An ancient curse, probably Chinese in origin, ran something like this: ‘May you live in interesting times’. It’s a wry old phrase. The insinuation is that when things get interesting, then it’s often a useful code for bad news, so via a play on meanings, and without saying so outright, it’s a hex that seethes with its true intent. Subtle, veiled…so it probably wouldn’t generate a Twitter storm or begin the only process which now seems to matter – breaking the internet.

An ancient curse, probably Chinese in origin, ran something like this: ‘May you live in interesting times’. It’s a wry old phrase. The insinuation is that when things get interesting, then it’s often a useful code for bad news, so via a play on meanings, and without saying so outright, it’s a hex that seethes with its true intent. Subtle, veiled…so it probably wouldn’t generate a Twitter storm or begin the only process which now seems to matter – breaking the internet.

We live in times whereby what’s ‘interesting’ hinges almost entirely on taking an approach which is deliberately simplistic, contrary, and – intentionally or otherwise – often misrepresents something of the topic at hand, allowing a flood of corrections from people who feel all warm and glad inside to be able to say so. This is the sort of thing which now dominates; a pinch of bullishness, a determination to find a new angle and a fight to get it recognised. This process has become known as the ‘hot take’; it happens fast, it happens often and it’s largely to the detriment of debate of any kind – in my humble, and not-so-novel opinion, of course.

As a fan writer, I’ve always tried hard not to get embroiled in the versions of this which spill over into film fandom. But, as someone who also uses Twitter, I do though sometimes pick up on whatever novel approach has just been grafted onto cinema by new commentators who arrive, amazed, to discover that films made fifty years ago on occasion display the opinions and attitudes of their own social milieu, or, those who hit on an unpopular mindset and realise enough to know that they can sail it on a ship to some sort of minor fame. With the former approach, I always find myself thinking of another idiom – that a little learning goes a long way. Well, now it can be #trending a few hours after it issues forth, particularly if it segues with something else which is currently exercising the masses. For the latter, it takes a little resilience, as they’ll in turn get pulled apart, examined and discussed in a number of new hot takes, but it can get the debate going! Everyone will know them! And yeah, I’m aware of the weak irony of using an editorial piece, like this one, to state a contrary opinion about a modern trend, like this one. More and more, though, having anyone read your work depends solely on whether or not you have ‘an angle’. We apparently don’t have time to digest anything without ‘an angle’. The ‘hot take’ has fundamentally reshaped the way we write and the way we read today.

I’m not an idiot, or at least I hope I’m not. I can see how it works. Over the past…god, thirteen years or so that I’ve been uploading articles and reviews onto the Information Superhighway, on my own behalf or via sites belonging to others, it’s never been the case that any of my pieces have in any way ‘gone viral’. It very soon became apparent to me that very few people were ever reading, and this is the case to this day: thankfully, if that’s the right way to put it, I’ve never depended on writing for any sort of an income as I have a job which pays the bills with some spare; had I needed writing for anything other than a hobby, then who knows? This may have shifted the sands, changed how – or if – I wrote at all. I hope I wouldn’t have become a member of the Comment Police, and I hope I wouldn’t have spent my time doing the impossible – trying to change people’s minds or prove them wrong, to no purpose other than a flicker of personal gratification that I Turned Out To Be Right.

But I love writing, and it’s a hobby I’ve had since childhood. I love cinema too, so it makes perfect sense for me to write openly and honestly about films. On occasion, this has pitched my opinions very much against the rest of the ‘horror community’, and we have joked about our contrary natures here at the site for years. But it’s not a tactic; it’s not what we do to generate site traffic. If it was, then we’d have a hell of a lot more people stopping by than we do. No one can ever write entirely free from whatever buzz or hype is happening, sure, but, largely speaking, Warped Perspective’s writers try to steer around it as far as possible. A minimalist approach is the best way, in my book: find out enough about a new project via the channels we’ve come to depend on, but back away from other people’s reviews to get to the film intact and with an open mind. We want to be honest, and we want to write honestly about what we think. I think that’s fair.

