It’s a little curious, speaking from a personal perspective, that Netflix’s Squid Game has turned into such a break-out success. This is not to claim it’s anything other than great TV – in many respects, it is – but, given the sheer amount of new series routinely arriving on the streaming service, for a Korean language drama to make it to the top of the pile is rather unusual. Certainly, the ways in which we watch TV and films has changed; it was on the cards for some time before a succession of lockdowns closed the cinemas and closed off one of the traditional viewing options, but Covid led to a boom which is only just starting to slow. Netflix is now commonplace, and its reach and influence not only bring in television from around the world, but have the clout to promote it. And so, Squid Game – an idea ten years in the making – has finally reached its global market, with the true mark of success – media terror of copycat games – now hitting the news.

But why has it grabbed people’s imaginations in this way? Many of the issues which drive people into the games come from what seems a very Korea-specific set of problems. Of course, debt stalks people in all parts of the world, and the gap between richest and poorest continues to widen across developed countries, but in many ways the Korea of the first couple of episodes – a Korea riven with poverty, mass-occupancy hostels, endemic zero hours employment, all-too-easy loans, crippling personal debt, rocketing property prices in the country’s cities – is out there as a particularly serious example of what debt can do in a toxic slew of high-concentration population, a deep culture of shame and a country where debt exceeds GDP by 5%, making it all but impossible to clear what you owe. Gi-hun’s desperate spree in the first episode, betting money, gambling for a gift, stealing and committing fraud – is bleak, but plausible. Only a quick fix can set him free.

The same is true for his peers – a disparate bunch, each with their own motivations, but each vulnerable through poverty, exacerbated by debt and fear. Where the family at the heart of Parasite (2019) find a carefully-constructed ruse to improve their fortunes, the players in Squid Game find themselves instead seduced into a bizarre competition, where children’s games are given a deadly edge, making the incentive to win as much about survival as profit. However, this is not explanation enough on its own for the show’s success, and nor – quite – is the snowball effect which hits once a critical number of people begin to enthuse about something. Nor does it explain away some of the show’s weaker moments. Parasite is, for many people, probably one of the sole points of comparison for Squid Game and in many respects, it is a useful one to think about as it, too, tackles South Korea’s significant class divide. For a lot of genre film fans, though, other existing Korean (and other Far Eastern) films may spring to mind, even if these belong more to the horror tradition: the slow-burn cruelty, the artistic gore, the ways in which human behaviour is put under unique pressure, many of the most notable movies which have tackled these over the past twenty years have emerged from an explosion in Eastern Asian cinema, from the fights to the death of Battle Royale (2000) to the fantastical class divisions of Snowpiercer (2013) and to As The Gods Will (2014). These films share some commonality with the likes of the Saw franchise, The Hunger Games, and similar; horror and sci-fi love a fatal contest. So what does Squid Game do which distinguishes itself from these?

The rest of this article discusses the series as a whole and as such contains spoilers.

