On occasion, a film comes along which makes an almost immediate, indelible mark. As soon as it appears, it disrupts what came before it; it can be difficult to even remember a time before it, so quickly do its characters and archetypes take hold. Such a film was Ring (1998), coming at the tail end of a decade where the most popular style of horror was, overall, markedly in contrast to Ring’s own brand. Audiences were ready for something else perhaps, something outside of the remit of ironic slashers and what I’d say really was a ‘post-horror’ film, Scream, which wove a hefty amount of mockery of horror into its own horror; it’s for its fans to argue that this was all in good part. But a shift was coming, and the new, largely unknown Asian horror phenomenon was about to engulf waiting Western audiences, keen not only to have their horror become more varied, more authentically scary, but to have it come from a place hitherto-unknown beliefs, folklore and mythology. With Ring, J-horror as we now know it was born: vengeful, horrifying spirits slithered onto our screens, acting according to motives and codes which were mysterious even to the young, modern, forward-facing Japanese characters being subsumed by them, and doubly so to us as Westerners. Other nations were quick to move, with other Far Eastern countries – South Korea, Thailand, The Philippines – soon bringing their own stories to the screen. But, arguably, interest in Far Eastern horror started with the international success of Ring.

Ring: a modern-day curse

Ring itself was based on a 1991 novel by Koji Suzuki, whose career has been to some extent defined by his trilogy of works Ring, Spiral and Loop; he returned to the Ring universe in 2019 and 2020, turning to manga to further explore the character of Sadako. However, for the film version, several key elements from the trilogy are significantly pared back; the novels invoke the theme of illness and transmission quite heavily, whereas Ring (1998) dispenses with this. The film excises the idea of disease to render Sadako an agent of pure, unadulterated hatred. This is what she spreads and this is what kills.

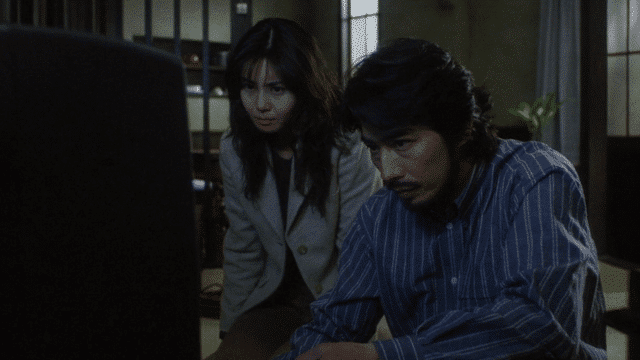

The film begins with two schoolgirls discussing a rumour of a ‘cursed videotape’; a run of false starts come from the TV and the landline phone as they talk, preparing us for the idea that all technology can be scary here, as it offers up a series of alarming incidents even before it acts as a conduit for something supernatural. One of the girls is niece to journalist Reiko, and we see her researching the same urban legend – the cursed tape, as described by a run of schoolchildren, who channel the same hearsay and rumour which feels familiar from similar interviews during the ‘video nasties’ debacle in the UK, just over a decade earlier. You just don’t know whether you can trust in the veracity of children this young and swept up in something so exciting; Reiko, still a clear-headed cynic at this point, notes that traumatic events, such as major accidents, often trigger these kinds of rumours. But she gets drawn in; her family connection is one thing after her niece’s sudden death, but then she makes the rational error of trying to substantiate one of the other assertions that another mysterious death has recently taken place, also linked to ‘the tape’. As so often in horror, reality crashes down in opposition to unreality; one becomes the other. She tracks down the video for herself, and views it.

Once it begins to slowly dawn on Reiko that the curse may be, somehow, ‘real’, she knows that she only has a week to find out what, if anything, she can do. Her problems are horrifyingly compounded when she discovers her young son watching the video too: the film at this point turns into a battle for a family’s survival. But, this family is not a happy one, and its own damaged state becomes apparent.

