Whilst the genre of ‘found footage’ is more on a downward arc these days than it was, say, fifteen or twenty years ago – when every no-budget filmmaker was irresistibly drawn to its cheap, practical possibilities – it’s nonetheless so familiar by now that we can instantly recognise its trappings and conventions. As such, we only have to look at Nicholas Pineda’s debut feature to know that he knows them as well; before the cameras roll, he offers us a framing narrative in which some on-screen text reveals that, in March 2023, authorities responded to an ‘unknown disturbance call’ at the Wilshire Infirmary, where they located two deceased individuals. This being established, we’re told that the following film is assembled from recovered footage. And so we begin.

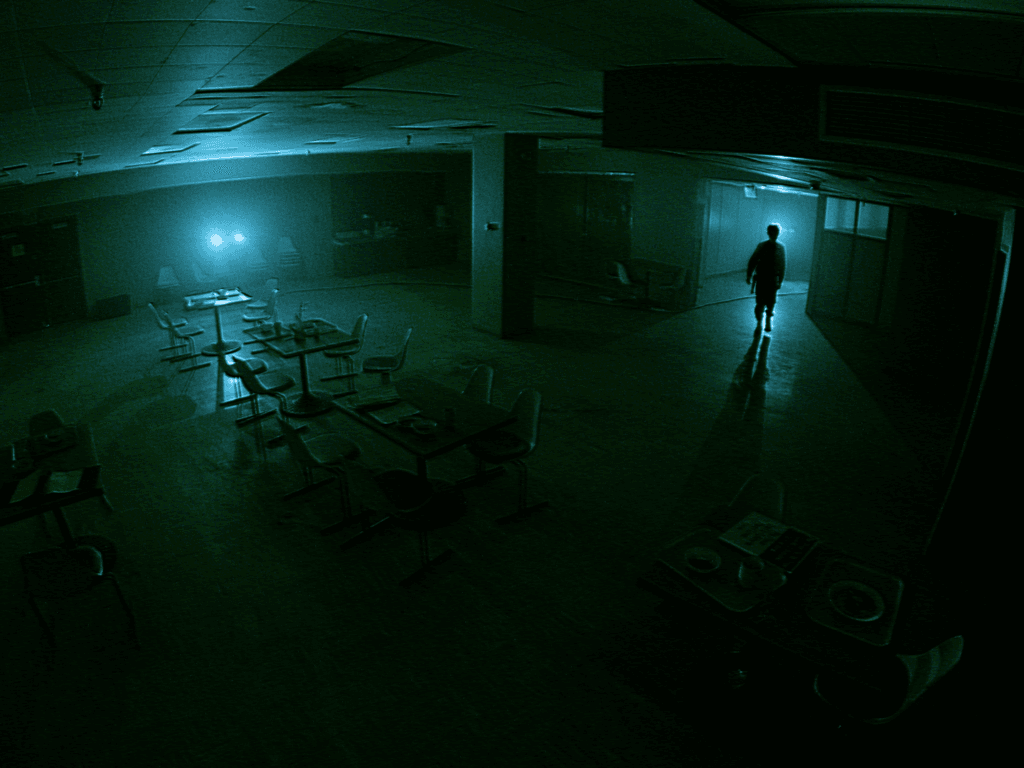

The Wilshire Infirmary is a deserted hospital; the film itself starts when we witness the arrival of a hospital security guard called Edward (Paul Syre) who, to judge by his tendency to get lost in the halls, is a rookie here. Indeed it’s his first shift, and he’s made none too welcome by old hand Lester (Mark Anthony Williams), who’d rather sleep in his office than get into the rigmarole of showing the new guy the ropes. The use of bodycams brings the film down to eye-level, contrasting with the surveillance cameras which are our first interface. This allows us, at least some of the time, to look our characters in the eye. We also learn that the building is due for imminent demolition – so, presumably, security is on-site to prevent break-ins or thefts, or perhaps even to prevent people trying to get in to make a found footage film of their own. It’s boring, but stable work for our two protagonists, each of whom seems to have left their previous employment under a cloud: Lester used to be a cop, and Ed was in the military.

There isn’t much to do. In this environment, every minor sound or shadow takes on a life of its own. Neither does the film go in for making any sudden, flashy moves: it spends most of its runtime showing us that nothing, in this surprisingly large and evocative space, is certain. Long silences pad out any more unexpected noises; seeing, or maybe-seeing things in the corridors almost never comes to any sort of fruition. We get more on the emerging, abrasive relationship between senior and junior employee, mitigated somewhat by the presence of an admin assistant, Ms. Downey (Danielle Kennedy), there to tidy up all the last paperwork which still needs doing in a moribund institution like this one. Gradually – everything here is gradual – we find out that the hospital was notorious for unorthodox experimental practices on its mentally-ill inmates. The film perhaps overplays its hand when it later tries to add further plot points and justifications for the strange ambience in this place, because there isn’t sufficient space for this new information to breathe: strange hospital, murky history is perfectly sufficient. And there are some highly effective scares here, even though you will need to wait until well past the hour mark to enjoy them.

As is traditional, the framing device suggested at the beginning of the film raises as many questions as it answers. This isn’t found footage per se; rather it’s found, edited and soundtracked footage, with an effective, discordant soundtrack which has no reason for being there, unless one of the investigating team is a frustrated filmmaker with a knack for seamless dialogue edits between different cameras and no retakes. But, hey, in other respects the film eschews one of the found footage genre’s most head-splitting features, as bodycams and static cameras never wheel and flounder. (No one ever asks, ‘why are you filming?’ either.) It’s overall a rather understated, often sinister piece of atmosphere building, making effective use of a setting which requires no great interventions to make it ominous, but feels doubly so thanks to the long, quiet ramblings through its floorspace. Ed, a character who seems to begin to break down the second he’s left anywhere on his own, often seems genuinely unnerved: this may be a little of Ed or a little of Paul Syre, but there’s no question that being in this space for a prolonged space of time would no doubt be unsettling, and it works for the film as a whole. There’s as much human drama in Infirmary as anything more overtly horror-related, but the two are definitely wedded together.

Assuredly, this is a film which will be too slow and subtle for all audiences. Go into it forewarned. Suggestion and uncertainty form the bedrock of Infirmary, and it prioritises atmosphere over running, squealing or grandstanding – in fact, all the things which turned me off the found footage genre are things it doesn’t do, and as a result the film is a subtle and often unsettling viewing experience. It’s a promising first feature-length project, one which makes an artform out of never spelling the whole truth out for its audience: that in itself takes nerve.

Infirmary (2026) received its world premiere at the Dances With Films Festival in NY on 16th January.