By Guest Contributor Helen Creighton

Game of Thrones has finally ended, and not in a way everyone found entirely satisfactory.

This is nothing new in television; there’s a history of beloved, long-running shows dropping final seasons or finales that leave their audiences feeling cheated. Take the long-running 80s hospital drama St. Elsewhere, concluded with the abrupt and unlikely revelation the entire show was a figment of an autistic boy’s imagination, and took place in a snow globe. The last season of the hugely successful sitcom Roseanne upped the ante by asking audiences to believe the previous nine seasons about the comedic trials and tribulations of a lovable working-class family were merely a pathetic work of fiction written by a depressed, widowed and financially-ruined Roseanne. Like most clever-clever metafiction pasted onto perfectly functional stories, let alone long-running comedies, this proved less than wildly popular. Then there was the more recent and hugely popular Lost; years of mystery piled upon mystery revealed to be simply red herring piled upon on red herring and a revelation that the entire story took place in – literally – Purgatory was generally rejected as rather unsatisfying by those who had tuned in for six years previously. Amazingly, that kind of ‘fooled you! it was all nonsense, all along!’ bait and switch just doesn’t play well with audiences.

Hell, fan engagement and disappointment with fiction goes back a long way further than the TV age. People have always engaged emotionally with good stories. It’s not just Game of Thrones that had people speculating on probable deaths. In 1841, when the newspapers carrying the final chapter of Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop arrived on a ship in New York, people following the saga crowded the harbour and shouted to the sailors, “Is Little Nell dead?” so beloved was the character in the hearts of the general public, in an age where nobody cared about spoilers. When she was revealed to be indeed (spoiler!) dead, it evoked outrage. Letters were written to the newspapers. Reputed judges were found in their chambers, weeping over the book. The Irish politician Daniel O’Connell declared himself so outraged by Nell’s death that he flung the book out of the window of the train he was travelling on and declared the writer incompetent. Oscar Wilde waded in some decades later to declare the death should move anyone to tears .. . of laughter, which just goes to show trolling also existed a long time before the internet.

Certainly, bitching about fiction – and being inspired by it, and bitching about it because we care about it, goes back to the ancients. We care about stories – about imaginary people and places – because they help us make sense of ourselves and the world. Stories define nations and people; they forge identities. On a more prosaic level, investing hours and a great deal of thought and emotion in a thing tends to make people protective of a thing, and the flipside of excitement is disappointment.

So it’s not actually weird for people to get a bit upset when they feel a good story has been let down and metaphorically want their money back, throw their remote at the telly in the manner of the aforementioned Mr. O’Connell throwing books off a train or just take to the internet to bitch and meme a bit (hello!).

So, back to Game of Thrones and its last hoorah. I present the following with the proviso that I have not spent eight years finding major fault with the show; I thought it was near-flawless for the first four seasons, went south in season five (those live-action Bratz Doll versions of the Sand Snakes didn’t seem to belong in the same universe as the other characters for starters) and six (again, the nonsensical Dorne plot which is really enough for an article all of its own given it replaced an actual, usable and better plot from the books, but hey, the showrunner wanted to work with the actress Indira Varma who played Ellaria Sand, and jettisoned Alexander Siddig’s character Prince Doran Martell to write some nonsense around her), and started to show serious narrative problems with the truncated season seven, but generally I was galloping along relatively happily with it for the most part and very excited for the final run.

So this isn’t about simply never being pleased with the show or about attachment to particular characters whose arcs went ways I didn’t care for, or throwing my toys out of the pram the moment I found something I didn’t like. It’s about watching an epic come to an conclusion that not only doesn’t live up to its promise, but presents some of the worst writing of the entire run in what should have been its finest hour. The expectation, despite some serious bumps along the way, was a pay-off as complex and interesting as what had gone before; what we got what a series of poorly-connected plot points, meaningless ‘subversion’, plot holes and character regression all of which seem to add up to more of a lazy ‘fuck you’ than a satisfying conclusion.

