Editor’s note: this discussion of Men Behind the Sun contains spoilers.

Editor’s note: this discussion of Men Behind the Sun contains spoilers.

The Chinese film Men Behind the Sun (1988) is not altogether well known in the West, and has yet to enjoy the kind of lavish DVD or indeed Blu-Ray release which has usually happened for even the most censor-baiting movies by thirty years after their creation. Those who have not seen the film itself, but know a little about it, will probably know about its notorious reputation for gore, perhaps for several key scenes in particular; before I ever got hold of a copy, I knew about ‘the autopsy scene’ and ‘the frostbite scene’ from hushed discussions in magazines and fanzines, for example, and I’m willing to bet many readers here will have heard similar things. These scenes are still, undeniably, important and shocking in the extreme (and more so, when you learn a little about how they were done) but I think it’s a real disservice to the work of director Tun Fei Mou if his film is known only for these. These scenes, and others like them, should never exist in isolation in our imaginations – as merely grisly little tableaux to be relished by gorehounds. Men Behind the Sun is a phenomenal film, in which even the most seemingly outlandish scenes have their basis in historical fact, and however appalling the scenes are to watch, they’re of vital importance to the narrative of the film as a whole. In essence, the entire film is a scream of agony by the Chinese about their WWII treatment at the hands of the Japanese; its rage is measured and doled out in a well-constructed, engrossing story. I will acknowledge that it’s difficult to watch. But I feel that anyone with even a passing interest in the history of the Far East should see it, and should be upset by it. These things should upset us, and should be acknowledged.

As the film explains in its opening scenes, aggressive Japanese empire-building in the early decades of the twentieth century had seen it conquer wide swathes of the Far East, including Korea and parts of China. Expansionist ideals were by no means and have never been the exclusive tenure of the West, and so the Japanese occupied parts of countries which they considered to be populated by people decidedly less cultured than themselves. Throughout the decade, closer and closer relations with Nazi Germany – though often problematic – saw the Japanese essentially following a similar path of conflict, taking territory whilst prevaricating in its attitudes and alliances with the global powers by now in play. They also committed themselves to a small-scale, but no less brutal nor important programme of medical experimentation, targeted towards boosting their war efforts, but as with the experiments eventually undertaken by the Nazis in Europe, also overlaid with the pure cruelty of curiosity, when that curiosity finds subjects deemed less than human.

The district of Manchuria (North-East China) was under complete Japanese control after 1931. It was in this region that the Japanese established Unit 731, their flagship biological and chemical warfare research facility. At the end of the war, the Japanese did a remarkable and meticulous job of covering their tracks, destroying many records of what had taken place, but enough has survived to reveal a sadistic programme of experiments performed upon mainly the Han Chinese, though also on Soviets, Allies, Mongolians and Koreans. Men Behind the Sun is a film about Unit 731, and the young (almost child) Japanese soldiers forced to help oversee operations. In order to equip them to do their new jobs, the camp’s military and medical hierarchy has to essentially break down their humanity. The boys can no longer see the local Chinese as simply people, but as ‘marut’ – literally ‘logs’, but a word which I believe translates best as ‘guinea pigs’, simply fodder for experimentation. They try to be obedient, as any good Japanese soldier would; they prevaricate, however, when the cruelty of their masters impinges upon their lives in the most brutal way, when a local child who has been their friend is taken, killed and his organs harvested. He’s taken so quietly, because the boys themselves are told to bring him, and he trusts them. Their sense of betrayal is authentically upsetting to watch and phenomenally acted by the young cast.

To make this scene (one amongst many) even more skin-crawling, rumours that this scene contains a real autopsy turns out to be quite true. When a local child died in an accident, Tun Fei Mou somehow prevailed upon the doctors performing the child’s post-mortem to allow him to use footage: the deceased was about the same height and weight as the child actor for the scene, so it has that unsettling note of veritas. The doctors (incredibly) accommodated his request, even dressing in Japanese uniform to complete the procedure. The organs we see being removed are, so we’re told, pig organs rather than human, though it seems an odd concession to modesty when we’ve just seen a real child’s corpse being cut into. Likewise, the notorious ‘rats can overpower a cat’ scene where a cat is apparently mauled to death by rats is now being denied as real by the director, though it looks very, very much like an animal genuinely dies here. This sort of thing could of course never, ever happen today, and it’s bizarre that it ever did, but even if we can’t quite accept it, we can perhaps explain it by the fact that at this time, there was no SFX industry in China, and Tun Fei Mou felt it was of the utmost importance to show the experiments as they really were. He couldn’t have found anyone to make rubber models for key scenes, and even if he could, perhaps this would have gravely affected the film he was trying to make.

To make this scene (one amongst many) even more skin-crawling, rumours that this scene contains a real autopsy turns out to be quite true. When a local child died in an accident, Tun Fei Mou somehow prevailed upon the doctors performing the child’s post-mortem to allow him to use footage: the deceased was about the same height and weight as the child actor for the scene, so it has that unsettling note of veritas. The doctors (incredibly) accommodated his request, even dressing in Japanese uniform to complete the procedure. The organs we see being removed are, so we’re told, pig organs rather than human, though it seems an odd concession to modesty when we’ve just seen a real child’s corpse being cut into. Likewise, the notorious ‘rats can overpower a cat’ scene where a cat is apparently mauled to death by rats is now being denied as real by the director, though it looks very, very much like an animal genuinely dies here. This sort of thing could of course never, ever happen today, and it’s bizarre that it ever did, but even if we can’t quite accept it, we can perhaps explain it by the fact that at this time, there was no SFX industry in China, and Tun Fei Mou felt it was of the utmost importance to show the experiments as they really were. He couldn’t have found anyone to make rubber models for key scenes, and even if he could, perhaps this would have gravely affected the film he was trying to make.

Real body parts are used for all of the film’s most horrific scenes. This includes the infamous scene I alluded to above, where a marut Chinese woman (fresh from having her surplus-to-requirements newborn smothered to death in the snow) is given slow, prolonged frostbite by having her arms extended through a hole in an outside wall into the freezing winter conditions. When her arms are completely dead, she first has her arms thawed in warm water, and then Dr. demonstrates how you can then skin the flesh from the bones; it flays off easily. The actress playing this part – Mou’s niece – held a real corpse’s arms out into the subzero temperatures in order to freeze them, nearly getting frostbite herself, and then holds onto them for the main scene. The overall effect is utterly repellent and – as revealed in a 1995 New York Times article, whose author was made privy to Japanese testimony – it really happened to people. Limbs were really frozen and flayed. Limbs were bludgeoned, to see if any feeling remained. The overall feeling I get from this scene, apart from obviously flinching, is the director’s real sense of anger that this ever happened to Chinese people. We’re forced to look at this in as exact a replica of the events in question as it is feasible to give, and the impact is immense. Of course, viewers are welcome to look at it simply as a gory scene and thousands no doubt have, but I think it’s missing the point.

