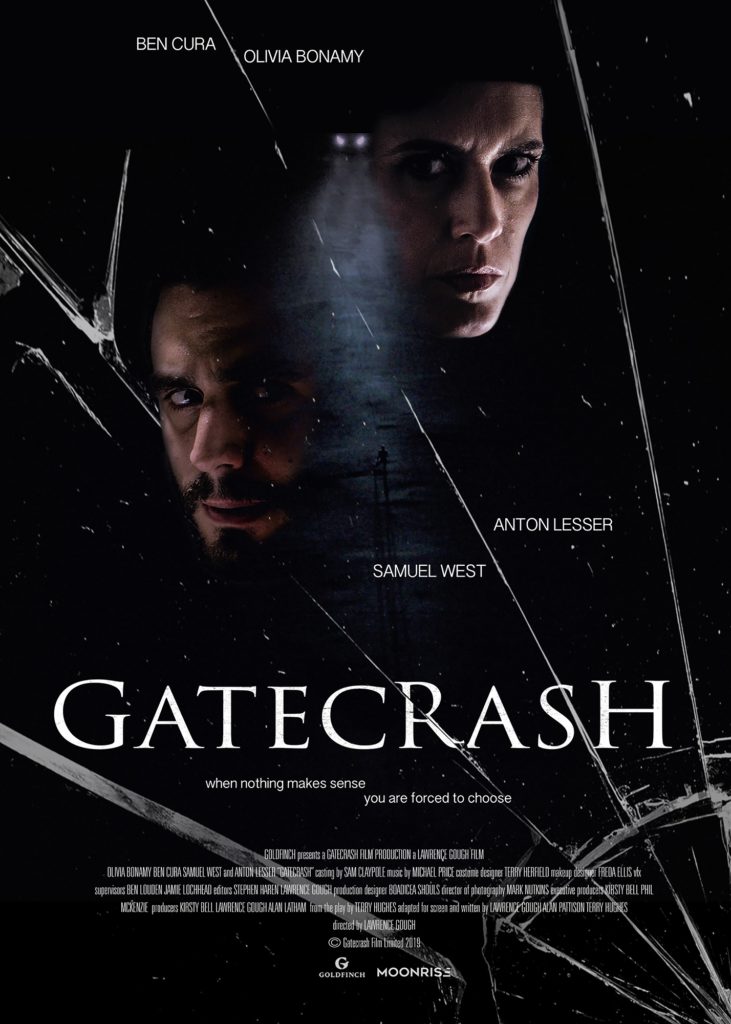

Gatecrash (2020) has an interesting pedigree; based on a play, and directed by Lawrence Gough – who has spent far more of his time working on television than cinema over the past decade – it’s a film which contains aspects of both the stage and the small screen. That being said, there are some similarities with Gough’s earlier film, Salvage (2009): remember Salvage? Gatecrash is by far the superior project, showing the benefits of directorial experience over the intervening decade or so; it’s an often jarring, discomfiting film which, like Salvage, unfolds almost entirely in a narrow domestic setting with just a handful of characters. Unfolding some neat tricks along the way, it is able to overcome its few odd omissions or oversights.

The film begins as a car arrives, late at night, back to a rather plush house and grounds. The driver, Steve (Ben Cura) and his partner Nicole are already in conflict because it seems that their vehicle has been involved in a hit and run incident and, in a panic, they have headed straight for home. Recriminations soon begin to fly: Steve had been drinking, the man they struck came out of nowhere, and – most damning – Nicole suggests that it was no accident, that Steve drove into the pedestrian deliberately. Seems plausible, to be honest; he is presented as a Bad Man pretty early on. The initial whirlwind subsides as they discuss what to do, but when the house landline is rung by Steve’s missing mobile phone, it’s clear more is going on here. Oh, and then there’s the small issue of another car pulling up on the drive…

The film starts strong, with Gough clearly knowing how to show tension: the quick edits, the way in which things open mid-conversation and the close, claustrophobic focus all give a sense of things being blurry, disjointed – and veering ever towards hostile. Nicole and Steve are either within inches of one another, or shown momentarily alone in different areas of the house – there’s no sense of a united front here, something which grows increasingly important. If anything, the successful disorientation of the first fifteen minutes or so works against characterisation initially, but them’s the breaks with this kind of approach. Some of the dialogue, similarly, feels a little thin at first – sacrificing the plausible to amplify the odd – but, when Gatecrash settles into a pace and a mode, or perhaps at the point when I settled into the film’s pace and mode, it does hold the interest very well.

Nicole rises to the fore as the film moves on, and the use of long, continuous takes as she runs from room to room helps to keep the audience on her level; our viewpoints emulate hers, and it creates empathy. She’s not your usual ‘final girl’ sort of character, thankfully, but when the film makes a sizable shift and shifts forward in time (like a play, the film falls broadly into two ‘acts’) it’s Nicole’s fate we are engaged by, and Olivia Bonamy does well with her role, balancing a kind of strained, terrorised civility with moments of plausible horror; Nicole is a woman clearly shattered by her treatment. Also, Bonamy may be French, but she gets the required British ‘squirm’ very well; this film, in several ways, represents a peculiarly British type of home invasion. Gatecrash manages its latter shifts in direction nicely, albeit it generates plenty of questions on how – or if – this situation could ever be resolved. And, whilst it’s a shame that one actor disappears, it’s equally a real treat when another appears.

Much more about the threat of violence and exposure than it is overtly violent, Gatecrash is a decent, well-wrought film which, although it doesn’t answer every question you may have, does more than enough to stay engaging across its ninety minutes. It certainly moves away from the predictable, and for that alone it deserves credit in a genre which has tried every trick in the book. Nice to have you back, Mr. Gough.

Gatecrash will be available on digital download 22nd February.