Egos abound in showbusiness where actors and showrunners like to pretend audience opinions matter deeply when those opinions are overwhelmingly positive, and suddenly cease to matter when negative. It’s a business where everyone wants to believe they deserve the bouquets, but never the brickbats. Well, in my view the brickbats for this season are fully deserved and nearly all of them have been aimed squarely at one single aspect of the show – the writing…

Let’s start with Daenerys. Daenerys Stormborn of House Targaryen, the First of Her Name, Queen of the Andals and the First Men, Protector of the Seven Kingdoms, the Mother of Dragons, the Khaleesi of the Great Grass Sea, the Unburnt, the Breaker of Chains.Which, after episode five of season eight, can be basically shortened to, ‘Hitler’. Her descent into blood and fire Targaryen Nazi, or shall we more tactfully say ‘potential tyrant’ (Adolf Targaryen?) was not without foreshadowing.

She’s always been capable of violence, as indeed are pretty much all the characters in Game of Thrones. Even Sansa eventually coldly sits and tortures a man (deservedly) to death. It’s a horribly violent world where the strongest prevail and rule, the throne is taken via war when primogeniture fails, and where justice is retributive and punitive, never rehabilitative. Yes, she had declared her intent to ‘break the wheel’ of wars, successions and oppressions, which some took as her intent to foist some pleasant form of social democracy on Westeros via dragon power, but I always saw as rather ominous, Tito-esque kind of viewpoint. Can’t oppress each other when you’ve got one big scary tyrant to oppress the whole lot of you equally, right? And of course, she has all the lofty entitlement of an aristocrat.

Yet she also showed an instinct to protect the weak; as Khaleesi, she prohibited the rape of captives by the Dothraki. She chained up two of her dragons – her ‘children’ – in a dungeon, when the third went rogue and incinerated a shepherd’s child in Mereen. She refused to open the fighting pits at Mereen despite it being a popular move with the citizenry because she hated the violence. She spent a deal of time freeing slaves from their shackles and when she crucified 143 ‘masters’ it was in response to their crucifying the same number of children along the road to Mereen to taunt her. She burned Vaes Dothrak to the ground, but only after the Khals declared their intention to rape her to death, using horses if they couldn’t complete the job themselves.

Yes, she’s from a line known for their tendency toward madness. Her own father had succumbed to it, but is described as having taken nearly ten years for the symptoms to go from increasingly poor hygiene and paranoia, to sadism and murder, to eventually deciding to annihilate the entire city and everyone in it with wildfire. Ten years.

So you have to give me more than one single episode between Daenerys feeling increasingly frustrated with the North for not falling at her feet, Jon getting cold feet about their incestuous relationship, a dragon dying due to her own stupidity (framed by Benioff and Weiss, showrunners as her ‘kinda forgetting’ the Iron Fleet existed) and the death of a friend to going full Russian Front on King’s Landing innocents, not before, but after the city surrendered to her. Her mutterings as having to ‘rule through fear’ come across less as encroaching madness and more as a policy decision made through little more than ego, pique and impatience together with the rationalisation, not entirely uncommon throughout history, that the ends justify the means. The post-devastation Little Nuremberg moment (dragon wings substituting for cathedrals of light, I guess, and a really nice effect actually) in the finale just came off as oddly campy, ‘turn up the evil to eleven’ territory while Grey Worm doing an ISIS-style execution scene fresh off the blocks was a bit much.

Given a full season at least of a gradually decaying personality, the ‘magical mad queen’ storyline could have been entirely convincing and actually fascinating; Tolkein’s Galadriel if she had chosen to keep the Ring and become corrupted by its power. The tension would have built toward more interesting and hopefully, more intelligent betrayals. Varys, master of spies and whispers, writing a plain text betrayal letter to potential allies? Come on. This man survived years of Mad King Aerys and then the erratic and sadistic King Joffrey without a scratch. As it was, her sudden attack of the genocides came off as just another in a line of pop-up ‘subversion’ of audience expectations that had ironically become entirely predictable in a thoroughly rushed season where getting from A to B in as little time as possible was the point, character and in-world reality be damned.

Subverting expectations. Yeah. Here’s the thing. In Television Land, though, it’s possible to become a victim of your own success and the carefully-plotted genre subversions (such as setting up a protagonist who is killed before the end of the first season) eventually seemed to set up an expectation for the show to keep surprising the viewer for the sake of surprise alone, not because it makes sense of anything or follows on from previous plot developments. Take the the killing of the Night King by Arya Stark, a decision made by the showrunners a couple of years previously for the sole reason of the old ‘subversion of expectations’. Subversion for the sake of simple shock-surprise is not subversion. It’s just a cop-out.