Who can Reiko turn to? Her situation gives us a glimpse of a fractured family unit; her young son, Yôichi, can’t be more than five or six years old, but he’s routinely left at home alone so that his mother can work and then, later, so she can delve into the backstory of the videotape. This kid is an end-level boss latchkey kid, alone well into the night, and most of the contact between his mother and him comes down the phone, with her routinely apologising for being absent. When Reiko needs help, she asks her ex-husband Ryuji; Ryuji, Yôichi’s father, has no contact with his young son whatsoever, at least that we see. Whilst their thoughts turn to making some provision for the little boy should they both imminently die, it feels oddly like an abstraction. Yuji muses, at one point, that it might be better if the whole family unit ‘dies out’. Perhaps equally tellingly, Ryuji often refers to Reiko by her patronymic, rather than her first name. They are seemingly more drawn to the story behind the video itself, and as they finally track down Sadako’s story and then her mortal remains, Reiko spends a moment cuddling Sadako’s remains almost fondly. It’s the only moment of nurture in the film. As much as Reiko does seem to love her son, we see her shaking him and grabbing him, rather than holding him as she does Sadako’s ghastly, long-haired skull.

There’s another broken family story concealed here, finally revealed to the audience as Reiko and Ryuji uncover it. Sadako herself, we glean, was murdered by her own proxy father; her own relationship with mother, the psychic Shizuko, is virtually unknown save for some evidence of bizarre loyalty on Sadako’s part, when she successfully wishes one of her mother’s critics dead. So the film is riven with family trauma; it’s one of its saddest, most significant moments that, once Reiko has identified the secret of surviving the videotape – at the cost of her ex-husband’s life, no less – Reiko is going to sacrifice the only loving family member Yôichi has, his grandfather. Why him? And what sort of a life would this mother and son go on to have, after doing that? The bleak cycle of emotional deprivation seems set to spiral on, thanks to a film which is as rationally bleak as it is supernaturally fearsome.

Analogue horrors

It’s interesting that the film’s use of technology is so integral to its horrors, but also that it is a film poised between two worlds – analogue, and digital, which was at that time already beginning to take hold. Mobile phones were rudimentary, but more and more people were starting to use them; the internet, too, hadn’t gotten its hooks into everyday life the way it does today, but it was there – simplistic, but functional, and offering new possibilities for promotion, as The Blair Witch Project – another significant, game-changing supernatural horror – was to prove in the following year (some of the early faux webpages designed to push the idea of a genuine Blair Witch mythology were as sinister as hell, and spread like wildfire.) Clearly Hideo Nakata would have been aware of the potential of the internet and for new kinds of communications to work with the flow of his film, although, granted, his film was based on a book which was released at the other end of the Nineties. But Ring is avowedly analogue. It’s one of the last films, perhaps, with a contemporary setting which can plausibly ignore the rise and rise of mobile phones, digital cameras and the world wide web.

It’s not amiss. In the late Nineties, analogue was still being used. It was still the norm for many people. Analogue technology today has become a cumbersome fetish for many filmmakers, who include it because they think it’s quaint in some way, some kind of nostalgia trip, or a cheap shortcut to a ‘period’ setting which they seemingly can’t resist. But for many young filmmakers working today who may have seen Ring at a young age, perhaps it’s here that analogue tech really crept into their consciousness, despite the fact they probably saw it a couple of years later, when video cassettes were already being consigned to the scrapheap in favour of DVD. Certainly, in a lot of films being made now – where analogue technology is the focal point of the set or the plot, the filmmakers seem inexorably drawn towards the frightening potential of the video cassette itself; V/H/S 99, made very recently, seems to positively glory in the static, the clunks, the interference, the audio issues of its fake video framework. But here’s the thing: video was uniquely creepy, and one of the reasons Ring works is because it exploits that so effectively – and organically, because it was still a part of people’s lives.