I won’t simply talk through every scene in this horrific history lesson, but I will say I feel none of them are chosen simply by chance, or to shock for their own sakes. The effect of the film is to steadily, unhesitatingly paint a picture of a unique point in history, with content always rooted firmly in that history, and underpinned by character studies which give the film its strongest juxtapositions. The sadistic personality of Shiro Ishii, for example, is a man devoted to Japan, whose big break in the progress of biological warfare comes from a laugh he has after a trip to a brothel. You can spread bubonic plague, he realises, by distributing infected fleas in porcelain bombs. And of course, this is also true. It’s worth bearing in mind that this man was given immunity by the Americans after the war, and continued to work, turning up at front-line institutions to wield his expertise. In fact, after offering us another gruelling juxtaposition (the Japanese woman who gives birth as the camp burns, giving us one last glimpse of life opposing death) it is revealed to us that Shiro’s Eureka moment led to a real outbreak of bubonic plague in Manchuria. Plague, which was at one time scheduled for use against California, had Japan not surrendered after America unleashed atomic bombs upon them…

“Friendship is friendship; history is history.”

When Men Behind the Sun was first made, it offered, interestingly, something of an issue for the modern China which had produced it: China was, by this point, keen to keep a good working and economic relationship with Japan, now a neighbour with whom it had long enjoyed peace. This neatly underlines how much the world had changed by this point, with young Chinese and Japanese people being gripped by so little of the negativity which would have been hugely significant to even their nearest ancestors. It is right and good that the sins of the fathers should not spill over into modern China or Japan; an ever-dwindling number of people even survive who could have been implicated in any of these events, and no one benefits when new generations are made to labour under whatever modern version of original sin we now think is befitting.

However, nor should we shy away from unpalatable truths. Where many historical films can be taken to task for tinkering with history, rendering it more tolerable or even misrepresenting recorded facts in order to offer a different version of events, Men Behind the Sun is rather different fare, and audiences were unsurprisingly shocked by it all, with Japanese audiences in particular finding it hard to bear. Several sequels followed, each in turn examining more unpalatable histories, though never quite as shockingly as Men Behind the Sun did. This film does everything it can to tell its story, taking every opportunity to show us what is strongly believes in, with no need to embellish, and a wholesale rejection of glossing over anything. This it does by shocking means, and by using methods which would today be illegal. This means that Men Behind the Sun has more of a reputation as an exploitation movie, an understandable but, to my mind misleading state of affairs which threatens to dismiss a unique film about a little-known period of time. It’s a period in time, it’s worth remembering, which was very nearly kept secret forever. Had the Japanese officials at Unit 731 been any more thorough in its cover-up, no one would ever have known what befell tens of thousands of people who ended up there.

I can end this feature with nothing further other than to reiterate my belief in the film’s essential worth, and to point again to the quote which runs over the film’s opening credits (quoted above) – words which sum up the weight of the past, without succumbing entirely to it. The world into which Men Behind the Sun was released was indeed benefiting from friendship with the old adversary, but nothing can ever take away what had happened, and a film of this calibre and nature ensures that we learn from the bloody lessons of history. It’s a fitting and a sobering legacy.

Some films excel at that kind of grimy, disconcerting quality which Possum (2018) has in abundance. Every frame of this film makes your skin crawl: it’s a love letter to abandoned places and anonymous spaces, swept through with dead foliage and rot. This, in and of itself, makes the film fairly challenging viewing, even whilst you can appreciate the skill which went into arranging its sets and locations throughout. Add to this an arachnid puppet which seems to stand in for a grown man’s arrested development and mental trauma, and you have a fairly gruelling viewing experience. However, Possum doesn’t lend itself particularly readily to a coherent narrative – with the result that those not hypnotised by its interesting looks might find the whole experience as frustrating as it is unsettling.

Some films excel at that kind of grimy, disconcerting quality which Possum (2018) has in abundance. Every frame of this film makes your skin crawl: it’s a love letter to abandoned places and anonymous spaces, swept through with dead foliage and rot. This, in and of itself, makes the film fairly challenging viewing, even whilst you can appreciate the skill which went into arranging its sets and locations throughout. Add to this an arachnid puppet which seems to stand in for a grown man’s arrested development and mental trauma, and you have a fairly gruelling viewing experience. However, Possum doesn’t lend itself particularly readily to a coherent narrative – with the result that those not hypnotised by its interesting looks might find the whole experience as frustrating as it is unsettling. As the film progresses, Philip looks authentically more and more haunted by Possum, and seemingly more and more in need of getting things off his chest. It is certainly impressive to see how Harries manages to enact this increasing sense of oppression, as he almost disappears inside himself during the film’s progress. He also looks authentically ill, which is testament at least to the turmoil he’s feeling, even if he describes it very little indeed. In some respects Possum reminds me of the underappreciated Tony (2009), another film with a troubled, but unseemly male main character. As for Philip, his desperation to burn or to ditch the horrible puppet thing is, we see, useless; the more he seems to try to deal with this nightmarish situation, the more Possum appears, spider-limbed and vicious, in his dreams. Some of the sequences in Possum are genuinely unsettling, capturing something of those helpless childhood fears which so many of us seek in the horror cinema we watch as adults. Director/writer Matthew Holness clearly appreciates a good, creeping scare, and can bring a certain sense of a child’s powerlessness to the screen.

