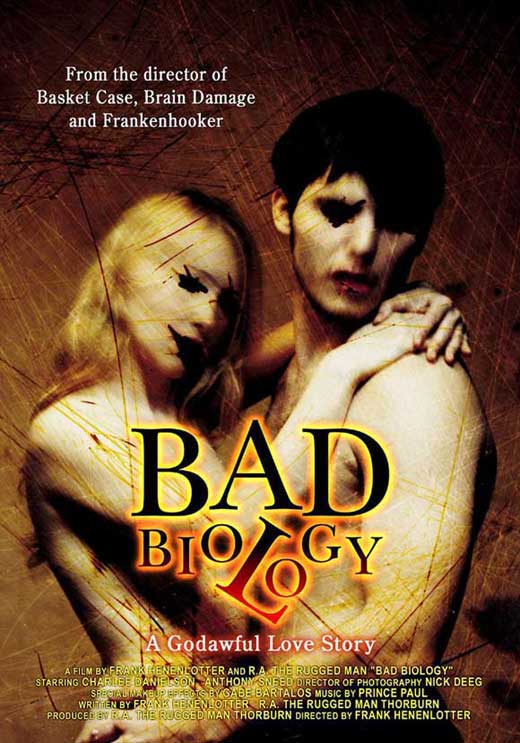

By anyone’s standards, sixteen years is a hell of a hiatus for a filmmaker to take between films. Yeah, from time to time this happens (Herschell Gordon Lewis went a staggering thirty years between The Gore Gore Girls and his next film) but overall, it’s still unusual. After all, if you’d taken that long a break, would fans still be into your work? Would your stuff still seem current? And would you be able to appeal to new audiences altogether? Well, it seems to me that if Frank Henenlotter gave any consideration to the above questions, he ended up deciding to throw them out altogether, and to make a film so outlandish and, let’s face it, alienating that only the truly dedicated, or else the truly unhinged would still be with him by the end. Hence Bad Biology (2008) starts as it means to go on, opening with the line, “I was born with seven clits…”

By anyone’s standards, sixteen years is a hell of a hiatus for a filmmaker to take between films. Yeah, from time to time this happens (Herschell Gordon Lewis went a staggering thirty years between The Gore Gore Girls and his next film) but overall, it’s still unusual. After all, if you’d taken that long a break, would fans still be into your work? Would your stuff still seem current? And would you be able to appeal to new audiences altogether? Well, it seems to me that if Frank Henenlotter gave any consideration to the above questions, he ended up deciding to throw them out altogether, and to make a film so outlandish and, let’s face it, alienating that only the truly dedicated, or else the truly unhinged would still be with him by the end. Hence Bad Biology (2008) starts as it means to go on, opening with the line, “I was born with seven clits…”

Far more sexually explicit than anything else he’s made, Bad Biology follows the fate of a young woman, a photographer called Jennifer (Charlee Danielson, who perhaps understandably isn’t listed as making anything else since on IMDb). Jennifer self-describes as ‘the girl with the crazy pussy’: her oddball body and urges set her at odds with all the normies around her, as much as she still needs them to scratch that itch. Little wonder meaningful relationships aren’t forthcoming though – being with her isn’t exactly a straightforward experience. Every time she has sex, she delivers a part-formed ‘freak baby’ within a couple of hours. Meanwhile, across town, we see a guy who is using a hell of a lot of chemicals to alter his own sexual performance. And not to ‘enhance’ it in a usual sense, either: he’s using farm grade medicines and industrial kit to get himself going. Perhaps inevitably, Jennifer and this troubled young man, Batz, are about to find one another…

No one could deny that Bad Biology is a brash calling-card to leave after sixteen years of peace and quiet. All I’d say is that if the exaggerated dialogue and sequences turn you off, such as a group of teenagers talking at some, err, length about feted American porn star John Holmes (would they know who he was?) then blame yourselves to a degree: the film’s opening line sets the bar, right before lowering it. That said, anyone expecting Henenlotter horror elements would probably be disappointed here, as I honestly was. Barring the mutant offspring theme, which gets only a minimal treatment, and a certain sequence towards the end of the film when Batz’s penis decides to go it alone, this is a film far, far more in the sexploitation vein. I suppose the film’s key nod to the horror material which preceded it is simply in how grotesque its sex scenes actually are. This film certainly isn’t intended as titillation, and it renders every sex scene into something horrible accordingly.

So we have a film which either sets out to shock, or doesn’t care that it does; we have a film which focuses on sex and provides a few moments of body horror, rather than a body horror which touches upon sex. So far, this doesn’t seem to have a great deal in common with earlier Henenlotter films, but there are a few elements which act as a bridge between the earlier films and the new. Fulfilling the more modern aspect, the soundtrack is modern, and New York has become rather gentrified; there’s some CGI in here, which isn’t great to look at. We also have Jennifer breaking the fourth wall, giving us a voiceover in places and addressing the audience directly – which is definitely something new. In other aspects, a lot of the coloured filters look like they’re straight out of the 80s and make the film appear older than it is, and when all’s said and done, Gabe Bartalos’s SFX work is still instantly recognisable. Who else would spend such time and effort on designing a ravening twenty inch monstrosity? I’ll tell you who: the guy who’s done it before.

