Late Night with the Devil is an adroit piece of work, a tribute to a time and a place but also an enjoyable and imaginative trip into fantasy, breathing new life into two tired formats – the mockumentary and the found footage phenomenon – by making them entirely engaging and, at least in terms of the film’s structure and purpose for being, entirely plausible. But this isn’t going to be a straightforward review of the film: as fun as that would be to write, this film suggests a different approach. Instead of looking at what works well, and why, this feature will look in more depth at the film’s influences – because that, in its way, explains clearly what works well, and why.

What Late Night with the Devil proves very clearly is that there’s far more to establishing a period setting than adding some analogue technology to your shots. Everything here, from the hairstyles to the house band, from the colour palettes to the props, is meticulously realised. It looks wholly natural – and yes, that goes for the much-vaunted AI content too, which blends in perfectly here (and has attracted more notice than the film’s occult themes, interestingly. I guess every era has its own particular demons). But beyond the film’s solid aesthetics, Late Night with the Devil succeeds because it has also taken great pains to establish a parallel 1970s America, both existing within our history, and outside it. It’s familiar, it’s recognisable, but it’s different: it references well-known American TV shows like the Johnny Carson Show, which anchors it to the 70s we know, the verifiable time period, but then it tweaks and changes other details, building a consistent feeling of estranged familiarity, a kind of uncanny valley of hauntology. From the title of the talk show to the named occultist who features in the footage, everything feels almost real; it’s almost a memory.

Filmmakers Cameron and Colin Cairnes have clearly researched their screenplay very carefully, but where do these details come from? On watching the film, it seemed clear that key events (even if rumoured events) and genuine historical details have been transformed for the immersive and strangely unsettling world of the film. Added to the film’s brilliant use of visual hints and cues (did you catch the decoration on the goblet?) you can find yourself lost in this world or, if you have an interest in the basis for these plot points – read on.

What follows is a rundown in places, a best guess in others, pertaining to the origins of several of the film’s main elements. This will contain some spoilers: be warned!

Ratings wars and The Tonight Show

The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ran for thirty years (1962-1992), and so would have been in its heyday during the period in which Late Night with the Devil is set; it’s an absolutely plausible competitor for Night Owls – though it’s been suggested that the closest inspiration for Night Owls itself was The Don Lane Show. But Carson’s show established the format for the TV talk show which has been picked up and copied by several other hosts, and it also hangs onto earlier forms of entertainment, such as the house band, the compere/comic foil who introduces the host, and the magazine-style rotation of a number of guests (which seems to me to emulate music hall more than it does other television formats, but if you want to appeal to the masses, it seems you’d better give them camaraderie, variety and music). Johnny Carson also established lots of the unspoken norms of conduct for a talk show host: this kind of television offered new opportunity for a kind of negotiated identity, balancing down-to-earth and affable with a range of unspoken but stringently observed codes of conduct: no political ranting, ‘family friendly’ humour, a careful balance with regards speaking about personal life – saying enough, but not too much. We perhaps take this for granted now, but at the time it was developed, it was new. The format has been developed in different ways in the decades which followed – Jon Stewart, for example, made it political, but was then criticised for not being political enough – but the core components, still in use, owe much to Carson. And, back when the number of national television stations was greatly limited compared to today, ratings were really significant. There were just four major television networks in the mid-Seventies. Everything else was local or public access, with decidedly different budgets, purposes and approaches.

When a successful show could command multiple millions of viewers at any one time – over twenty-two million households were watching Happy Days in 1977 America – then this was of great interest to advertising, hence the frequent breaks in Night Owls to hear ‘a word from our sponsors’, a viewing model we have all been raised to expect. This led to a phenomenon, also referred to in the film, as Sweeps Week, a large data-gathering exercise pioneered by the A. C. Nielsen company, who invite households to record their viewing habits: this material is then sent off and collated, allowing greater demographic understanding of audiences and their likely spending habits. How useful this is now, in the days of Netflix and viewing on demand, is moot: in the mid decades of the twentieth century, Sweeps Week was the single biggest indicator of a show’s success, in that advertising underpins so much of the entertainment industry.