Now, if I wanted to send the internet into a wobbler, then a crude attempt to draw people in would stand a far better chance than a lot of my more honest ramblings. Let’s take an example; and before anyone delightedly leaps all over this, it is not an example I happen to believe. But if I were to hack out a piece entitled ‘REASONS WHY JOHN CARPENTER IS A LOUSY DIRECTOR’, with a bit of judicious promoting, people would read it. They’d hate it, but they’d read it. People would ‘Quote Tweet’ and add some hyperbole about how I was a clown who clearly didn’t know how to appreciate the bleak wonder of The Thing (1982). The retweets could be retweeted. Eventually, someone would chip in to say I didn’t go far enough, and that Carpenter’s actually worse, he’s a [insert unpleasant and socially damning label here]. It would rumble on for a while, and enough people – even if a handful at first – would remember Warped Perspective, and be primed for my next piece, DARIO ARGENTO: A REAL LIFE DANGER TO WOMEN? It would only take a little, a very little imagination and a modicum of knowledge to do this sort of thing, and I maintain that there are many people out there who take this approach as a matter of course. It’s their modus operandi, no doubt aided and abetted by editors who want to get themselves on the map by any means and treat their writers as useful idiots.

So, is this the point of writing now? If you write an article and no one either feverishly agrees or ‘calls you out’ for being a bozo, then is it really an article at all? Some would undoubtedly say – no, not really. For my part, this is a tricky one for me because – although as I’ve acknowledged the numbers of people who read my work are small in comparison to many, many sites out there – some part of me is narcissistic enough to want them to be read. There’s no other reason for posting them where people can see them. I have notepads at home; I write my reviews here.

What I actually want from this process is harder for me to identify. On some reflection, I think a lot of my motivation is authentically just to share my enthusiasms, and on occasion, to vent my frustrations, because writing can be cathartic, too. Do I enjoy it when people respond to my writing? To an extent I do, yeah. I’ll maintain that I never deliberately court controversy, but speaking honestly, it can feel disheartening when pieces you felt proud of simply disappear into the ether, and people you feel would have enjoyed them will probably never, ever read them. I think maybe that’s it: the feeling of involvement, of adding to discourse about a beloved subject in even a small way. The way in which I part company so sharply with what counts as ‘debate’ today therefore relates to the nature of that debate; what people call a discussion is often nothing more than a tally of likes, and these can be mutually exclusive things. It’s not looking likely that we’ll ever generate the sorts of hits which would qualify us for Rotten Tomatoes here, then. But a glad word from a new director or a friendly comment from a reader feels an awful lot like it has more substance.

So, the curse of these ‘interesting times’ seems to be that what we deem worthy of notice nowadays has perhaps used invidious means to get there. We probably shouldn’t be too surprised, given that far more significant things than fan writing now live and die by social media (like, ahem, world politics) and very likely this article itself will reside in the TL;DR category. If you’re with me so far, though, we could start to deprive these features of the oxygen of assumed publicity. We could start to resist the pull of the clickbait, if we haven’t already. And as for writers, if you’re ever asked ‘what’s your angle?’ try to take a step back. None of us write in a vacuum, but hopefully we still have sight of our own impressions and ideas, and I wish that the world of online writing was more honest than this pitiable thing we’ve distilled it into. Surely, there’s still more to life – and what we like doing – than ‘likes’.

The Devil’s Advocates series is a collection of slim but studious volumes examining notable horror cinema: here, author Marisa C. Hayes takes us through an intimate, authoritative and long-overdue study of director Takashi Shimizu’s 2002 film. As Hayes notes, whilst Ju-on: The Grudge had a huge impact, it still gets less consideration in print than, for example, Ring. Placing the film at the heart of the rise of what’s known as ‘J-Horror’ here, Hayes builds a solid and readable case, showing how Ju-on both belongs to, and revitalises a tradition of ghost stories.

