By Keri O’Shea

Portraiture of tyrants from history is a curious thing indeed; so often, what we see in their paintings seems to belie what you might expect, given their recorded character traits. There are of course lots of reasons for this: painting techniques and styles, the ideals of the day, and of course issues relating to the sitting itself. You’d hardly be likely to paint Mehmet II warts and all if you thought your intestines would end up spilled all over the palace floor for your troubles, after all. Still, and even accepting that all historical sources have their limitations, it’s interesting to consider the distance between the reputations and the appearances of some of our better known despots. Vlad Tepes, the Romanian voivod, stares with purpose out of his best-known depiction, but the face hardly matches up to his known excesses. Erzsebet Bathory – the 16th Century noblewoman alleged to have bathed in the blood of young women to stave off her own ageing – has come down to us via a portrait which suggests petulance at worst, a child-like serenity at best. The incongruity between the faces and the deeds is vast.

Another such figure (and one with several similarities to Tepes, incidentally) is one of Russia’s most infamous, and yet still celebrated rulers – Ivan Grozny. The name itself is most commonly translated as ‘Ivan the Terrible’ in English, although Grozny is probably more accurately translated as ‘tempestuous’, as it has its origins in the word ‘stormy’ – perhaps similarly to how in English we might positively describe someone as a ‘whirlwind’. Regardless, Ivan the Terrible it has become. This 16th century ruler – famous for uniting the Kingdom of Russia and for dealing with the sprawling, corrupt power of his nobles – has, like many comparable figures, a legacy of brutality to balance his positive actions. His cruelty and paranoia have become legendary. And yet, as with the other figures mentioned here, contemporary portraiture shows him as a benign, passive figure, heavy with the vestments of the Russian Orthodox Church. He hardly looks like someone who could have been a living figure, let alone someone guilty of the worst crimes – including filicide.

The human animal is by nature more appalled by instances of individual cruelties than by cruelty on a mass scale. We can to an extent surpass it, but it seems like we are hardwired to respond to wickedness in the detail. This is perhaps why, even from a man who has been known down through the centuries for widespread acts of barbarism, it is the fate of his eldest son – also called Ivan – for which he is most infamous. Ivan Grozny, perhaps unsurprisingly known for having a vile temper, quarrelled with his son one day at court. As young Ivan remonstrated with his father, Grozny in a rage struck the young man on the head with a heavy walking cane – probably fracturing his skull. Young Ivan died of his injuries almost immediately, leaving Grozny without the heir he had deemed most suitable and meaning that he would be succeeded by his second son, a young man ‘mentally unfit’ for the task. In effect, this one moment’s deed deprived him of a son he loved and of any confidence he might have that his legacy would be passed on. Whatever we might know or indeed think of Grozny, we can imagine how devastating this would be, and the gut-wrenching regret he will instantly have felt.

It took three centuries before this scene was committed to canvas with the gravitas and horror it deserved. The man who proved himself able is arguably Russia’s best-known painter, certainly its best-known Realist painter. That man was Ilya Yefimovich Repin, who returned to historical painting in 1885 to complete ‘Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan’. It is to my mind one of the most haunting pieces of art ever created.

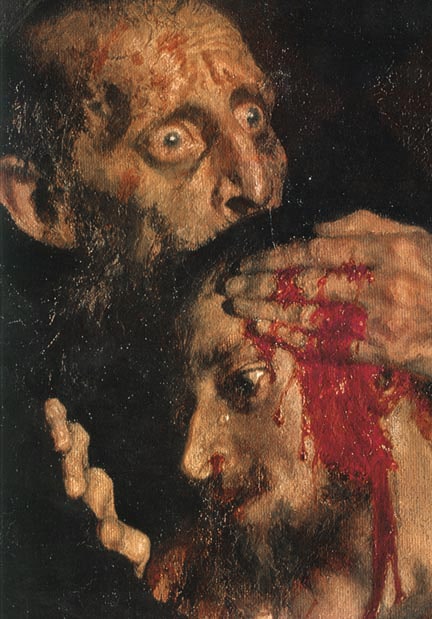

The differences between the Realist style used here and the idealised, unrepresentative portraiture of the day is exaggerated hugely by the savagery of this piece. Repin chose to paint the exact moment of Grozny’s revelation; the awful moment of stillness after the manslaughter of his heir. The two men, one living, one dead, are presented alone in a room whose fire-lit warmth gives the lie to the scene and its circumstances. That warmth, and its crimson finery is ironically juxtaposed with the blood on young Ivan’s head, which is the brightest red here, and the rich, geometric-patterned drapery in the background forms another contrast with Ivan’s curved, inanimate body, fading into nothingness before the grisly focus of the scene. There is evidence of a struggle; furniture is upended, and Ivan’s leg has disarrayed the silk rug beneath their feet – but now all is still. Horribly, terribly still.

However, for all of that, it is Grozny’s haunted expression which retains its capacity to shock. His wide eyes stare into nothing, he is lost in his thoughts; those eyes contrast utterly with the now unseeing eyes of his son. There is a lone tear on young Ivan’s cheek, as he is cradled in death by his now-penitent father, Grozny’s hands clasped ineffectually to the fatal wound. Even knowing the circumstances of this crime, I find Grozny’s expression deeply moving. To my mind, it seems like a Realist take on the Goya painting ‘Saturn Devouring His Son’ – the same blank expression, the same desperation, the same destruction of one’s young. It also creates something which often features in horror – sympathy for the monster, regardless of their deeds. This disturbing image has shocked many through the years; not least, in 1913, when Grozny’s face was badly slashed by a man called Abram Abramovich Balashov. Balashov was removed from the scene shouting, “Enough blood! Down with blood!”

Conventional portraiture has long been restrained, limited, concerned with mythologising rather than with representation. By reversing this process – turning a mythologised man into a human being – Repin has crafted one of the most arresting historical paintings ever. Here, we have a man bereft, appalled by his own immense and self-stifling cruelty just as we are appalled by it. It’s a moment of abject horror; Grozny will stare forever into the abyss, an emblem of the moment after the storm, the terrible understanding that one has to live forever with one’s actions. Repin has made a man out of an icon, then he has made his suffering iconic. The result is haunting in its poignancy and intensity.