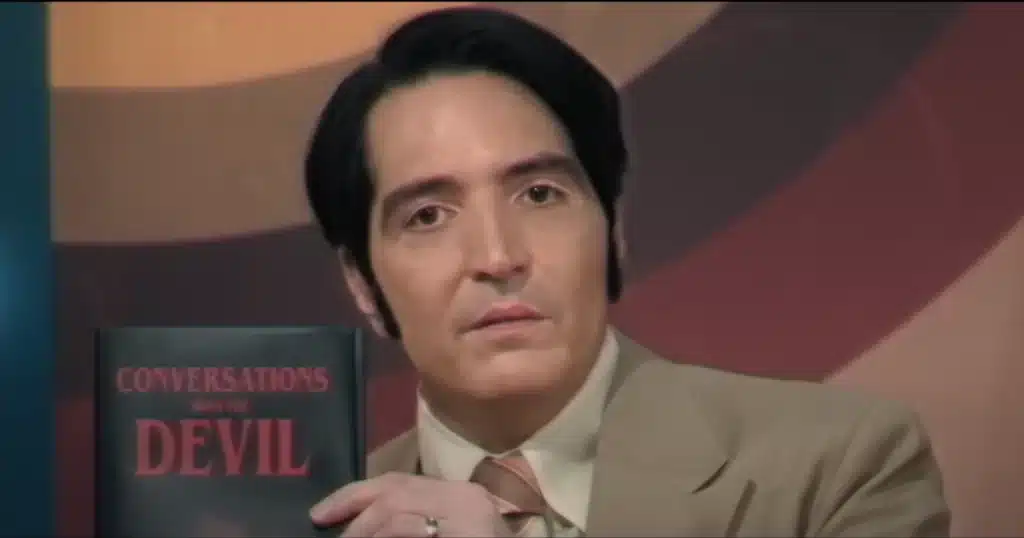

Jack Delroy (David Dastmalchian) sees success in Sweeps Week in two ways: a marker of his personal success, and an assurance of money, money, money coming his way. Securing a vast share of the viewing figures cements his comeback, means more shows, more income and more celebrity (which is often a reflection of earning power anyway). That he continually references Carson gives us a plausible competitor, at a point in history when Carson was enjoying his heyday within a TV format he’d helped pioneer; Sweeps Week, too, is a real phenomenon showing how impossibly tangled fame and fortune really are. And, even had the Halloween special gone to plan (though perhaps it went to plan for someone), it carries within it the future echoes of the sensationalist talk shows to come, offering up ever more scandalous subject matter for the increasingly interactive responses of live studio audiences.