As the film progresses, Philip looks authentically more and more haunted by Possum, and seemingly more and more in need of getting things off his chest. It is certainly impressive to see how Harries manages to enact this increasing sense of oppression, as he almost disappears inside himself during the film’s progress. He also looks authentically ill, which is testament at least to the turmoil he’s feeling, even if he describes it very little indeed. In some respects Possum reminds me of the underappreciated Tony (2009), another film with a troubled, but unseemly male main character. As for Philip, his desperation to burn or to ditch the horrible puppet thing is, we see, useless; the more he seems to try to deal with this nightmarish situation, the more Possum appears, spider-limbed and vicious, in his dreams. Some of the sequences in Possum are genuinely unsettling, capturing something of those helpless childhood fears which so many of us seek in the horror cinema we watch as adults. Director/writer Matthew Holness clearly appreciates a good, creeping scare, and can bring a certain sense of a child’s powerlessness to the screen. A noir-ish montage of images and a voiceover ruminating on the immorality of Hollywood introduces The Queen of Hollywood Blvd, a self-professed crime drama which promises to pitch a hard-bitten club owner against the tactics of a gang of organised criminals. On paper, the film does just this – but the style and tone involved are not what many would expect, and indeed anyone expecting a high-action piece of work would find themselves feeling all at sea after watching this movie. Your tolerance for this take on a crime story depends very much on your tolerance for slow-burn, almost art-house cinema generally.

A noir-ish montage of images and a voiceover ruminating on the immorality of Hollywood introduces The Queen of Hollywood Blvd, a self-professed crime drama which promises to pitch a hard-bitten club owner against the tactics of a gang of organised criminals. On paper, the film does just this – but the style and tone involved are not what many would expect, and indeed anyone expecting a high-action piece of work would find themselves feeling all at sea after watching this movie. Your tolerance for this take on a crime story depends very much on your tolerance for slow-burn, almost art-house cinema generally. I also found that some minor issues caught my eye; some continuity issues are in there, but then a bigger issue is that the film’s position in time was unclear. I found myself wondering why, say, one of the crooks had a framed picture of Reagan on the wall and VCRs figure in the plot, but then the streets are full of modern vehicles and the girls at the club have very modern-style tattoos. It could be that the film has opted quite deliberately to belong to that timeless, rootless type of setting which focuses fashionably on the lo-fi and doesn’t want us to know when these events are taking place, but I always find this distracting personally, an attempt to ignore time which makes me wonder about nothing else. (It Follows, I’m looking in your direction here.) But all of these things would be minor, were it not for the fact that The Queen of Hollywood Blvd is, I am afraid to say, quite so slow and ponderous as it is. Its deliberate pace and minimal action means that very little happens within the first hour; unless the atmosphere is note-perfect and engrossing, then this can be alienating. It even risks an audience’s engagement completely, something which worked against it in my case.

I also found that some minor issues caught my eye; some continuity issues are in there, but then a bigger issue is that the film’s position in time was unclear. I found myself wondering why, say, one of the crooks had a framed picture of Reagan on the wall and VCRs figure in the plot, but then the streets are full of modern vehicles and the girls at the club have very modern-style tattoos. It could be that the film has opted quite deliberately to belong to that timeless, rootless type of setting which focuses fashionably on the lo-fi and doesn’t want us to know when these events are taking place, but I always find this distracting personally, an attempt to ignore time which makes me wonder about nothing else. (It Follows, I’m looking in your direction here.) But all of these things would be minor, were it not for the fact that The Queen of Hollywood Blvd is, I am afraid to say, quite so slow and ponderous as it is. Its deliberate pace and minimal action means that very little happens within the first hour; unless the atmosphere is note-perfect and engrossing, then this can be alienating. It even risks an audience’s engagement completely, something which worked against it in my case. Editor’s note: this discussion of Men Behind the Sun contains spoilers.

Editor’s note: this discussion of Men Behind the Sun contains spoilers. To make this scene (one amongst many) even more skin-crawling, rumours that this scene contains a real autopsy turns out to be quite true. When a local child died in an accident, Tun Fei Mou somehow prevailed upon the doctors performing the child’s post-mortem to allow him to use footage: the deceased was about the same height and weight as the child actor for the scene, so it has that unsettling note of veritas. The doctors (incredibly) accommodated his request, even dressing in Japanese uniform to complete the procedure. The organs we see being removed are, so we’re told, pig organs rather than human, though it seems an odd concession to modesty when we’ve just seen a real child’s corpse being cut into. Likewise, the notorious ‘rats can overpower a cat’ scene where a cat is apparently mauled to death by rats is now being denied as real by the director, though it looks very, very much like an animal genuinely dies here. This sort of thing could of course never, ever happen today, and it’s bizarre that it ever did, but even if we can’t quite accept it, we can perhaps explain it by the fact that at this time, there was no SFX industry in China, and Tun Fei Mou felt it was of the utmost importance to show the experiments as they really were. He couldn’t have found anyone to make rubber models for key scenes, and even if he could, perhaps this would have gravely affected the film he was trying to make.

To make this scene (one amongst many) even more skin-crawling, rumours that this scene contains a real autopsy turns out to be quite true. When a local child died in an accident, Tun Fei Mou somehow prevailed upon the doctors performing the child’s post-mortem to allow him to use footage: the deceased was about the same height and weight as the child actor for the scene, so it has that unsettling note of veritas. The doctors (incredibly) accommodated his request, even dressing in Japanese uniform to complete the procedure. The organs we see being removed are, so we’re told, pig organs rather than human, though it seems an odd concession to modesty when we’ve just seen a real child’s corpse being cut into. Likewise, the notorious ‘rats can overpower a cat’ scene where a cat is apparently mauled to death by rats is now being denied as real by the director, though it looks very, very much like an animal genuinely dies here. This sort of thing could of course never, ever happen today, and it’s bizarre that it ever did, but even if we can’t quite accept it, we can perhaps explain it by the fact that at this time, there was no SFX industry in China, and Tun Fei Mou felt it was of the utmost importance to show the experiments as they really were. He couldn’t have found anyone to make rubber models for key scenes, and even if he could, perhaps this would have gravely affected the film he was trying to make. There have been many horror films about environmental havoc over the years, but it seems as though frogs have not figured prominently in these. Aside from the game-changing (or even life-changing) Hell Comes to Frogtown and a short cameo in Baskin, frogs have been largely overlooked, so I’ll admit: the press information for Strange Nature won me over via its apparent novelty, speaking of mutant frogs and the like. It’s possibly strange that we’ve seen so few amphibians in horror cinema; frogs have to live with us, have to cope with whatever we flush into the water, and their habitat has an immediate effect on them. This brings us to rural Minnesota, where the story begins.

