A couple of years ago, my parents came to stay for a few days. One evening we had dinner, and I suggested we watch a film. After a bit of discussion, the choice was Robocop – the 1987 Director’s Cut. So we settled down to watch it. At the end, my father made this comment:

“Well. They certainly don’t make them like that anymore!”

To quote Clarence Boddicker – give the man a hand. He is absolutely correct. The combination of violent mayhem, religious allegory, social satire and dark humour, along with stop-start motion effects and a central performance that is essentially mime is not something I think will happen again in this era of glossy superhero fantasies. It was also released in 1987, the year of Superman IV: A Quest for Peace and Jaws: The Revenge – two films that were so laughably bad they killed their franchises and nearly tanked the summer blockbuster, full stop. It’s also quite amazing to think that a film which spawned two sequels, a cartoon series for kids, a TV series, and an unnecessary 2014 re-make (which not even the acting talent of Gary Oldman and shapely form of Joel Kinnaman could save) very nearly did not get made. Famed Dutch director Paul Verhoeven has admitted that when he was sent the script in 1986, he dismissed it as a silly little B-movie. (From the man who made Showgirls? Yes. Quite. ) It was his wife who picked it up, read it, and encouraged him to film it. But I will always forgive Verhoeven Showgirls for the fact he did direct it, and it is steady, uncynical eye which arguably makes it so good. Its a film about 1980s America, that could only come from a non-American. In an interview on his approach to Robocop, Verhoeven later stated “I do not condemn America. I do not celebrate it. I merely present it.”

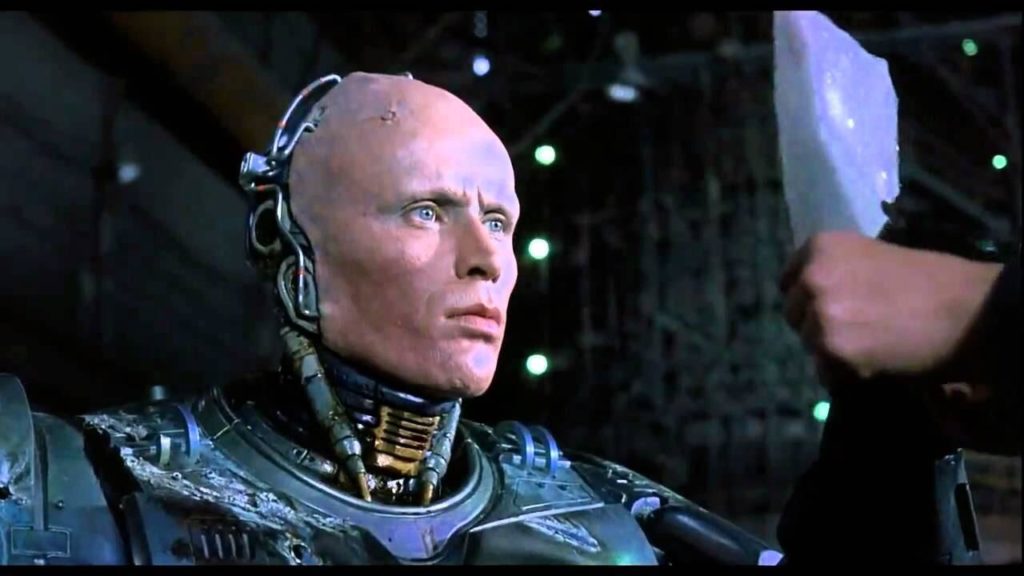

Robocop is indeed a statement on America – one that inverts Oscar Wilde’s famous quote that life imitates art. This is a case of art imitating life – and that life is the Regan-era. The 1980s, that decade of decadence, with money-grubbing corporations and cocaine-snorting yuppies having to uncomfortably co-exist with spiralling rates of crime and poverty. The war that seethes between these two sides is distilled down to the fate of one of the cops: Alex Murphy, in a career-defining turn from Peter Weller. A gentle-mannered, polite, good looking family man, Murphy is a beat cop assigned to the violent and near-lawless Metro Precinct. After being given short shrift by Robert DoQui’s world-weary Sergeant Reed (“We work for a living here, Murphy”) and introduced to his tough, loyal partner Anne Lewis, the audience is settling in for what appears to be a standard action film. Except this is a world where the cops are a commodity. And an audacious twist is taken when Murphy is gunned down after a mere 25 minutes.