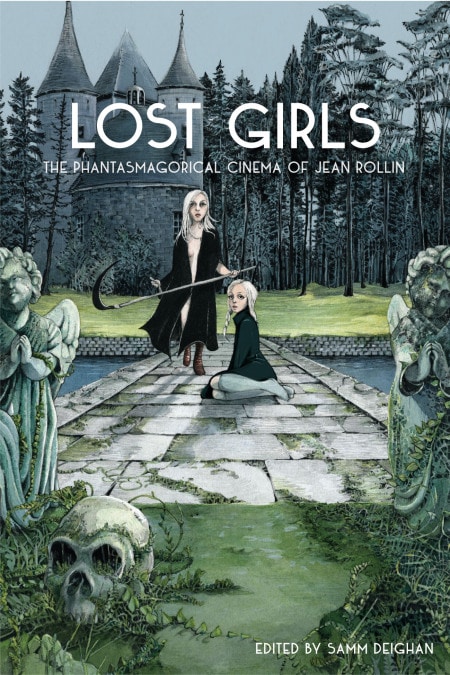

The Devil’s Advocates series is a collection of slim but studious volumes examining notable horror cinema: here, author Marisa C. Hayes takes us through an intimate, authoritative and long-overdue study of director Takashi Shimizu’s 2002 film. As Hayes notes, whilst Ju-on: The Grudge had a huge impact, it still gets less consideration in print than, for example, Ring. Placing the film at the heart of the rise of what’s known as ‘J-Horror’ here, Hayes builds a solid and readable case, showing how Ju-on both belongs to, and revitalises a tradition of ghost stories. I first encountered the cinema of Jean Rollin via the UK’s Redemption Films, whose founder, Nigel Wingrove, became good friends with Rollin over the years; the film company deserves far more awareness of the great service they did by bringing so many of these films into the common consciousness in the Nineties, making the films themselves into an artefact worth having with an array of stylish, distinctive video covers marking them out. Until that time, any knowledge I had of the director’s work came via still images in magazines, and there it probably would have stayed until, in all likelihood, the films resurfaced – though probably not as well-presented – during the earlier years of the DVD revolution, when there was a real surge of hitherto-unknown releases. But however the films may or may not have made their way to our shelves, it’s taken some time for Rollin criticism to follow in print, although Immoral Tales first re-assessed Rollin’s work in the nineties, and more recently, David Hinds published his Fascination: the Celluloid Dreams of Jean Rollin. But is there more to say?

I first encountered the cinema of Jean Rollin via the UK’s Redemption Films, whose founder, Nigel Wingrove, became good friends with Rollin over the years; the film company deserves far more awareness of the great service they did by bringing so many of these films into the common consciousness in the Nineties, making the films themselves into an artefact worth having with an array of stylish, distinctive video covers marking them out. Until that time, any knowledge I had of the director’s work came via still images in magazines, and there it probably would have stayed until, in all likelihood, the films resurfaced – though probably not as well-presented – during the earlier years of the DVD revolution, when there was a real surge of hitherto-unknown releases. But however the films may or may not have made their way to our shelves, it’s taken some time for Rollin criticism to follow in print, although Immoral Tales first re-assessed Rollin’s work in the nineties, and more recently, David Hinds published his Fascination: the Celluloid Dreams of Jean Rollin. But is there more to say? Vampirism is something monstrous, something impossible, but it’s a broad enough kind of monstrosity to mean it can be explored in a number of ways on screen. Unto Death, by director Jamie Hooper, uses the vampirism theme to explore a relationship, and how it is put under extraordinary pressure by the most extraordinary of circumstances. The resulting film is a subtle, but affecting piece of human drama.

Vampirism is something monstrous, something impossible, but it’s a broad enough kind of monstrosity to mean it can be explored in a number of ways on screen. Unto Death, by director Jamie Hooper, uses the vampirism theme to explore a relationship, and how it is put under extraordinary pressure by the most extraordinary of circumstances. The resulting film is a subtle, but affecting piece of human drama.

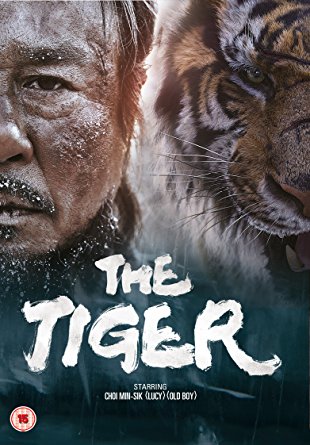

Sometimes a film self-consciously goes for the ‘epic’ tag, and it’s clear from the very outset that this is the case with Park Hoon-jung’s 2015 movie The Tiger. With its sweeping Korean vistas, Sturm und Drang musical score and lone figure set against an unforgiving world it clearly fits the bill, and actually that’s just fine: it’s a genre which seems to suit actor Choi Min-sik, perhaps best known for his work in the groundbreaking Oldboy (2005) which was in many ways an ordeal horror epic, when you think of it now, a decade or so on. However, in its painstaking attempts at detail in this rather artistic study of cruelty, the film is certainly an epic-length two hours, forty minutes in duration. This is more and more the trend in cinema these days, but I strongly feel that The Tiger could have curtailed one or two hunt scenes, for example, and retained or even improved much of its impact.