Other characters suffered from as similarly abrupt and unsatisfying turnarounds as Daenerys. Jon Snow, after being given little to really do all season after his arc was terminated to hand Arya the big kill in The Long Night, wanders around like an increasingly confused puppy, is persuaded by Tyrion (who seems to have all the big ideas in this show now) to murder Daenerys and carries out the order within the matter of a few minutes’ screen time. This, despite spending much of the episode convinced she has really done nothing wrong. Arya, after spending years being obsessively and actively murderous, is convinced by The Hound to drop her pursuit of violence after a few seconds of consideration in the thick of the massacre at King’s Landing. Meanwhile, her endless episodes of Faceless Man training proved of zero use in the entire final season apart from some admittedly impressive staff fighting – the last time we see her use another face is to serve up some relatively pointless House Frey revenge porn in season seven.

Jamie Lannister spent years slowly being humbled by experience and redeemed by his actions, only to be the fool that returns to his folly as the dog returns to his vomit – the vomit in this case being his sister and their incestuous relationship, but only after a really odd 21st century-style one night stand with Brienne of Tarth. Classic tragedy, I suppose, a man destroyed by succumbing to his worst instincts, but again, so abruptly done it’s just jarring and unconvincing. From fighting for humanity and then cheerfully beering it up with comrades post-Long Night battle to bailing the next day and finally stating he doesn’t give a damn about anyone but himself and Cersei in the space of one episode – this from the man who at his prideful, obnoxious Lannister peak killed a king to save the small folk. They not only abruptly terminate and retard seven years of character development, they make Jamie a smaller and meaner man than he started. One has to ask, why? Has a certain nihilism set in and they simply wish to deliver a fuck-you to those good old audience expectations yet again, or did they just not think it through? I can only think that if this is how Jamie Lannister ends in the book series, going down in a pile of rubble with his sister, it will make a whole lot more sense than, ‘Got up this morning, decided I love Cersei after all, see you suckers in hell’.

I’d ask the same question about the whole kingship deal too. After a really jarring scene in which Grey Worm has inexplicably summons the lords and ladies of the seven kingdoms to decide the fate of Tyrion, and then allows the prisoner to dominate the proceedings, we end up with King Bran the Broken, for no reason other than Tyrion suggesting it for vaguely poetical reasons and everyone agreeing within a matter of seconds as if it’s a matter of deciding what to have for lunch. Bran, an impotent king with no heir or likelihood of it who is – quite literally – away with the fairies, creepily omniscient as his various quips imply, uninterested in the nitty gritty of ruling, doesn’t seem altogether like the wisest choice.

Amongst Bran’s closest advisors turns out to be Bronn, who may be a highly entertaining and understandably popular character, but is a man who has from the moment he appeared stated how his loyalty is always for sale. Then there’s Tyrion as his Hand, a man whose terrible advice, not to mention his eventual betrayal, set Daenerys up for eventual final defeat. Why is anyone listening to Tyrion at this point about anything, let alone Grey Worm? Why hasn’t Grey Worm killed Tyrion, and Jon for that matter, given his previous enthusiasm for murdering prisoners and traitors on the spot? Why didn’t Daenerys? She had nothing better to do than burn another traitor alive for the spectacle at that point but instead acted oddly reasonably toward him for a ‘mad’ queen and kept Tyrion on ice, unlike Varys. Perhaps, like Daenerys, Grey Worm recognised Tyrion and Jon’s incredibly thick and enduring plot armour and need to survive to the series end? This whole council scene has to be the most underwritten, illogical and unconvincing event to ever be portrayed in eight season with only Sansa really saying anything relevant to the realities of the situation.