The capacity for people to copy videos – I remember them, player running to player in real time – opened a floodgate not only for people to capture films and programmes from television (which they may never see again, in some cases) but also to share them. Friends of friends would pass them along; magazines would carry ads from people offering to fill a cassette tape with varying-quality horror or other banned material for a few quid. You could sign on for a mystery prize, you could go off titles alone, you could end up with something almost entirely different to what you might have expected. A snippet of an unrecognised film, when seen, could take on weird new significance; you’d remember it for years. But even old, generic cassettes at home, with no label, or blank cardboard sleeve, could be a source of mystique and there was often something disorientating or even disturbing about them. It’s no accident that the video tape Reiko discovers at the cabin itself has no label and a blank cover. Amongst the small video rental library, it stands out, its lack of markers suggesting something strange about it.

Videos operated as a kind of palimpsest, open to being copied again and again, with new clips overlaying old. None of this was neat and tidy; often you’d see tantalising fragments of what came before, appearing suddenly and disappearing as suddenly. The picture and audio could break down, dissolving and distorting before coming back to clarity, and there was no widespread, reliable way of ever discovering what those fragments were. Today, no video clip is a mystery for long; people can use the internet to discuss it and define it; there’s a comfort in being able to ground whatever you’ve seen in the babble of other people. Even if they’re not correct, the dialogue itself shrugs off the feeling of mystery, and places whatever-it-is back in the everyday. That couldn’t happen to the same degree before the internet was better-established, and things couldn’t be simply looked up. Video was, as such, rife for urban myths and legends, scaremongering and exaggeration. It’s fertile ground for the horrors of Ring, and is used to full effect. The cursed video clip itself, shot on 35mm, was made extra grainy in a laboratory to give it the right copy-of-a-copy feel.

A lot of time in the film is spent debating the existence of the cursed video itself. Ryuji, who is a rational man (before he reveals his own psychic tendencies) affirms the obvious: “it’s a video. Somebody made it.” He and Reiko deliberate over it, frame by frame, trying to decipher its message, if it has one (which it doesn’t; it’s a snapshot of unbridled resentment and anger, Sadako’s hatred literally burning a series of jarring images and sounds onto the nearest available imprintable media). But as they pore over the video, it does begin to offer up clues as to its provenance, even if its message – in its totality – remains chaotic. A woman combs her hair; the word ‘eruption’ scatters across the screen; bodies crawl; a man, his face concealed, points at something unseen, and the word ‘Sada’ briefly appears. The inclusion of a well, off on its own in the middle of the frame, is another mystery. It is nonsensical, mysterious and – utterly horrifying, a real jolt to the system. It is frightening. You don’t need to instantly be able to interpret this to feel weirdly unsettled by it. But, hidden in the audio, Reiko and Ryuji recognise fragments of a dialect only heard on Oshima; they are able to track the story lurking in the corners of the video there, heading to Oshima Island to investigate further, with a view to somehow, perhaps, evading the curse.

The video is by no means the only analogue technology used in the film, as vitally important as it is. Viewing the video triggers a mysterious phonecall: this is the beginning of the countdown to the curse running its seven-day course. The call itself has no language; it simply emits a terrifying noise. And, significantly, this only affects landline telephones; these, too, can suggest mystery where there’s no indicator of caller ID, and not hearing a speaker allows the imagination to fill the gaps, often guessing an unpleasant intent (the phenomenon of the ‘heavy breathing’ call used to be much more prevalent, given an added layer of malignancy by suggesting that the caller knows, somehow, that you are at home. In a way, these kinds of malign nuisance calls can feel like an element of home invasion.) The curse never bothers with nascent mobile phones; it, too, knows where you live. And then there’s analogue photography too: once cursed, those afflicted appear with weirdly distorted faces on camera film. Ryuji tries it out on Reiko; this is how they know, for sure, that she has days to live (and the dates included on the film are not just there for orientation; they’re essentially an expiry date). The curse creeps into all the technology which forms part and parcel of daily life, making use of it and rendering it conspiratorial, frightening. The idea of ‘viral videos’ did not exist when the film was made, at least not in the sense we would understand it today, though Sadako on TikTok would kill millions in short order; perhaps her curse requires a little more agency than that, at least, and it shouldn’t be forgotten that Reiko dodges her death sentence by – copying the cassette.