There have been many horror films about environmental havoc over the years, but it seems as though frogs have not figured prominently in these. Aside from the game-changing (or even life-changing) Hell Comes to Frogtown and a short cameo in Baskin, frogs have been largely overlooked, so I’ll admit: the press information for Strange Nature won me over via its apparent novelty, speaking of mutant frogs and the like. It’s possibly strange that we’ve seen so few amphibians in horror cinema; frogs have to live with us, have to cope with whatever we flush into the water, and their habitat has an immediate effect on them. This brings us to rural Minnesota, where the story begins. The film at this juncture could have gone, to my mind, in one of two ways. Either it could have gone all out with glorious excess, using its environmental theme as an excuse to hurl froggy gore at the screen, or else elected to look quite seriously at the topic of pollution and its aftermath. Perhaps surprisingly, at least to my mind, the film largely opts for the latter. This is a very script-heavy film with a lot of dialogue employed to develop character and motivation, though thanks to this it feels a little slow in the middle act, and after Tiffany Shepis departs proceedings very early (she’s criminally underused here, and generally deserves more appreciation for sheer work ethic alone) it feels as though we’ve just been tantalised with the promise of some huge aggressive monster-creature. Instead, Kim is all about exorcising her demons as a former pop singer who made the mistake of insulting the denizens of Tuluth before heading off to a better life, and so she ends up working with the local elementary school science teacher to understand the situation and hopefully alert the locals to what’s happening before it’s Too Late.

The film at this juncture could have gone, to my mind, in one of two ways. Either it could have gone all out with glorious excess, using its environmental theme as an excuse to hurl froggy gore at the screen, or else elected to look quite seriously at the topic of pollution and its aftermath. Perhaps surprisingly, at least to my mind, the film largely opts for the latter. This is a very script-heavy film with a lot of dialogue employed to develop character and motivation, though thanks to this it feels a little slow in the middle act, and after Tiffany Shepis departs proceedings very early (she’s criminally underused here, and generally deserves more appreciation for sheer work ethic alone) it feels as though we’ve just been tantalised with the promise of some huge aggressive monster-creature. Instead, Kim is all about exorcising her demons as a former pop singer who made the mistake of insulting the denizens of Tuluth before heading off to a better life, and so she ends up working with the local elementary school science teacher to understand the situation and hopefully alert the locals to what’s happening before it’s Too Late. You have to hand it to director and writer Fred Dekker. Not only has he made some of the most straightforwardly entertaining films of the past forty years or so, but those films are – for many people – forever wedded to the 1980s, so forming part of people’s nostalgia for a decade when many of them were growing up and experiencing cinema for the first time. Even for those who didn’t see his films within the decade they were made (I never saw the film under discussion here until I was well into adulthood) the effect and the charm seems the same. Dekker might not have set out to set down the 80s for future audiences, but he captures something about them perfectly nonetheless, even when he was imagining a dystopian future, or a time in the past. Although his directorial work is sadly minimal, he has also worked on a number of seminal movies in the capacity of a writer, and he has a very distinguished style which

You have to hand it to director and writer Fred Dekker. Not only has he made some of the most straightforwardly entertaining films of the past forty years or so, but those films are – for many people – forever wedded to the 1980s, so forming part of people’s nostalgia for a decade when many of them were growing up and experiencing cinema for the first time. Even for those who didn’t see his films within the decade they were made (I never saw the film under discussion here until I was well into adulthood) the effect and the charm seems the same. Dekker might not have set out to set down the 80s for future audiences, but he captures something about them perfectly nonetheless, even when he was imagining a dystopian future, or a time in the past. Although his directorial work is sadly minimal, he has also worked on a number of seminal movies in the capacity of a writer, and he has a very distinguished style which  Night of the Creeps starts in the 1950s, when an alien skirmish taking place in the skies above Earth results in a mysterious capsule being jettisoned from the craft. It falls to Earth, where it soon threatens to interrupt the romantic pursuits of a group of white-bread young college students, two of whom see it land (and, being idiots, simply have to go and investigate). Oh, there’s a crazed axe murderer on the loose on the same evening; it never rains but it pours. After we see the worst happen with respect to both of these events, we cut to 1986. The weird, weird world of US college life is getting into full swing for that academic year, including the traditions of potential fraternity and sorority house inmates undertaking dangerous/stupid things as ‘pledges’ (seriously, America: why do you do it to yourselves?) Two outsiders, ‘dorks’ Chris (Jason Lively) and best friend J. C. (Steve Marshall) are doing their best to navigate through this new, potentially fraught social situation, as well as hankering after beautiful, probably inaccessible girls like Cynthia Cronenberg (Jill Whitlow). Sadly for them, it turns out that to get anywhere either socially or romantically, they’ll have to actually sign up for a pledge of their own – as set by a group of probable future Republican party candidates, who make it good and difficult. Their task? To break out a cryogenically frozen corpse from the local hospital.

Night of the Creeps starts in the 1950s, when an alien skirmish taking place in the skies above Earth results in a mysterious capsule being jettisoned from the craft. It falls to Earth, where it soon threatens to interrupt the romantic pursuits of a group of white-bread young college students, two of whom see it land (and, being idiots, simply have to go and investigate). Oh, there’s a crazed axe murderer on the loose on the same evening; it never rains but it pours. After we see the worst happen with respect to both of these events, we cut to 1986. The weird, weird world of US college life is getting into full swing for that academic year, including the traditions of potential fraternity and sorority house inmates undertaking dangerous/stupid things as ‘pledges’ (seriously, America: why do you do it to yourselves?) Two outsiders, ‘dorks’ Chris (Jason Lively) and best friend J. C. (Steve Marshall) are doing their best to navigate through this new, potentially fraught social situation, as well as hankering after beautiful, probably inaccessible girls like Cynthia Cronenberg (Jill Whitlow). Sadly for them, it turns out that to get anywhere either socially or romantically, they’ll have to actually sign up for a pledge of their own – as set by a group of probable future Republican party candidates, who make it good and difficult. Their task? To break out a cryogenically frozen corpse from the local hospital. Night of the Creeps also boasts what I think we can now call a classic Dekker script, somewhere between plausible and humane in places, obviously crafted in others, with catchphrases and black humour throughout. It’s a film where you can laugh at the exchanges between Chris and J.C, but also get a true sense of their friendship, right down to a genuine feeling of pity when they’re torn apart. Tom Atkins, one of the most recognisable and beloved figures in cult cinema, is at his best here (in what he’s termed his own favourite film which he appeared in). He’s such a vivid character, but again, when not camping it up and yelling “Thrill me!” down the telephone, the guy can really act. I think that’s it: up against these preposterous turns of events, all of the cast do such a great job, and lend a kind of deserved gravitas to their roles. Their respect for the subject matter makes the storytelling all the more entertaining. Sure, the end of the film (with this ending) tantalises for a sequel which never came, but Night of the Creeps is more than sufficient. As pure entertainment, I can’t fault it.