Sometimes a film self-consciously goes for the ‘epic’ tag, and it’s clear from the very outset that this is the case with Park Hoon-jung’s 2015 movie The Tiger. With its sweeping Korean vistas, Sturm und Drang musical score and lone figure set against an unforgiving world it clearly fits the bill, and actually that’s just fine: it’s a genre which seems to suit actor Choi Min-sik, perhaps best known for his work in the groundbreaking Oldboy (2005) which was in many ways an ordeal horror epic, when you think of it now, a decade or so on. However, in its painstaking attempts at detail in this rather artistic study of cruelty, the film is certainly an epic-length two hours, forty minutes in duration. This is more and more the trend in cinema these days, but I strongly feel that The Tiger could have curtailed one or two hunt scenes, for example, and retained or even improved much of its impact. This whole ‘man vs beast’ aspect of the film feels rather like The Revenant in places, a film which is its 2015 contemporary. Unlike the outraged mama bear in The Revenant, though, the ‘Mountain Lord’ here is more than an animal in many respects; the film plays fast and loose with animal realism in its (well-utilised) CGI sequences, and although the film is unsettlingly gruesome in its hunt scenes, there is a certain level of disparity of threat here too, as on occasion, the tiger becomes semi-mythic, something akin to a moral arbiter of the characters, killing savagely sometimes, but interacting rather differently sometimes. This shifting identity is something of a sticking point in the first half of the film; it’s not clear, for much of this time, what the tiger actually is. Still, eventually, a parity is created between the hunter and the tiger, which makes ever greater sense as the narrative progresses.

This whole ‘man vs beast’ aspect of the film feels rather like The Revenant in places, a film which is its 2015 contemporary. Unlike the outraged mama bear in The Revenant, though, the ‘Mountain Lord’ here is more than an animal in many respects; the film plays fast and loose with animal realism in its (well-utilised) CGI sequences, and although the film is unsettlingly gruesome in its hunt scenes, there is a certain level of disparity of threat here too, as on occasion, the tiger becomes semi-mythic, something akin to a moral arbiter of the characters, killing savagely sometimes, but interacting rather differently sometimes. This shifting identity is something of a sticking point in the first half of the film; it’s not clear, for much of this time, what the tiger actually is. Still, eventually, a parity is created between the hunter and the tiger, which makes ever greater sense as the narrative progresses.

I may as well be blunt here: it’s a notable book for many reasons, not least of which in how it’s generated so many more creative works down through the years, but I don’t think Dracula is a great novel in itself. The epistolary frame is interesting in terms of structure, and it’s cleverly pieced together, but this keeps readers at a distance from its protagonists; certain characters descend readily into farce (and are played faithfully as such in the film!) and there are a number of thankless questions, making the novel feel a bit like a whistle-stop tour of a fascinating place where you never have long to pause and look about you. Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula adds some sense and coherence to all of this by motivating its monster with undying love, but it doesn’t then abandon the effective and horrifying scenes from the book, either. Some of these – the creature turning into multiple rats which all flee, the still aged Dracula licking Harker’s blood from a cutthroat razor or impossibly scuttling down the castle’s steep walls – have lost none of their power. It’s these contrasts that allows the audience to see a fully-fleshed antagonist; to feel some ‘sympathy for the devil’, or at least sympathy for a damned being. Against the luxuriant add-on of what’s effectively a reincarnation based love story, it’s an absorbing array of contrasts.

