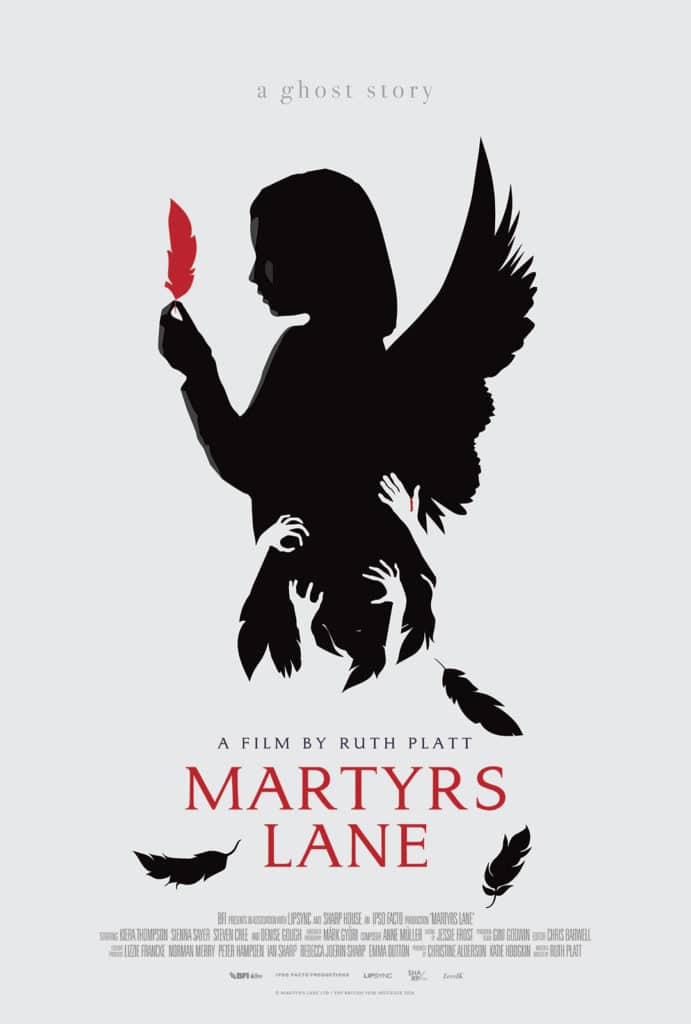

Any expectations I had for Martyrs Lane (2021) were very quickly blown out of the water; it’s a ghostly tale which in many ways feels like it comes from an earlier time, having more in common with the subtle horrors of the 60s and 70s than the flashier, quick edits of modern cinema. This is a heartbreaking and very intimate domestic drama, centred plausibly and sensitively on the experiences of children, perhaps between Paperhouse (1988) and The Others (2001) in terms of its content and tone. But it is very much its own story, too.

