Horror cinema writing is a broad and broadening church, despite (or perhaps because) of the increasingly ephemeral, online nature of much modern film criticism. Print media continues to be written, printed, read, collected and enjoyed, from the self-published to the most lavish tomes. It’s in a good place right now, and in The Vatican Versus Horror Movies, we have a deeply worthwhile project, as well as a knowledgeable and quietly passionate addition to the fold. It is focused squarely on a topic which has certainly served as context for other projects, but never as the topic in its own right.

After a personal introduction to his love of horror cinema, Rogerson organises his book into chapters which start with a linear look at the birth of popular cinema in Italy and the Vatican’s rapid self-positioning as arbiter of on-screen decency. This kind of value judgement wasn’t just taking place in Italy of course (and nor did the long arm of Catholicism stop at the borders) but the circumstances within Italy were unique. To understand what unfolded, it’s necessary to understand the Vatican’s chief means of disseminating its views on cinema, which came via print media, and a regular publication titled the Segnalazioni cinematografiche. Founded in the 1930s, it kept pace with the rapidly shifting and diversifying cinema of the day, with its own classification system on what was acceptable and what wasn’t, and – even during later decades of religious doubt and even apostasy in Italy – it retained significant influence.

Nonetheless, the Segnalazioni cinematografiche was, to an extent, blindsided by the sheer range and number of new releases which started to appear during the 50s and 60s, particularly the rise of horror – now, often homegrown horror. The author notes the vital importance of Italian filmmakers like Riccardo Freda and Mario Bava, and how their early work marked a shift away from merely ‘spooky’ cinema towards something much more challenging, provocative and Gothic. Bava wasn’t done here, either. Noting his influence on a range of genres and styles, the book moves onto different, specific horror and exploitation cinema subgenres, examining their emergence, notable titles (often influenced by films and filmmakers around the world) and of course, their reception by Segnalazioni cinematografiche critics. Included are: the early Gothic; the giallo; the slasher; the rape/revenge genre; the cannibal genre; the zombie genre; nunsploitation (well it’d be remiss to miss that one out); Nazisploitation and last – but not least – Satanic horror (ditto).

Whilst it would be intriguing to know more about the individual critics at work for the Segnalazioni cinematografiche (and indeed how they worked), it would likely be next to impossible at this stage, as well as going outside the remit of this particular text: what we do get is a wealth of primary source material, with ample coverage of the Vatican critics at work. This is often cross-compared with data on how individual film titles actually did (allowing you to decide how effective Vatican-approved moral warnings actually were) and also how successful or especially notorious films influenced other films – creating a thorough, engaging picture of the state of play of horror and exploitation cinema in the decades covered. In short, this is an exhaustively-researched book, but as it’s written by a diehard fan, it never feels like a purely academic exercise – as much as it is carefully referenced and studied. It retains an engaging flow and tone throughout.

For each of the films discussed, Rogerson takes a practical, measured approach, seeing as much in what the Vatican critics ignore (or even defend) as what they openly detest. For example, with regards to zombie horror, they reacted much more harshly to Ossorio’s fantastic Tombs of the Blind Dead (corrupted Knights Templar? No thank you!) than they ever did to Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (social commentary is admirable – when it’s happening ‘over there’). Some of their attitudes to rape/revenge films are positively mind-boggling, being far more put out by the sin of wrath (the revenge bit) than rape, which they often avoid discussing much at all. These are just a couple of examples, but they provide some idea of the fascinating intersection between religious belief and self-image propagated by Vatican film criticism. However, this isn’t a polemic: Rogerson often acknowledges the sympathetic receptions enjoyed by certain horror titles, and discusses these fairly. Granted, the Vatican is much more censorious of Italian films and filmmakers than they are of foreign ones, but nonetheless, there are plenty of examples of the Segnalazioni cinematografiche writers developing a style and voice of their own, as well as showing plenty of understanding of the filmmakers’ craft. Their reviews are not just one-note, and the book assesses them on a case-by-case basis, noting their more tolerant moments as well as their perhaps more usual, scandalised line. There’s plenty to be exasperated by, but there’s much more to it as well.