We are then witness to a weird tonal shift with a meeting of King Bran’s Privy Council with Tyrion and Bronn sniggering about getting those brothels built again, eh? We’re left with two middle-aged frat boys who are concerned with having their boners serviced in the face of a ravaged continent with a pissed-off dragon on the loose, and Brienne of Tarth who is inexplicably writing soppy entries for the record about the precious honour of Jamie Lannister who, in Westeros term, had very much dishonoured her last time they met. Remember this is a world where a one night stand between Rob Stark and a girl from a noble house and issues of honour pertaining to that essentially led to the most infamous massacre of the whole series, the Red Wedding. Oh yeah, and there’s Sam to deliver a cringey reveal on the book series titles, and Sir Davos so we can hear one last Stannis-type grammar joke (Stannis told it better). In reality, how long is anyone expecting this dodgy set-up to last? And what is Bran really king of anyway, apart from a pile of bones, ash and rubble? Why does anyone need a high king now anyway, given he has no armies to protect them with or food to feed them with?

Is the subtext here that we’re just back where we started, the struggle for power is eternal and that all that bloodshed really achieved nothing? It’s really hard to tell if it’s all meant to mean anything at all. Perhaps like Jamie seducing Brienne before backflipping into sister-worship, it was all bit of ill-advised fan service because hey, people love Bronn’s wit and Brienne’s courage; Brienne is of course an underdog, and Sam has been set up as the greatest underdog of all time from season one so must predictably win everything – women, career, babies, life itself – whatever the obstacles or odds; and people understandably love the ever-sympathetic Peter Dinklage as Lannister underdog Tyrion -and want him to end well no matter how stupidly his character has behaved, and so on. It comes off as a weirdly shallow happy ending in a series which isn’t supposed to deal in them. Only Jon and Arya’s departures have any sense of bitterness or emotional devastation to them, although the nerd in me is still wondering where Arya found the money for the cool clothes, the sailors and the rather nice ship, given her ancestral house was just reduced to rubble and a whole lot of dismembered peasants. Endless war leaves you poor. Sansa got some nice new threads too, despite Winterfell being sat on and ripped apart by an ice-dragon and zombies not long before. Perhaps everyone individually made a run to the Iron Bank for a generous reconstruction loan? Remember when the series actually dealt with the reality of running a kingdom? So much is glossed over, which wouldn’t matter if so much of the series hadn’t been dead set on dealing with the actual intricacies of power before all this. You can’t help but wonder, as they all nod sagely at Tyrion’s whimsical suggestion that Bran should rule because he has the best story, what Tywin Lannister or Oleanna Tyrell would have to say about the whole thing.

There’s also the question of Bran’s or rather, the Three-Eyed Raven’s omniscience never being used when it would have advantaged the North and Daenerys, time and time again during the battle of The Long Night or beyond. Was that simply bad writing and we’re meant to believe just as Daenerys ‘kinda forgot’ (kudos Benioff and Weiss) the Iron Fleet existed in episode four, Bran ‘kinda forgot’ he could warg into animals, see all of the past and bits of the future and warp time (see the whole Hodor plot, seemingly long-forgotten) and so on because the writers sure did – or is there a suggestion he’s the real final villain of the piece, allowing the various bloodbaths to take place so that the One Eyed Raven, not Bran Stark, could eventually take the throne? A final defeat of men by the Children of the Forest? I honestly think that’s getting way too complex for what series eight turned out to be, which was really little more than a series of poorly-connected bullet points and some fan servicey bones thrown in here and there.

Of course, not all of the fanservice was terrible – it was great to see as much of the ever-popular Tormund Giantsbane as we did before he was consigned to the north again. Kudos to magnificent ginger Kristofer Hivju for his always pitch-perfect performance. The writers didn’t fail him either – he was as charmingly offputting as ever. There were some really nice small character moments in A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms too; Arya and Sandor’s brusque, understated conversation on the battlements, Brienne’s knighthood, Tormund’s flirting and Podrick’s song.

Great acting from Nikolai Coster-Waldau too, by the way, in his scenes with Tyrion and Cersei, and kudos as ever to Lena Headey who spent years perfecting that self-satisfied Cersei power-smirk and wine-swirl business. You can’t fault most of the acting in this series (OK, apart from that ridiculous moustache-twirling panto-pirate Euron Greyjoy hamming it up to eleven, but the blame for that lies directly with the directors), or the FX or the set piece battles; it’s just the narrative becomes hurried to the point of incoherence in the final stretch and the floor goes out from under the thing under the pressure to finish everything. Perhaps the lone survivor apart from Tormund in terms of character was the always wonderfully-written and played bitter bastard Sandor Clegane aka The Hound, whose character arc seemed fulfilled by trying to dissuade Arya from a life of soul-destroying violence (albeit a bit late in the game, and with far too instant success) and dying with massive courage, confronting his brutal brother and his lifelong terror of fire.