I may as well be blunt here: it’s a notable book for many reasons, not least of which in how it’s generated so many more creative works down through the years, but I don’t think Dracula is a great novel in itself. The epistolary frame is interesting in terms of structure, and it’s cleverly pieced together, but this keeps readers at a distance from its protagonists; certain characters descend readily into farce (and are played faithfully as such in the film!) and there are a number of thankless questions, making the novel feel a bit like a whistle-stop tour of a fascinating place where you never have long to pause and look about you. Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula adds some sense and coherence to all of this by motivating its monster with undying love, but it doesn’t then abandon the effective and horrifying scenes from the book, either. Some of these – the creature turning into multiple rats which all flee, the still aged Dracula licking Harker’s blood from a cutthroat razor or impossibly scuttling down the castle’s steep walls – have lost none of their power. It’s these contrasts that allows the audience to see a fully-fleshed antagonist; to feel some ‘sympathy for the devil’, or at least sympathy for a damned being. Against the luxuriant add-on of what’s effectively a reincarnation based love story, it’s an absorbing array of contrasts. No one can ever accuse Coppola of shying away from things which could only ever be alluded to in 19th Century fiction. The Carmillas and Draculas of the day afforded the tantalising scope to be salacious, but likewise the sexual mores of the day meant calling things to a halt not too long after introducing this possibility of sex, couching even these supernatural encounters in veiled words and glaring omissions. Compare that, to give just one example, to the ‘Dracula’s Brides’ sequence in the 1992 release. Okay, even if the blood-sharing scene between Mina and the Count holds back to an extent (though still sending a million hearts a-flutter, no doubt) then the unholy trinity who make Harker their foodstuff/plaything must have been quite an education for more than a few young men – or women, for that matter. After that, we should be a hell of a lot more understanding as to why Harker’s speech sounds a little off. Then there’s what happens to Lucy Westenra, which is recounted as a ‘mystery illness’ in the novel, but is rendered overtly sexual on screen, in a series of eroticised, if dubiously consensual encounters – in one of which Oldman was advised to whisper scandalous nothings off-screen to actress Sadie Frost in order to encourage her to writhe appealingly. Coppola always intended his film to have this kind of sensory overload, storyboarding about a thousand scenes altogether and insisting that the costumes, alongside the mise-en-scène, underpinned the whole.

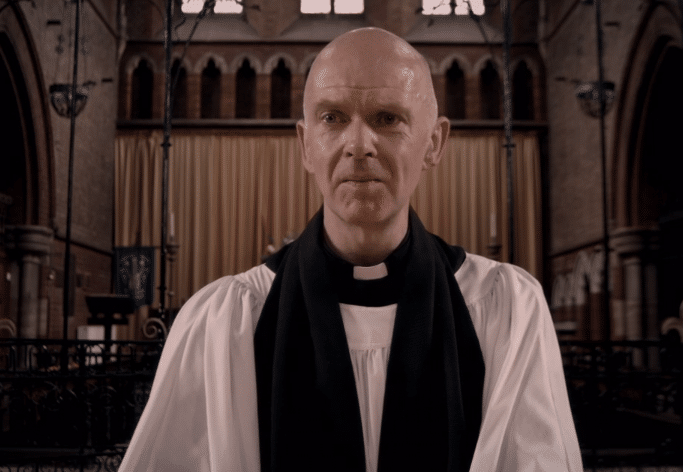

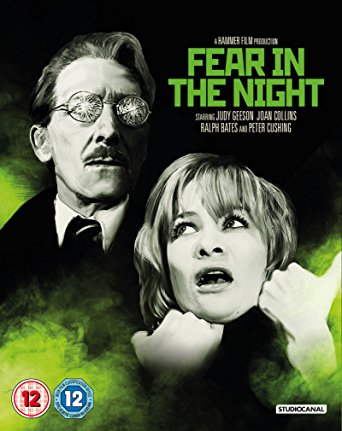

No one can ever accuse Coppola of shying away from things which could only ever be alluded to in 19th Century fiction. The Carmillas and Draculas of the day afforded the tantalising scope to be salacious, but likewise the sexual mores of the day meant calling things to a halt not too long after introducing this possibility of sex, couching even these supernatural encounters in veiled words and glaring omissions. Compare that, to give just one example, to the ‘Dracula’s Brides’ sequence in the 1992 release. Okay, even if the blood-sharing scene between Mina and the Count holds back to an extent (though still sending a million hearts a-flutter, no doubt) then the unholy trinity who make Harker their foodstuff/plaything must have been quite an education for more than a few young men – or women, for that matter. After that, we should be a hell of a lot more understanding as to why Harker’s speech sounds a little off. Then there’s what happens to Lucy Westenra, which is recounted as a ‘mystery illness’ in the novel, but is rendered overtly sexual on screen, in a series of eroticised, if dubiously consensual encounters – in one of which Oldman was advised to whisper scandalous nothings off-screen to actress Sadie Frost in order to encourage her to writhe appealingly. Coppola always intended his film to have this kind of sensory overload, storyboarding about a thousand scenes altogether and insisting that the costumes, alongside the mise-en-scène, underpinned the whole. Hammer is best-known for its Kensington Gore and its literary monsters, usually shot against a 60s-coloured 19th Century which is a distinctive aesthetic all of its own; the studio deviated from this formula quite considerably at times, though, in a range of films which seem to have divided critics ever since. Fear in the Night is certainly dramatically different from other projects which had seen director Jimmy Sangster at the helm: the last time he’d worked with Hammer prior to this film, it was to bring us Lust for a Vampire, a film which is itself divisive, but inarguably, classic Hammer fare. Not so with Fear in the Night, with its contemporary setting and extremely slow-burn approach. The film is not without its issues, but it certainly showcases the flexibility of Sangster. There’s ne’er a scrap of flimsy white fabric to be seen.