Sadako: myth and history

But who, or what is Sadako Yamamura? The child of renowned Oshima psychic Shizuko, she only features in the film as a mute, semi-real presence – we see her clearly only once, as she advances on Ryuji near the film’s close, in one of the most stunning scenes in modern horror – or, as a corpse, floating at the bottom of the ubiquitous well. Sure, the fourth wall had been broken before – weirdly enough, in a lowbrow zombie film called The Video Dead for one, not sure why that springs to mind – but never in such deliberate, unearthly, painful detail. We never see her face, we never hear her, but we know that she can literally scare people to death (the weird, distorted approach she makes was shot backwards at first). Her fingernails are eroded from, we glean, trying to climb out of the well where her mother’s mentor Dr Ikuma pushed her and left her to die; it’s a horrible detail, but one which doesn’t exactly detract from her menace, either. Even in flashback scenes which fill in some of the plot gaps. The reason she is able to do such things is only mooted in the film itself, but Sadako is presented as an amalgam of different mythological figures.

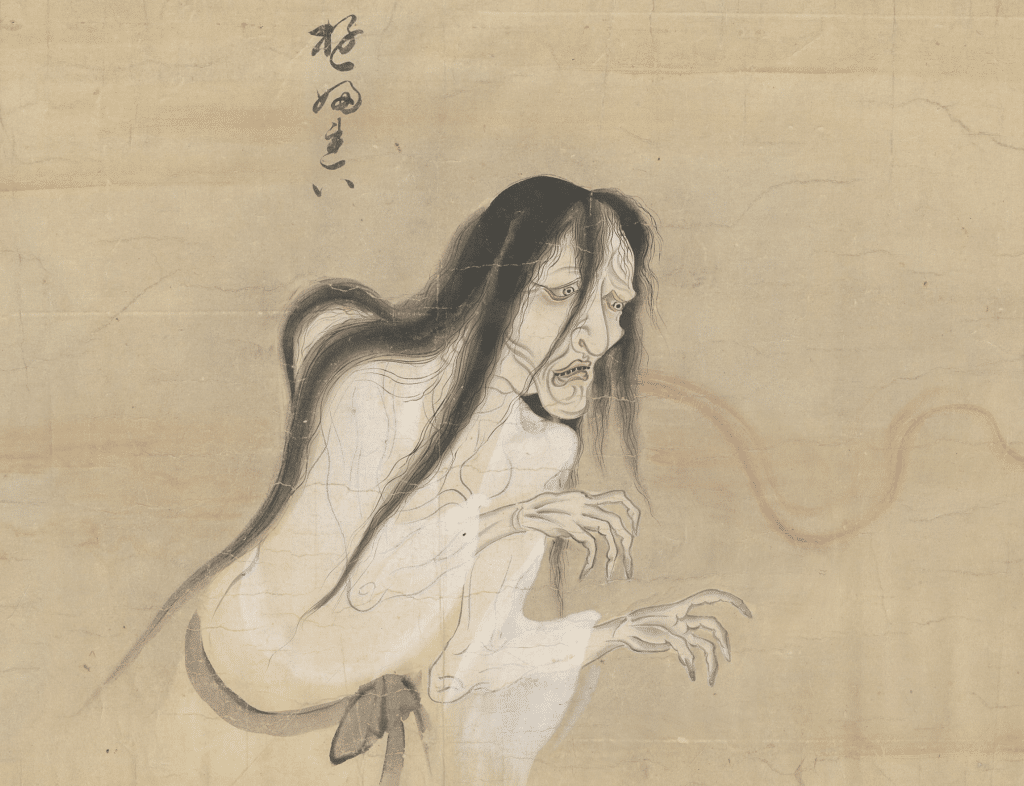

It’s worth pointing out that, in Japanese culture, historically women would not wear their hair loose, unless for funerals, or burials; the significance of Sadako’s long, dishevelled hair may look creepy in its own right, but it is more significant than that, and its death symbolism is clear. It is also associated with some of Japan’s vast array of ghosts and entities, supernatural beings which have some overlap with Western folklore on ghosts, but – due to the country’s unique history, where its Buddhist beliefs have merged and transformed alongside its folklore – often significantly different. Western author Lafcadio Hearn was one of the first scholars to introduce the West to Japan’s ghosts, many of which are perhaps more like our near-lost (or Disneyfied) fairy folklore in the West, neither quite of this world nor quite absent from it, sometimes benign, sometimes malign (Hearn’s writing formed the basis of the movie Kwaidan in the 1960s, providing an early cinematic glimpse at Japanese spectres, particularly in ‘The Black Hair’, which features not only another female rotting corpse with hair loose in a tumbledown ruin, but also some shots which prefigure Ring very closely.) Hearn’s work was well received in Japan as well as in the West: perhaps his tendency to adapt existing folklore for his own dramatic means had some influence on other writers, and filmmakers, who followed his lead.