Murphy’s death at the hands of Kurtwood Smith’s Clarence Boddicker, arguably one of the greatest villains in film, is one of the most violent and shocking on celluloid. Boddicker is a psychopath in lumberjack shirts with the demeanour of a Wal-Mart store manager who sits and calmly smokes a cigarette whilst his gang taunt and then shoot the vulnerable Murphy, and casually chews gum whilst putting a live grenade in someone’s house. Verhoeven has stated that Murphy’s death – which starts with his hand being blown off and ends with his body being virtually destroyed – had to be exceptionally violent. Because it’s a modern-day crucifixion. In Verhoeven’s words, “it is Satan killing Jesus”. The religious allegory is underscored with an eerie arial shot of a distraught Lewis seemingly praying over Murphy’s body. What was looking like a violent action flick is suddenly humanised. Horror gives way to grief. There’s a sense of shock and outrage amongst the audience – a man who was simply going to work ends up getting killed, and now there’s a desire to see Murphy return and take revenge on those who did this to him. At the end, he is practically walking on water towards Boddicker in the abandoned steel mill where he met his original fate, stating he is not going to arrest him. He will kill him instead. If Robocop is an “American Jesus”, he is one who does not see himself as a saviour of all.

But the violence of this film is not confined to the criminal street gangs. The glossy boardrooms of OCP are awash with blood as well – both literally and metaphorically. Reflecting an era when businessmen spoke of “hostile takeovers” and making a killing, Robocop ramps it up until they are actually killing each other to get ahead, a powerful comment on the corporate greed of the 80s. The most darkly comical moment of this is when Dick Jones (Ronny Cox), a designer-suited shark of a man, introduces ED-209 – a big, powerful robotic law enforcement machine – to an obsequious pack of executives. Except – it doesn’t work. When it malfunctions and sprays the gathering with yuppie gore, the battle is set between Jones and self-interested young upstart Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer). But there’s an extremely dark underside – OCP doesn’t care that a young man is lying dead in the boardroom, they’re just irritated that their multi-million dollar investment failed to come to fruition. And Jones is even more annoyed when Morton’s Robocop suddenly starts cleaning up Old Detroit due to his programmed prime directives, defending elderly couples, women, and becoming a hero for children. A wicked duel of wits begins, ending with a planned cocaine-fuelled threesome ending in carnage. It’s all about money and power, and who has the most of it. Relevant to Reagan – or is it also Trump?

But just as the film threatens to tip into mayhem, it reveals a battle for Murphy’s identity, and who owns it. Murphy is a quintessentially human protagonist. He’s not a machine that was once a man – he’s a man who is inside a machine. As Robocop starts to remember his all-human past, and starts to act outside the parameters set by OCP programming, his former partner, Anne Lewis, and the rest of Detroit police become sucked in. It’s a question of loyalty – can someone be owned? It’s also a point where the film shows echoes of that great horror literary classic – Frankenstein. The created turns on the creator, and reveals who is the real monster. The film builds to a crescendo with a very traditional outcome – the good guys win. But this is subverted by the violent mayhem that leads to that final scene. Good triumphs over Evil, but there is always a price.

And price is a strong element. Ownership looms large in this film. In a projected dystopia where human hearts are made by electronic companies and available for those who can pay for them, and board games depicting nuclear war are sold to families, Robocop depicts consumerism taken to its logical conclusion – companies own people, they own law enforcement. And as Dick Jones cheerfully informs Boddicker, OCP are practically the military. Think back to the sinister-looking black-clad figures standing outside the White House in 2020 – Jones’ vision of a militarised police does not seem like a fantasy. But the vision it portrays of a media where everything is reduced to a two-second soundbite presented by grinning loons that barely scratch the surface of an important event is spot on with our own. News is now just a string of Twitter notifications and shrieking headlines, all of which only serve to rile people up. Intercut with the mindless news flashes are even more mindless game shows – reality TV, anyone?

There is one element to this film that also makes it more than just another action film– the role of women. Nancy Allen’s Anne Lewis is tough, loyal, funny, prepared to put herself in dangerous situations, and knows how to handle a gun. She just happens to be a woman, joining those other sci-fi icons of the 1980s, Aliens‘ Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley and Terminator’s Linda Hamilton as Sarah Connor. It’s also worth noting that the cyberneticist responsible for creating Robocop is Dr Tyler – played by French actress Sage Parker, who casually dismisses Morton’s clumsy overtures towards her. Contrast this with the 2014 re-make, when women are reduced to being slimy CEO Michael Keaton’s assistant (a waste of Jennifer Ehle), or a standard blub role for Abbie Cornish as Murphy’s wife. Even the female scientists in the Robocop sequels got better treatment – at least Belinda Bauer’s villainous Julia Faxx was allowed to pretend to be clever.

Religion, feminism, a mediation on humanity, social satire, and a lot of blowing stuff up. Robocop can never be dismissed as just another action flick. And it’s safe to say that cinema would be a lot poorer if it could.

References:

Flesh and Steel: The Making of Robocop documentary

Paul Verhoeven Calls Robocop an American Jesus by Mark Rosenberg.