Overall though, I fall into the Daniel O’Connell , remote-chucking disappointment camp. I hope when The Winds of Winter finally emerges in print – in late 2020, we’re now told by Martin himself – I won’t be inspired to fling it off any form of public transport.

I first watched The Exorcist aged 14, a couple of years before it was withdrawn from UK home video circulation after being refused an 18 certificate under the 1984 Video Recordings Act. Its esteemed director, William Friedkin, has been forthright in claiming he intended the film to be an “emotional experience”. That concise précis perfectly describes my personal attachment to the picture, for numerous reasons. You see, up until viewing The Exorcist, my horror edification had largely been through gore-tinted glasses as I indulged in Video Nasty culture on VHS. But just a few minutes into Friedkin’s masterpiece, I was overcome with the sense I was watching a ‘serious horror film’.

I first watched The Exorcist aged 14, a couple of years before it was withdrawn from UK home video circulation after being refused an 18 certificate under the 1984 Video Recordings Act. Its esteemed director, William Friedkin, has been forthright in claiming he intended the film to be an “emotional experience”. That concise précis perfectly describes my personal attachment to the picture, for numerous reasons. You see, up until viewing The Exorcist, my horror edification had largely been through gore-tinted glasses as I indulged in Video Nasty culture on VHS. But just a few minutes into Friedkin’s masterpiece, I was overcome with the sense I was watching a ‘serious horror film’. Before long, the almost regal facade of the Georgetown University Campus stood proudly before me. Its Georgian brick architecture and proud steeple seemed to radiate a sense of history. Originally a Jesuit private university when founded in 1789, the structural design has remained intact despite the proud evolution of the buildings’ function. The campus site is of course briefly featured in the ‘movie within the movie’ sequence that serves to establish Chris MacNeil and Burke Denning’s characters and relationship. The liberal grassy zones in front of the eminent structure were now patently evident, as opposed to being crowded with the ‘demonstrating public’ in the movies preliminaries.

Before long, the almost regal facade of the Georgetown University Campus stood proudly before me. Its Georgian brick architecture and proud steeple seemed to radiate a sense of history. Originally a Jesuit private university when founded in 1789, the structural design has remained intact despite the proud evolution of the buildings’ function. The campus site is of course briefly featured in the ‘movie within the movie’ sequence that serves to establish Chris MacNeil and Burke Denning’s characters and relationship. The liberal grassy zones in front of the eminent structure were now patently evident, as opposed to being crowded with the ‘demonstrating public’ in the movies preliminaries. Despite the overtly sanctified status of the edifice, I was saturated with blasphemous cravings when I entered the vestibule. I couldn’t refrain from polluting the serene atmosphere with a puerile demonically whispered “it burns” as I placed my hand in the font of ‘holy water’, much to the embarrassment of my younger, yet considerably more mature cousin.

Despite the overtly sanctified status of the edifice, I was saturated with blasphemous cravings when I entered the vestibule. I couldn’t refrain from polluting the serene atmosphere with a puerile demonically whispered “it burns” as I placed my hand in the font of ‘holy water’, much to the embarrassment of my younger, yet considerably more mature cousin.  Obviously this is the property frequently referred to as the “Exorcist House” due to its portrayal as the MacNeil residence in the movie. The distinctive black metal railings that separated the property from the sidewalk have been predictably forfeited in favour of a solid wood privacy fence, no doubt due to pesky groupies such as myself.