Hammer is best-known for its Kensington Gore and its literary monsters, usually shot against a 60s-coloured 19th Century which is a distinctive aesthetic all of its own; the studio deviated from this formula quite considerably at times, though, in a range of films which seem to have divided critics ever since. Fear in the Night is certainly dramatically different from other projects which had seen director Jimmy Sangster at the helm: the last time he’d worked with Hammer prior to this film, it was to bring us Lust for a Vampire, a film which is itself divisive, but inarguably, classic Hammer fare. Not so with Fear in the Night, with its contemporary setting and extremely slow-burn approach. The film is not without its issues, but it certainly showcases the flexibility of Sangster. There’s ne’er a scrap of flimsy white fabric to be seen. This is a very low-key piece of film, which takes its time establishing the interaction between Peggy’s state of mind and the possible threat to her. Unfortunately, some aspects of Peggy’s character and narrative haven’t aged particularly well; she behaves like a bit of a dupe, going from childlike to catatonic when the going gets tough. Mr. Carmichael’s wife Molly (Joan Collins) refers to her disparagingly as a ‘child bride’, and that is rather how she’s played. Eventually, she seems to withdraw from the plot altogether, every bit as unresponsive as Barbara in Night of the Living Dead. Before we get to that, though, Peggy is apparently primed to simply be ‘a teacher’s wife’, and having no other role, she has ample time to roam the grounds, where she has equally ample time to frighten herself half to death. The script accordingly does lag in several places, perhaps particularly where married life is concerned; perhaps as she is recovering from a mental illness (though we never discover the full nature of this) husband Bob is galvanised in his treatment of her as a lesser being, and the needy/dismissive dichotomy between them can be taxing.

