Time flies, and it certainly doesn’t seem like three decades since I scored the poster for Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth from the local video shop, back when you could ask nicely for posters at the end of their release run and – if the member of staff took mercy on you – you could furnish yourself with a diverse array of wall art, to the detriment of the video store’s commercial waste (this was some time before widespread recycling). The poster was displayed proudly in my pre-teenage and teenage bedroom for years. Pinhead’s snarl sat tight through many of the milestones which followed – like exams. He even lasted as long as it took for me to move out – staying behind to snarl at nothing much, before finally being ousted years later.

The funny thing is that I liked the aesthetics of the poster just fine, but even to a kid, it was plain to see that Hellraiser III was a significant gear shift (and I didn’t get to see the film until some time after the poster was up, if it matters). It was and is an enjoyable enough film with some great scenes and interesting plot developments. It doesn’t feel, however, like one which has much in common with either of the Hellraiser films which preceded it, and as more and more time has elapsed – as more and more sequels of varying pedigree have emerged – it seems ever clearer that this was a parting of the ways. Rather than chancing a continuation of the dour, grimy, murky and very British nightmares of Hellraiser and Hellbound, Hellraiser III instead offered a slick, savvy, modern spin on the mythos, one which sits quite uncomfortably with its forebears; all of the subsequent films, each reaching for different arenas, themes and focuses, seem to have offered a series of diminishing returns. The Hellraiser rights now pass from hopeful team to hopeful team, each of whom has presumably had utterly earnest ambitions for this now classic array of cinematic monsters, but since Hellraiser III lifted the veil on the Cenobites for good, it’s never quite worked – certainly never as well, or in the same way, as it worked in the 80s. Perhaps audiences would inevitably have reconfigured their relationship with Pinhead and friends eventually, as familiarity always develops over time. That’s simply not something we can go much further with, though; we can’t say with certainty. As it stands, Hellraiser III was the film which brought us the sea shift.

The Pillar of Souls: Pinhead as Art(efact)

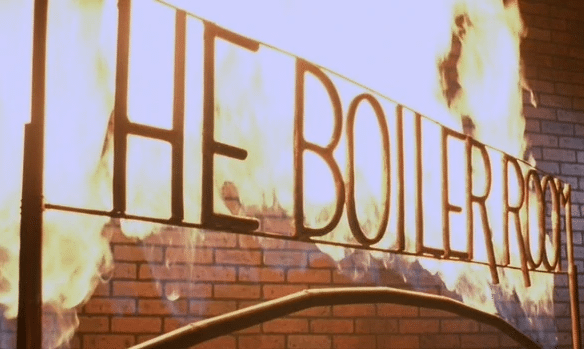

Things start interestingly enough, tantalising at some back story which becomes clearer as the film progresses but, at least based on what we see at first, Pinhead is front and centre here, something which remains the case. After the cataclysm which ends the Cenobites’ attempts to establish dominion in Hellbound, their de facto leader – running with the old idea that even demons have a hierarchy, and presumably middle managers – finds himself enmeshed and alone in what can best be described as a piece of modern art. There were previously some ideas to write a sequel where blueprints for the Lament Configuration puzzle box were used to map a proposed architectural structure, so links between the Hellraiser mythos and jinxed physical structures had been there in the background for some time; a similar idea would be used again in the following film, 1996’s Bloodline. In Hellraiser III, Pinhead – and the puzzle box itself – are now part of a sculpture, a pillar which seems to channel some of the body-and-blood obsessed outsider artists who were in the ascendant at the time – performance artists like Orlan, Ron Athey, artists and photographers like Stephen De Staebler, Andres Serrano and a Modern Primitives-inspired host of consumers who now saw bodies as canvases, art as having new possibilities to provoke. Against all of this, the somewhat-caricatured bad boy club owner, J. P. Monroe (a spirited performance by Kevin Bernhardt) decides to purchase the pillar, and at a steal: there’s possibly some buried subtext here about wealthy people who have no idea about art, in much the same way Patrick Bateman in the Bret Easton Ellis novel American Psycho hangs a David Onica painting upside down, to the great amusement of one of his victims. But the sculpture now belongs to Monroe: fitting right in with the aesthetics of his nightclub, The Boiler Room, it suits him down to the ground.