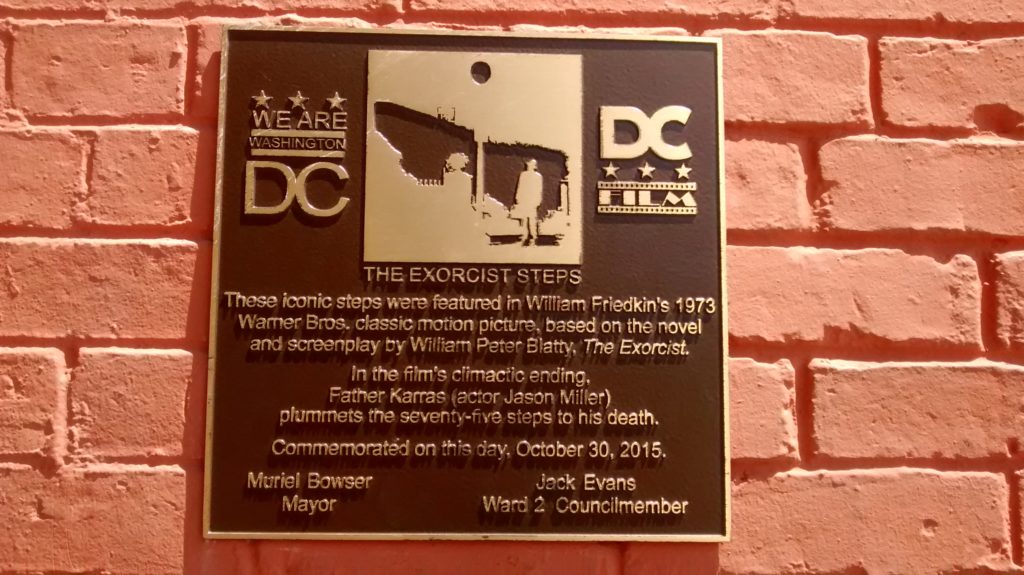

Obviously this is the property frequently referred to as the “Exorcist House” due to its portrayal as the MacNeil residence in the movie. The distinctive black metal railings that separated the property from the sidewalk have been predictably forfeited in favour of a solid wood privacy fence, no doubt due to pesky groupies such as myself.  The concrete staircase is offset from the house and it’s a renowned fact that an extension was temporarily built onto 3600 Prospect Street to give the impression that Regan’s bedroom indeed lingered above the 75 steps. Surveying the palpably steep descent from the landmark’s apex, I was instantly struck with just how impressive the stuntman’s plunge was, considering the precipitous concrete was only mitigated by a mere half inch of rubber at the time of filming.

The concrete staircase is offset from the house and it’s a renowned fact that an extension was temporarily built onto 3600 Prospect Street to give the impression that Regan’s bedroom indeed lingered above the 75 steps. Surveying the palpably steep descent from the landmark’s apex, I was instantly struck with just how impressive the stuntman’s plunge was, considering the precipitous concrete was only mitigated by a mere half inch of rubber at the time of filming.  Scrutinizing scenes in the film where the stairwell featured, I noticed the scarlet word “PIGS” apparently sprayed onto the wall just over the stairs railings. This had now been replaced by unreadable blue graffiti. The same ‘artist’ had seemingly added the obligatory “Fuck Trump” protest to the tourist attraction!

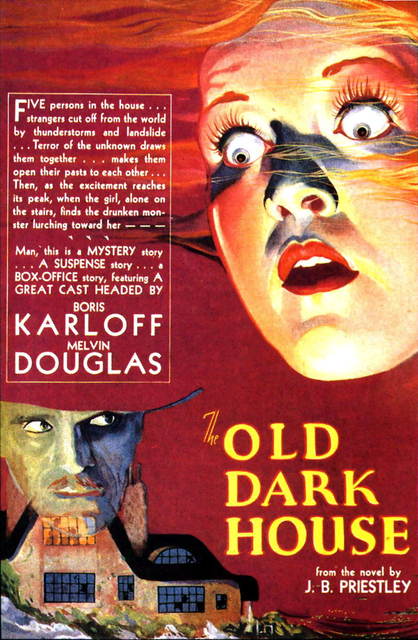

Scrutinizing scenes in the film where the stairwell featured, I noticed the scarlet word “PIGS” apparently sprayed onto the wall just over the stairs railings. This had now been replaced by unreadable blue graffiti. The same ‘artist’ had seemingly added the obligatory “Fuck Trump” protest to the tourist attraction!  Keri: When Universal Pictures set about cementing the developing horror genre with a series of tales – both old and embellished – the small country of Wales, in the United Kingdom, was oddly integral to this process. The ‘Old Dark House’ (1932) was set in deepest, darkest Wales, the rain lashing, forcing the house’s inmates to stay put until escape was possible; The Wolf Man (1941), which spawned a new horror archetype, silver bullets and all, saw its central character get ‘the bite’ in Wales, before running amok through its landscapes. Why was Wales, a country which has – let’s be fair – struggled to gain recognition as a country in its own right, chosen as the backdrop for these American productions? Was it just remote enough to serve a purpose?