As for attitudes to women, hmm. I don’t think you’d go to a filmmaker like Henenlotter expecting his work to reflect our modern preoccupations with gender, but those inclined would probably raise an eyebrow here. Lots of men in the film try to police Jennifer’s behaviour, slinging insults at her, acting like they’re the ones in control: it’s only thanks to her unorthodox make-up that she’s able to turn it around. She even turns their ‘little deaths’ (or actual deaths) into photographic essays. Past emotional attachments have ended up going badly wrong for her, so she now steers clear of them; she also shies away from that old adage ‘women have sex to get love’. She definitely doesn’t, and avoids it like the plague. All of that said and done, she does turn into a hysterical, irrational mess on occasion, and other women in the film dodge between being inert sets of boobs, and prostitutes. Honestly, I think it’s only the film’s elective preposterousness that has saved it from a glut of Vice articles about how a disembodied penis breaking into women’s apartments to sleep with them is deeply problematic. But all of its problematic content is just a facet of the film’s overall puerile nature, in my opinion. If women are characterised rather thinly, then so’s everyone else we meet.

As for attitudes to women, hmm. I don’t think you’d go to a filmmaker like Henenlotter expecting his work to reflect our modern preoccupations with gender, but those inclined would probably raise an eyebrow here. Lots of men in the film try to police Jennifer’s behaviour, slinging insults at her, acting like they’re the ones in control: it’s only thanks to her unorthodox make-up that she’s able to turn it around. She even turns their ‘little deaths’ (or actual deaths) into photographic essays. Past emotional attachments have ended up going badly wrong for her, so she now steers clear of them; she also shies away from that old adage ‘women have sex to get love’. She definitely doesn’t, and avoids it like the plague. All of that said and done, she does turn into a hysterical, irrational mess on occasion, and other women in the film dodge between being inert sets of boobs, and prostitutes. Honestly, I think it’s only the film’s elective preposterousness that has saved it from a glut of Vice articles about how a disembodied penis breaking into women’s apartments to sleep with them is deeply problematic. But all of its problematic content is just a facet of the film’s overall puerile nature, in my opinion. If women are characterised rather thinly, then so’s everyone else we meet.

Fans had a very long wait for Bad Biology – a title which, come to think of it, neatly sums up the themes we see in Frank Henenlotter’s best-known feature films. And, whilst this film isn’t on a par with his very best, it’s still got moments of pure Henenlotter, which are enjoyable; it’s certainly as ‘exploitation’ as anything he’s ever made, it’s knowingly, achingly trashy and it’s at its best in the end sequences, roaming body parts and all. In fact, the film feels a little like a dumping ground for every batshit insane idea Henenlotter has had since Basket Case 3, so perhaps these could have been developed a bit more, or divided up differently, and due to this ‘throw everything at it’ approach, it doesn’t feel as fully formed as his earlier films. It’s little wonder, if you look at fan reviews, that people are divided on this one. But it’s great that Henenlotter decided to make another film which still has his hallmarks, and as naive as it perhaps sounds, as a director who’s still working today, it would be great if he ever did decide to return to the body horror/exploitation cinema we know and love after another ten year break…

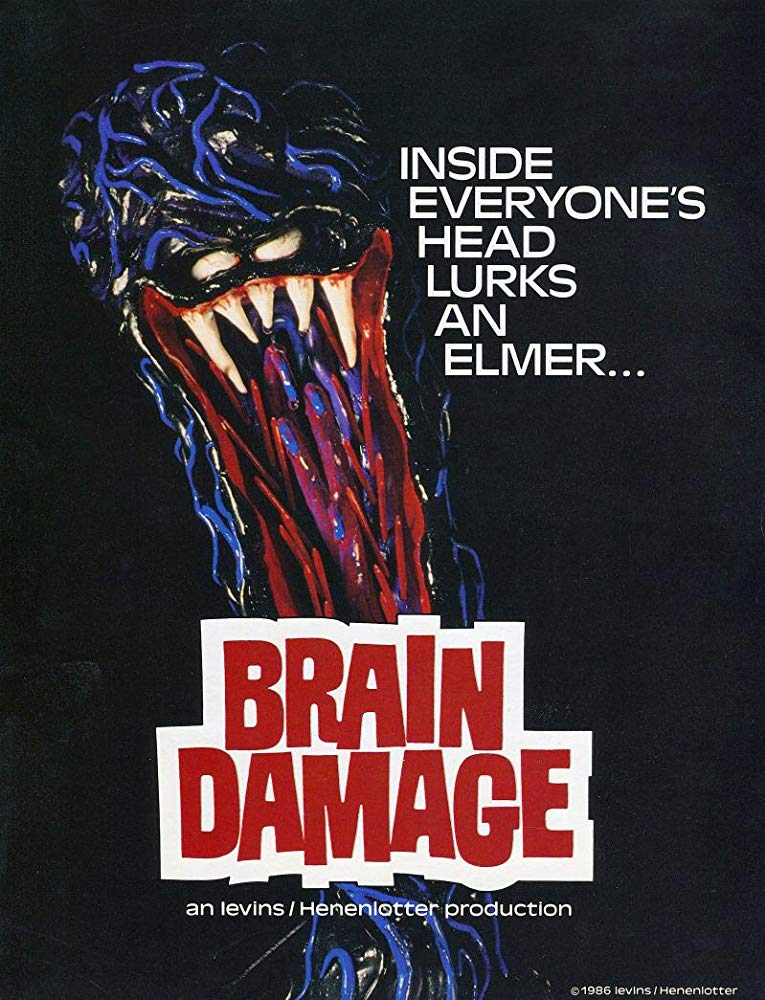

If you didn’t already know from your experience of watching Basket Case that bad things are almost certainly around the corner, then you could be forgiven for thinking that the beginning of Brain Damage (1988) features a perfectly respectable elderly couple, in a well-decorated New York apartment, doing something perfectly reasonable. Sure they’re feeding…something, but that’s probably a lhasa apso or something. Dogs eat anything, so they’d surely eat, umm, brains… from an ornate china plate…erm…in the tub…pets, eh?

