It’s interesting how accounts of the later years of Hammer Films can vary according to the tastes of the writer. Some will sigh in resignation at how the once great company lost its way as the times changed; others, such as myself whose early horror education largely consisted of films from that era, look back on it as a wonderful period, even if it did mark the end of Hammer as we knew it (I think it’s fair to say the recently resurrected brand is pretty far removed from what once was). Others might not even know or care much about Hammer at all: I heartily recommend these people track down The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula (or, depending on where you live, Horror of Dracula) post-haste and work your up way from there, because you don’t know what you’re missing.

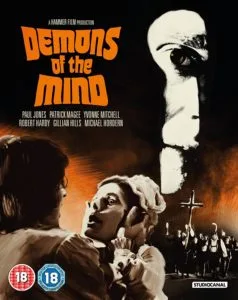

We open on Elizabeth (Gillian Hills), a beautiful young blonde-haired woman in a diaphanous white nightgown, sitting in a horse-drawn carriage. So far, so Hammer. However, as a matronly older woman (Yvonne Mitchell) pulls her hand away from the window and tells her everything’s going to be alright once she’s back home, things immediately feel a bit off. The young lady seems catatonic. A wordless flashback montage ensues; we see her wandering in the woods, being taken aback by a young male stranger who she later takes as her lover (70s Hammer, after all); but then she’s back at her home, naturally a brooding Gothic mansion, with a father (Robert Hardy) who seems just a little too pleased to have her home, and a brother (Shane Briant) who seems even less emotionally stable than she is, and also displays concern for his sibling which seems more than fraternal. It transpires that the father, Baron Zorn, fears for the minds of his children, believing a curse is upon them following the suicide of his wife many years earlier. To this end, he brings a supposed specialist in the mind, Falkenberg (Patrick Magee), into his home to help cure their ailments via his somewhat experimental techniques. However, it may be too little too late, as a series of murders have occurred in the village, some of the victims being young women close to Elizabeth in appearance; and the villagers, not without reason, suspect the mad Baron and his children are to blame.

I was fascinated to learn from the newly-produced featurette on the Blu-ray that producer/story writer Frank Godwin originally pitched Demons of the Mind to Hammer as a werewolf movie, yet it was at the insistence of Hammer themselves that the monster element was removed. This I find fairly astonishing, as one would think a werewolf movie would be a considerably easier sell; and, indeed, it’s little surprise to learn that Demons of the Mind died a death at the box office, not least because distributor EMI didn’t have a clue what to do with it. Even in their grislier, skin-heavy early 70s days, there’s always been a certain homeliness to Hammer, at least in part because you tend to know what you’re getting when the lights go down; but in this instance, it’s really hard to predict where things are going from scene to scene. For some this may make for a more rewarding experience, but those with a particular fondness for the standard Hammer formula might be put off. Another interesting side note: the mansion setting was used that same year in Sergio Martino’s All the Colours of the Dark, which leads me to ponder whether, beyond Hammer’s standard Germanic period setting, Demons of the Mind might be closer to a Giallo in terms of narrative and theme. (Or maybe I’m stretching there. Anyway, John Hough later shot The Legend of Hell House there too, so however you cut it, it’s a great backdrop for people going nuts.)

Any way you cut it, Demons of the Mind clearly does a better job presenting a more modern brand of horror than the same year’s Dracula AD 1972 – and I say that as someone with an unshakeable affection for that camp and corny schlocker. If, like me, you’re a Hammer fan who’s missed this one up to now, take this opportunity to make amends. It’s not your standard Hammer, but in this instance that really isn’t a bad thing at all.

Demons of the Mind is released in dual format DVD and Blu-ray on 30th October, from Studiocanal.