The Breach (2022) knows exactly what it wants to be: that is, a solid horror yarn, a midnight movie by design which might not surprise you with its plot elements, but will keep you consistently entertained as it burns through a significant number of genre features. Directed by Rodrigo Gudiño, founder of Rue Morgue magazine, and produced by Slash (who also worked on the film’s soundtrack) it certainly comes from an interesting and knowledgeable place; it’s also quite a different prospect from Gudiño’s very gloomy, more atmospheric films to date, although The Breach, too, does add in a few effectively ominous moments along the way.

When an abandoned boat picks its way down the Porcupine River and eventually gets stranded on a nearby shoreline, it’s found to contain a very badly disfigured body (which, by the way, ruins a picnic). At Lone Crow Police Station, the damage is deemed so extensive that they need to call in a coroner to examine the remains; in a way, they needn’t have troubled him, as how a body could end up in such a state stays a mystery. In the meantime, ID found with the body suggests it’s what’s left of a Dr Cole Parsons, physicist, who had rented out a remote farmhouse up at Lynx Creek. You know what he was doing up there without being told; he was doing some grand, secretive experiment which necessitated him shipping in a lot of scientific equipment. You also know that no one does science in a horror movie and actually turns out anything benevolent.

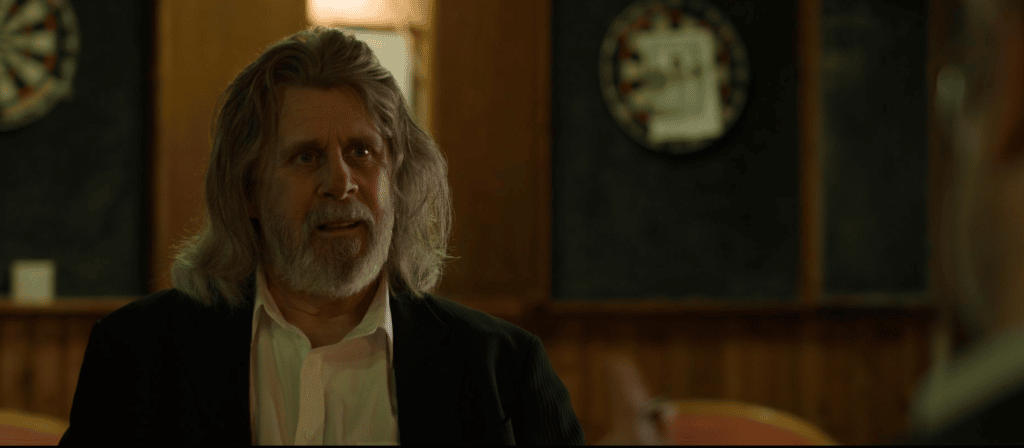

A team of specialists from Lone Crow go up to the house to investigate: this is soon-to-head-for-pastures-new police chief, John Hawkins (Allan Hawco), a ranger, Meg (Emily Alatalo) and the coroner, Jacob (Wesley French). There’s some bad blood between these three, stemming from a love triangle of sorts, which is plausible enough in such a small town. Thankfully, there’s not much time for this to become a problem. When they get to their destination, it seems dilapidated and deserted: it’s also as good a creepy abandoned house in the woods as you could hope for, and as luck wouldn’t have it, they all need to stay the night given how far from civilisation the house is. There’s some fun second-guess-yourself strangeness from the outset here; there’s also abundant evidence of Bad Science, with cables, monitors and a strange pod of some kind which could easily have turned up in The Fly (1986), whilst the walls are covered with scrawled occult symbols and foreboding artwork (demons; pained, spectral faces). This could quite easily and straightforwardly have turned into a game of Survive the Night, and the film no doubt would have done a good job of that, but it gets stranger still: other people begin to turn up at the remote house, including Dr Parsons’ estranged wife, looking for their missing daughter, and next – Parsons himself. So whose was the body in the boat?

Based on an Audible story by Nick Cutter (Craig Davidson), The Breach plays it fairly close to the book but takes up the challenge of illustrating the scenes which unfold, which to this reviewer gives the film a kind of graphic novel feel and look; most of the scenes would work as panels, and this kind of treatment also goes some way towards excusing some of the film’s minor issues: these being its performances, and its well-meaning, but sometimes harried determination to rattle through quite so many different kinds of horror genres and plot points, particularly in its third act. All of that being said, the homage feels affectionate throughout, and you can have fun picking up on some of the cosmic horror and body horror references which unfold. Lovecraft would of course be the immediate go-to, namely in The Beyond and to some extent, The Whisperer in Darkness, but also William Sloane’s In The Edge of Running Water with its own rendition of the road to hell being, at least at first, paved with good (scientifically sound) intentions.

To come back to the performances and the script, there are odd lulls and issues in these which are inescapable: the thought of there being some unresolved emotional relationships between the three key protagonists don’t quite come together, for example, though when the actors are given something more physical to do – as they soon are – things improve. In the script, too, there are moments where the fantastical developments don’t seem to generate the sheer concern which they might, but – again, given the fairly quick pace and rate of reveals – suspending disbelief doesn’t feel particularly difficult across the board. The film settles into a kind of campy, OTT and layered horror story, with increasing amounts of effective practical SFX. Whilst the resolution will delight fans of this kind of SFX perhaps more than people holding out for neat or novel plot denouement, overall the film’s busy energy and sense of its place in horror tradition will charm far more viewers than it will disappoint.

The Breach (2022) screened as part of the Fantasia International Film Festival and will also feature at FrightFest (UK) on Friday 26th August 2022.