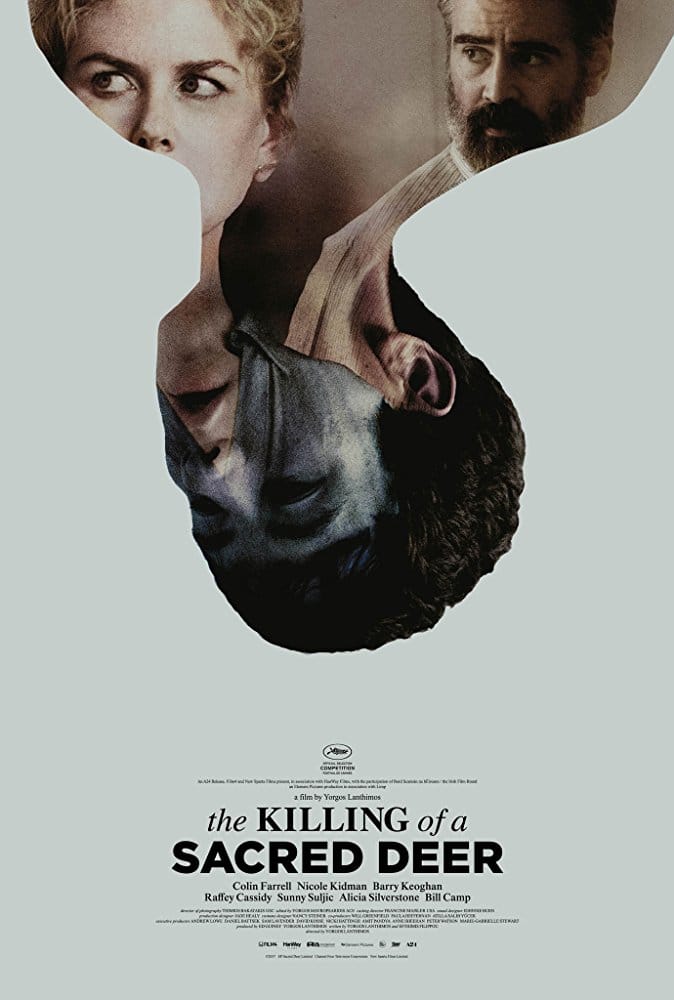

This is a very low-key piece of film, which takes its time establishing the interaction between Peggy’s state of mind and the possible threat to her. Unfortunately, some aspects of Peggy’s character and narrative haven’t aged particularly well; she behaves like a bit of a dupe, going from childlike to catatonic when the going gets tough. Mr. Carmichael’s wife Molly (Joan Collins) refers to her disparagingly as a ‘child bride’, and that is rather how she’s played. Eventually, she seems to withdraw from the plot altogether, every bit as unresponsive as Barbara in Night of the Living Dead. Before we get to that, though, Peggy is apparently primed to simply be ‘a teacher’s wife’, and having no other role, she has ample time to roam the grounds, where she has equally ample time to frighten herself half to death. The script accordingly does lag in several places, perhaps particularly where married life is concerned; perhaps as she is recovering from a mental illness (though we never discover the full nature of this) husband Bob is galvanised in his treatment of her as a lesser being, and the needy/dismissive dichotomy between them can be taxing. I will confess that I have had no prior experience of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s work, but based on his most recent film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, I’d imagine that a little goes a long way. That isn’t to say that I wasn’t completely drawn in to this twisted story of unhappy families, but that it’s left an unseemly, faintly uncomfortable after-effect; I found myself squirming in (rewarded) anticipation of horrible violence, and soon after, laughing at things I definitely didn’t feel I should be. It has all conspired to create a queasy sensation, one which clearly took work to establish, and isn’t going away in a hurry.

I will confess that I have had no prior experience of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s work, but based on his most recent film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, I’d imagine that a little goes a long way. That isn’t to say that I wasn’t completely drawn in to this twisted story of unhappy families, but that it’s left an unseemly, faintly uncomfortable after-effect; I found myself squirming in (rewarded) anticipation of horrible violence, and soon after, laughing at things I definitely didn’t feel I should be. It has all conspired to create a queasy sensation, one which clearly took work to establish, and isn’t going away in a hurry. Although loosely based on the Greek myth of Iphigenia – hence the title – The Killing of a Sacred Deer is right up to date, and full of very modern anxieties. Medicalisation, medical procedure, professional practice, wealth inequality and bereavement; here, these things are weaponised. As presented here, accompanied by an overwhelming, atonal soundtrack, the film is a fever dream anyway, but it sticks with the theme of sacrifice, pulling the already loosely-linked Murphy family apart via its genuinely effective, creepy central performance by Keoghan. The physicality of this young actor is – with apologies to the guy – well-suited to the role. He has a sly, usually emotionless face and a voice which betrays no emotion either, no matter what he says. He comes across as deeply unpleasant, and this eventually squeezes some terror and rage out of the Murphys – Steven becomes utterly unreasonable, whilst Anna turns into a conniving nightmare.

Although loosely based on the Greek myth of Iphigenia – hence the title – The Killing of a Sacred Deer is right up to date, and full of very modern anxieties. Medicalisation, medical procedure, professional practice, wealth inequality and bereavement; here, these things are weaponised. As presented here, accompanied by an overwhelming, atonal soundtrack, the film is a fever dream anyway, but it sticks with the theme of sacrifice, pulling the already loosely-linked Murphy family apart via its genuinely effective, creepy central performance by Keoghan. The physicality of this young actor is – with apologies to the guy – well-suited to the role. He has a sly, usually emotionless face and a voice which betrays no emotion either, no matter what he says. He comes across as deeply unpleasant, and this eventually squeezes some terror and rage out of the Murphys – Steven becomes utterly unreasonable, whilst Anna turns into a conniving nightmare. Meiko Kaji is, from a Western perspective, one of the most unmistakable and recognisable Japanese actresses of all time, but this comes with a significant proviso. Most of us know just a tiny fraction of the films she has ever made; only a handful of these nearly one hundred films have really made it over here anyway, and even out of that, we tend to think of her in one of a couple of key roles. Either Meiko Kaji is ‘Scorpion’, the largely mute and indestructible prison inmate of the Female Prisoner series, or she is the sword-wielding agent of doom in Lady Snowblood. This is a state of affairs acknowledged by author Tom Mes in his neat Meiko Kaji book Unchained Melody, available now on the Arrow Books imprint (and thus an extension of the work which Arrow has so far done in publicising Kaji’s work via their existing range of Meiko Kaji releases.)