Monroe takes the sculpture home, and what’s notable here is that – through all the different forms he takes during Hellraiser III – Pinhead is actually on screen a great deal more than we’ve ever seen previously. The first two Hellraiser films are extraordinary in the way that the demons who preside over the deals humans strike with them, only occupy a couple of minutes of screen time. They are all the more menacing for that, too – lowering over what unfolds, supplying the rules and meting out the punishments: they don’t need to be there all the time. Their existence is equal to their presence. Come the event where Pinhead has got himself stuck in a pillar, separated from the other Cenobites, he can’t rely on people simply opening the puzzle box out of blind curiosity – at least, not yet. His ‘arena of influence’ is limited to a few feet around the pillar itself, making him temporarily a little more like a vampire than a soul-sapping demon, taking the chance to consume a girl who wanders too near, feeding on her to regain some of his former strength and presence. For anything further, he still needs some help. So he talks. And he talks, and he talks, and he talks. This isn’t necessarily a bad fit with the age-old idea that demons are good at tormenting humans via what they say to them; most exorcism horror films contain a sequence where a demon interrogates and/or humiliates the cleric at the bedside. It’s just strange to hear it from Pinhead here, who by the way really is a little wasted against poor old J.P., a man who doesn’t need much in the way of clever persuasion. Pinhead secures his assistance by making a few vague promises, and convincing J. P. that they are both hedonists, just of a slightly different kind. It works a treat.

This is the second encounter with the box and its tendency to fling chains into people, too: reporter Joey (Terry Farrell) is already hunting down a story after witnessing a Boiler Room clubgoer being yanked apart by these chains; she questions Terri, J. P.’s ex-girlfriend, who had accompanied the victim to the hospital. As Joey investigates, J. P. is getting drawn in to Pinhead’s bargain: bring me more girls, he says, and reap the rewards. Now reduced to something akin to Frank’s fate in Hellraiser – requiring flesh and blood to piece him back together again – Pinhead needs to feed, and his word seems good enough for J. P.

Once freed, Pinhead sees no reason to shut his yap, either, delivering line after line of dialogue about his favourite fleshly preoccupations, soon walking the streets of America with a whole new array of Cenobites (more anon). This gives us some fun scenes, if ‘fun’ isn’t an adjective you’d usually have placed too near to Pinhead in a sentence up until this point: the church scene, for example, where Pinhead flaunts his religious know-how by mocking both the Crucifixion and Communion, is very watchable – even if swapping quiet gloom for a massive stained glass window explosion. However, with hindsight, the overall impact of all this flimflam is to render Pinhead and his pals a little…overfamiliar. Once you film a conflab between timeless demons and modern cops, something of the mystery is inevitably removed – and removed for good. It’s impossible to put the genie back in the box once it’s out; Pinhead in particular becomes a household name and a very different character from this film onwards, but at the expense of his laconic best. It’s perhaps fitting that a character coming into the film as part of a hip art installation spends so much of the film in the company of equally up-to-date companions, wandering the streets and even rocking up in a nightclub. But then, this was always the plan. Hellraiser III was always about expanding the franchise, expanding the audience.

Pinhead for the Masses

After some uncertainty, Hellraiser III was directed by Anthony Hickox who, at that time, was fresh from the Waxwork movies, two films which had realised a modest profile and secured a place in the hearts of a fair few fans. A young director at the time, Hickox was tasked with what seemed to be the impossible: to make Hellraiser into a mainstream franchise, bringing Pinhead and the others more into line with sequel-friendly cinematic monsters like Freddy Kruger and Jason Voorhees, each at the time on six and eight films respectively. Although Hickox is British by birth, Hellraiser III has an American setting and a majority American cast (whilst the team which had worked on previous films was also different in some respects, though retained some continuity). As well as a new, American production company, it is interesting to note that Clive Barker was essentially paid off the project at first; then as now, it’s an incredibly strange (and some may say wrongheaded) thing to try and divorce a unique creative work so utterly from the person who created it. Eventually, the new rights owners came to agree, and then paid Barker another fee, this time to come back on board.

This lack of foresight arguably speaks to a misunderstanding of the subject matter. Another issue came with the insolvency of New World Entertainment at around this time; this created a lull and Peter Atkins’ screenplay sat on the shelf for a while before the project was up and running again. In the meantime, Barker’s attention was more fully on Candyman, a film which more successfully wedded the grimy, dour British style of Hellraiser horror – it was originally intended to be set in Liverpool, UK – with an American setting.