There are other precedents for Sadako: she most strongly resembles the phenomenon of yūrei, beings broadly analogous with Western ghosts in that they are the spirits of the dead, returned to fulfil some purpose on earth. In the case of the yūrei, or more specifically onryō, being vengeful (usually female) spirits, they will return if they have been the victim of a sudden or violent death (the same idea behind the slightly later film Ju-On, or The Grudge). It’s revealing that the folklore goes that those with least status and power on earth will be the strongest, most formidable onryō if they return. However, the general consensus is that yūrei can escape whatever has drawn them back to the earthly plane, should their relatives perform the appropriate rites for them; this normally enables them to leave that particular life cycle to be reincarnated once again (as per the Buddhist belief system). In Ring, Reiko and Ryuji attempt something which approximates this by seeking out Sadako’s story and attempting to lay her to rest, though they are not family members, just unfortunate strangers drawn into her orbit. However, they are hopeful that this will work, that this will break the curse. It does not; in this respect, Sadako differs from typical yūrei, or perhaps it is also significant that the conflict which ended her life cannot be truly resolved, at least in a way which would end her suffering. With her long, black hair and also the white gown which, in Japan, is also associated with burial, or even seppuku (ritual suicide), she looks every inch the kabuki ghost, spinning out of control in a modern Japan.

Another source of inspiration for Sadako seems to have been the Legend of Okiku, a woman murdered by her samurai master by being thrown down a well. Various versions of the tale have her rising from the well to haunt him. We know that author Koji Suzuki is aware of this legend, as he has Sadako meet Okiku in his manga series, Sadako at the End of the World. And, in another link to the kabuki theatre tradition, which so often took as its basis Japanese folklore and mythology, Ring special effects artist Rie Ino’o deliberately emulated kabuki’s overexaggerated gestures and movements in how Sadako clambers out of the well, and then into Ryuki’s apartment.

But that’s not all. Prior to her murder, we learn through Reiko and Ryuji’s visit to the island that Sadako was of, shall we say, dubious parentage. As much as the married Dr. Ikuma’s relationship with Sadako’s mother was scandalous, there is some suggestion that he was not the girl’s father. So whose child was this? Shizuko’s brother, who still lives on Oshima, intimates that his sister always behaved strangely, spending hours sitting on the shoreline and looking out to sea. He alludes to folkloric beliefs about entities of the sea – as a representative of a fishing family, he is well-versed in this folklore, though ultimately seeing it as potentially harmful, ‘bad luck’. Shizuko’s odd obsession with the sea boded ill; he repeats a saying which suggests that, if you spend too long with the sea, then ‘goblins’ (no doubt a poorly-translated term from Japanese) will come and get you. If this is what happened to Shizuko, then Sadako could be a hybrid, half human and half something else.