Night of the Creeps also boasts what I think we can now call a classic Dekker script, somewhere between plausible and humane in places, obviously crafted in others, with catchphrases and black humour throughout. It’s a film where you can laugh at the exchanges between Chris and J.C, but also get a true sense of their friendship, right down to a genuine feeling of pity when they’re torn apart. Tom Atkins, one of the most recognisable and beloved figures in cult cinema, is at his best here (in what he’s termed his own favourite film which he appeared in). He’s such a vivid character, but again, when not camping it up and yelling “Thrill me!” down the telephone, the guy can really act. I think that’s it: up against these preposterous turns of events, all of the cast do such a great job, and lend a kind of deserved gravitas to their roles. Their respect for the subject matter makes the storytelling all the more entertaining. Sure, the end of the film (with this ending) tantalises for a sequel which never came, but Night of the Creeps is more than sufficient. As pure entertainment, I can’t fault it. The Western, pioneered by the likes of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah, is a format which has spawned cinema around the world, with recognisably Western-style filmmaking appearing everywhere, even in the likes of the Convict Scorpion films in Japan during the 70s. However, I think it’s probably fair to say that South Africa isn’t greatly known for Westerns. Given the Western’s emphasis on lawlessness and vigilante justice, though, it’s clear why director Michael Matthews decided to give it a whirl in this setting. That this is his first feature is incredible; the resulting film, Five Fingers for Marseilles, eight years in the making, is a skilled piece of work, if a challenging, weighty experience.

The Western, pioneered by the likes of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah, is a format which has spawned cinema around the world, with recognisably Western-style filmmaking appearing everywhere, even in the likes of the Convict Scorpion films in Japan during the 70s. However, I think it’s probably fair to say that South Africa isn’t greatly known for Westerns. Given the Western’s emphasis on lawlessness and vigilante justice, though, it’s clear why director Michael Matthews decided to give it a whirl in this setting. That this is his first feature is incredible; the resulting film, Five Fingers for Marseilles, eight years in the making, is a skilled piece of work, if a challenging, weighty experience. All of this is convincingly, and very movingly carried on the shoulders of the lead actor Vuyo Dabula as Tau, a man who displays a staggering gamut of emotions whilst barely saying a word; he oscillates between rare moments of joy and desperation, and it’s a very absorbing performance throughout. But he is ably supported by his old friends, in particular Zeto Dlomo as the gang’s old sweetheart Lerato, now a grown woman desperate for life to improve for her and her ailing father. A devastating musical score pulls on the heartstrings even more, with its long, low incidental notes underscoring the tragedy unfolding on-screen. I do feel that the film plays out as a tragedy in many respects, because for all of the nods to the great Westerns of the past, there’s an overarching dour atmosphere here of impending doom, right from the start, where any expectations we might have for a gang of children on our screens are ultimately taken in a different direction; I don’t think you ever feel that people are going to ride off happily into the sunset. The film looks spectacular, an engaging visual blend of landscape and townscape, myth and reality – with certain characters, such as the ominous gang leader, seeming almost supernatural in some scenes. Commentary on the presence of ‘the land’ as the ultimate arbiter of man’s affairs even leans towards folklore, albeit ultimately played out in gritty, hard-hitting and realist fashion. It’s also interesting to get a film which plays out in a variety of different languages: English is a lingua franca, but the characters code-switch throughout, using Sotho and Xhosa in turn, too. This helps to ground the action in its setting, as well as bringing native languages to the fore, as spoken by the people who live in these areas.

All of this is convincingly, and very movingly carried on the shoulders of the lead actor Vuyo Dabula as Tau, a man who displays a staggering gamut of emotions whilst barely saying a word; he oscillates between rare moments of joy and desperation, and it’s a very absorbing performance throughout. But he is ably supported by his old friends, in particular Zeto Dlomo as the gang’s old sweetheart Lerato, now a grown woman desperate for life to improve for her and her ailing father. A devastating musical score pulls on the heartstrings even more, with its long, low incidental notes underscoring the tragedy unfolding on-screen. I do feel that the film plays out as a tragedy in many respects, because for all of the nods to the great Westerns of the past, there’s an overarching dour atmosphere here of impending doom, right from the start, where any expectations we might have for a gang of children on our screens are ultimately taken in a different direction; I don’t think you ever feel that people are going to ride off happily into the sunset. The film looks spectacular, an engaging visual blend of landscape and townscape, myth and reality – with certain characters, such as the ominous gang leader, seeming almost supernatural in some scenes. Commentary on the presence of ‘the land’ as the ultimate arbiter of man’s affairs even leans towards folklore, albeit ultimately played out in gritty, hard-hitting and realist fashion. It’s also interesting to get a film which plays out in a variety of different languages: English is a lingua franca, but the characters code-switch throughout, using Sotho and Xhosa in turn, too. This helps to ground the action in its setting, as well as bringing native languages to the fore, as spoken by the people who live in these areas. Spoiler warning.

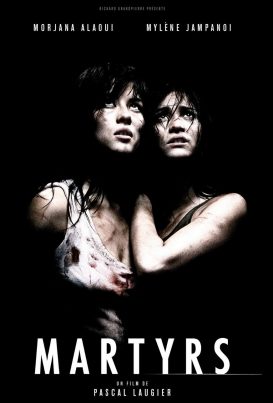

Spoiler warning. I reference the ‘cut-and-shut’ idea above because one criticism of Martyrs is how it shifts from the intimation of supernatural horror to something altogether different in its second act, as the film’s supernatural content gets closed off not just to the audience, but also to the people trying to coax supernatural evidence out of their victim. Lucie’s campaign of vengeance (abuse-revenge rather than rape-revenge) is punctuated by visions of a tortured girl rendered almost demonic by her determination to attack Lucie. We are left wondering, at this stage at least, whether Lucie is undergoing a pure hallucination: the gravity of the attacks on her push the idea of this being ‘all in her head’ about as far as they could conceivably go. In this respect, Martyrs seems to draw together a lot of the quite disparate threads which were drifting along together in horror cinema at the time, and it does so in a way which is quite unique and challenging.