‘Free will’ and the games

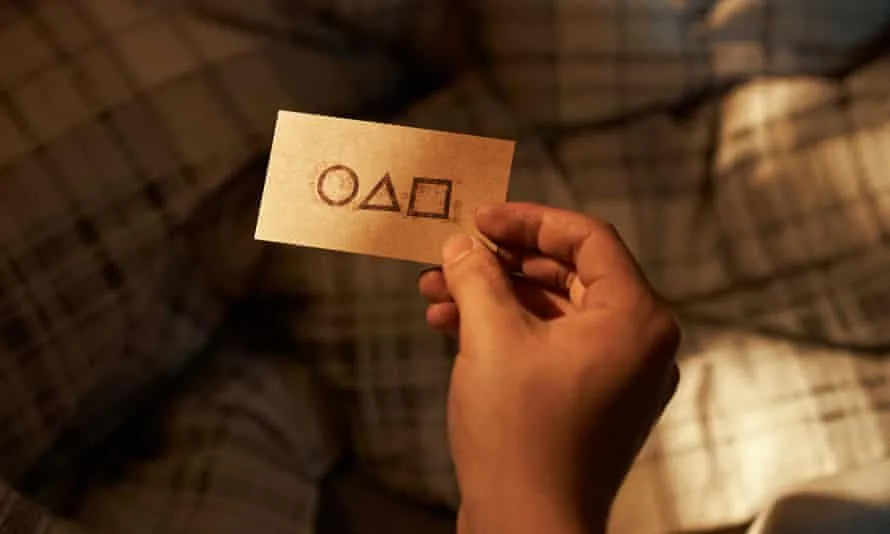

One of the things which the series does really well is to explore the idea of personal choice. When Gi-hun is first approached by the mysterious promoter, it is at a time when he has hit his lowest ebb. Long since made redundant from his job, eking out a living as a driver, living with his elderly mother, estranged from the daughter who is about to be taken to the other side of the world – it seems that he has few options left in his life, and has developed a taste for gambling. He can’t resist the promoter’s too-good-to-be-true patter, and takes the bait, playing his first game, later phoning the number given to him and gaining access to the contest. But the brutality of the first game (a skit on what a lot of us in the UK would probably call Grandmother’s Footsteps, only without the artillery) sickens those who make it across the line. They discuss: what should they do?

By the narrowest of margins, they opt out, and, in one of the series’ first real surprises, the organisers allow them. They are put safely back in mainland Korea, where they are free to go about their lives again. The lesson which the show puts across isn’t an ornate one, but it’s important, because it invites us to wonder – could they, really, resist the lure of the cash to be won in the game? Are they free at all?

Gi-hun is immediately back to where he started, a seeming failure by most measures: still dependent on his ailing parent, making occasional money, blowing most of it. His neighbour and co-entrant, golden boy Sang-woo, may have a great education and a wardrobe full of sharp suits, but he is in no better state – something which is later pointed out to him by a desperate Gi-hun. His phone buzzes with threatening, cajoling messages demanding the money he owes. Elsewhere, Pakistani immigrant Ali has created a dangerous situation for his wife and infant son; the as-yet nameless elderly player, who bumps into Gi-hun by chance outside, is still left wondering if he could have progressed in the game, won the money. As their situations as free citizens come home to them, they feel less and less free. So they decide they want to pursue the tournament after all, and though they have to fight to find their way back inside, this time it seems that it’s set in place, with an expectation that everyone present now plays on, as required; at least, it’s not until close to the series ending that the suggestion of opting out is mentioned again. Whilst it’s less clear as the tournament progresses and the staff have less to say which doesn’t relate to game rules, it seems as though it would be highly difficult to quit a second time; for the players, their options have now run out, in a literal sense. Were the controllers of the game always aware that this would happen? Their certainty that they would get their players back eventually seems reasonable. Again, it’s a subtle point, but the inescapability of the game could stand in for the wider point about the inescapability of debt. It also, to an extent, underlines the ferocity of the competition: the element of choice is called into question, but the end result is kin to any number of brutal, often ‘reality TV’ themed battles. It’s an opt-in torment, at least at first.

‘Gganbu’

If the series does seek to dramatise the desperation felt by people mired in money worries, then it’s significant that you get such a range of players from all walks of life (although only a small number of these are characterised in any depth; it’s still not really clear what Mi-Nyeoh’s deal is, other than a frantic need to form alliances which dissipates just as unexpectedly). But we get white collar, blue collar, criminal underclass, elderly, immigrant and North Korean players, who really are left to their own devices because for the most part, the games are unpredictable. If there is inequality on the outside, then that’s replaced by a different kind of inequality on the inside, because each game requires different skills and strengths. That’s not to say the process isn’t flawed, however, during the period where one of the players gets – and shares – a distinct, if short-lived advantage. For the most part, attempts to predict what game will be played come to nothing, or worse, lead to a disastrous misjudgement.

The earliest games are brutal because they accrue vast numbers of casualties; as the vast majority of players remain nameless, the effect is cumulative and can feel overwhelming, but it’s probably not especially shocking for fans of horror, or other related genres come to that. But the most effective emotional kick is yet to come – an example of perfect timing by the series team.

This episode of Squid Game comes just after we have started to develop a liking for some of our characters and their attempts to work together, even if we might be able to predict the glorious unravelling of Sang-woo, already acting like a hawk amongst the doves. As the characters have already successfully worked together, when they are asked to pair up, they do so expecting to have to represent a united front and the initial clamour is from people trying to find a ‘strong’ pairing, expecting a physical challenge of some kind (which itself leads to a rejection of all the women and older players present; equality quickly dissipates when there’s a potential strength or dexterity contest in the offing). But the game itself is – marbles. This leads to one of the show’s greatest about-face moments, when it turns out that they will have to compete against their partner, not work with them. Titling the show ‘Gganbu’ – which translates roughly to ‘buddies’ or ‘partners’ – is another of the show’s very strong moments, a dramatic irony as the nature of the term is unpicked. Excuse the reference but this is an episode which could have been penned by Arthur Miller – its minute focus on people breaking apart, on nostalgia becoming something toxic in the moment when characters need anything but immersion in nostalgia.