Keri: When Universal Pictures set about cementing the developing horror genre with a series of tales – both old and embellished – the small country of Wales, in the United Kingdom, was oddly integral to this process. The ‘Old Dark House’ (1932) was set in deepest, darkest Wales, the rain lashing, forcing the house’s inmates to stay put until escape was possible; The Wolf Man (1941), which spawned a new horror archetype, silver bullets and all, saw its central character get ‘the bite’ in Wales, before running amok through its landscapes. Why was Wales, a country which has – let’s be fair – struggled to gain recognition as a country in its own right, chosen as the backdrop for these American productions? Was it just remote enough to serve a purpose? Wales also has a history of social protest and insurrection, which perhaps has some perhaps troubling pagan overtones – maybe prompting the question – how well does one know one’s neighbours? Welsh protest moments are, by any accounts, a strange phenomenon. The ‘Scotch Cattle’ of the early 1800s blended theatricality with real menace. Consisting of groups of men unhappy with their treatment at the hands of bosses or colleagues, they would gather at night for what were called ‘midnight terrors’, often wearing animal skins, blackened faces, with some blowing horns and many bellowing like cattle. This was intended to intimidate, and no doubt, it worked. The Cattle would damage property and machinery if they felt it was necessary to their aims, and they sent dramatic warnings to their peers – often written in animal’s blood. A message left as a warning to blacklegs (strike-breakers) stated, after naming the men responsible, “we are determined to draw the hearts out of all the men above named, and fix two of the hearts upon the horns of the Bull…we know them all. So we testify with our blood.”

Wales also has a history of social protest and insurrection, which perhaps has some perhaps troubling pagan overtones – maybe prompting the question – how well does one know one’s neighbours? Welsh protest moments are, by any accounts, a strange phenomenon. The ‘Scotch Cattle’ of the early 1800s blended theatricality with real menace. Consisting of groups of men unhappy with their treatment at the hands of bosses or colleagues, they would gather at night for what were called ‘midnight terrors’, often wearing animal skins, blackened faces, with some blowing horns and many bellowing like cattle. This was intended to intimidate, and no doubt, it worked. The Cattle would damage property and machinery if they felt it was necessary to their aims, and they sent dramatic warnings to their peers – often written in animal’s blood. A message left as a warning to blacklegs (strike-breakers) stated, after naming the men responsible, “we are determined to draw the hearts out of all the men above named, and fix two of the hearts upon the horns of the Bull…we know them all. So we testify with our blood.” The so-called Rebecca’s Daughters also challenged the social order in a theatrical manner, this time wrecking and burning the tollgates designed to generate income on Welsh roads, at the expense of many of the poorest in society. Dressing as women, led by a ringleader – ‘Rebecca’ – these men turned their actions into something of a dramatic performance, complete with a script. Surely, on some level this kind of history fed into the film Darklands (1996), albeit the film chose to explore cult consciousness rather than straightforward protest. Even the name, ‘Darklands’, corresponds with the so-named ‘Black Domain’ in South Wales, where many of the protest movements mentioned above took place, and in this film the amassed strangers with their rituals seem to call to that strand of Welsh history.