I reference the ‘cut-and-shut’ idea above because one criticism of Martyrs is how it shifts from the intimation of supernatural horror to something altogether different in its second act, as the film’s supernatural content gets closed off not just to the audience, but also to the people trying to coax supernatural evidence out of their victim. Lucie’s campaign of vengeance (abuse-revenge rather than rape-revenge) is punctuated by visions of a tortured girl rendered almost demonic by her determination to attack Lucie. We are left wondering, at this stage at least, whether Lucie is undergoing a pure hallucination: the gravity of the attacks on her push the idea of this being ‘all in her head’ about as far as they could conceivably go. In this respect, Martyrs seems to draw together a lot of the quite disparate threads which were drifting along together in horror cinema at the time, and it does so in a way which is quite unique and challenging. Similarly, the world we continue to occupy is all too ready to grant us protracted violence and dismal conclusions, with our own spectres ready to rise up and greet us. Dig just a little, and you can find footage of human beings still being burned alive or executed for some thinly hopeful spiritual reason or transgression; if Martyrs’ most appalling scenes once seemed too extreme or absurd, then do they now, under a continued torrent of evidence which we have to work to avoid, rather than seek out? Any internet search does it. And, as our population ages (it’s notable that so many of the seekers in Martyrs are elderly) we are going to be brought up against the all-but-certain nothingness at the end of it all. As for networks of people tormenting and abusing children – well, it’s notable that the word ‘historic’ has now undergone a kind of pejoration, so often have we heard it in its new guise; it’s now often wedded to cases of organised child abuse going back decades, happening just beneath the surface of the everyday. In effect, life can be wonderful, but for so many it can be a bleak and thankless existence, and the film encapsulates perfectly that compulsion to find purpose, by whatever horrible means. I don’t mean to be trite here: Martyrs is, after all, just a film, but perhaps it has taken root because of the way it cast about for unpalatable elements in the real world and condensed them into a startling and – whatever your take on it – unforgettable horror movie.

Similarly, the world we continue to occupy is all too ready to grant us protracted violence and dismal conclusions, with our own spectres ready to rise up and greet us. Dig just a little, and you can find footage of human beings still being burned alive or executed for some thinly hopeful spiritual reason or transgression; if Martyrs’ most appalling scenes once seemed too extreme or absurd, then do they now, under a continued torrent of evidence which we have to work to avoid, rather than seek out? Any internet search does it. And, as our population ages (it’s notable that so many of the seekers in Martyrs are elderly) we are going to be brought up against the all-but-certain nothingness at the end of it all. As for networks of people tormenting and abusing children – well, it’s notable that the word ‘historic’ has now undergone a kind of pejoration, so often have we heard it in its new guise; it’s now often wedded to cases of organised child abuse going back decades, happening just beneath the surface of the everyday. In effect, life can be wonderful, but for so many it can be a bleak and thankless existence, and the film encapsulates perfectly that compulsion to find purpose, by whatever horrible means. I don’t mean to be trite here: Martyrs is, after all, just a film, but perhaps it has taken root because of the way it cast about for unpalatable elements in the real world and condensed them into a startling and – whatever your take on it – unforgettable horror movie. You know a film still has something, however many years pass, when you consider what would happen to it if it was pitched today. So at a guess, and alongside most of the best horror and exploitation films ever made, a film which involves exploding drug addicts and reanimated hookers via bad science would be unlikely to get a pass – at least, not from anyone with a considerable budget or say-so. This is the very basic plot of Frankenhooker (1990), a film which feels like it nicely rounds off Frank Henenlotter’s period of film releases during the 1980s, albeit that Basket Case 3

You know a film still has something, however many years pass, when you consider what would happen to it if it was pitched today. So at a guess, and alongside most of the best horror and exploitation films ever made, a film which involves exploding drug addicts and reanimated hookers via bad science would be unlikely to get a pass – at least, not from anyone with a considerable budget or say-so. This is the very basic plot of Frankenhooker (1990), a film which feels like it nicely rounds off Frank Henenlotter’s period of film releases during the 1980s, albeit that Basket Case 3  By adulterating crack cocaine, of course. Once inhaled, it will cause the women to explode. He knows this because he practices on a guinea pig. Although he has a moment of conscience which almost prevents this from happening, gladly it does happen, in one of the most absurd, brilliantly excessive sequences ever filmed. Oh Frank Henenlotter, how we love you for it. But actually getting the parts is only the beginning. Jeffrey next has to assemble them, do the obligatory lightning reanimation thing (as much as a staple of Frankenstein movies as the monster itself) and then hope against hope that his deceased fiancee is mentally coherent and even grateful that he’s rebuilt her out of a panoply of prostitutes’ limbs, all selected because he likes them better than her own! What woman wouldn’t be charmed and flattered, I ask you?

By adulterating crack cocaine, of course. Once inhaled, it will cause the women to explode. He knows this because he practices on a guinea pig. Although he has a moment of conscience which almost prevents this from happening, gladly it does happen, in one of the most absurd, brilliantly excessive sequences ever filmed. Oh Frank Henenlotter, how we love you for it. But actually getting the parts is only the beginning. Jeffrey next has to assemble them, do the obligatory lightning reanimation thing (as much as a staple of Frankenstein movies as the monster itself) and then hope against hope that his deceased fiancee is mentally coherent and even grateful that he’s rebuilt her out of a panoply of prostitutes’ limbs, all selected because he likes them better than her own! What woman wouldn’t be charmed and flattered, I ask you? For a film about a hybrid undead prostitute running amok on New York’s streets, and for all that it had an exceptionally modest box office reception, Frankenhooker seems like Henenlotter’s most accessible film of the bunch. Hear me out: regardless of the subject matter, it doesn’t feel quite as skeezy as Basket Case or Brain Damage, despite sharing a lot of shooting locations and being made within a few short years. The NY streets are still sleazy but brighter, less oppressive-feeling somehow, and besides the film veers between there and the leafy suburbia over the bridge, as well as feeling a lot more modern with its TV talk show skits and the Never Say No song, which pokes fun at a lot of late 80s social anxieties. With the exception of what I’ll refer to as the ‘fridge scene’, the body horror is less grotesque here, too; Elizabeth has a few stitches, but otherwise she certainly doesn’t look as grim or warped as Belial or Elmer. It’s also a rather bloodless film, even oddly so, thanks to the novel limb-gathering technology Jeffrey deploys – which cauterises the wounds rather well. The horror overall is overshadowed by what creeps into soft-core territory in places, perhaps giving us a peek at the kind of horror/exploitation ratio Henenlotter most prefers. All in all, Frankenhooker keeps things cartoonish, and never quite as dark as either Basket Case or Brain Damage. It’s very much its own beast with its own laugh-out-loud atmosphere and outlandish, fleshly excess, and it’s yet another enjoyable foray into a world where bodily integrity spoils the fun.

