It’s hard to believe that two decades of the new millennium have already passed. It seems like only yesterday that we were complaining about ticket prices for Millennium Eve, whilst simultaneously fearing a computer glitch which would potentially mean the end of the world as we know it. Well, it didn’t quite happen that way – but it’s fair to say that we live ‘in interesting times’ these days, hyper-connected to one another whilst also experiencing epidemic levels of anxiety and loneliness, riven by social, cultural and moral uncertainties and often living very precariously, even whilst being aware that, comparatively speaking, we’re often healthier and wealthier than our predecessors. Little wonder, then, that horror cinema has survived and thrived in the 21st Century so far. If we accept that horror offers up a distorting mirror to the society which generates it, then there’s ample material there, not to mention more and more ingenious ways – at least ostensibly – to reflect our fears back to us, in terms of what can be done on-screen. Horror is alive and well, a constant in many regards, but also something which is morphing and shifting as life morphs and shifts for us all. Perhaps it’s more vital than ever. However, over the past two decades, it’s become more and more common to see horror cinema represented as being something else entirely. Having castigated the genre as being low-brow and tawdry, occasional viewers have had a tendency to feel rather surprised when a horror film turns out to be rather good. So they do what anyone would do – they decide what they’ve seen must belong to a different sub-genre altogether.

The ‘Post-Horror’ Fallacy

Seeing horror dismissed outright by many critics and viewers as beneath contempt has been a bugbear for its fans for many years longer than twenty, but the one thing which seems to irritate us more is seeing horror re-named as something else, simply because if it’s good, then it can’t be horror. It’s a little like calling the stuff you like ‘erotica’ and the rest ‘porn’ – it’s justifying ones mores to oneself. Horror is rife with it. This cognitive dissonance does a great disservice to the filmmakers and audiences who already get the point that horror can be clever and nuanced, and it makes the commentator making their half-baked distinctions look woefully misinformed, even deliberately disingenuous. I mean, if it’s Kiss bassist Gene Simmons talking about how HIS films are going to be ‘elevated horror’ rather than, y’know, horror, then we can probably safely assume it’s a marketing strategy as much as a legitimate declaration. But when you get a mainstream newspaper like The Guardian running a feature on ‘post-horror’, then you have to wonder what’s going on. The distinction is still not clear to me, as most of the films mentioned as ‘post-horror’ in the article are – you’ve guessed it – horror, in all its wonderful variety. As Nia commented, in one of the most popular pieces we’ve ever run, “the only thing that is too rigid about horror is the persistent and false belief from some that it is not good enough and not profound enough; and, somehow, not broad enough to encompass all that it does.”

The compulsion to disparage seems to lead directly to the compulsion to re-divide and re-name; it’s entirely unnecessary, wrongheaded, and exasperating. (The same goes for calling horror ‘highbrow horror‘, by the way. Same applies. I could go on and on.) What’s especially galling, though, is when a horror director whose work has been embraced by fans, their profile raised accordingly, decides to shrug off the association with the genre when the going looks good. This simply entrenches the old attitude that horror is simply a step up to better things, which surely makes it harder to argue that the genre is inherently satisfying in and of itself. So, we will get more ludicrous attempts to call the genre more palatable things, we will almost certainly get more directors calling their horror movies ‘social thrillers’ or ‘dark fantasies’, and horror fans will always find it galling. Sadly, in the days of viral articles and accessible outrage, we’ll continue to see all of it, too. But what of the films themselves? What has been significant about the horror cinema of the new millennium so far?

Let’s start on a heart-warming one.

‘Torture Porn’ and the Rise of Ordeal Cinema

Yep, having just defended horror for its expansiveness, and argued against its detractors, we come to a sub-genre which has very definitely divided audiences, right down to the choice of term ‘torture porn’, as coined. Ask different people and you will get different ideas about the derivation of the term: some say that it refers to an unsavoury sexualisation of on-screen violence, whereas others say it’s to do with the unflinching focus on physical trauma, in the same way that the camera refuses to look away from sex acts in pornography. Perhaps though the point here really is – where did this divisive type of film come from, and why did it escalate its graphic cruelty in the first decade of this century? Even for many diehard horror fans, It quickly felt like an intrusive addition to the genre. Sure, people had been put through excruciating ordeals in horror before, and the 1970s had their fair share of cruelty for cruelty’s sake, but the sheer glut of torture and torment after Saw (2004) seemed to open the floodgates, something which feels pretty significant in hindsight.

