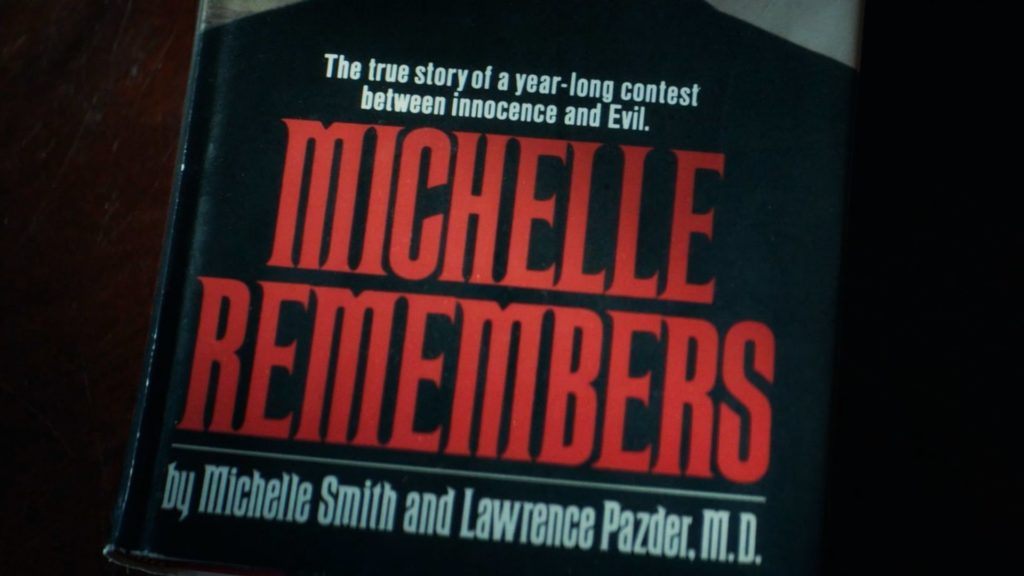

The ‘Satanic Panic’ of the latter decades of the 20th Century serves as a deeply unedifying lesson in paranoia, exploitation and groupthink. It also reminds us of the human capacity to ignore the overt to fantasise over the covert: this impulse is still with us, now aided and abetted by the internet and social media; Pizzagate was and is, if anything, even more outlandish than its predecessor, even if (for now) failing to make such an impact on mainstream media. As such, Satan Wants You is a gripping, often exasperating, and a very important watch. It charts the birth of this phenomenon via one outlandish book, which is explored at length here.

Probably the toughest thing about writing this review is summarising just what this book – Michelle Remembers – was, how it came about and what its legacy has been: even though conspiracy theory rolls on in modern life, we do live in a different world to the 1970s in many key respects, and certainly in our expectations around doctor/patient relationships (though I would argue that our increased desire for therapy keeps the door open for less scrupulous, less professional players to exploit us; there’s always a new grift).

The book was written as a result of a collaboration between a patient – Michelle Smith herself – and her psychiatrist, Lawrence Pazder. Opening the film, podcaster Sarah Marshall introduces us to Michelle and her recovered memories as the ‘patient zero’ of the Satanic Panic. Back in 1976 (the Satanic Panic is perhaps best-known as an 80s phenomenon, though the book pre-dates this period) Michelle began making claims about a slew of horrific memories – cruel, even absurd events which happened to her during early childhood at the behest of a highly secretive (of course) Satanic cult. Forgotten by her until this point in her adult life, Michelle was able to recall what occurred thanks to the special, unorthodox therapy sessions offered to her by Pazder; Pazder encouraged her, recorded her, and to a large extent refracted her scattergun recollections via his own experiences, ideas and beliefs. The book itself is a summation of this process, a folie à deux perhaps, only one latterly influenced by power, money, influence and – lust.

The book was a sensation; well of course it was, as it made claims about a well-organised, vicious, hidden cabal of devil worshippers operating in North America; people, being people, can’t help themselves. It also had a bulletproof justification for all of its lewd, bloodthirsty content – a defensible front, as this was Michelle ostensibly warning society about the nefarious goings-on in its midst. Speaking to Michelle’s sister, the film is able to glean some vital context for the type of person Michelle became as an adult; theirs was an unhappy home, with lots of house moves, a violent, alcoholic father and a downtrodden mother; this, maybe, goes some way towards explaining some of Michelle’s traits – but this is just a small part of the whole.

Steadily, a picture emerges of the early relationship between Michelle and religious faith; when she began to make her claims about Satanic abuse, the Catholic Church, perhaps already buoyed up by a newly-devout (read: scared) flock due to The Exorcist in ’73, was more than ready to give her complete credence (the Pope himself offered a foreword in Michelle Remembers). So it wasn’t just Pazder, not even in the early years, as fundamental as he was to the new life which unfolded before Michelle (and which he enjoyed alongside her). Tours, talks, travel, but perhaps most of all wealth and influence came along in quick succession. A rather more complex representation of Michelle comes out at about this point: was she simply a pliant, authority-motivated people pleaser, or was there more to her? How motivated was Michelle by her interest in Pazder in a capacity beyond being just her psychiatrist? How responsible was the Venn diagram between organised religion and psychiatric medicine? In interviews, but particularly in her transcripts, Michelle is as apologetic as she is grotesque, but – as it comes across from Pazder’s not-wholly-unbiased ex-wife and daughter – not above attention-seeking, and certainly not above selfishness. Families, including theirs, were destroyed by the book’s legacy.

Elsewhere, Michelle’s story led to a great blossoming of unreason, a snowball effect which went so far as to have people guarding newborns in British Columbia against Satanic cult kidnap; no one, it seems, with the exception of the Church of Satan (who actually brought a defamation lawsuit against the book) dared cast doubt on any of this. It was all too mysterious, too salacious; to call it out was maybe to suggest that you were a Satanist yourself. How do you win that one? Speaking on behalf of the CoS, Blanche Barton is a welcome voice of reason throughout.

Whilst you could come to this film as a complete outsider, knowing nothing about the topic, my feeling is that Satan Wants You is somewhat more for those already aware of the Satanic Panic and its origins: it gets going quickly off the bat and keeps up this pace and detail across its ninety minutes. A visually very smart documentary, it’s impeccably shot, edited and soundtracked, with old footage, new interviews, on-screen text (excerpts from transcripts, interviews and sections from the book) and lots of material which will certainly not have been seen by many people, or not in one place at least. Thorough and expansive, with a keen undercurrent of disbelief that this ever unfolded the way it did, Satan Wants You follows the story right through, covering its twists and developments in suitable detail. It feels very fresh and new. And perhaps it should, because this kind of paranoid racketeering never feels fully past tense. It can’t fully answer the ‘why?’ but it shines a light on what happened, and perhaps could happen again. This is great work by directors Steve J. Adams and Sean Horlor.

Satan Wants You featured at the Fantasia International Film Festival 2023.