In a darkly comic film which seems to strive to fit in as much practical gore FX as possible, The Chamber of Terror suffers to an extent for its ambition, but on balance, achieves much of what it sets out to do. You can’t really criticise its enthusiasm, even if there are a few missteps along the way.

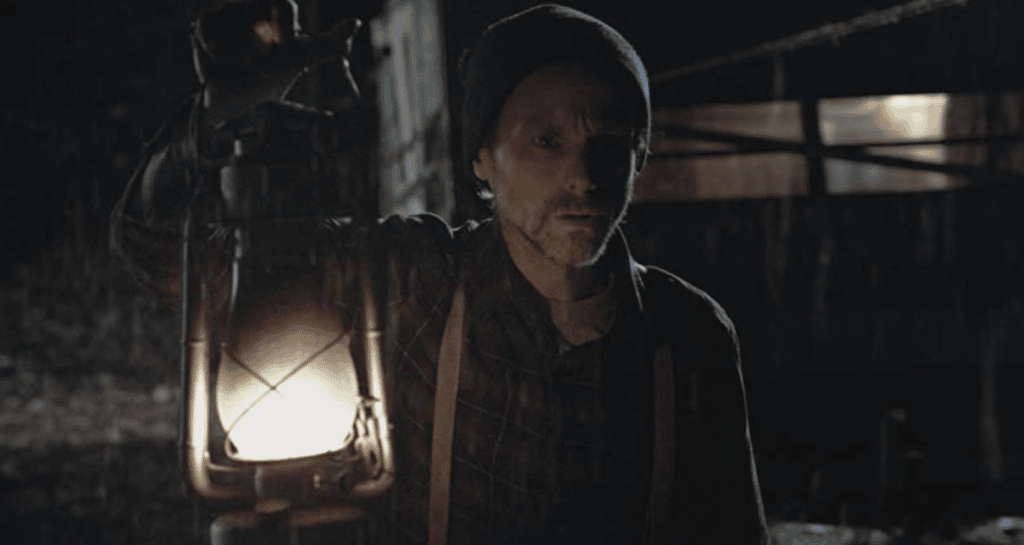

We start with what is clearly intended to be a franchise character – one Mr Nash Carruthers, who has a ‘shit list’: this means gathering up a number of people and putting them through some pretty unpleasant situations, and all in the name of personal vengeance. It wouldn’t be much of a shit list otherwise. We see some of this going on before the credits even roll; this is another love letter to 80s horror in many respects, right down to the title font, and certainly in Carruthers’ badass characterisation. And, it seems that Carruthers has the son of a local mobster in his sights. He tortures one Tyler Ackerman, hammering him into a box and leaving him there. We’re led to believe that Tyler’s a goner, and that’s that: we’re primed for Carruthers doing more of the same.

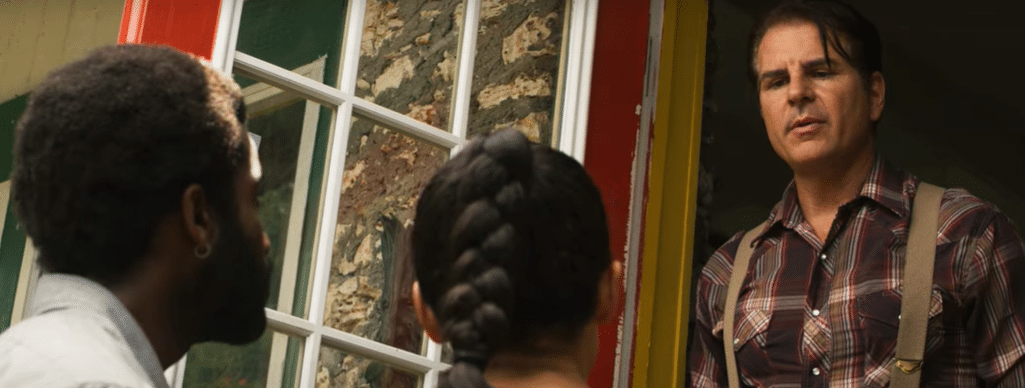

Instead, a month passes: Carruthers is still at large, but his down time gets disturbed by a couple of masked intruders. They’re not entirely pros, but they’re still able to capture Carruthers and take him to the Chamber of Horrors itself, a torture set-up in a safe house which is being overseen by Ava Ackerman, Tyler’s sister. The Chamber of Horrors has a long standing, and Ava is prepared to use it to find out where her brother is. Carruthers is taking it all rather well; it even seems like he’s enjoying himself.

As Ava strives to take control of the situation, things take an…unexpected turn. Not only does Ava get the information she wanted about her brother, but there’s more taking place, meaning that this is no longer a straightforward torture horror – which it could have been, all told. The film changes tack completely, transforming into a very gory homage to a hundred and one existing horrors, and perhaps one of its issues is that it does try to fit so much in, swinging the plot away from one thing to something else entirely. There’s clearly affection for the genre, though this does veer towards self indulgence in some places; there’s a lot of dialogue, but it takes some time for the characters to really ‘stick’, which holds the film back in the earlier acts to some extent. Some characters are there, loud, and then they’re gone, which can be a little jarring. But it knows what it’s doing in terms of how it paying lip service to horror, openly alluding to it in the script on more than one occasion. You may or may not enjoy this approach, but it’s loud and proud at least, and it does manage the about-face rather well, turning into a different genre of horror entirely.

Whilst the film could have used some cuts where it starts to dawdle – the hot-cold-hot game, for example – when it gets going, its change of direction makes it into a dead cert festival crowd pleaser, the sort of thing which elicits cheers from an audience. It spends a lot of time setting up what is essentially a gore fest, and perhaps sacrifices some plot to get there, but the SFX is very good fun, as well as nicely done on the film’s limited budget. There are viewers for whom this kind of back-to-basics gore is the most important element of their horror cinema, and it’s clearly close to the heart of director Michael Pereira, here directing his first feature-length film, but with a back catalogue of similarly OTT fare in his filmography. So yes, there are a few lulls and a few choices which could be questioned along the way, and its self-referential style may not be for everyone, but there’s plenty of ambition here, as well as – overall – enough going on to keep The Chamber of Terror entertaining.

The Chamber of Terror will screen as part of the Blood in the Snow Film Festival on 20th November 2021.