If you didn’t already know from your experience of watching Basket Case that bad things are almost certainly around the corner, then you could be forgiven for thinking that the beginning of Brain Damage (1988) features a perfectly respectable elderly couple, in a well-decorated New York apartment, doing something perfectly reasonable. Sure they’re feeding…something, but that’s probably a lhasa apso or something. Dogs eat anything, so they’d surely eat, umm, brains… from an ornate china plate…erm…in the tub…pets, eh? It hardly needs saying that Brain Damage could work as a hideous metaphor for addiction. The highs, the lows, the people hurt, the desperate measures – they’re all in there. In fact the film seems to invite us to see Brian in this light on several occasions: as he prepares to head into the new wave gig where he meets the unfortunate fellatio brain-munch girl, for instance, there’s a back-and-forth shot of him getting his hit with an alcoholic down-and-out standing just a little way away, drinking from a brown paper bottle. Their ages are different and the substances are different, but these are both people with their dependencies.

It hardly needs saying that Brain Damage could work as a hideous metaphor for addiction. The highs, the lows, the people hurt, the desperate measures – they’re all in there. In fact the film seems to invite us to see Brian in this light on several occasions: as he prepares to head into the new wave gig where he meets the unfortunate fellatio brain-munch girl, for instance, there’s a back-and-forth shot of him getting his hit with an alcoholic down-and-out standing just a little way away, drinking from a brown paper bottle. Their ages are different and the substances are different, but these are both people with their dependencies. As much as I love all of Henenlotter’s films, Brain Damage is really my favourite. On a low budget, and with inexperienced actors (this was Rick Hearst’s first film) it achieves a great deal, striking a good balance between authentic horror and horror-comedy. It has a lot of the gritty, grimy nastiness of Basket Case, with the same mean streets and locations, content so graphic that it was excised from early cuts of the film, and horrible subject matter: in some respects it’s like Basket Case in reverse, with an unwitting joining-together of two sentient creatures, one ‘normal’ and one not, instead of an enforced coming-apart. So this whole symbiosis theme is pretty grim, and gives us some unpleasant scenes throughout.

As much as I love all of Henenlotter’s films, Brain Damage is really my favourite. On a low budget, and with inexperienced actors (this was Rick Hearst’s first film) it achieves a great deal, striking a good balance between authentic horror and horror-comedy. It has a lot of the gritty, grimy nastiness of Basket Case, with the same mean streets and locations, content so graphic that it was excised from early cuts of the film, and horrible subject matter: in some respects it’s like Basket Case in reverse, with an unwitting joining-together of two sentient creatures, one ‘normal’ and one not, instead of an enforced coming-apart. So this whole symbiosis theme is pretty grim, and gives us some unpleasant scenes throughout. A few years ago, at the Dead by Dawn horror festival in Edinburgh, I was invited to take part in a ‘play dead’ competition with the rest of the auditorium. Quite unusual as a pastime, you might think, even for a horror fest.

A few years ago, at the Dead by Dawn horror festival in Edinburgh, I was invited to take part in a ‘play dead’ competition with the rest of the auditorium. Quite unusual as a pastime, you might think, even for a horror fest. Henenlotter has not made a vast array of features during his career, though via his work with Something Weird he’s shown he’s as happy to save other people’s films from oblivion as he is to make his own. Altogether, he’s made eight original films, together with some documentary work, and at the time of writing his name is attached to a couple more shorts. Some directors crank out a film a year, but Henenlotter has never joined their ranks; there’s even been a sixteen-year hiatus between features. None of that means the impact of his work has been any less, and in a few very notable films in the 80s and 90s in particular, he’s made his name as a director of ‘body horror’, where the physical body can be invaded, mutated, updated and quite open blown apart by a whole host of bizarre phenomena. Some body horror is genuinely unsettling: close contemporary David Cronenberg, for instance, renders his compromised bodies the stuff of nightmares. It’s horrific, yes, but sublime. Henenlotter has a different approach – he opts to go straight from the sublime to the ridiculous. Sure, you can wince at some of the things he does on screen, but any deeper considerations are usually grabbed out of your hands by the next scene coming, which does something so hideously outlandish that all you can do is laugh. It is, as he suggests, pure exploitation, and it’s terrific entertainment, as well as immensely formative for many of us of a certain age, who grew up with these films on VHS and later, DVD.