For a film about a hybrid undead prostitute running amok on New York’s streets, and for all that it had an exceptionally modest box office reception, Frankenhooker seems like Henenlotter’s most accessible film of the bunch. Hear me out: regardless of the subject matter, it doesn’t feel quite as skeezy as Basket Case or Brain Damage, despite sharing a lot of shooting locations and being made within a few short years. The NY streets are still sleazy but brighter, less oppressive-feeling somehow, and besides the film veers between there and the leafy suburbia over the bridge, as well as feeling a lot more modern with its TV talk show skits and the Never Say No song, which pokes fun at a lot of late 80s social anxieties. With the exception of what I’ll refer to as the ‘fridge scene’, the body horror is less grotesque here, too; Elizabeth has a few stitches, but otherwise she certainly doesn’t look as grim or warped as Belial or Elmer. It’s also a rather bloodless film, even oddly so, thanks to the novel limb-gathering technology Jeffrey deploys – which cauterises the wounds rather well. The horror overall is overshadowed by what creeps into soft-core territory in places, perhaps giving us a peek at the kind of horror/exploitation ratio Henenlotter most prefers. All in all, Frankenhooker keeps things cartoonish, and never quite as dark as either Basket Case or Brain Damage. It’s very much its own beast with its own laugh-out-loud atmosphere and outlandish, fleshly excess, and it’s yet another enjoyable foray into a world where bodily integrity spoils the fun. Anthology films – often three short tales with a common framework – are nothing new, even if the format isn’t used all that often today. We have, however, seen some interesting variations on the anthology film in recent years, perhaps most notably with The ABCs of Death in 2012, which made a minor stir and spawned a second edition. Certainly, what this anthology showed was that there’s acres of potential in the idea that a film can comprise several shorter chapters, whether or not these chapters are linked in the way that, say, the old Amicus portmanteau films were. As we know, sometimes a film’s cardinal sin is overstaying its welcome, or stretching a meagre idea over ninety minutes. Short filmmakers can’t get away with that. So, I was very optimistic when I came to watch Blood Clots, an anthology film which has taken the unusual step of compiling seven horror tales. Whilst the stories themselves aren’t linked, what they have in common is a punchy, decisively entertaining approach and enough variety to please any number of viewers.

Anthology films – often three short tales with a common framework – are nothing new, even if the format isn’t used all that often today. We have, however, seen some interesting variations on the anthology film in recent years, perhaps most notably with The ABCs of Death in 2012, which made a minor stir and spawned a second edition. Certainly, what this anthology showed was that there’s acres of potential in the idea that a film can comprise several shorter chapters, whether or not these chapters are linked in the way that, say, the old Amicus portmanteau films were. As we know, sometimes a film’s cardinal sin is overstaying its welcome, or stretching a meagre idea over ninety minutes. Short filmmakers can’t get away with that. So, I was very optimistic when I came to watch Blood Clots, an anthology film which has taken the unusual step of compiling seven horror tales. Whilst the stories themselves aren’t linked, what they have in common is a punchy, decisively entertaining approach and enough variety to please any number of viewers. Time to Eat is next, a short, sweet spin on the ‘something in the basement’ idea, followed by Still, which is a genius idea whereby a street performer – you know, the guys who stand stock still in city centres for the edification of tourists – is stuck, rooted to the spot during an incredibly gory zombie outbreak. We’re treated to his internal monologue as all of this unfolds, and this is a film both very camp and very slick in its delivery. Hellyfish has a daft central idea worthy of SyFy, as the unlikely couple of a Russian femme fatale and an Iranian jihadist look for a missing H-bomb off the coast of the US. We all know what ‘nuclear’ means where there’s any manner of ecosystem around, so before long this goofy skit on ‘B’ movies old and new winds up terrorising the beach with…well, nothing more needs to be said, I’m sure.

Time to Eat is next, a short, sweet spin on the ‘something in the basement’ idea, followed by Still, which is a genius idea whereby a street performer – you know, the guys who stand stock still in city centres for the edification of tourists – is stuck, rooted to the spot during an incredibly gory zombie outbreak. We’re treated to his internal monologue as all of this unfolds, and this is a film both very camp and very slick in its delivery. Hellyfish has a daft central idea worthy of SyFy, as the unlikely couple of a Russian femme fatale and an Iranian jihadist look for a missing H-bomb off the coast of the US. We all know what ‘nuclear’ means where there’s any manner of ecosystem around, so before long this goofy skit on ‘B’ movies old and new winds up terrorising the beach with…well, nothing more needs to be said, I’m sure. If you freeze-frame in the opening reels of Basket Case 2, a curious thing happens. You can almost – almost – sense the utter surprise on Frank Henenlotter’s part that he’s making a sequel to his surprise grindhouse hit at all.

If you freeze-frame in the opening reels of Basket Case 2, a curious thing happens. You can almost – almost – sense the utter surprise on Frank Henenlotter’s part that he’s making a sequel to his surprise grindhouse hit at all. Made in the same year as the uproarious Frankenhooker, Basket Case 2 feels like a perfect blend between opportunism and kicking back – grabbing the chance to make a sequel while the going’s good, but not labouring under any illusions either. Henenlotter is clearly in a mind to go to town on the special effects here, with the result that the film feels to be around 60% latex, and there’s a whole host of new characters being given screen time. Eerily, Belial looks a hell of a lot more like Kevin Van Hentenryck in this incarnation, which somehow makes him look even nastier, even though Van Hentenryck himself has a perfectly amiable face: that lends itself very well to the whole good twin/bad twin thing. In terms of subject matter, things feel a lot more jokey overall in Basket Case 2, but there are still characteristically grim moments. This isn’t a simple moral high ground thing where the poor put-upon ‘freaks’ are mistreated; they aren’t terribly nice to outsiders either, maintaining what seems to be an unspoken Henenlotter mantra: “most people are assholes”, whether or not they have the conventional two arms, two legs, one head.