The Age of Aquarius and the psychic revolution

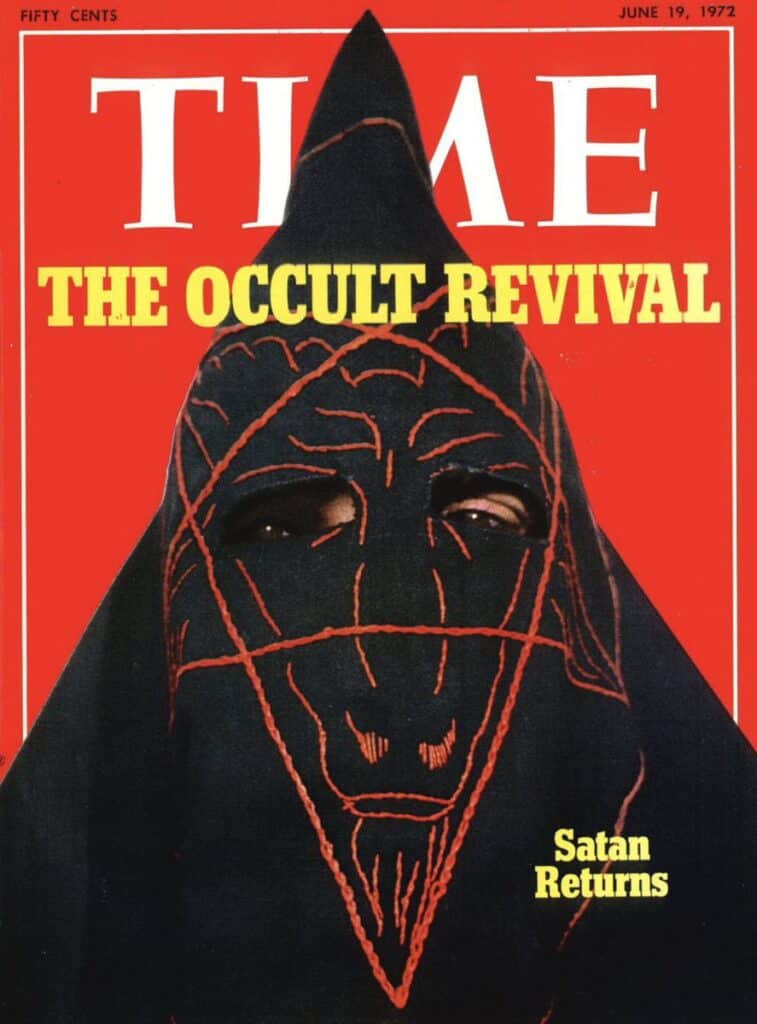

But let’s come back to the subject matter of the Night Owls Halloween Special for now. Halloween has long been an opportunity to generate some on-screen sensationalism, but coming as the show does during the mid period of the Seventies, Night Owls is well-placed to take advantage of the era’s new relationship with the occult. The hippie movement had, by 1977, already migrated into the mainstream, and post-Manson and Altamont a lot of the hopeful revolutionary shine had disappeared, but as it became established as a trope of sorts, so had many of its accompanying tastes and ideas. The hippie fascination with alternative spiritualities, particularly Eastern belief systems, had seemingly opened the door on a host of other beliefs, with a renewed interest in witchcraft and the supernatural also making its way into mainstream America. A decline in Christianity throughout the Sixties and Seventies only compounded this trend in the minds of many. In 1972, Time Magazine ran a special issue on the ‘Occult Revival’, replete with masked cultist on the cover. ‘Satan Returns’, read the caption; this came just six years after their similarly controversial cover which asked, Is God Dead? Elsewhere, less edifying publications were dabbling with the same topics – pulp fiction and lowbrow magazines went wild with covens and demons – and in cinema, too, horror explored Old Scratch’s new heyday, with The Exorcist scaring a generation back to Church in 1973 and The Omen popping up in 1976. But perhaps the film with the greatest kinship to Late Night with the Devil – at least in terms of the documentary framework – has to be Witchcraft ’70.

