For the past few years, Warped Perspective has been fortunate enough to cover the Fantasia International Film Festival remotely and, every year, it’s a high point in the film lover’s calendar. This year looks to be no different. Whilst the availability for press coverage varies, Warped Perspective has high hopes that we may get a sneak peek at some of the following titles: we’ll certainly be looking out for them. In any case, if you’re fortunate enough to be going to the festival in person, or if you just want some pointers for the autumn festival season (Fantasia often leads the way on genre releases which surface in other fests later in the year) then here’s a few titles to look out for:

In Our Blood

Found footage is a divisive subject at the site, for writers and for readers, but – love it or hate it – In Our Blood sounds like an intriguing spin on the style, coming as the first FF film from an already renowned documentarian, the Oscar-nominated Pedro Kos. In the film, a filmmaker called Emily Wyland (Brittany O’Grady, White Lotus) teams up with a cinematographer, Danny, to make a film about reuniting with her mother after a long hiatus in their relationship: however, the original plan for the film gets disrupted when her mother suddenly goes missing: now it’s a mystery about a missing person, and Emily and Danny must piece together the clues before it’s too late.

The Silent Planet

Science fiction has, overall, sacrificed some of its bombast in recent years: modern sci-fi often scales back the technology and the spacecraft and its other flashier hallmarks, electing instead to ponder deeper philosophical ideas, using the extraordinary situations and possibilities afforded by sci-fi to do so. This brings us neatly to The Silent Planet, directed by Jeffrey St. Jules. The setting here is a penal planet, and two prisoners sent there to mine the planet’s resources discover that they have a deep-seated connection – one which threatens and complicates their relationship, and their time in this faraway place. In the film, concepts of truth, meanings and responsibilities are explored via a whimsical, surrealist style.

Black Eyed Susan

AI and its increasing presence in the creative industries, not to mention in the world at large, is an ever-evolving source of anxiety these days; as such, it’s little surprise that horror and genre cinema – always ready to face and twist our deepest anxieties into new shapes and forms – has come up with the queasy, and probably five-years-hence storyline behind Black Eyed Susan. Desperate for work, Derek (Damian Maffei) accepts a role with a shady tech start-up, working intimately with ‘Susan’ (Yvonne Emilie Thälker in a powerful debut role), a BDSM sex doll which learns via sexual pain and punishment. The focus is different to The Silent Planet but again, here we have AI and sci-fi coming together to ask big questions about what it means to be human – and humane, in this film with its pitch-black, unsettling core. It’s also edifying to learn that the maestro of movie soundtracks, Fabio Frizzi, is back at work on the score to this film.

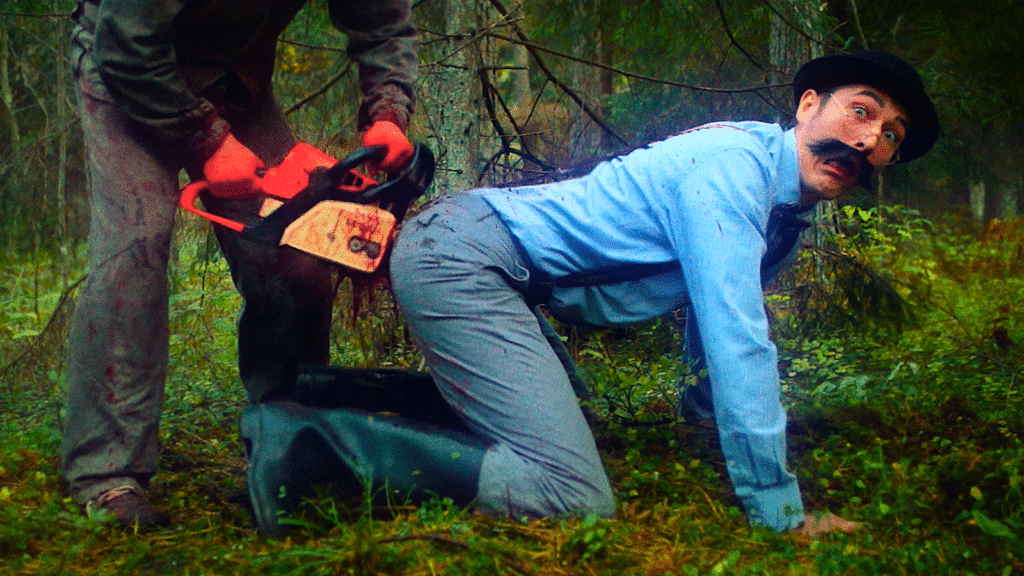

Chainsaws Were Singing

Whilst my personal experience of Estonian cinema is quite limited, the zany world-building of Kratt (which screened at the festival back in 2021) was a worthy, fun introduction, a film which showcases a bland of styles and genres to good effect. Sounding to be a similar kind of blend, Chainsaws Were Singing mixes slapstick, splatstick and – well, chainsaws, in a bizarre musical mash-up by director Sander Maran. Maran does the lot here, from direction to editing to writing the entire musical score, offering up a madcap palate-cleanser which neither takes itself too seriously, nor scrimps on the ludicrous chainsaw-based violence. If you liked Cannibal! The Musical, then this one’s for you.

Other highlights:

- Steppenwolf: a bleak, post-Soviet Kazakh spin on the classic Hermann Hesse prayer to nihilism and self…

- House of Sayuri: J-Horror is back (if it ever went away) but now it’s both self-referential and profoundly surprising…

- South Korean movie The Tenants charts the course of property insecurity across the globe, with this macro storyline of a pair of lodgers whose strange behaviour escalates into a nightmare for their beleaguered landlord/housemate…

- Párvulos -a gruelling Mexican dystopian horror about three brothers living together in a remote cabin. Hidden in the basement is a terrible secret which, as kids do, they have learned to accept but – the worst is yet to come. Seven years in the making, Isaac Ezban’s feature is likely to bring shock and awe to the festival.

- Timestalker sees director Alice Lowe take comic aim at the heart of the romcom genre, in her new story of a woman seeking out the (presumed) love of her life across time…

Watch out for our coverage coming very soon, and in the meantime, head over to the festival’s official website for a look at what else is on offer.