Lots of factors behind the scenes, then, had an impact on the filming of Hellraiser III, and it’s fair to say that the priorities of the production company led to some quite jarring changes to the subject matter along the way, too. Hellraiser III was shaping up to look and feel drastically different to the two preceding films, as an altogether glossier, louder affair, self-consciously tailored towards a young audience; even the poster was unusually colourful when held up against the cold blues and greys of the earlier promotional art. The very presence of a nightclub or a live band seems not to fit into the worlds of Hellraiser and Hellbound; you could easily believe that none of the main characters in those films (well, maybe except Frank) had even been near such a place in their lives. Hellraiser III doesn’t only show us a version of what was then an up-to-date, edgy-looking club, but also new themes: Joey Summerskill is a journalist struggling with the glass ceiling; Monroe is a representation of new, indolent money; poor old Terri is an itinerant hopeful looking to belong, and furthermore we pause to look at war trauma and psychology as well. There’s a lot more to get into here. Whilst Dr. Channard (Kevin Cranham) has a certain level of ambition in Hellbound, it’s not the plausible, relatable, wholesome ambition we see in Joey. The first two films feel much more localised somehow, and much more introspective, only offering up expansive places to explore only from within the box and its machinations. Hellraiser III definitely moves into the wider world, a world which suggests some interesting challenges and developments for the Cenobites. But it’s the new Cenobites themselves which speak most of all to this desire to modernise the franchise, broadening its appeal and speaking to the mainstream…

Hellraiser III: The New Breed

Whilst Pinhead has always been front and centre, the other Cenobites from the first two films are just as well known and beloved of fans, with their own nicknames and followings. And, perhaps part of their appeal was that nothing was really known about them. In the films, very little back story was hinted at – none at all was forthcoming in the first film – and certainly the Cenobites retained a sense of timelessness alongside Pinhead, having only the briefest of epilogues which hinted at anything more. They felt somehow like they could have been around forever, ambiguous figures who abide by certain rules in order to access their quarry for reasons we can’t quite grasp, and their lack of humanity helped emphasise the desperate situations of those who encountered them. Even Frank, himself transformed into an undead being, couldn’t escape his fate, even if he apparently took it all rather well at the end…

Well, even had the original Cenobites been a part of the new script, none of the actors had US work visas at the time Hellraiser III was about to film. And it seems that the production company had other ideas, anyway. Eschewing the rather more timeless Cenobites of the first two films – even if we accept the fact that they do seem to be wearing an extreme version of something you could have happily worn to Torture Garden at around the same time – Hellraiser III introduces several new Cenobites who, if we’re honest, seem to have been brought on board out of sheer necessity (Pinhead doesn’t seem to particularly enjoy being on his own, plus it looks like launching Hell on Earth can’t be done solo). Gone is the sense that the Cenobites have somehow ‘always been there’. Gone also is the feeling that, in order to be transformed into a being of this kind, some centuries-long process has to occur. After all, wasn’t it the Cenobites themselves who talk about things like eternity, heaven, hell, demons, angels? All of these things have a pretty long shelf life, and you’d maybe expect its operatives to have a similarly long pedigree.

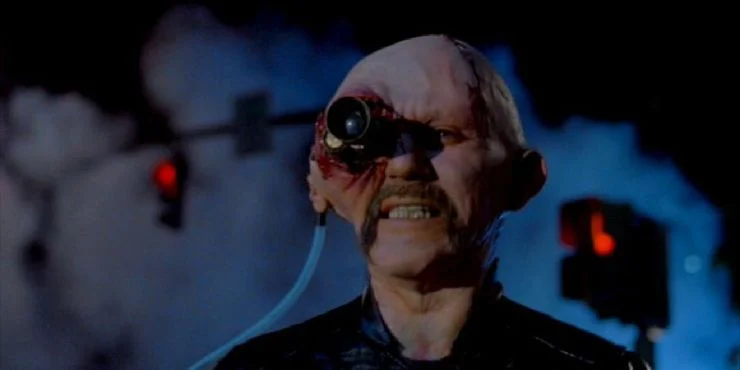

Instead, Hellraiser III makes Cenobites out of whoever happened to be standing in the wrong place at the wrong time; the recruitment process here is very much a fast-track one. Plucking a few of the film’s supporting characters from the streets, Pinhead transmogrifies a bar manager (Atkins), Joey’s media team, J.P. himself and Terri, who is sick enough of sofa-surfing to be talked into getting scalped and modified – an extreme reaction, by anyone’s standards. She also has the ignominious reputation of being history’s softest Cenobite: handed the ability to torment Joey into an exalted state of being, she opts instead to burn her a few times with a cigarette, a heinous torture indeed – which usually happened several times per night before the smoking ban. The rest of the new Cenobites are melded with the technology or other props which mattered to them in life and to be fair, there’s some potential here: it reminds me of Alien³, and how the xenomorph takes on some of the physical attributes of the dog it uses as a host.