I still believe that there are examples of this kind of ordeal cinema which are well-paced and delivered well enough to shine through, but the number of Saw-clones and tied-to-chair horror films quickly made me feel inundated and a little bored, and it’s not nice to feel completely alienated from someone’s on-screen suffering. Familiarity breeds contempt, here as anywhere. But the formulaic nature was so quick to establish itself: unwitting outsiders (or unwitting hosts) find themselves menaced with household tools, always tied to something, always maimed in slow-mo. Wolf Creek (2005) severed a girl’s spine and turned her into a ‘head on a stick’ so she couldn’t run away; Hostel (2005) saw a jaded man blowtorch a woman’s eye because he was utterly bored with his life and wanted something to ‘remember’; in the absolute nadir of the subgenre for me, Neighbor (2009) has a nameless woman torture a group of guys – subversive! – for no particular reason, right down to a penis torture scene, which was inevitably cut by the BBFC.

I have read some interesting commentary on how the genus of this kind of cinema seems to be our cultural exposure to scenes of torture via revelations coming out of Guantanamo Bay post-9/11, and I do think there’s something to this: there’s that distorting mirror again, with real-life footage of people manacled and their faces covered bleeding into horror narratives, as we collectively tried to make sense of a world irrevocably changed and more overtly violent, threatening and divided than it had been in decades. However, I think there’s a kind of grim pragmatism to the proliferation of ordeal cinema, too. Firstly, it isn’t riveted to stellar storytelling. The better ones have characterisation and (some) direction, of course, but ultimately you could potentially get a film green-lit on its boasts of unparalleled violence, not its narrative arc. It was a popular, affordable ingredient. With decent make-up effects and lighting, the gore could look plausible, the action could unfold on a limited budget and the end result could potentially appeal to a new wave of audiences who prided themselves on getting through it at all. No film is ever made in a vacuum, either – so as one ordeal film did well, another would quickly pop up. It now all seems like a torrid, but fairly short-lived horror trend, with the potential for an easy, lucrative horror spreading like wildfire through the ‘horror scene’.

Some of the most monstrously cruel films did not originate from the US, however, and the early years of the decade saw the rise of what is now dubbed ‘the new French extremity’, as French filmmakers took advantage of new opportunities to get films funded and made. That said, their cruelty is often of a rather different, more nuanced variety overall, even whilst not scrimping on the gratuity or the bodily close-ups. Mental breakdown segues into bodily breakdown more readily in this kind of French (or sometimes Belgian) cinema, with Dans Ma Peau perhaps my favourite example of a bloody, but engaging and deeply sad study of one woman’s withdrawal from the pressures of modern life. However, the ultimate meld between existential angst and torture has to be Pascal Laugier’s film Martyrs (2008), a film where torture is ostensibly not undertaken out of mere cruelty, but because pain is deemed to be a gateway to a higher understanding. For me, this is where the wave rolled back for torture cinema: having gone to that extreme, further instalments of that level of protracted torment felt rather empty, newly needless in a way which marked the beginning of the end.

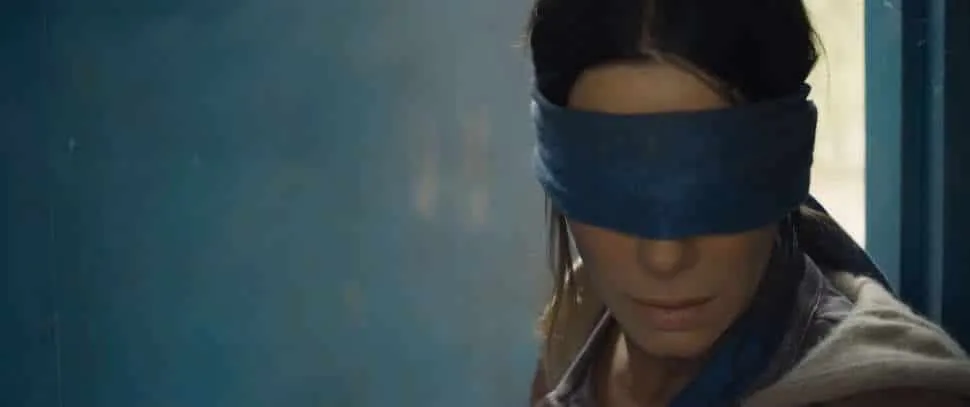

On-screen torment, whilst still protracted in its own ways, now seems to have morphed into sensory deprivation, rather than sensory overload in the form of physical agony. It is still cinema which riffs on helplessness, often re-introducing literal monsters into the mix (the monsters in ordeal cinema were almost invariably human), but its anxiety is linked to sightlessness, or soundlessness – an inability to see or speak. Some examples include Don’t Breathe (2016), A Quiet Place (2018) and Bird Box (2018) – perhaps films too few in number to really declare a new sub-genre now exists, but an interesting indication of where on-screen ordeals could be going. People seem to be losing the taste for torture and looking elsewhere.