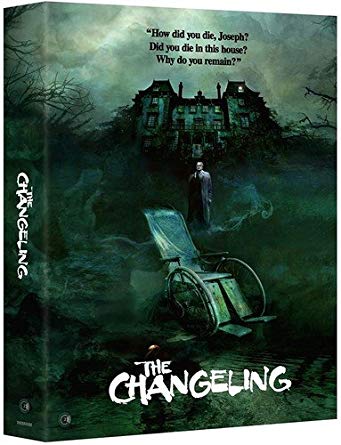

Henenlotter has not made a vast array of features during his career, though via his work with Something Weird he’s shown he’s as happy to save other people’s films from oblivion as he is to make his own. Altogether, he’s made eight original films, together with some documentary work, and at the time of writing his name is attached to a couple more shorts. Some directors crank out a film a year, but Henenlotter has never joined their ranks; there’s even been a sixteen-year hiatus between features. None of that means the impact of his work has been any less, and in a few very notable films in the 80s and 90s in particular, he’s made his name as a director of ‘body horror’, where the physical body can be invaded, mutated, updated and quite open blown apart by a whole host of bizarre phenomena. Some body horror is genuinely unsettling: close contemporary David Cronenberg, for instance, renders his compromised bodies the stuff of nightmares. It’s horrific, yes, but sublime. Henenlotter has a different approach – he opts to go straight from the sublime to the ridiculous. Sure, you can wince at some of the things he does on screen, but any deeper considerations are usually grabbed out of your hands by the next scene coming, which does something so hideously outlandish that all you can do is laugh. It is, as he suggests, pure exploitation, and it’s terrific entertainment, as well as immensely formative for many of us of a certain age, who grew up with these films on VHS and later, DVD. Winter, upstate New York. The Russell family are on vacation, but their vehicle has broken down in the snow. As father John (George C. Scott) crosses the road to call for help, an out-of-control truck careers towards his wife and daughter. A simple and effective cut to John, alone and back in the city, tells the audience all it needs to know; it’s the first understated moment of the film which shows that director Peter Medak trusts us to understand what’s going on without spelling everything out for us. The family home is now boxed up, with only flashbacks to show us what it once was.

Winter, upstate New York. The Russell family are on vacation, but their vehicle has broken down in the snow. As father John (George C. Scott) crosses the road to call for help, an out-of-control truck careers towards his wife and daughter. A simple and effective cut to John, alone and back in the city, tells the audience all it needs to know; it’s the first understated moment of the film which shows that director Peter Medak trusts us to understand what’s going on without spelling everything out for us. The family home is now boxed up, with only flashbacks to show us what it once was. Everything is handled with a sensitive pace, allowing characterisation to blossom without having Russell say everything he’s thinking; slowly and surely, he picks his way through a story which effectively leads him/us down a few blind alleys, arriving at its surprising denouement cautiously. I’d also argue that in the best supernatural horrors, the haunted place – usually a house – seems to operate as a character in its own right. Before we can safely attribute phenomena to a specific entity, we can only interpret the strangeness of the haunted place itself. It is the source of the phenomena, so it needs to seem almost sentient, as well as striking in aesthetics and atmosphere. The house in The Changeling has all of this in abundance, too. Camera angles are shot from the house’s perspective, and it’s described by Russell himself as having wants and preferences. Again, it’s simple stuff I suppose, but done well it’s very effective. The film does more, too, by linking its supernatural to real-life events, which calls up far older ideas that ‘justice will out’ to a very modern tale of corruption.

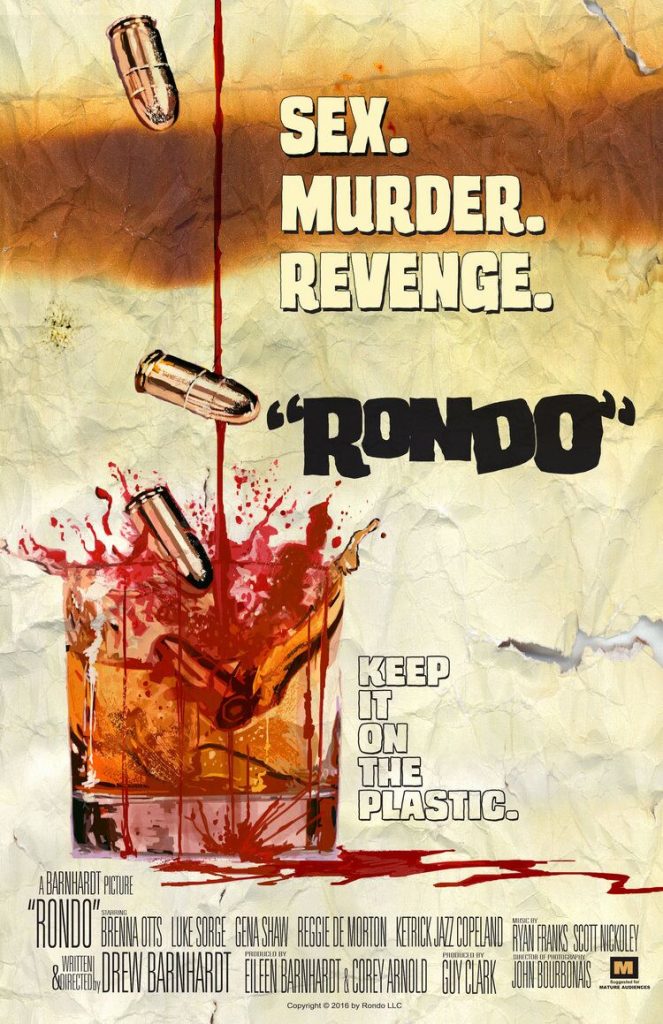

Everything is handled with a sensitive pace, allowing characterisation to blossom without having Russell say everything he’s thinking; slowly and surely, he picks his way through a story which effectively leads him/us down a few blind alleys, arriving at its surprising denouement cautiously. I’d also argue that in the best supernatural horrors, the haunted place – usually a house – seems to operate as a character in its own right. Before we can safely attribute phenomena to a specific entity, we can only interpret the strangeness of the haunted place itself. It is the source of the phenomena, so it needs to seem almost sentient, as well as striking in aesthetics and atmosphere. The house in The Changeling has all of this in abundance, too. Camera angles are shot from the house’s perspective, and it’s described by Russell himself as having wants and preferences. Again, it’s simple stuff I suppose, but done well it’s very effective. The film does more, too, by linking its supernatural to real-life events, which calls up far older ideas that ‘justice will out’ to a very modern tale of corruption. How much can one ninety-minute film reasonably do within its timeframe? Can a film successfully go from awkward laughs to gore, from femmes fatales to OTT-ultraviolence, and from slacker humour to shock? Rondo (2018) believes it’s not only possible, it’s all part and parcel of its overall appeal. Both the ethos and the resulting movie have a few little drawbacks, but overall, I’d say those behind the film manage to balance these things pretty well. Due to its content this will not be a film for everyone, but if you can laugh and squirm at the same time, you might well be okay with this one.

