The Indonesian genre cinema which I know best is decades old now, but it certainly tends toward the unforgettable; during the country’s 1980s cinema boom, its genre film was clearly in love with the opportunities afforded by SFX (however rudimentary), leading to some incredibly lurid, overblown pieces of work, heavy with folkloric influences. In some ways, the reimagined Queen of Black Magic is a continuation of that early work, not least through its new spin on the classic 1981 title – even if its plot deviates quite a long way from the original and even if the newer film is mostly a wholly more slick, polished affair – more New French Extremity than old-school Indonesian. That being said, as the newer film ratchets up the action, it definitely shakes hands with its predecessor in a few places. It’s a visually-strong, very modern looking film which builds on familiar horror story elements to unleash something both grotesque and – on several levels – disturbing.

I said the film makes use of familiar horror elements: there are no surprises, then, when we begin with a car trip to a place which apparently doesn’t feature in any maps, or have any phone signal. The reason for this family outing is that Hanif (Ario Bayu) wishes to revisit the orphanage where he was raised. The man who was instrumental in his upbringing, one Mr Bandi (Yayu A.W. Unru) is ill and likely close to death. This trip also brings up the fact that not everyone has a regular family upbringing, something which Hanif wants to bring out into the open with his wife Nadya (Hannah Al Rashid) and their kids. This is a plausible family group, by the by, and kudos to all concerned parties that the kids themselves aren’t immediately unlikeable offspring. It really helps. Moving on, after that somewhat tropey journey to their destination, the family arrives: Hanif is meeting up with some other old friends from their orphanage days, themselves accompanied by their wives. Also present is Maman (Ade Firman Hakim) and his wife Siti (Sheila Dara Aisha), who made the decision to stay on at the orphanage as workers.

They all visit Mr. Bandi; it seems to be an affectionate reunion at first, but the old man soon afterwards seems to grow distressed – ostensibly at the appearance of Nadya, though it’s not clear. He’s non-verbal, and unable to explain his fears. The ex-inmates of this place are a little perturbed by now, and it isn’t too long before reminders of a troubling episode in their childhoods makes its way into conversation, albeit via one of the teenage resident’s scary stories. But in this house, scary stories have a backbone of fact. Tensions, incrementally at first, begin to rise. Hanif begins to wonder if the event which waylaid his household on the way to the orphanage was all that it seems, and wants to go back, take another look. Bad idea. As the past of this place erupts into the present, every clue makes these returners confront it, before it finally confronts them. People isolating themselves from the group is one of the first things which bring the real horrors onward.

And yet, the first thirty minutes or so of this film are very low-key, give or take. The Queen of Black Magic sidesteps the tendency to make the location creepy in a formulaic way; the orphanage is a little threadbare, but not dismal; likewise, the small number of older children still living there are not deliberately scary Others, but just kids contending with the double whammy of poverty and being orphaned, or abandoned. The visiting adults are initially pleased to be back too, even if it’s a little bittersweet. But this steady development of ease and calm is all the readier to be suddenly hacked away; if the film feels somehow like it’s on the verge of breaking out, then – oh, boy. The shift from uneasy restraint to overblown macabre is handled very nicely. Any divisions between magic, ghosts, curses and demons feels very arbitrary here; likewise, the term ‘black magic’ covers a seemingly very different range of phenomena than a Western audience might expect…

On its own terms as a horror film, The Queen of Black Magic works perfectly well but – in one of its significant shifts away from the 1981 version, it chooses to explore a few ideas which add subtext (rather than starting with a subtext and then adding a film, which is emphatically not the best way to tell a story). Wealth, class and the effects of modernisation are all touched upon here; a potential shift in the orphanage’s use is highlighted, bringing concerns about gentrification and its impact on the most impoverished, whilst we see a conversation between one child who doesn’t know what a VCR is and a girl who has never heard of streaming. More poignantly, the film deals with the subject of being orphaned and the vulnerability of children with no family, with a few conversations quite subtly introducing this; this in itself links specifically to the treatment of girls and women, be they utterly expendable, exploited, ignored – or seeking agency. It’s never a sermon; it does, however, weave through the horror itself and makes some unpalatable links to a world beyond the fantasy, even if the fantasy definitely takes over towards the film’s conclusion.

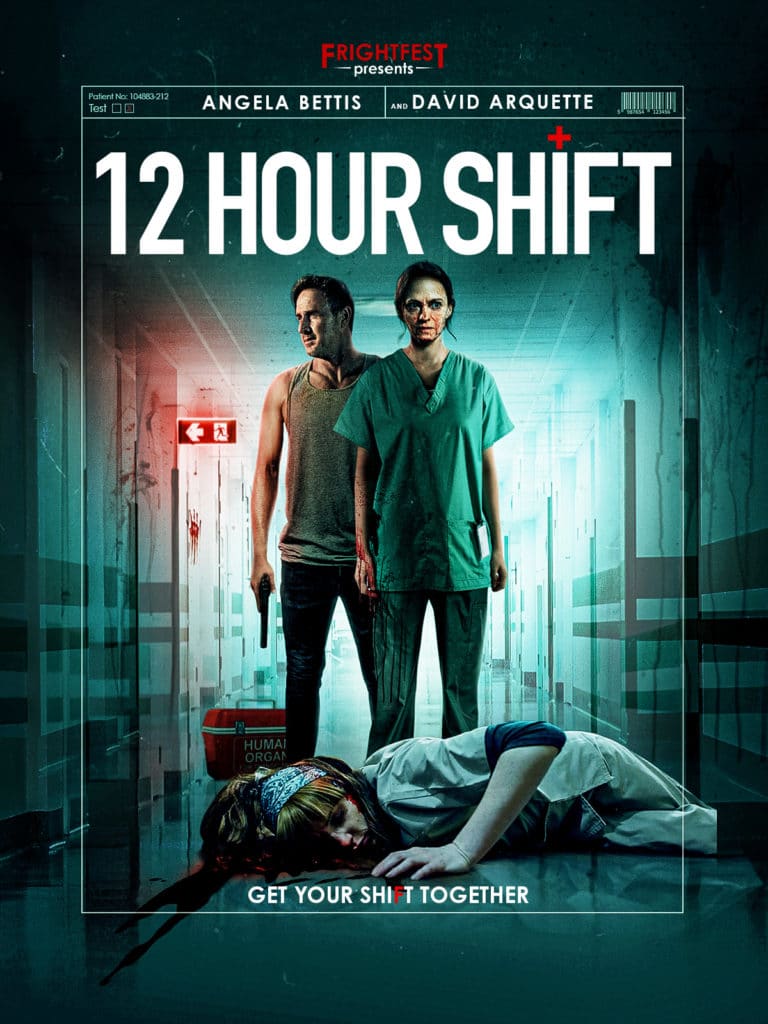

The Queen of Black Magic looks very recognisable in its earlier scenes, and it clearly has an awareness of Western horror which it adds to its Indonesian elements. (You’ll recognise some Eastern tropes, too, to be fair). You may, in the early parts of the film, have a few guesses as to where it’s all going, and you may be right. However, as it moves on, the film moves much closer to the action-heavy, even grandiose style which its Indonesian genre film predecessors typically went for. It manages a fairly effective twist, too, without sacrificing the direction it’s heading in or its grisly set pieces. All in all, this is an effective blend of styles and supernatural beliefs which makes for an entertaining, ‘familiar-different’ horror. Director Kimo Stamboel keeps things visually pleasing (if unpleasant) throughout.

The Queen of Black Magic comes exclusively to Shudder on 28th January 2021.