Meiko Kaji is, from a Western perspective, one of the most unmistakable and recognisable Japanese actresses of all time, but this comes with a significant proviso. Most of us know just a tiny fraction of the films she has ever made; only a handful of these nearly one hundred films have really made it over here anyway, and even out of that, we tend to think of her in one of a couple of key roles. Either Meiko Kaji is ‘Scorpion’, the largely mute and indestructible prison inmate of the Female Prisoner series, or she is the sword-wielding agent of doom in Lady Snowblood. This is a state of affairs acknowledged by author Tom Mes in his neat Meiko Kaji book Unchained Melody, available now on the Arrow Books imprint (and thus an extension of the work which Arrow has so far done in publicising Kaji’s work via their existing range of Meiko Kaji releases.) I have a real love/hate thing going with Japanese director Sion Sono. On one hand, his so-called ‘hate’ trilogy contains, for me, some of the most genius, subversive films I have ever been immersed in; they’re absolutely jaw-dropping, to the point that I don’t know if I can feasibly revisit Guilty of Romance for fear of washing away that initial impact. He’s also made brilliant cinema with a far more playful edge, albeit for the fact that there’s usually a grim, self-referential message tucked away beneath the many layers of flying limbs and arterial gore. But on the other hand, when I sat down to watch his manga adaptation – usually an indication that things are about to go straight over my head – by the name of Tokyo Tribe, I have to confess I could stand to watch so little of it that I had to abort watching it at all. And I can usually make it through anything. It kind of goes with the territory. Yet here I was, switching off a film by someone I claimed was one of my favourite directors. A straightforward antipathy to hip-hop isn’t quite enough to explain that one.

I have a real love/hate thing going with Japanese director Sion Sono. On one hand, his so-called ‘hate’ trilogy contains, for me, some of the most genius, subversive films I have ever been immersed in; they’re absolutely jaw-dropping, to the point that I don’t know if I can feasibly revisit Guilty of Romance for fear of washing away that initial impact. He’s also made brilliant cinema with a far more playful edge, albeit for the fact that there’s usually a grim, self-referential message tucked away beneath the many layers of flying limbs and arterial gore. But on the other hand, when I sat down to watch his manga adaptation – usually an indication that things are about to go straight over my head – by the name of Tokyo Tribe, I have to confess I could stand to watch so little of it that I had to abort watching it at all. And I can usually make it through anything. It kind of goes with the territory. Yet here I was, switching off a film by someone I claimed was one of my favourite directors. A straightforward antipathy to hip-hop isn’t quite enough to explain that one. But whilst the justification for all the things which befall our protagonists feels rather hasty and unconvincing in the end, and perhaps a very short hop from the ultimate cop-out of saying it was all a dream, I think what we have here is, overall, a decent Sion Sono film which joins up with many of the styles and preoccupations he has explored previously and feels, at least, a lot truer to form. Really, he’s getting up to his usual mischief here. He’s splicing ultraviolence and cartoonish splatter with questions about, oh you know, selfhood, free will, memory, fate, all the small stuff, even if not dipping into his passion for literature along the way this time. What’s more, Sion Sono is doing all of this with his usual fantastic imagery, set pieces and symbolism – that innovative bridal bouquet is a clear winner – and, to come back to gender for a moment, he’s executing a meticulous disruption of the old archetype of the ‘y

But whilst the justification for all the things which befall our protagonists feels rather hasty and unconvincing in the end, and perhaps a very short hop from the ultimate cop-out of saying it was all a dream, I think what we have here is, overall, a decent Sion Sono film which joins up with many of the styles and preoccupations he has explored previously and feels, at least, a lot truer to form. Really, he’s getting up to his usual mischief here. He’s splicing ultraviolence and cartoonish splatter with questions about, oh you know, selfhood, free will, memory, fate, all the small stuff, even if not dipping into his passion for literature along the way this time. What’s more, Sion Sono is doing all of this with his usual fantastic imagery, set pieces and symbolism – that innovative bridal bouquet is a clear winner – and, to come back to gender for a moment, he’s executing a meticulous disruption of the old archetype of the ‘y