Sadako clearly draws on a long and rich series of Japanese traditions, though combined together into something which has the capacity to stand on its own, particularly for Western viewers for whom all of this was very new. Testament to Sadako’s success as an influential figure in modern horror can be seen in how quickly she became a caricature; once you appear in dreck like the Scary Movie franchise, you know you’ve made it, even getting across the divide to the true quick-buck hucksters. There are a lot of less cynical Sadako-a-likes out there too, both in similar J-horrors of the era (and many, many since), and in the likes of Cabin in the Woods, in which a Sadako-looking figure appears amongst the ranks of seminal movie monsters. This to me feels like a far more complimentary tribute to Sadako, but imitation alone is a form of flattery.

Legacy and final words

As well as Ring’s sterling work creating something terrifying out of a number of pre-existing elements, you can perhaps chart some of its other features in other, earlier films. The Woman in Black – a very Western ghost story, but one based on a fractured family and a woman’s particular, inescapable vengeance – often comes to mind for me, if only in the ways that ‘solving’ the mystery is just as ineffectual in ridding the curse. The M. R. James story ‘Casting The Runes’ has had a significant impact on horror, most famously in Night of the Demon (1957), in which a curse is passed to an unlucky recipient (though with a quicker turnover in the film of just three days). The demon itself does appear in the film – some might say it would be stronger without – and indeed later film and TV versions play rather more coy with the big reveal, thus having more in common with Sadako’s screen time in that respect.

There have been a number of diminishing-returns sequels since Ring first surfaced, each adding additional context and information to the backstory which, honestly, feels unnecessary but, given the huge success of the original film (Japan’s highest-grossing horror film of all time) inevitable. I’m honestly avoiding too much of a mention of the American remake, which got it wrong, wrong, wrong, even making the new viral video clip somehow humorous, which takes some doing, given the base material. But, in its way, it stands as a useful reminder that people should just watch films with subtitles, not wait for a half-arsed version to appear which usually obliterates all the best elements of the original; J-horrors recast for American audiences have not worked particularly well.

There have been other precedents for the whole ‘video as dangerous artefact’ shtick, namely Evil Dead Trap (1988) which has another female journalist investigating a video tape which purports to show a sadistic murder – thus overlapping with the whole ‘snuff’ mythology, still rumbling along at that time. There’s something of Ring in Sion Sono’s 2001 film Suicide Club which, although not having a supernatural storyline, does feature a mysterious viral message that triggers a number of dramatic suicides (this time, the call goes out via a creepy webpage – analogue is no more it seems, just a couple of years later). And, in more recent years, time-sensitive jinxes have appeared in such disparate supernatural horrors as It Follows and Drag Me To Hell, each giving the victims a very limited window of opportunity – and some miserable choices – in order to attempt to stave off the lurking evil which is imminently coming for them…

Ring is a horror film which not only revolutionised cinema in the West as well as in its native Japan, opening up a whole new world of horror to us, but is also a film which stands up incredibly well, after twenty-five years and I’m sure long beyond that, too. Rewatching the film for the purposes of writing this article stirred up the same old feelings of unease, chiefly over the video clip itself, then of course from that final evidence that Sadako’s curse was not over. That’s of massive credit to the film, given how many hundreds of films have failed to make that mark – either on me, or in general – in the intervening years. If we’ve come to a point where the longhaired ghosts are just a little too ubiquitous, then it’s worth remembering that they became so numerous because Ring was so worthy of emulation. Nothing should, nor could, take that away from this brilliant piece of horror.