Gi-hun is at first sad and reluctant to partner with the as-yet nameless, elderly man whose illness seems to affect his concentration, as well as leaving him especially vulnerable. Gi-hun is aware, then, that were this a game of physical prowess, he is a dead man, but he also fears that a no-partner situation would make him a dead man too. The trick up the sleeve is that marbles relies on skills of luck and bluff alone. This, when it becomes clear, spreads through the rest of the players like a wave, particularly where people have paired up with someone they know and like, or love. There is a husband and wife team in the game, for instance, and it is understood that only one of any pair will progress to the next game – something alluded to only later, when the entire weight of the episode has already seemingly been felt.

We see two distinct progressions here in the lead characters of Gi-hun and Sang-woo, and this is probably the high point of their character arcs, where everything which follows feels like a direct progression from the events of the marbles game, how they decided to act on that occasion and how they feel about what follows. Does the show’s ending undermine that? Yes, to an extent it does, but Gganbu is nonetheless the show highlight, and still works as a solid foundation, even given the writing decisions which bring the series to a close.

Childhood friendships?

The series starts out following Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae, usually a straightforward hero). And, first impressions of him are far from positive, even whilst slowly taking on board why he behaves as he does. He is childish, erratic and unlikeable, resorting to teenage-like fits of rage and frustration when he is challenged on anything; he steals, he cajoles and – even where the first episode seems to be showing him catching a break – his ineptitude quickly turns his good luck around. It takes time before his struggles with money and the newsworthy way he left his old job at a vehicle factory are revealed. If we feel any real sympathy with him at this stage, it is in his loving, but problematic relationship with his ten year old daughter, whose successful, eminently reasonable stepdad wants her inept biological father out of the way. Even then, though, he messes things up, acts ridiculously. He could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the unreconstructed Dae-Su Oh from Oldboy (2003) and get along with him perfectly well. Whilst it’s clear that Gi-hun’s character will change, this happens in unexpected ways.

It takes time – and exposure to the tournament – before Gi-hun becomes to blossom into a good-hearted man, and much of this comes through his contact with the elderly player, eventually revealed to be called Il-nam, or Player 001. Perhaps they share a father-son dynamic, as the older man speaks a little about his son’s childhood and Gi-hun’s own father is no longer around, but Gi-hun first takes it upon himself to treat Player 001 respectfully, showing deference to him and trying to protect him from the mob rule which quickly takes hold. This protective element in his behaviour soon comes to encompass other players, even the ‘pickpocket’, as he once knew her: defector Sae-Byeok (Jung Hoyeon). It also creates his greatest dilemmas, contributing directly to his failing moral conscience in ‘Gganbu’.

Gi-hun eventually has to confront his old friend and on-paper success story, Sang-woo, and whilst the camera spends slightly less time on the latter’s own journey through the game, they have developed differently. Sang-woo is terrified at the beginning, meek and in every way a man who is not worldly, but he learns fast. This to an extent paints him as a straightforward villain, however, letting him step in for the cartoonish, but no less watchable gangster, Player 101: Sang-woo even emulates his deadly behaviour, minutes afterwards. If this transformation is a little hard to take, then it is given a little more depth back by the finale, where it’s revealed that Sang-woo is still human, and is regretful. It’s as if each of the childhood friends take a different route to their final conflict, but remember enough about themselves to be equally humane, in the midst of it all.

Criticisms: The VIPS

This site won’t be the first to comment on the presence of the ‘very special guests’ at the games, and it won’t be the last, but frankly, the VIPs element of the plot, as we see it, is a misfire. Much of the criticism so far has been around their language and speech, something the actors have already addressed, with some indignation. But it’s a reasonable thing to criticise. The presence of English language sequences in a Korean, or any other non-English language production always has the potential to go awry wherever you have actors who don’t know what they are saying, or a production team who don’t know what they’re saying, or both. It breaks up the plausibility very quickly, and it just sounds…bad. It’s clear that lines have been learned, rather than someone making an organic attempt to converse. However, that’s not my main issue with these characters.