How much can one ninety-minute film reasonably do within its timeframe? Can a film successfully go from awkward laughs to gore, from femmes fatales to OTT-ultraviolence, and from slacker humour to shock? Rondo (2018) believes it’s not only possible, it’s all part and parcel of its overall appeal. Both the ethos and the resulting movie have a few little drawbacks, but overall, I’d say those behind the film manage to balance these things pretty well. Due to its content this will not be a film for everyone, but if you can laugh and squirm at the same time, you might well be okay with this one. If they weren’t already on your radar, it’s at about this point that the film’s black comedy elements begin to rise. As Paul and some of the other gatherers listen to the ‘rules of the road’ for this party, the script modulates between comedic and downright sleazy; if the film showed half the things it describes, it’d have an X rating, which makes the steady delivery of certain lines by the host, Lurdell (Reggie De Morton) seem all the more uneasily funny. Paul’s suspicions about this place and this set-up are ultimately – and quickly – confirmed, so he decides to disappear. But he can’t just do that, or put this strange night behind him. It’s not as simple as that.

If they weren’t already on your radar, it’s at about this point that the film’s black comedy elements begin to rise. As Paul and some of the other gatherers listen to the ‘rules of the road’ for this party, the script modulates between comedic and downright sleazy; if the film showed half the things it describes, it’d have an X rating, which makes the steady delivery of certain lines by the host, Lurdell (Reggie De Morton) seem all the more uneasily funny. Paul’s suspicions about this place and this set-up are ultimately – and quickly – confirmed, so he decides to disappear. But he can’t just do that, or put this strange night behind him. It’s not as simple as that. Umberto Lenzi turned his hand to many different kinds of genre film during his career, so it’s perhaps little surprise that he looked to the kind of cannibalism movies being made by his peers (such Ruggero Deodato), making two of them in very rapid succession, after almost a ten-year break between these and the first of his films to nod towards anthropophagy, The Man from the Deep River. Cannibal Ferox and Eaten Alive were made within a year of each other, though I’d suggest that Ferox is still the better-known title of the two, often for some of its more notorious scenes, and perhaps still for its association with the ‘video nasty’ debacle, which has so often led to a long legacy of different cuts and titles.

Umberto Lenzi turned his hand to many different kinds of genre film during his career, so it’s perhaps little surprise that he looked to the kind of cannibalism movies being made by his peers (such Ruggero Deodato), making two of them in very rapid succession, after almost a ten-year break between these and the first of his films to nod towards anthropophagy, The Man from the Deep River. Cannibal Ferox and Eaten Alive were made within a year of each other, though I’d suggest that Ferox is still the better-known title of the two, often for some of its more notorious scenes, and perhaps still for its association with the ‘video nasty’ debacle, which has so often led to a long legacy of different cuts and titles. In many respects Ferox is a sort-of morality tale, whereby every white person setting foot in the Amazon basin is an irredeemable fool, nasty beyond measure, and so they get served accordingly. Even Gloria eventually fathoms this, bless. However, they don’t simply get picked off in order of awfulness, with some of the better-meaning characters dying way before the worst of them, so it’s not as straightforward as it might be. It’s also worth knowing with these cannibal horrors that a lot of the more notorious and gory scenes are often crammed into a short amount of time, usually towards the end of the ninety minutes: they certainly are here, and in common with

In many respects Ferox is a sort-of morality tale, whereby every white person setting foot in the Amazon basin is an irredeemable fool, nasty beyond measure, and so they get served accordingly. Even Gloria eventually fathoms this, bless. However, they don’t simply get picked off in order of awfulness, with some of the better-meaning characters dying way before the worst of them, so it’s not as straightforward as it might be. It’s also worth knowing with these cannibal horrors that a lot of the more notorious and gory scenes are often crammed into a short amount of time, usually towards the end of the ninety minutes: they certainly are here, and in common with  Given some of the films which have showcased Eastern European locations for American audiences in recent years, you’d be forgiven for thinking that in every disused industrial building in this part of the world, there’s some sort of dodgy sex-and-torment club holding sway. Such is the case in Dark Crimes (2016), which crams quite a lot of breasts and torture into its opening scenes; this scene actually takes place outside of the timeframe of the rest of the film and as such is a little confusing, but quite possibly it seemed a shame not to add it in. These considerations aside, Dark Crimes is probably most noteworthy for its casting of Jim Carrey in the lead role – though it’s languished a while, two years in fact, waiting for a release, which seems surprising given his bankability. Well, having now watched the film in its entirety, let’s just say I’m rather less surprised that it’s been left sitting on a shelf somewhere.

