Elvira (Lea Myren) is a young girl in love with the idea of being in love. More specifically, she’s in love with the idea of one Prince Julian, an eligible royal who just so happens to be a published poet: she pores over his verse incessantly. Briefly back in the real world, she, her younger sister Alma and her mother Rebekka are about to move in with her mother’s new husband-to-be in a very fine ancestral pile in Swedlandia – but it’s not a complete deviation from Elvira’s fantasy, as you can see Prince Julian’s castle from the window. On a tour of the new digs with her new stepsister Agnes (Thea Sofie Loch Næss), Elvira expresses her desire to marry the prince, looking longingly across the valley to where he lives.

Such an aim becomes something more akin to a duty, however, when her new stepdad dies nearly instantaneously, and like all good aristocrats, it seems he was actually penniless. He has that in common with his new wife and her daughters, who perhaps misrepresented their own wealth just a tad. Someone has to marry well, and quickly.

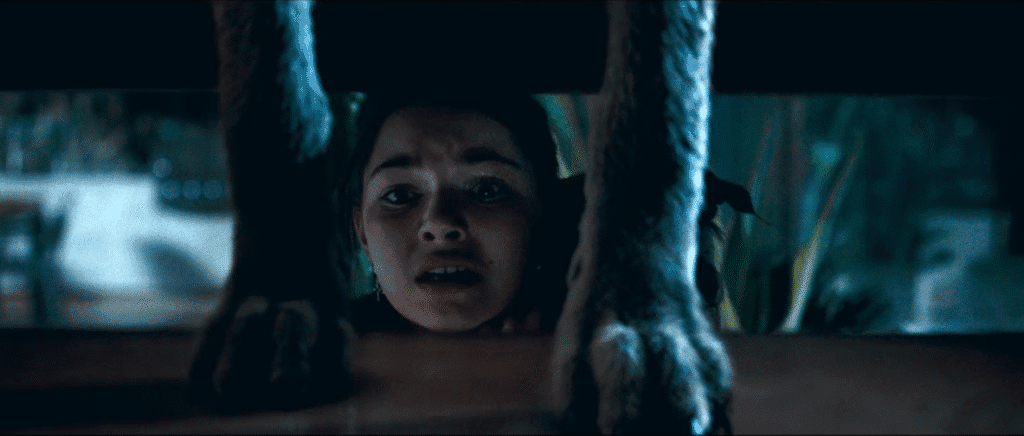

There’s a snag. Elvira is too plain to be a catch. Poor kid; she’s actually very pretty, rudimentary braces and all, but she has more of a doll face than the noble mien of, say, her stepsister, who fits in far more with the ideal: she’s tall, slim, blonde and dignified. When Prince Julian announces that he will be holding a prestigious ball in a month’s time, this only adds to the pressure for Elvira, both from herself and her mother: what’s a diligent parent to do, except dodge the funeral expenses for her newly-deceased husband in order to splurge on a few tweakments for her daughter, or in other words, her best hope for a luxurious retirement?

As the film progresses, we get a blend of 19th Century aesthetics and finishing school values with a 21st Century determination to embody them. Elvira and a whole host of other young hopefuls attend deportment lessons and a dance school; Elvira also undergoes separate ordeals, getting fake lashes (oh my god) and even a nose job, all blurring together as the only real course of action for a desperate, and genuinely lovesick teen. In all her hopeful, anxious glory, Elvira undergoes everything asked of her, even though she’s not a natural, and even though she’s soon shown that the ideal of the untouched bride and the loving, respectful partner are equally contrived. The film spares no blushes when it tackles the economy of women’s appearances; it spares no blushes when it deals with the sexuality at its core, either, with a few sex scenes which are genuinely, surprisingly graphic and about as far as it’s possible to get from the glib romantic verse Elvira likes so much. Given the period setting, the body horror which steadily increases as the film rolls on is set against what was a very real pressure on women to marry, and marry well. It was the only way to survive, let alone prosper in this era.

From the dark, panelled walls serving as a background for the hot pink opening titles, The Ugly Stepsister is all about the contrasts. This is a beautiful world of ringlets, cameos, satins and silks; it’s also riven with worms – there are lots of worms in this film, and in different forms – as well as blood, splattery gore and spoilage. As such, it’s made clear early – and often – that there’s a lot of darkness at the core of seemingly quaint fairytales, forcing us to notice (or to find out) that, when you look closely at some of the details which are glossed over so that the happily ever after can come to pass, traditional bedtime stories are potentially stacked with violence. There’s no sanitisation here, and director/writer Emilie Blichfeldt has a lot of grim fun with narrative gaps and overlooked character perspectives. It gets clearer what is going on here as the film progresses, but as we proceed, there’s a wide range of likeable characters to enjoy, even when they’re behaving deplorably. Agnes undergoes a horrible ordeal, as much as Elvira’s mania causes her serious harm and heartache, too. If the older women here are harsh and mercenary – which they really bloody are – then the point is still made that they’ve been ground down at the same mill as their daughters and pupils.

If, after an hour, you find yourself wondering where we can go next, then The Ugly Stepsister does not disappoint once we get to the batshit mad marketplace that is the ball itself. This event, and its fallout, leave us in no doubt of the film’s bigger message, even whilst drawing us on through it – a little reluctantly, perhaps, once all this bodily perfection starts to break down in graphic and often very audible ways too. This film feels like a Brothers Grimm (or Charles Perrault) mash-up with The Substance, this time for younger women, all reflected in the distorting mirror of a well-known fairy story – sometimes inventively, but sometimes very faithfully. The resulting film is a great success: this is a provocative, painterly body horror, shining new light on old ideas and ideals in engrossing and often darkly comic ways.

The Ugly Stepsister (2025) is available to watch on Shudder.