They contribute almost nothing to Squid Game, because it would have been more than enough to believe that South Korea had enough of its own unprincipled rich people getting off on the suffering of their countrymen. As discussed earlier, Squid Game takes for its basis an acutely Korean problem. It is set in Korea, it stars Korean actors and it is a Korean language production; is it so hard to believe that Korea’s rich wouldn’t be in on this universe, without a supporting cast of the almost obligatory fat, unpleasant, unfeeling Europeans and Americans? If their inclusion was an attempt to suggest that ‘the games’ are a global phenomenon of some kind – a sort of Hostel-style in-group, like Elite Hunting – then the VIPs are just not strongly drawn enough, and barely present enough to successfully add this layer to the plot. They are simply there, deliver a few hesitant lines from a chaise longue or two, and then they’re gone.

It would be good to think we’re past having to bung in a couple of Americans etc. to properly have a chance in a global market, and the fact that Squid Game has done so well despite the VIPs would support that. There’s a certain cliché aspect to the ‘evil pervert foreigners’, too, given that the games are usually perfectly well organised from inside Korea, and evil pervert foreigners have had plenty of franchises of their own. Unfortunately, the VIPs are a fairly unnecessary bit of window-dressing from a series which was doing just fine without them, and returns to form when it moves past them.

Criticisms: the ending…

Waiting for a series finale is a toughie if it’s one you’ve enjoyed, and the way in which Squid Game wraps up isn’t perfect. There was always going to be a lot riding on this one, and there are some fundamental issues.

Whilst seeing our main guy win after a final redemptive moment feels like a relief, the series then disrupts expectations. That’s no bad thing, and any expectations of Gi-hun going around simply fulfilling the wishes of his old teammates are dashed by the decision to represent him as a broken man, ill-equipped to go on, with a timeframe spanning another year. This is, though, a reasonable addition, because the money hasn’t been an instant fix; the big problems of life before are not only still in Gi-hun’s life, but they’ve worsened. The episode lulls a little around this time regardless, and it isn’t really clear where we are going next.

Then, how things move forward is divisive, and sadly it’s divisive because it undercuts some of the effective emotional development which came before, notably in ‘Gganbu’. That episode required some real emotional work, so plucking a key character from that and revealing them to be a different character entirely seems more about revealing the trick shot which kept them around, rather than really building anything significant out of it. In fact, by stripping the meaning out of some of the care and consideration which Gi-hun showed at that point, it jeopardises that element of his development, and I’d always prefer consistent writing to the phenomenon of ‘Easter eggs’, which is something which screenwriters seem hard-pressed to leave alone.

The series also seems to feel under pressure to account for the bleak cruelty of it all, and its method for bringing it all together relies on a blend of ennui and nostalgia, which Sang-woo alludes to far more effectively in one line when he realises aloud that their childhood innocence is gone forever. This is a theme throughout – the arenas are a blend between Disneyland and The Thunderdome – but it unfolds more in the background, an intriguing feature of the tournament which blends horror with childhood throwbacks, a creepy aesthetic choice. It’s more effective left there, frankly, as something to think about but not get a clear answer; the final episode decides it’s time to talk us through a significant part of this, and immediately lays itself open to seeming thinly sentimental. It’s just hard to buy the rationale we get for this character turnaround, and the add-on about ‘people not being kind anymore’ feels unnecessary. We’ve seen what people can do, and we’ve seen them being kind too, at length; this is what has redeemed Gi-hun.

Could it be that all of this is simply to set up a Series 2? Whilst at the time of writing there are no clear indications that a S2 will be happening, some of the issues in the end episode could certainly be cleared up by further address. With the greatest of respect to the series, however, this isn’t the most satisfying way to conclude S1. Gi-hun seems to have work ahead of him; there is potential there for a completely different character arc, and perhaps this is on its way, though it’s a shame that this has come at some cost to the superb writing in what we have already.

Squid Game is, nonetheless, worthy of the attention which has been paid to it. It is aesthetically strong, with moments of absolutely superb writing and acting, fantastic use of spectacle and gripping storylines. In its struggle to finish its story, it perhaps goes astray, and it is unfortunate that some of these moments detract from what has come before. However, it has plenty to recommend it, and if this is the first experience of Korean TV/film for many people, then it’s a solid one which could itself lead on to good things.