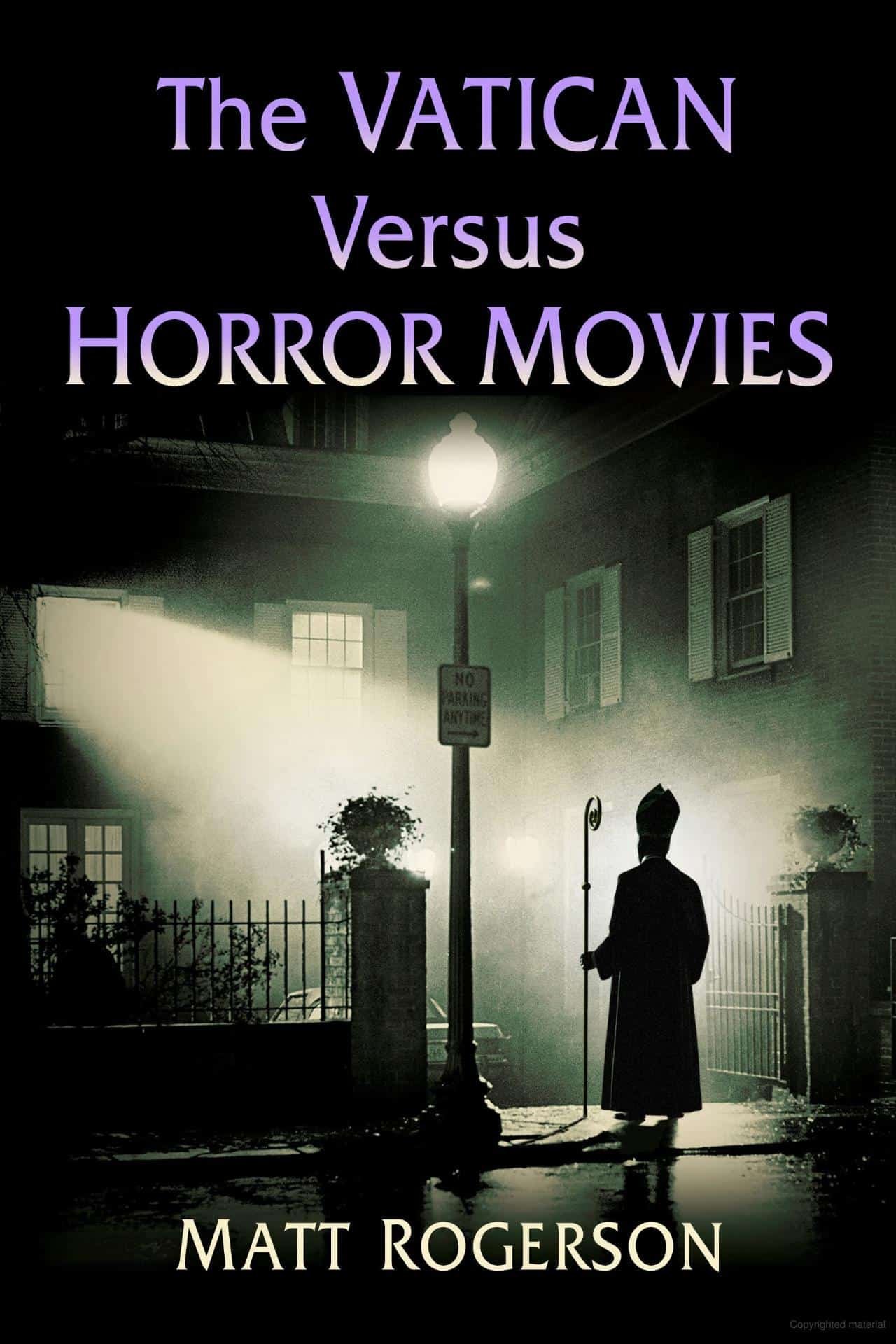

The Vatican Versus Horror Movies is a well-written, well-structured and very readable work, and the inclusion of black and white artwork by the author adds a nice personal touch. It’s clearly a labour of love, and whilst it could offer a great deal as a reference book, there’s really more of a sense of voice and enthusiasm here than you’d associate with just that. As such, it does just what it sets out to do, offering an engaging and ever-timely read on the relationship between cinema and religion.

You can grab your copy of The Vatican Versus Horror Movies here or straight from McFarland here.