The so-called Rebecca’s Daughters also challenged the social order in a theatrical manner, this time wrecking and burning the tollgates designed to generate income on Welsh roads, at the expense of many of the poorest in society. Dressing as women, led by a ringleader – ‘Rebecca’ – these men turned their actions into something of a dramatic performance, complete with a script. Surely, on some level this kind of history fed into the film Darklands (1996), albeit the film chose to explore cult consciousness rather than straightforward protest. Even the name, ‘Darklands’, corresponds with the so-named ‘Black Domain’ in South Wales, where many of the protest movements mentioned above took place, and in this film the amassed strangers with their rituals seem to call to that strand of Welsh history. Branwen might be primarily tragic romantic history, but there are some profoundly horrific elements to it that would make for riveting – and entertaining – viewing. Likewise, there is some phenomenal body horror in characters such as Blodeuwedd, a woman created from flowers, a character whose ultimate fate some may vaguely know via Alan Garner’s

Branwen might be primarily tragic romantic history, but there are some profoundly horrific elements to it that would make for riveting – and entertaining – viewing. Likewise, there is some phenomenal body horror in characters such as Blodeuwedd, a woman created from flowers, a character whose ultimate fate some may vaguely know via Alan Garner’s  Director Chris Crow has a track record for imbuing his filmmaking with a sense of history and his most recent feature, The Lighthouse, is a really magnificent example of what can be achieved with notions of folk. By no means a traditional folk horror film, The Lighthouse draws on a singular moment in Welsh history and enlivens it with a tremendous sense of time, place and identity. The two men, trapped in the lighthouse in question, could well represent a rather traditional idea of the Welsh psyche befitting its period setting – God-fearing and self-loathing. Another recent example is Yr Ymadawiad (The Passing), a Welsh-language film which very strongly draws on Welsh history and landscape in such a wonderful way that to say too much rather spoils the film.

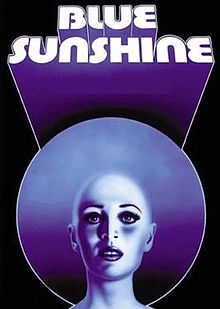

Director Chris Crow has a track record for imbuing his filmmaking with a sense of history and his most recent feature, The Lighthouse, is a really magnificent example of what can be achieved with notions of folk. By no means a traditional folk horror film, The Lighthouse draws on a singular moment in Welsh history and enlivens it with a tremendous sense of time, place and identity. The two men, trapped in the lighthouse in question, could well represent a rather traditional idea of the Welsh psyche befitting its period setting – God-fearing and self-loathing. Another recent example is Yr Ymadawiad (The Passing), a Welsh-language film which very strongly draws on Welsh history and landscape in such a wonderful way that to say too much rather spoils the film. ‘A passionate tribute to the cinema of Fulci’? It’s words like these which act like bait to writers like us, so when this statement was attached to the press release of a new film, Sexual Labyrinth, my curiosity was piqued. That the press release also mentioned paying homage to Joe D’Amato (ah yes, he) and Luigi Atomico (no idea) only made me wonder more what the film could possibly have in store. Well, spoiler alert: this ‘vision of female sexuality’, again words used in the press release, has nothing whatsoever to do with Fulci that I can see, from his early sex comedies all the way through to his horrors. Nada. Joe D’Amato? Not an expert on his stuff, though I’ve seen a few D’Amato films, and I suppose the rough-shod human flesh on display throughout wouldn’t have looked too amiss in some of his work – though I’m not sure that this is particularly ambitious on the current filmmaker’s part, or complimentary on mine. I think the best thing to do here is to say a bit more about what is on offer.

‘A passionate tribute to the cinema of Fulci’? It’s words like these which act like bait to writers like us, so when this statement was attached to the press release of a new film, Sexual Labyrinth, my curiosity was piqued. That the press release also mentioned paying homage to Joe D’Amato (ah yes, he) and Luigi Atomico (no idea) only made me wonder more what the film could possibly have in store. Well, spoiler alert: this ‘vision of female sexuality’, again words used in the press release, has nothing whatsoever to do with Fulci that I can see, from his early sex comedies all the way through to his horrors. Nada. Joe D’Amato? Not an expert on his stuff, though I’ve seen a few D’Amato films, and I suppose the rough-shod human flesh on display throughout wouldn’t have looked too amiss in some of his work – though I’m not sure that this is particularly ambitious on the current filmmaker’s part, or complimentary on mine. I think the best thing to do here is to say a bit more about what is on offer. By Marc Lissenburg

By Marc Lissenburg By Keri O’Shea & Nia Edwards-Behi

By Keri O’Shea & Nia Edwards-Behi

By Ben Bussey

By Ben Bussey