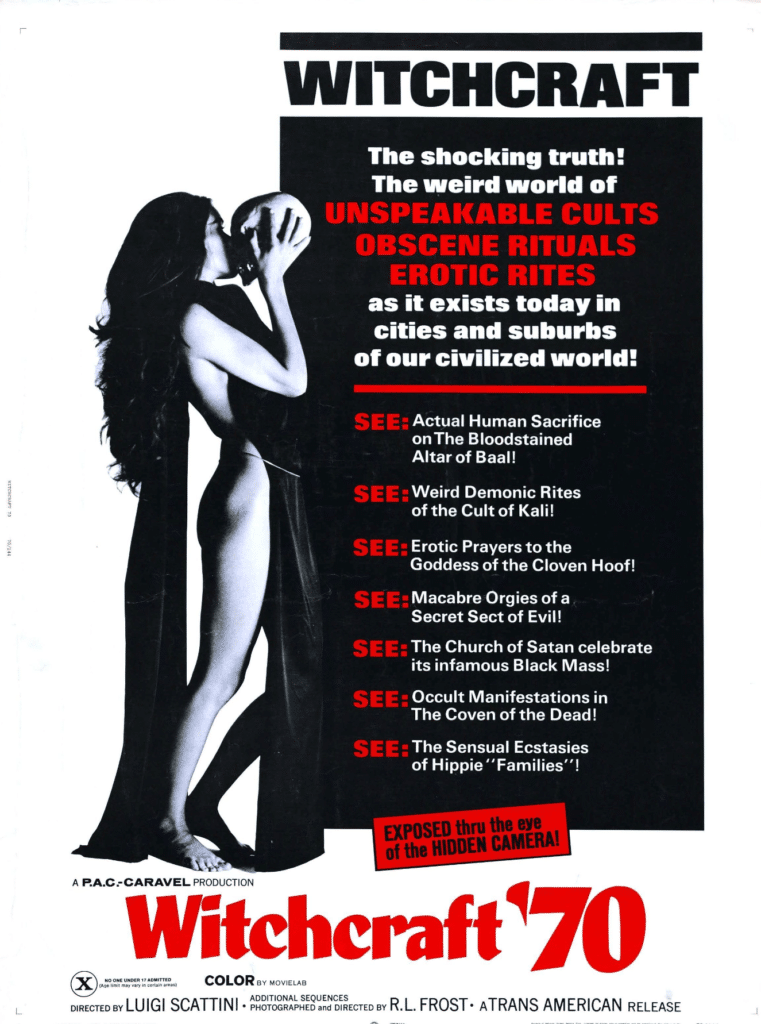

Witchcraft ’70 is not a narrative film; rather, it followed in the new and burgeoning tradition of mondo cinema, a kind of exploitation film which spliced serious documentary with often graphic, salacious or otherwise rarely-seen footage. Mondo Cane (Dog World) got the ball rolling in 1962 and provided hopeful filmmakers with a cheap and fairly easily-realised model which enabled them to pore over acts of extreme cruelty, often with a chaser of – and it’s odd when you think about it – naked flesh. By the by, Late Night with the Devil‘s opening credits reference another mondo-type film, The Killing of America, but that particular film is more appalled by serial murder and race riots than anything more magical. Well, Witchcraft ’70, or to give it its other titles, The Satanists and Angeli Bianchi, Angeli Neri, focuses quite openly on the more salacious, or ‘erotic’ rites associated with modern forms of witchcraft. This makes sense in terms of shifting tickets; along the way, it serves as a partial, but interesting and relevant kind of time capsule of occult beliefs at the end of the 1960s, incorporating hippy culture alongside various cults which apparently worshipped Baal and Kali; there’s also space for the biggest anti-hippy of them all, Anton LaVey and his Church of Satan. Whilst LaVey wasn’t a theist, he wanted Satan at the helm as a figure of strength, individuality and fear; he loathed lax and indolent hippie culture enough to ritually curse the high priest of acid, Timothy Leary. But in this film at least, we have hippies keeping company with the earliest CoS members. In many respects, then, Late Night with the Devil reflects some of the material shared in Witchcraft ’70, and in particular, the CoS footage. The ominous Abraxas cult leader shares some similarity with LaVey. The priest’s name – Szandor D’Abo – clearly reflects LaVey’s full name, Anton Szandor LaVey.

As for Satan himself, he’s conspicuously absent from a film titled Late Night with the Devil, which is curious – but, again, this seems to reflect what we see in Witchcraft ’70. Look at the poster above: given that Baal is a pre-Christian deity of fertility and Kali is a Hindu goddess, it’s clear that our cultists are prepared to play fast and loose with whom they worship and as such, it makes all kinds of sense that Late Night with the Devil opts to foreground Abraxas, the Gnostic ‘god above all gods’, an ambiguous figure co-opted here to stand in for the older idea of the deal with the Devil. If it is indeed emulating Witchcraft ’70, then it does so gods and all. But Late Night with the Devil nonetheless plays with the idea of the Faustian pact. In many respects it almost doesn’t matter what entity is selected for the purpose; the deal is the thing, and where Satan isn’t used or isn’t amenable, perhaps, other figures are available; filmmakers also seem drawn to the great variety of entities to choose from, which might explain why Hereditary plumps for Paimon, a lesser demon who had not, until that point, had his moment in the sun. For many viewers though, both in the semi-fictional universe of Late Night with the Devil and for us, too, even now, any entity under discussion, by virtue of being ‘not the Judeo-Christian god’, is prefigured as the Devil. And the Devil has such a long-established track record as a tempter, after all. Who could be better to offer one’s material and carnal desires, now so often wrapped up in ideas about career, fame and celebrity, than the world’s most famous rebel, who launched his own start-up and has stayed in healthy competition ever since?

The future of cults and the Satanic Panic…

However, once Late Night with the Devil‘s framing narrative establishes that the Abraxas cult, led by D’Abo, ends in a siege and a fiery demise for most of its adherents, it moves quite sharply away from the worship of any number of entities, Satan included, and shifts tack towards recorded instances of Christian fringe groups which have ended the same way. Satan is rather underrepresented in mass deaths, unless you believe that he does most of his dirty work underground (see below). Rather, it’s the likes of the Jonestown Massacre, still a little way ahead of the timeline of the film but now part of our cultural memory, as is what happened to the Waco complex in the early 90s: the extremist and fringe beliefs born during the 70s were about to foment into genuine violence and oppression. But back to the film’s cult of choice, and another indicator that the filmmakers are confident to play with upcoming events and obsessions, making the timeline of the film feel faintly familiar, as well as ominous.

