broad. Also, to my eye, some of the interpretation seems somewhat awry (I don’t know Der Samurai, but one of the key scenes mentioned as evidence of the links between queerness/othering seems to have firm markers of hetero-, rather than homo-erotic lust.) Finally, if you say that werewolf films reflect the anxieties about the AIDS panic of the 80s, then I think we need specific examples.

Exquisite Terror doesn’t seem to have an overarching editorial policy, meaning there’s no impetus to toe a line, one way or another. This boosts the variety of features on offer – a good thing – though of course it also means that I, like anyone else, will always prefer some articles to others. God Bless America: Stephen King’s Shining by Jim Reader comes to mind here I’m afraid: there’s nothing whatsoever wrong with how this piece is written, as it flows well, but the claims it makes about Kubrick’s seminal horror film seem based on very tenuous evidence. These feel like pre-existing tenuous claims, too, as many improbable interpretations of The Shining already featured in the frankly bonkers documentary film Room 237 (2012), which at the very least made me wonder what it is in particular about The Shining that bears such strange fruit. The premise – that Kubrick’s film is a commentary on the historical treatment of Native Americans, based on two lines of dialogue and some incidental images of Native Americans – is no more convincing now that I encounter it for the second time here. On a similar note, Once Bitten: The Queerness of Becoming Other ostensibly features a ‘queering’ of a handful of werewolf films, but what’s counted as lycanthropic in nature seems a little broad. Also, to my eye, some of the interpretation seems somewhat awry (I don’t know Der Samurai, but one of the key scenes mentioned as evidence of the links between queerness/othering seems to have firm markers of hetero-, rather than homo-erotic lust.) Finally, if you say that werewolf films reflect the anxieties about the AIDS panic of the 80s, then I think we need specific examples. For someone not given to supernatural beliefs, I have a fascination with supernatural horror, and there are few supernatural horrors more famous than The Amityville Horror; close to forty years after it first appeared, there are still films getting made which carry the Amityville moniker. One of the key reasons for the success of the original film was the link between the screenplay and the ostensibly ‘true story’ of the Lutz family, whose experiences are dramatised in the film. The Lutz haunting is itself well known, and a fascinating, terrifying story in its own right, comprising a bizarre blend of testimony from the family themselves and a host of others who had become involved with them, such as the self-styled ‘demonologists’ Ed and Lorraine Warren, whose case films have incidentally turned up elsewhere in horror cinema – such as in The Conjuring (2013) and Annabelle (2014). Any description of a haunting as ferocious as the one recounted by the Lutz family always seems to me to be a detective story, too: people corroborate or contradict one another, recount or re-assert what they experienced. Still, the film itself doesn’t much trouble with these ambiguities, preferring to play out many of the events described by the Lutzes on screen, in as straightforward a way as you can muster when those events include inexplicable phenomena.

For someone not given to supernatural beliefs, I have a fascination with supernatural horror, and there are few supernatural horrors more famous than The Amityville Horror; close to forty years after it first appeared, there are still films getting made which carry the Amityville moniker. One of the key reasons for the success of the original film was the link between the screenplay and the ostensibly ‘true story’ of the Lutz family, whose experiences are dramatised in the film. The Lutz haunting is itself well known, and a fascinating, terrifying story in its own right, comprising a bizarre blend of testimony from the family themselves and a host of others who had become involved with them, such as the self-styled ‘demonologists’ Ed and Lorraine Warren, whose case films have incidentally turned up elsewhere in horror cinema – such as in The Conjuring (2013) and Annabelle (2014). Any description of a haunting as ferocious as the one recounted by the Lutz family always seems to me to be a detective story, too: people corroborate or contradict one another, recount or re-assert what they experienced. Still, the film itself doesn’t much trouble with these ambiguities, preferring to play out many of the events described by the Lutzes on screen, in as straightforward a way as you can muster when those events include inexplicable phenomena. …And there are some successful elements – the ‘red eyes’ scene still works well, for instance – enough so, that the film has enjoyed great influence on other horror films which have followed in its wake. The impact of these key scenes is always increased, for me, when you remember that an adamant family was convinced that these phenomena were real – enough so that they eventually fled the house, leaving all of their belongings there, even leaving food on the table. The whole ‘based on a true story’ preamble, which we’re so used to now, owes much to the success of Stuart Rosenberg’s movie, as does the ‘real time’ unfolding of events, a technique still integral to many scare stories (it’s relevant to note that much ghostly ‘found footage’ embeds real time via its shooting style.) Sure, there’s some back-and-forth between banality and histrionics, but The Amityville Horror is an important chapter in the genre and is worth a place in your collection.

