It was with no mean amount of anticipation that I went in to Robert Eggers’ newest film; his last film – and his first ever feature – The Witch (2015) blended just enough ambiguity with its supernatural content, leading to a film which kept its mysteries without sacrificing its scares, but perhaps most of all, it successfully crafted a tale of the profound impact of isolation. It seems this is a theme Eggers wanted to explore further, so The Lighthouse has an even smaller cast, and the complete isolation of two men who – shall we say – would not ordinarily be friends. However, for me, the interplay between possible supernaturalism and isolation simply is not sustained here with the same level of success as in the earlier film. Atmospheric it may be, but The Lighthouse is in other key respects very, very dull indeed.

The premise is simple enough: on a remote island somewhere off the wind-battered New England coast, two men have taken on the role of tending the lighthouse there. It’ll be a four-week stint, then someone will be along to relieve them. The older of the two men, Tom Wake (whose name I heard as ‘Wick’, and thought was a bit of nominative determinism) is a grizzled old hand at this, and he makes it very clear to his new second-in-command that tending the light itself is his job. Everything else, it seems, is to be done by the younger man, who eventually introduces himself as Ephraim Winslow. It’s back-breaking and thankless work, and there’s little respite: the only thing to do in the evenings is huddle in the dim lamplight and, eventually, share a few stories.

But there’s something odd about this place: Wake reveals that his last helper went mad, and whatever is on Winslow’s mind seems to be troubling him, too: his dreams are increasingly traumatic, and he soon begins to lose his sense of time. Wake comes across as a practical man used to the life, but his determination to stop Winslow from having anything to do with the lamp – as well as his demented fixation with the power of the light – suggests that there’s a force or a presence involved with it somehow. Winslow’s curiosity is given little credence, and as the two men continue to co-exist, tensions develop between them. Winslow reveals that he isn’t, in fact, called Winslow – his name is Thomas Howard. Lots and lots and lots of rum (I assume) gets consumed. Many suppers are eaten. A seagull gets battered to death, possibly leading to an awful lot of bad (or worse) luck. And eventually, the confinement begins to get to Howard far more appreciably, driving him to desperate, violent behaviour.

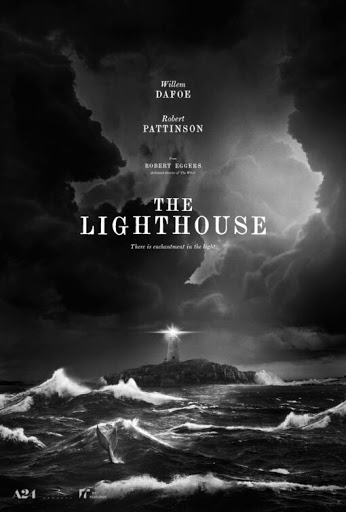

Granted, there are elements here to admire. The choice of black and white certainly lends the film a grim sort of gravitas, and the tempestuous seas genuinely look impressive on screen. The continuous booming of the foghorn lends an air of menace which suits the content well. Inspired, also, is the casting: Willem Dafoe does a great deal with what he is given as Tom Wake, and Robert Pattinson is barely recognisable from his days as a harmless but feckless Twilight pin-up boy. They plausibly enact two men getting heartsick of one another, doubting one another and finally exploding into anger; they each play very physical roles, growing steadily more ingrained with filth and soaked by the perpetual rain. The Lighthouse is a very sensory film indeed.

The thing is, in its unwavering pursuit of atmospherics, narrative coherence and structure have been almost totally sacrificed. Whilst the horrors of witchcraft in The Witch could conceivably have been all in Thomasin’s mind, her family’s remote lives and hardships taking its eventual toll on her, it never felt like a cop-out for all that, and works just as well as a film whose witchcraft is real. The film felt as though it had a shape to it, too, whereas that is almost totally lacking in The Lighthouse which, at one hour fifty minutes, desperately needs some sort of pay-off to reward audience patience (several people walked out of my screening, I’m sure beaten back by the relentless nothingness of it all). In common with The Witch, The Lighthouse hints at some supernatural goings-on, but removes these even further from plausibility by making it all possibly ‘just a dream’, even suggesting in the script that it could all be a figment of the imagination of a young man trying to run from his own guilt. And there is no exposition at all, just a couple of hints of something weird out there, enough time for a mermaid sex scene (I guess that’s ONE burning question the film answers) and some deeply suspect seagulls. I liked some of the allusions to sailor lore, and who doesn’t love a shanty? But with so much screen time dedicated to watching two men steadily getting sloshed, The Lighthouse is less a brooding study of madness and more a Lovecraftian piss up. Moments of humour don’t really work, either: the farting, wanking and brimming bedpans jostle for position with long monologues about how bad the other person smells.

So, sadly, whilst I could marvel at the physical hardships undertaken by the two leads, and whilst Eggers has done sterling work displaying the ocean as a malign entity in its own right, this is a jagged, indulgent film which says very little. It is likely to be a very divisive offering, with its fans adoring its psychological horror and its detractors feeling almost completely detached from its psychology. Perhaps the ability to split viewers so cleanly is an achievement in itself, and if this was ever the aim then – mission accomplished, but ultimately there is just too little of substance here and the ends do not justify the means.