The survival of a lone girl, Lilly (Ingrid Torelli), the only member of the cult not to be burned to a cinder, prefigures one of America’s strangest psychodramas – the Satanic Ritual Abuse phenomenon, which itself spread like wildfire throughout society, acting rather like a mondo title: passing off the most salacious, unlikely content via a respectable moral framework and the efforts of the new priesthood, psychiatrists. It’s okay to read this kind of thing if you’re coming from a place of concern; of course, many of the medical professionals who lent their names to accounts of Satanic cult activity genuinely believed that they had uncovered something awful, and that they were acting morally in helping ‘survivors’ work through their issues. Many others who found themselves involved in the Satanic Abuse claims, peripheral or otherwise (and again, talk shows played a sizeable role in establishing many of the most significant speakers and their claims) probably believed enough to give it all some credence, genuinely wanting to protect the vulnerable and to head off any further cruelties. Others will have spotted a quick buck and acted accordingly. However, the likes of Michelle Remembers kickstarted something pernicious, as well as establishing the typical double act, victim-plus-professional, wild accounts given with one hand, estimable and rational framework offered with the other.

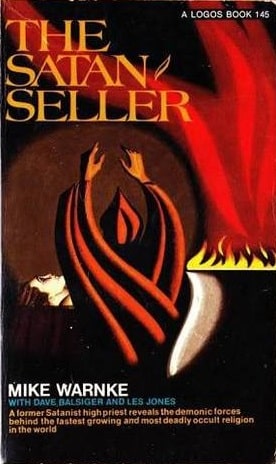

Michelle Smith may have been an adult when she gave her account in 1980, but she was always clear that the events she had been helped to recall related to her childhood. As such, Lilly’s age in Late Night with the Devil brings an immediacy to the Satanic Abuse idea at play in the film, but is wholly in keeping with many of the most influential accounts of same, many of which pre-dated Michelle Remembers and seemed to rely on the febrile atmosphere of a reactionary impulse in America, already whetted by McCarthyism and the shock of the new, then nurtured into a different form by the rise and rise of fringe religious beliefs and, let’s face it, the growth of occult horror too, with its threats of secret cabals of Satanists extolling ordinary Americans to just participate, or its Satanic incursions into normal families. A book which prefaced a lot of this came out in 1972: serial husband Mike Warnke’s book The Satan Seller purports to be a memoir by a ‘former Satanic high priest’, and garnered a lot of interest before people examined his claims too closely. But Warnke certainly helped set the seal on Satanic Ritual Abuse’s key superpower: anyone who criticises the idea too vociferously is probably in on it.

Meanwhile, more cynical authors and psychologists attempted to make sense of the phenomena by casting an ostensibly more scientific eye over accounts of ritual activity; in the film, Dr. June Ross-Mitchell plays such a role, coming from the perspective of parapsychology, another burgeoning academic field during the 70s. Parapsychology tries to negotiate a route between the supernatural and the scientific, and the 70s saw a surge in interest in the field; even the Stanford Research Institute was getting in on the act during the decade.

The Grove

Nonetheless, whatever perspective taken – true believer, traumatised survivor, detached observer – the sheer tenacity of belief in secret cult activity, one which has stuck with us, points to entrenched anxieties about power and control, often framed by sex, violence and whatever else troubles polite society at any given time. Rumours of secret cabals and Satanic allegiances continue to trouble the most unlikely people, such as Taylor Swift, whose great success must be due to the devil (though to be fair, it is a puzzler else). But that brings us back to Delroy’s own rumoured cult activity, a subject which helps to frame the film as a whole. As the documentary element of Late Night with the Devil suggests, Delroy has been out to play with the great and the good in a place called The Groves, a clear nod to the real location of Bohemian Grove, playground for some of society’s most influential men.

In fact, quite a lot is known about Bohemian Grove, even if what we do know has never exactly satisfied the genuinely curious: any such gathering of the powerful, in a secretive and remote area, protected by high security, is always going to tantalise the excluded. To make it more alluring, there’s often a waiting list of around fifteen years to become a member: little wonder the conspiracy theorists find plenty to do with this one. What are these powerful men doing out there, amongst the trees?