Given some of the films which have showcased Eastern European locations for American audiences in recent years, you’d be forgiven for thinking that in every disused industrial building in this part of the world, there’s some sort of dodgy sex-and-torment club holding sway. Such is the case in Dark Crimes (2016), which crams quite a lot of breasts and torture into its opening scenes; this scene actually takes place outside of the timeframe of the rest of the film and as such is a little confusing, but quite possibly it seemed a shame not to add it in. These considerations aside, Dark Crimes is probably most noteworthy for its casting of Jim Carrey in the lead role – though it’s languished a while, two years in fact, waiting for a release, which seems surprising given his bankability. Well, having now watched the film in its entirety, let’s just say I’m rather less surprised that it’s been left sitting on a shelf somewhere. As for Carrey, I suppose you could say this is a change of pace for him – but then again, he’s already proven he can do serious acting elsewhere. Once the initial mild surprise of seeing him looking so dour wears off, you realise he’s being given very little to do here; that dour stare is the whole role. He also veers between a neutral accent (better) and an attempt at an Eastern European one (worse), which just makes it doubly silly. (It’s never really explained why the whole of Poland is conducting its affairs exclusively in English, right down to the TV news. Only the names are Polish in this version of Poland.) Charlotte Gainsbourg has a role here, too, one which grows in importance as the film moves forward, but she essentially reprises the role she’s done several times elsewhere, with a completely unsurprising nude scene/sex scene and a strung-out demeanour overall. To be fair, she isn’t permitted any characterisation for most of the film, so it’s all too little, too late when it finally comes along.

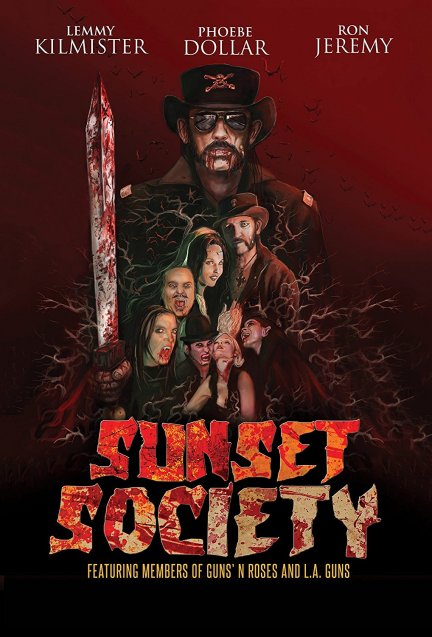

As for Carrey, I suppose you could say this is a change of pace for him – but then again, he’s already proven he can do serious acting elsewhere. Once the initial mild surprise of seeing him looking so dour wears off, you realise he’s being given very little to do here; that dour stare is the whole role. He also veers between a neutral accent (better) and an attempt at an Eastern European one (worse), which just makes it doubly silly. (It’s never really explained why the whole of Poland is conducting its affairs exclusively in English, right down to the TV news. Only the names are Polish in this version of Poland.) Charlotte Gainsbourg has a role here, too, one which grows in importance as the film moves forward, but she essentially reprises the role she’s done several times elsewhere, with a completely unsurprising nude scene/sex scene and a strung-out demeanour overall. To be fair, she isn’t permitted any characterisation for most of the film, so it’s all too little, too late when it finally comes along. I don’t know about you, but I always feel a moment of trepidation when I see rock stars’ names attached to film projects – perhaps particularly so when at least one of the rock stars in question has now shuffled off the mortal coil. What would they have thought of the finished product? Did it receive their blessing? What’s the story? That’s very much the case in Sunset Society, a film which boasts an appearance by the legendary, and now sadly deceased Lemmy Kilmister, as well as roles for LA Guns musician Tracii Guns and former Guns ‘n’ Roses member Dizzy Reed. The largest share of Sunset Society seems to be as a meet-up for LA-based musicians and hangers-on who peaked before the 21st century came around, although admittedly that doesn’t really apply to the Motorhead frontman. Director/actress Phoebe Dollar – veteran of a whole host of low-budget horrors in her own right – isn’t an idiot, and Lemmy is accordingly plastered all over the film’s promotional material, because he is quite simply a failsafe currency as far as rock and metal fans are concerned. He’s also mentioned frequently in the script by other characters, though it’s worth pointing out that this is, really speaking, a cameo role, with only a few minutes of screen time for him.

I don’t know about you, but I always feel a moment of trepidation when I see rock stars’ names attached to film projects – perhaps particularly so when at least one of the rock stars in question has now shuffled off the mortal coil. What would they have thought of the finished product? Did it receive their blessing? What’s the story? That’s very much the case in Sunset Society, a film which boasts an appearance by the legendary, and now sadly deceased Lemmy Kilmister, as well as roles for LA Guns musician Tracii Guns and former Guns ‘n’ Roses member Dizzy Reed. The largest share of Sunset Society seems to be as a meet-up for LA-based musicians and hangers-on who peaked before the 21st century came around, although admittedly that doesn’t really apply to the Motorhead frontman. Director/actress Phoebe Dollar – veteran of a whole host of low-budget horrors in her own right – isn’t an idiot, and Lemmy is accordingly plastered all over the film’s promotional material, because he is quite simply a failsafe currency as far as rock and metal fans are concerned. He’s also mentioned frequently in the script by other characters, though it’s worth pointing out that this is, really speaking, a cameo role, with only a few minutes of screen time for him. I really, really wish there was more to it than that. Lots of the screen time here seems to consist of only loosely-connected scenes, with little in the sense of a driving force behind the narrative. Sure, some of the aesthetics are pretty cool, some of the city nightscapes look effective and if you like seeing pretty goth girls on screen then you’ll find plenty to divert you, but it all feels more like a protracted music video than a coherent film. Adding to this, lots of the dialogue feels improvised (and some of it has blatantly been messed up, but left in anyway) or there are issues with the script whereby it frequently becomes thin or repetitive. Making a joke out of the repetitiveness itself is not enough to swing it, unfortunately, even if it’s stalwart Ron Jeremy making the attempt: his is another cameo role, with little screen time given. (Oh, and another, more inexplicable cameo? Steve-o from Jackass.) As for Lemmy himself, well as much as it’s good to see him again, his scenes aren’t all that great. He was never an actor by trade and towards the end of his life, he seems he’s struggling to enunciate the lines given to him. The cheap animated interludes hardly help matters.