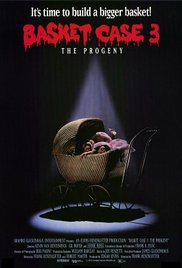

Made in the same year as the uproarious Frankenhooker, Basket Case 2 feels like a perfect blend between opportunism and kicking back – grabbing the chance to make a sequel while the going’s good, but not labouring under any illusions either. Henenlotter is clearly in a mind to go to town on the special effects here, with the result that the film feels to be around 60% latex, and there’s a whole host of new characters being given screen time. Eerily, Belial looks a hell of a lot more like Kevin Van Hentenryck in this incarnation, which somehow makes him look even nastier, even though Van Hentenryck himself has a perfectly amiable face: that lends itself very well to the whole good twin/bad twin thing. In terms of subject matter, things feel a lot more jokey overall in Basket Case 2, but there are still characteristically grim moments. This isn’t a simple moral high ground thing where the poor put-upon ‘freaks’ are mistreated; they aren’t terribly nice to outsiders either, maintaining what seems to be an unspoken Henenlotter mantra: “most people are assholes”, whether or not they have the conventional two arms, two legs, one head. Basket Case 3: The Progeny was made the following year, and wrapped within a month. Being made so close to the last film, it hardly needs the lengthy flashback which harks back to BC2, but what this does make clear is that the memorable sex scene sequence isn’t forgotten yet; it’s going somewhere. We find out that Eve (Belial’s girlfriend) is in the family way, no one’s quite sure what her birth will entail, and Duane has meanwhile been locked in a padded cell for trying to re-attach his brother. These are, by the way, not words you’d ordinarily find yourself typing.

Basket Case 3: The Progeny was made the following year, and wrapped within a month. Being made so close to the last film, it hardly needs the lengthy flashback which harks back to BC2, but what this does make clear is that the memorable sex scene sequence isn’t forgotten yet; it’s going somewhere. We find out that Eve (Belial’s girlfriend) is in the family way, no one’s quite sure what her birth will entail, and Duane has meanwhile been locked in a padded cell for trying to re-attach his brother. These are, by the way, not words you’d ordinarily find yourself typing. Each successive Basket Case film seems to reach a little higher, from an already lunatic premise, to new heights of creature FX and bizarre ways for these FX to get invoked. For instance, the birth sequence in BC3 is a fun exercise in excess, throwing in catchphrases like “ovarian ovation”, then matching this with a dream sequence for Belial (reprised after the end credits). The last visit to the world of Belial and Duane shows them not as outsiders, railing against the world, but somewhat bewildered members of an extended family group, dealing with family issues. In this respect, BC3 couldn’t be more different to BC; the fact that all of the planned gore was more or less excised from BC3 at the request of the producers further alters the film’s tone, making it generally more playful and allowing it to give the odd nod to other films (the ‘mad inventor’ shtick had just done a turn in Frankenhooker; Belial’s contraption also looks a little like a certain scene in Aliens, though perhaps that’s just me, going a little mad here?)

Each successive Basket Case film seems to reach a little higher, from an already lunatic premise, to new heights of creature FX and bizarre ways for these FX to get invoked. For instance, the birth sequence in BC3 is a fun exercise in excess, throwing in catchphrases like “ovarian ovation”, then matching this with a dream sequence for Belial (reprised after the end credits). The last visit to the world of Belial and Duane shows them not as outsiders, railing against the world, but somewhat bewildered members of an extended family group, dealing with family issues. In this respect, BC3 couldn’t be more different to BC; the fact that all of the planned gore was more or less excised from BC3 at the request of the producers further alters the film’s tone, making it generally more playful and allowing it to give the odd nod to other films (the ‘mad inventor’ shtick had just done a turn in Frankenhooker; Belial’s contraption also looks a little like a certain scene in Aliens, though perhaps that’s just me, going a little mad here?) When I heard that Mara was a horror story invoking sleep paralysis as a key element of its plot, as a sufferer I was immediately interested. Sleep paralysis is well understood in the modern age, just as sleep and dreams are generally, but anyone who has ever had a significant nightmare, or a waking nightmare will know that reason and rationality are furthest from your mind when undergoing this kind of terror; therefore, these experiences remain ripe for solid on-screen explorations, offering lots of potential. Happily, director Clive Tonge and writer Jonathan Frank have shown themselves more than up to that task in Mara, a film which weaves a mythology around sleep paralysis, but balances this against far more grounded and mundane preoccupations which trouble people in their sleep.

When I heard that Mara was a horror story invoking sleep paralysis as a key element of its plot, as a sufferer I was immediately interested. Sleep paralysis is well understood in the modern age, just as sleep and dreams are generally, but anyone who has ever had a significant nightmare, or a waking nightmare will know that reason and rationality are furthest from your mind when undergoing this kind of terror; therefore, these experiences remain ripe for solid on-screen explorations, offering lots of potential. Happily, director Clive Tonge and writer Jonathan Frank have shown themselves more than up to that task in Mara, a film which weaves a mythology around sleep paralysis, but balances this against far more grounded and mundane preoccupations which trouble people in their sleep. Something else which is very interesting in this film comes via another of its core plot developments – that Matthew Wynsfield somehow puts himself in danger by seeking help for his sleep paralysis issues. Rather than that vague modern panacea of ‘support’ ridding people of their problems, here in the form of a support group, in Mara it exposes people to more harm. In effect, a potential cure, one we believe in on an almost religious scale today, lays people bare to a threat, which itself stems from an innovative blend of folklore, the supernatural, and something between a good old-fashioned curse and psychological breakdown. It’s pessimistic in the extreme, and it’s handled with genuine ingenuity here.

Something else which is very interesting in this film comes via another of its core plot developments – that Matthew Wynsfield somehow puts himself in danger by seeking help for his sleep paralysis issues. Rather than that vague modern panacea of ‘support’ ridding people of their problems, here in the form of a support group, in Mara it exposes people to more harm. In effect, a potential cure, one we believe in on an almost religious scale today, lays people bare to a threat, which itself stems from an innovative blend of folklore, the supernatural, and something between a good old-fashioned curse and psychological breakdown. It’s pessimistic in the extreme, and it’s handled with genuine ingenuity here.