Late Night with the Devil imagines what they might be doing, melding acknowledged activities such as the Cremation of Care performances (where members symbolically celebrate the ‘salvation of the trees’ with a cathartic theatrical show) to more sinister imaginings, of which there’ve been many, given the possibilities for interpreting the group’s use of pagan imagery along decidedly sinister lines. Fun fact: the organisation’s emblem is an owl. Factor in the opportunity for networking with many of the most powerful men in society and it’s not hard to turn the whole thing on its head: they’re not there because they’re powerful, they’re powerful because they can be there. The requirement that ‘Weaving spiders come not here’ – meaning people seeking to cajole and to network should leave their ideas at the gate – seems like a big ask, and almost certainly some networking must take place in such a relaxed, intimate and private setting. So why not go further, imagining all manner of ritual activity taking place amongst the trees? If Satan can infiltrate the average American family, then of course he – or a chosen representative, as in the film – can wheedle his way into a gathering of those with serious influence. Hence the ways in which ideas about Bohemian Grove morph into The Grove during the film.

Lilly – as an unwitting messenger for the pernicious and devilish influence she brought with her from the Abraxas cult – certainly recognises Jack Delroy. In fact, she speaks to him familiarly, immediately feeling that she’s on first name terms with this man despite him being decades her senior, and reveals to him (as ‘Mr. Wriggles’) that they have already met – out amongst the trees. It’s clearly suggested that Jack has in fact been ‘weaving’, and has made unendurable sacrifices in the name of his career – a pact, one which is now coming full circle, given his grand success in the ratings. Take away all the trappings of modernity, though, and it’s the oldest trick in the book – paying the price for an ill-gotten lurch in success. The film plays it out brilliantly by melding notions of devil worship, cult activity, possession, psychical research and sacrificial magic, all against a backdrop of TV and audience figures which may not have the same hold it once did, but still means something to modern audiences. It’s old magic meets new.

James Randi and the Committee for Skeptical Enquiry

But the Seventies weren’t simply an era of blithe acceptance of magical or paranormal beliefs: as soon as a new strata of hucksters and chancers established themselves on the often lucrative fringes of mainstream belief, sceptics emerged to attempt to keep them in check. Punishing the sceptic is of course a mainstay of horror cinema, but outside of the horror genre, there were several figures very much like Carmichael Haig (Ian Bliss) who made it their business to disprove what they saw as the exploitative and heartless manipulation of often down-at-heel or grieving people, open to suggestion in ways they would never ordinarily be. Whilst there are several possible models for Carmichael Haig, however, the most likely candidate must be James Randi.

Randi – who perhaps topped his whole career by proving there’s no afterlife either, by conspicuously failing to come back to sue the Fortean Times for the scandalously unkind obituary they printed about him in 2020 – started, like Car Haig, as a magician, learning the tricks of the trade – before breaking ranks, founding the Committee for Skeptical Enquiry in 1976 and, oh, frequently appearing on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, in much the same capacity as Car does in Late Night with the Devil. A clever and confident man, Randi had absolutely no truck with what he saw as hokum, and so for believers in the paranormal would have come across as arrogant, but where you adjudge arrogance and confidence can be wholly subjective.

Most tellingly of all, Randi’s Educational Foundation (the JREF) also kickstarted the One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge. First offering the amount of $1000 in 1964, Randi kept on increasing the amount on offer as the decades passed, offering $1000, then $10,000 (Lexington Broadcasting added to the pot) and finally, no doubt buoyed by decades of keeping hold of the money, the final amount rose to a million. To get the money, you had to provide evidence of a supernatural ability under certain, agreed criteria; despite around a thousand people volunteering to try, the money was never won; critics of Randi have suggested that the money never existed, though considering Randi’s targeting of high-profile psychics like Sylvia Browne, it could equally suggest his certainty that no one could ever win it. Randi also had a long-running ‘challenging relationship’ with famous spoon-bender and psychic Uri Geller; a Geller-alike also features momentarily on Late Night with the Devil. To see Randi at work – often in a talk show format – click here, with the famous cheque being produced from his top pocket at 4:27. There’s also video of his appearance on The Don Lane Show, to bring things full circle. In the real world, as in the overlapping world of the film, the TV chat show is a strange place, reflecting strange times.

Of course, things never went awry for Randi as they did for Haig – to put it mildly! – but the presence of a vociferous cynic on the set of Night Owls certainly completes the time capsule, giving us the full microcosm of weird and fringe beliefs which was taking hold of the popular imagination at the time, playing them all out in a glorious and graphic series of ‘what ifs?’