I really, really wish there was more to it than that. Lots of the screen time here seems to consist of only loosely-connected scenes, with little in the sense of a driving force behind the narrative. Sure, some of the aesthetics are pretty cool, some of the city nightscapes look effective and if you like seeing pretty goth girls on screen then you’ll find plenty to divert you, but it all feels more like a protracted music video than a coherent film. Adding to this, lots of the dialogue feels improvised (and some of it has blatantly been messed up, but left in anyway) or there are issues with the script whereby it frequently becomes thin or repetitive. Making a joke out of the repetitiveness itself is not enough to swing it, unfortunately, even if it’s stalwart Ron Jeremy making the attempt: his is another cameo role, with little screen time given. (Oh, and another, more inexplicable cameo? Steve-o from Jackass.) As for Lemmy himself, well as much as it’s good to see him again, his scenes aren’t all that great. He was never an actor by trade and towards the end of his life, he seems he’s struggling to enunciate the lines given to him. The cheap animated interludes hardly help matters. As we’ve seen countless times, the weight of expectation can be an ambiguous gift to a film, but it’s fair to say that few recent horrors have enjoyed such a steadily-building sense of anticipation as Hereditary (2018), which has been running tantalising trailers for the past few months. For one thing, the return of Toni Collette to the horror genre has been a boon – she really is a superb actress for this kind of thing – and for another, we seem to be enjoying a run of supernatural horror; it’s a welcome development for fans, some of whom may have felt somewhat starved of it in recent years. That said, the now-obligatory discussions about whether or not Hereditary is a horror film at all have proved to be a rather tedious add-on, unnecessary and bewildering for fans of the genre, who already know that it can do all of the sophisticated, multi-layered things which seem to come as such a surprise to others that they need to feel around for a new title for it every single time. I tried, as ever, to put all of this to the back of my mind ahead of seeing the film – which lo and behold, is as much of a horror film as I’ve ever seen in my life.

As we’ve seen countless times, the weight of expectation can be an ambiguous gift to a film, but it’s fair to say that few recent horrors have enjoyed such a steadily-building sense of anticipation as Hereditary (2018), which has been running tantalising trailers for the past few months. For one thing, the return of Toni Collette to the horror genre has been a boon – she really is a superb actress for this kind of thing – and for another, we seem to be enjoying a run of supernatural horror; it’s a welcome development for fans, some of whom may have felt somewhat starved of it in recent years. That said, the now-obligatory discussions about whether or not Hereditary is a horror film at all have proved to be a rather tedious add-on, unnecessary and bewildering for fans of the genre, who already know that it can do all of the sophisticated, multi-layered things which seem to come as such a surprise to others that they need to feel around for a new title for it every single time. I tried, as ever, to put all of this to the back of my mind ahead of seeing the film – which lo and behold, is as much of a horror film as I’ve ever seen in my life. I’m deliberately keeping my plot synopsis brief and a little vague here, as the way in which Hereditary unfolds deserves to be appreciated with as open a mind as possible. It’s unlikely that I’m spoilering by relating to the supernatural elements, though, I hope; so, this is a supernatural horror through and through, where the afterlife is more of a parallel world than a one-way destination, and where its inmates can harbour very, very sinister designs on the living. I was pleasantly surprised to find myself surprised, I think. I’ve seen the film proudly described as ‘this generation’s Exorcist’, or words to that effect, but that seems an odd comparison to make, unless we’re painting in very broad strokes. It’s far closer to the malignity of The Witch, or indeed the assault-by-wicked-forces seen in Drag Me To Hell, though with less of the humour. Although, even Hereditary has its lighter moments. It lobs in a few bong jokes, and some of the family meltdowns grow so hysterical that they verge on black comedy, as do a few of the film’s shockingly graphic moments.

I’m deliberately keeping my plot synopsis brief and a little vague here, as the way in which Hereditary unfolds deserves to be appreciated with as open a mind as possible. It’s unlikely that I’m spoilering by relating to the supernatural elements, though, I hope; so, this is a supernatural horror through and through, where the afterlife is more of a parallel world than a one-way destination, and where its inmates can harbour very, very sinister designs on the living. I was pleasantly surprised to find myself surprised, I think. I’ve seen the film proudly described as ‘this generation’s Exorcist’, or words to that effect, but that seems an odd comparison to make, unless we’re painting in very broad strokes. It’s far closer to the malignity of The Witch, or indeed the assault-by-wicked-forces seen in Drag Me To Hell, though with less of the humour. Although, even Hereditary has its lighter moments. It lobs in a few bong jokes, and some of the family meltdowns grow so hysterical that they verge on black comedy, as do a few of the film’s shockingly graphic moments. The cannibal movie cycle of the late Seventies and early Eighties will forever seem like a strange beast. Splicing stock footage of animals doing their thing with often garish animal cruelty, then layering in gore effects, nudity and any number of practices which would very likely fail to get past an ethics committee today, the resultant films are nonetheless compelling – in their own way. All of that said, I’m a product of my own social climate, and as such I’m very pleased that Shameless Films have openly made the decision to ‘soften’ (their term) the animal cruelty originally present in their brand new version of Mountain of the Cannibal God (1978), making the point that this footage benefits the film’s narrative none. Instead, they’ve worked to restore other missing scenes, offering the usual proviso that this means some of the splicing is bound to be noticeable. And it is, a little, but it’s all in the pursuit of a worthwhile cut of this film, and the end results are very good.