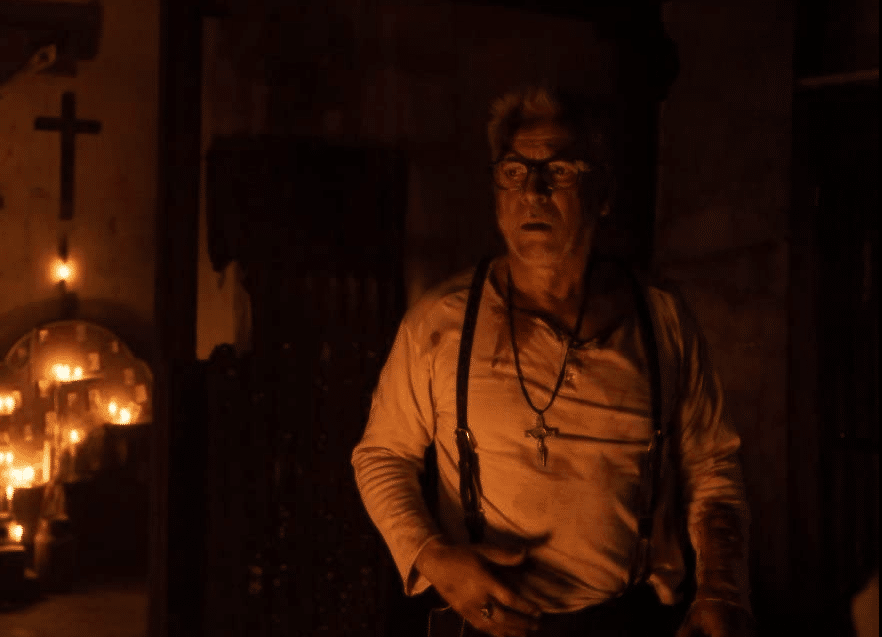

Leah (the superb Kiera Thompson) is an isolated little girl who seems to be troubled by a fear of the dark and ominous dreams at night. By day, she seems to exist as something between invisible and a nuisance to the adults in her life. She’s about to be Confirmed at the local church, where her father is the minister, but there are early hints that her religious feelings are quite genuine and not just part and parcel of her father’s role, family pressure, or anything like that. She believes in angels, or what she perceives to be angels, and seems fascinated by stories about them.

One day, this bright but conflicted little girl sees another child in the woods near her house – not long after big sister Bex has been trying to scare her with stories of Tudor ghosts who walk again at night. This isn’t scary, though; the little girl seems to be about her own age, and, innocently, Leah tells her she can come to her house, if she wants to. That evening, she does, tapping on Leah’s bedroom window and asking for her help.

A different filmmaker might have continued the Wuthering Heights similarity here in grisly fashion, just like the novel, but Martyrs Lane director Ruth Platt isn’t about that. No blood washes down the window panes here. The new friendship between the two children – and what ensues – makes for a deeply sophisticated story, blending familiar aspects of ghost lore with cultural beliefs about the special abilities which children have to see things which, as adults, we say aren’t there. Think of all those stories we share about ‘invisible friends’, and what they could be. But it isn’t just a ghost story. It’s underpinned by other plot devices, and these work together to make Leah’s story a rich, intricate and often unbearably tense one. For example, the family dynamic here is incredibly strained, particularly between Leah, mother Sarah (Denise Gough) and Bex (Hannah Rae). There’s an unpleasant, simmering tension which manifests itself in a variety of ways, said and unsaid. At first, the conversation between the two little girls is very open and natural by comparison; it makes a pleasant change to some of the other exchanges which take place, even if it doesn’t remain that way.

The film really excels in its representation of that gap between adults and children; it’s a representation which, in places, makes for difficult viewing. It’s not comfortable to watch. Firstly, this is because it can be difficult to recall the specific nature and intensity of childhood fears: we’re largely socialised out of them. Martyrs Lane brings them back, doing so from the perspective of a little girl you can’t help but empathise with, whether she is anxiously using a torch to look for whatever might be making a noise in the dark, or (most poignantly of all) struggling to gain any recognition from the people in her life who should love her. Again, the film handles this brilliantly. The camera frequently stays at Leah’s height, or at least it does early on in the film, which helps to demonstrate the physical distance between her and the adults. It also often peers down at her, making her seem all the more vulnerable. The sound design is really important too, as it keeps adult conversations distant, a miserable babble which breaks off here and there only to scold Leah, or at best to trot out all the usual things people say to kids to get them to behave. It feels genuinely like relief when an adult is kind to her.

Leah, does, thankfully, get a little more interaction as the film moves on, though that tension and distance is always there on the periphery, in much the same way as Leah is – always on the threshold, looking in. So Martyrs Lane successfully captures both a child’s susceptibility to strange phenomena but also aspects of their powerlessness, but it also knows it’s being watched by adults: some of the moments of peril make you cringe as any adult would, watching a child steadily putting themselves at more and more risk.

As the film progresses, you may be able to make an educated guess at the backbone of the plot, but that does not take anything away from how the story unfolds. Elements of mystery, particularly the use of objects and clues, are used carefully as scares and revelations are doled out just as carefully, but they’re no less unsettling for that; some developments here are deeply unpleasant and unsettling. Ultimately, Martyrs Lane takes an oblique, almost delicate approach to grief, family and childhood in a thoughtful, confident way. It never misses a beat, and it sticks with you perhaps a little uncomfortably after viewing.

The World Premiere of Martyrs Lane will take place at the 25th Fantasia Film Festival.