…And there are some successful elements – the ‘red eyes’ scene still works well, for instance – enough so, that the film has enjoyed great influence on other horror films which have followed in its wake. The impact of these key scenes is always increased, for me, when you remember that an adamant family was convinced that these phenomena were real – enough so that they eventually fled the house, leaving all of their belongings there, even leaving food on the table. The whole ‘based on a true story’ preamble, which we’re so used to now, owes much to the success of Stuart Rosenberg’s movie, as does the ‘real time’ unfolding of events, a technique still integral to many scare stories (it’s relevant to note that much ghostly ‘found footage’ embeds real time via its shooting style.) Sure, there’s some back-and-forth between banality and histrionics, but The Amityville Horror is an important chapter in the genre and is worth a place in your collection. For many people, horror films wouldn’t be the obvious choice if they wanted to feel in some ways uplifted. Horror isn’t about feeling good, after all – or at least, that’s not the usual verdict. It’s about feeling scared. Many people would perhaps be more likely to go for a period drama, a musical, a romantic comedy, or something of that kind: the type of film where, when it comes down to it, everyone eventually settles for something or someone and lives ‘happily ever after’. That’s the more normal thing to help a person relax, and probably the last thing which would pick me up.

For many people, horror films wouldn’t be the obvious choice if they wanted to feel in some ways uplifted. Horror isn’t about feeling good, after all – or at least, that’s not the usual verdict. It’s about feeling scared. Many people would perhaps be more likely to go for a period drama, a musical, a romantic comedy, or something of that kind: the type of film where, when it comes down to it, everyone eventually settles for something or someone and lives ‘happily ever after’. That’s the more normal thing to help a person relax, and probably the last thing which would pick me up. The recent return of Twin Peaks has meant a wonderful thing: David Lynch is back on our screens again, and even in the short time since my recent retrospective piece on

The recent return of Twin Peaks has meant a wonderful thing: David Lynch is back on our screens again, and even in the short time since my recent retrospective piece on  The Alien franchise has been around for the same amount of time as I have, and it’s fair to say that (alongside many other people roughly the same age as me, no doubt) the alien creatures of its universe still feel as ingenious and horrifying now as they ever did, having been around in our peripheral vision for so long. I’m not one of those people who maligns Aliens 3 or indeed Alien: Resurrection, either – I think that they are each, in their way, compelling further chapters in the mythos – but, when it turned out that Ridley Scott was coming back to add a prequel to this story, it was exciting news. The resulting piece of work, Prometheus (2012) is undoubtedly an attractive film, with meticulous photography and striking visuals throughout, but its plot is sadly garbled, and it contains a series of unforgivable plot holes which are large enough to lose a ship in. After so many years of waiting and wondering about where the xenomorphs had come from, it didn’t feel as though we were any further ahead by the time the titles rolled – in fact, many viewers had more unanswered questions than ever, even taking into account the general murmur which said that this was NOT an Alien film, and shouldn’t be treated as such. So, what about all those questions then? Turns out Ridley Scott didn’t intend Prometheus to be a stand-alone prequel, and he was working on another prequel – this time a film which picks up a decade in time after the loss of the Prometheus.

The Alien franchise has been around for the same amount of time as I have, and it’s fair to say that (alongside many other people roughly the same age as me, no doubt) the alien creatures of its universe still feel as ingenious and horrifying now as they ever did, having been around in our peripheral vision for so long. I’m not one of those people who maligns Aliens 3 or indeed Alien: Resurrection, either – I think that they are each, in their way, compelling further chapters in the mythos – but, when it turned out that Ridley Scott was coming back to add a prequel to this story, it was exciting news. The resulting piece of work, Prometheus (2012) is undoubtedly an attractive film, with meticulous photography and striking visuals throughout, but its plot is sadly garbled, and it contains a series of unforgivable plot holes which are large enough to lose a ship in. After so many years of waiting and wondering about where the xenomorphs had come from, it didn’t feel as though we were any further ahead by the time the titles rolled – in fact, many viewers had more unanswered questions than ever, even taking into account the general murmur which said that this was NOT an Alien film, and shouldn’t be treated as such. So, what about all those questions then? Turns out Ridley Scott didn’t intend Prometheus to be a stand-alone prequel, and he was working on another prequel – this time a film which picks up a decade in time after the loss of the Prometheus.