I’m very glad that filmmakers seem to be returning to aesthetically-pleasing supernatural tales these days, rather than endless found footage or excruciating ordeal horror. You could argue that there’s plenty of space for all the above, of course, and you needn’t stick with just one genre of horror (or any other genre for that matter) but isn’t it a privilege and a treat to see a film which takes some pride in its appearance and its atmosphere? Just recently, I was treated to a viewing of The Lodgers (2017), a beautiful, almost painterly film which carries echoes of The Fall of the House of Usher in its tale of malign destiny. This particular film came to mind a few times during The Isle (2017), another atmospheric period piece which toys with ideas of fate – though this time striking out with an adventurous re-interpretation of pre-existing myth and legend.

The year is 1846. After surviving a devastating shipwreck whilst en route to America, three men manage to make it to dry land – which turns out to be a remote Scottish island, where only a handful of people seem to live, eking out an existence. However, the first islander to greet them – a man named Fingal MacLeod (Dickon Tyrell) – seems genuinely interested in their welfare, offering them food and shelter whilst asking what exactly befell their vessel. The sailors find that difficult to explain: a sudden turn in the weather made it impossible for them to navigate, they recall, but beyond that, they aren’t sure. Fingal promises to help them get back to the mainland regardless, and suggests they stay at the local farmhouse in the meantime. Grateful for the surly assistance of the Innis household, Oliver (Alex Hassell), Cailean (Fisayo Akinade) and Jimmy (Graham Butler) can do little but wait it out.

The year is 1846. After surviving a devastating shipwreck whilst en route to America, three men manage to make it to dry land – which turns out to be a remote Scottish island, where only a handful of people seem to live, eking out an existence. However, the first islander to greet them – a man named Fingal MacLeod (Dickon Tyrell) – seems genuinely interested in their welfare, offering them food and shelter whilst asking what exactly befell their vessel. The sailors find that difficult to explain: a sudden turn in the weather made it impossible for them to navigate, they recall, but beyond that, they aren’t sure. Fingal promises to help them get back to the mainland regardless, and suggests they stay at the local farmhouse in the meantime. Grateful for the surly assistance of the Innis household, Oliver (Alex Hassell), Cailean (Fisayo Akinade) and Jimmy (Graham Butler) can do little but wait it out.

It transpires that a history of shipwrecks in the area has taken a hard toll on the islanders over the years, with many of their young men lost and the population of the island now sadly depleted. Yet, even allowing for all of this, some of the islanders seem to be acting strangely – particularly the island’s women, Korrigan MacLeod (Alix Wilton Regan) and Lanthe Innis (Tori Butler Hart), who veer from gentle and fearful to seemingly desperate to leave the island themselves. Curious, the three sailors begin to explore, asking questions and gleaning as much information as possible. Their main question is simply this: why do these remaining people choose to stay in this bleak isolation?

At this point in the narrative, The Isle could quite easily have lapsed into cliché. Either it could have become a straightforward horror of the closed community, where a group of people lie in wait for hapless outsiders, or it could have become a supernatural horror which sticks to the now-expected formula of jump-cuts and oh-so familiar set ups. Happily, neither of these things come to pass, providing evidence of confidence and creativity on the part of writers Matthew and Tori Butler Hart. One of the really effective things about this story is how it avoids the jump-scare almost completely. There are one or two quicker cuts here, but overall, this isn’t a film which plays out in that way. Rather, the film tends towards the slow, subtle, ‘did I really just see that?’ approach, which is to my mind, far more effective and suited to the slow unfolding of the tale which takes place. When you realise something or someone unexpected is stood quietly in frame, for instance, the resulting skin-crawl is wonderfully in keeping with the overall atmosphere and careful handling of this story-within-a-story – a story which I urge you to keep hidden from yourselves until you get the chance to see the film. It would be remiss of me to say too much here…

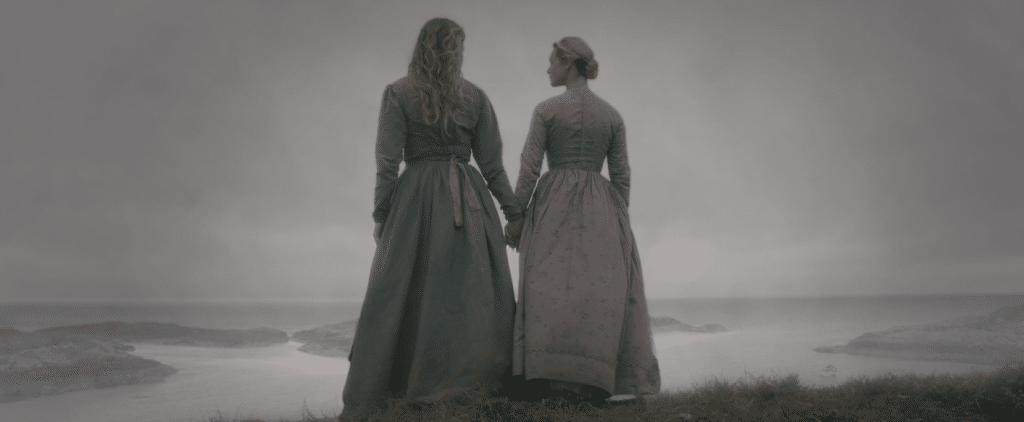

The film also takes its time in establishing characters, allowing them to build in an organic way without using line after line of exposition. Seeing the characters measured against the stark, but beautiful location seems to add a great deal to how we see them, too, and this requires almost no dialogue to be spoken at all. The unmistakeable Scottish landscape dwarfs the people on this island, both outsiders and residents, reminding the audience of how little agency they have in this unforgiving environment. More than this, the rocks, woods and beaches also figure hugely in the narrative: being lost, being trapped and being disorientated are states which propel the plot onwards in their own ways. And, before the film unfolds its surprises, finally revealing its secrets (The Isle’s changes in direction are genuinely surprising and engaging) we are kept on the same level as the characters themselves – never truly sure whether this bleak place can be taken on face value.

The film also takes its time in establishing characters, allowing them to build in an organic way without using line after line of exposition. Seeing the characters measured against the stark, but beautiful location seems to add a great deal to how we see them, too, and this requires almost no dialogue to be spoken at all. The unmistakeable Scottish landscape dwarfs the people on this island, both outsiders and residents, reminding the audience of how little agency they have in this unforgiving environment. More than this, the rocks, woods and beaches also figure hugely in the narrative: being lost, being trapped and being disorientated are states which propel the plot onwards in their own ways. And, before the film unfolds its surprises, finally revealing its secrets (The Isle’s changes in direction are genuinely surprising and engaging) we are kept on the same level as the characters themselves – never truly sure whether this bleak place can be taken on face value.

The Isle is a quiet, understated and almost austere supernatural tale – but it’s innovative, finely-drawn and confident, telling its story at the pace and in the way it chooses. Atmospheric and rewarding, it also leaves a judicious number of questions unanswered, but it’s the richer for this: the mystery is all part of the charm. I’m a little undecided on whether the text which appears over the opening credits should really be there, as it prepares you for certain plot elements which would otherwise take longer to come to light – however, how this element unfolds here is still a genuine surprise, and speaks overall to the quality of this project – this aspect of the subject matter is patiently developed and transformed, just like everything else here.

The Isle will feature at the East End Film Festival, showing on April 20th. It is not anticipated to be on general release until autumn of 2018. For further information on the festival, including ticketing, please click here.