The cannibal movie cycle of the late Seventies and early Eighties will forever seem like a strange beast. Splicing stock footage of animals doing their thing with often garish animal cruelty, then layering in gore effects, nudity and any number of practices which would very likely fail to get past an ethics committee today, the resultant films are nonetheless compelling – in their own way. All of that said, I’m a product of my own social climate, and as such I’m very pleased that Shameless Films have openly made the decision to ‘soften’ (their term) the animal cruelty originally present in their brand new version of Mountain of the Cannibal God (1978), making the point that this footage benefits the film’s narrative none. Instead, they’ve worked to restore other missing scenes, offering the usual proviso that this means some of the splicing is bound to be noticeable. And it is, a little, but it’s all in the pursuit of a worthwhile cut of this film, and the end results are very good. A haze of ulterior motives, animal scenes and great music ensue. It’s my contention that the best-known cannibal movies have such superb music for this very reason, to offset everything less palatable in a kind of cinematic karma. And as the team approach the mountain, the locals (of course) show this disapproval in all of the ways you might imagine, as well as a few which are, to be fair, very creative and ambitious. On a restricted budget, Martino achieves impressive things here; a lot of the entertainment value of these films comes from smirking at the flaws, and that’s fine, but don’t let that make you overlook the many things which Martino does rather well. The ‘mountain god’ himself looks genuinely gruesome and repellent, and some of those restored gore scenes could still make you flinch.

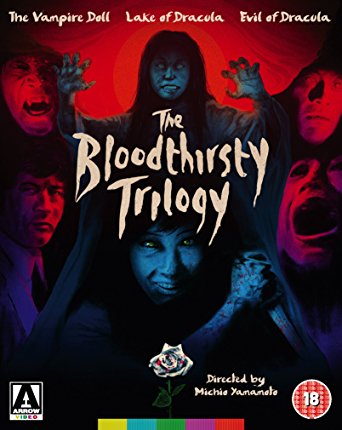

A haze of ulterior motives, animal scenes and great music ensue. It’s my contention that the best-known cannibal movies have such superb music for this very reason, to offset everything less palatable in a kind of cinematic karma. And as the team approach the mountain, the locals (of course) show this disapproval in all of the ways you might imagine, as well as a few which are, to be fair, very creative and ambitious. On a restricted budget, Martino achieves impressive things here; a lot of the entertainment value of these films comes from smirking at the flaws, and that’s fine, but don’t let that make you overlook the many things which Martino does rather well. The ‘mountain god’ himself looks genuinely gruesome and repellent, and some of those restored gore scenes could still make you flinch. Inspired by the success of Hammer’s lurid horror cinema in the 1960s, the ever-versatile Toho Studios made a sound business decision to make some vampire films of their own. Whilst there is a modest array of films based specifically on Far Eastern vampire lore, the productions overseen by director Michio Yamamoto are rather different, blending Western tropes with a decidedly more Japanese spin on the folklore. The resulting projects, on offer here as part of one package released by Arrow Films, are an aesthetically-pleasing blend of whimsy and clever ideas, and would certainly be of interest to anyone with a fancy for seeing how world cinema does it.

Inspired by the success of Hammer’s lurid horror cinema in the 1960s, the ever-versatile Toho Studios made a sound business decision to make some vampire films of their own. Whilst there is a modest array of films based specifically on Far Eastern vampire lore, the productions overseen by director Michio Yamamoto are rather different, blending Western tropes with a decidedly more Japanese spin on the folklore. The resulting projects, on offer here as part of one package released by Arrow Films, are an aesthetically-pleasing blend of whimsy and clever ideas, and would certainly be of interest to anyone with a fancy for seeing how world cinema does it. In terms of the cultural melding of East and West, there are some aspects of this to ponder, as well as interesting rationales for the emergence of vampires which are interesting, looking quite different to those in European films (but with similarities too: vampire women love a nice white gown). I rather like the golden eyes which the vampire characters have, too, even if you can’t help but wonder if they ran with that idea once they’d thought of it. However, I don’t think there are massively poignant cultural messages here, not really; there is an explanation in Evil of Dracula for how said count’s influence made its way to Japan, but the Japanese always seem rather relaxed about this kind of detail, and whilst you could ponder the presence of Western houses etc. as having more to say, equally you could just enjoy the spectacle on offer. If there’s one thing I found particularly interesting, it’s the use of hypnotism in the films’ plots; the development of this theme has a lot more in common with Poe than Mesmer himself, and it makes for some interesting denouements.

In terms of the cultural melding of East and West, there are some aspects of this to ponder, as well as interesting rationales for the emergence of vampires which are interesting, looking quite different to those in European films (but with similarities too: vampire women love a nice white gown). I rather like the golden eyes which the vampire characters have, too, even if you can’t help but wonder if they ran with that idea once they’d thought of it. However, I don’t think there are massively poignant cultural messages here, not really; there is an explanation in Evil of Dracula for how said count’s influence made its way to Japan, but the Japanese always seem rather relaxed about this kind of detail, and whilst you could ponder the presence of Western houses etc. as having more to say, equally you could just enjoy the spectacle on offer. If there’s one thing I found particularly interesting, it’s the use of hypnotism in the films’ plots; the development of this theme has a lot more in common with Poe than Mesmer himself, and it makes for some interesting denouements.