The issue is that we always tend to imagine that whatever technology is current in a given moment will be cutting edge for a hell of a lot longer than it ever turns out to be. Equipping these Cenobites with video camera or compact disc add-ons damns them to something far worse than hell – it curses them to look a little daft after relatively few years have elapsed. Sure, they’re part of an interesting time capsule, and as certainly as filmmakers now electively fill their shots with tape players and analogue TVs, in a couple of years we’ll be watching films which ironically fixate on Discmans and first-generation Playstations. It’s going to happen. It’s inevitable. But can Cenobites go on through history terrorising the curious, when they look like they belong to a very narrow window of time? That seems more doubtful. This was, in any case, a decision taken to make the film appeal to its greatly-desired younger, hipper audience, people who bought into this kind of tech at the time. It was reasonably successful, if we go by initial reviews and box office takings; the new breed are also reasonably entertaining and the physical SFX are good (another ultra-modern calling card is the use of some digital effects, which have aged every day as hard as Mr CD has). The film also deserves some credit for getting creative in how the new crew dispatched their victims, even if we have to skip the logic that the Cenobites tended to torment those who tormented themselves, rather than any old unfortunate. In hindsight, these characters remain divisive, too much of a break from the complex mythos for some, perfectly acceptable, grisly set-piece fodder for others. As an addendum, we can only hope that the Hellraiser ‘reimagining’ which is currently in production doesn’t elect to add current technology to its own monsters, else the Cenobites might end up appearing in dog face filters, and just think how all of that is going to look in a few years. Progress is never a straight road.

The Art of War and final thoughts…

Hellraiser III‘s most surprising, and genuinely ambitious new direction was to interrogate the mental impact of modern warfare, which it does by separating Pinhead from his human originator, a WWI soldier, Elliot Spencer (also Doug Bradley) whose mind broke under the strain of the atrocities he’d witnessed. This extends the brief clues which feature at the end of the previous film. Joey, who has some kinship with all of this because she dreams of her own father’s fate in Vietnam, forms a strange bond with the pre-Pinhead Elliot, who seems to want to protect her, and helps her to fight back against Pinhead, who essentially has to fight for his own existence as a separate entity. Again, whilst this plot point could be seen to dissipate the notion of Cenobite omnipotence (or as near as damnit), it is at least an interesting idea, which also provides the film with its heftiest share of substance. Without it, the film is little more than an array of nightclub scenes and a few bad murders which would have divided fans/detractors even more unevenly.

It is, at least, some evidence that writer Atkins had more in mind than the most basic crowd-pleasing scenes, and worked to add something more complex here. That being said, the notion of a squaddie getting his hands on the Lament Configuration box is a little thinly plotted and bizarre; it scatters in some more context for the box itself (the next film would layer this on altogether more thickly) but ultimately, and not dissimilarly to the Nightmare on Elm Street sequels which usually offer a similar amount of closure, whilst not entirely ruling out that there could be more to come, it brings us back to a familiar point. The box is dispatched into some wet cement this time, and order seems to be restored, but – knowing the tenacity of that thing, it’s not beyond belief that it could make its way back out somehow, is it? The other option, of course, is to simply ignore the ending of the last film and go again in a new location with a new cast; this would be the selected way forward as the franchise moved on down through the years, each time with a shrinking budget and diminished set of ideas. It’s a shame, although it’s equally important to note that none of this takes anything away from the strongest films in the now long list of Hellraiser movies which we have.

So how do we characterise Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth now, at a distance of three decades of new films, franchises and ideas, a wave of torture porn, a slew of found footage and a steadily-growing subgenre of technological horror? I suppose, if anything, it all feels a little innocent now – despite the gory tableaux and intentionally graphic scenes which punctuate the film throughout. Clearly aimed at a new audience, and intended to diversify a ‘cult’ mythos which in the eyes of some needed to move away from its cult status, it has a surprising amount of optimism mixed in with equal amounts of cynicism. Someone – perhaps a few people – on the production company team could certainly dream, and there was a hope of a new direction, with more films and a bigger budget should Hellraiser III suffice. Some of this was rewarded when Hellraiser: Bloodline was optioned, but the Hellraiser mythos has had a very troubled run since…the fourth film? Or the third film?

Essentially, this sudden trip through American streets established too great a distance between old and new for many fans, and for these people, Hellraiser III has never quite felt like part of Clive Barker’s vision. Never will. For others, the Cenobites and their world was easily able to withstand a new setting and a few modern touches, and these people appreciate the film for what it is: an altogether more showy affair, with different levels of explication than seen previously. And, at the end of it all, it’s nice to look back and remember how damn excited I was when someone rented the film for me, and I got to finally see how the poster matched up: whilst any film should be able to withstand a fair appraisal, we can tend to be more sceptical these days, something which is worth bearing in mind as we reassess older films. All in all, Hellraiser III may be schismatic, but at least we’re still discussing it, and it does still have its place in the history of what – as the production company rightly pointed out – is now a timeless movie mythos, however we might feel about this film, and whatever followed.