Horror Cinema and its Millennial Monsters

The films discussed so far almost all have people as their monsters, but the more literally monstrous – in the sense of inhuman or supernatural in some sense – definitely hasn’t gone away. In fact, the earliest years of the new millennium seemed to generate a new wave of zombie horror, although the zombies themselves were often barely recognisable from George Romero’s shambling, but relentless hordes across his initial trilogy of the 60s, 70s and 80s respectively. At the beginning of the Noughties, zombies even seemed more inclined to run than to shamble, to the consternation of many fans; high-profile remakes of Romero’s work, beginning with Dawn of the Dead (2004) and followed by a new version of Day of the Dead (2008) opted for bigger, bloodier outbreaks, where not only was the threat of contagion present and correct, but these zombies seemed to be in a weird state of enraged athleticism, which brings its own terrors, even if you don’t much like this development. The same is true of ‘is it or isn’t it a zombie film’ 28 Days Later (2002), a film which at least carries enough of the hallmarks of a zombie film for it to feel right to mention here; the same societal breakdown, the same desperate survivors, the same masses of no-longer-humans who want to catch you and turn you into ‘them’. That it was all blamed on ‘rage’ seems very fitting, all things considered. Call it a zeitgeist film, perhaps.

Romero himself was back directing in 2005, with a film which picked up where his Day of the Dead had left off; Land of the Dead extends the premise hinted at with Bub in ’85, with the idea that zombies can, to an extent, remember, learn and cooperate. For me though, this creates a difficulty which even Romero couldn’t get past in his final two zombie films, Diary of the Dead (2007) and Survival of the Dead (2009). If zombies can eventually learn to master the things which made them human, what is it which makes them (or keeps them) truly monstrous? Where can this particular monster then go? Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, as devotees of Romero’s earlier work, understood this and went very much back to basics with their stand-out horror comedy Shaun of the Dead in 2004 – their zombies certainly didn’t run. But this is another facet of millennial zombies: it was a familiar enough trope by this point that it could withstand more than being redrawn; it could cope with being sent up, or used for social satire in ways which could now be wholly overt. Fido (2006) is one of my favourite of these kinds of films, a clever skit on the much-vaunted links between zombies and commodification. Other films, like Pontypool (2008) linked a zombie outbreak with the viral spread of language: those who ‘caught’ language would be reduced to mindlessly parroting the same words or phrases, whilst irrevocably drawn to those who still had the command of their own language. It’s a clever idea which lends itself to several interpretations – whilst still being a damn good film, which is also important. So, the zombie has shambled (or sprinted) along fairly consistently, a continual well of inspiration for budget-less new filmmakers at one end of the spectrum, and fodder for a big-budget TV franchise at the other.

What of vampires? The vampire film doesn’t really feel to have been in ascendancy over the past two decades, at least in my admittedly subjective opinion. There have, however, been some stand-out vampire films, typically those which do a similar thing to my preferred zombie flicks: they draw on some familiar aspect of the lore, and take it somewhere altogether thought-provoking. Shadow of the Vampire (2000) is an excellent place to start along those lines, positioning itself at the making of arguably the first horror film, Nosferatu, and mythologising it, turning the making of that film into a horror of its own. 30 Days of Night (2007) took the straightforward idea that vampires thrive in the dark and extended it, by placing it in a sunless Alaskan winter; Let The Right One In (2008) is a charming adaptation of the Swedish novel of the same title, interrogating ideas of friendship and loyalty as the isolated Oskar and his new neighbour Eli form a strange, often beautiful bond. The ambiguity of the closing scenes has never faded for me. Other big-budget outings have used vampires as a plot device, but just as we have the spectre of thinking zombies, so we now have ‘vegetarian vampires’, which, again, seems a development too far…

Supernatural horror, too, has sadly often been confined to multiplex hits like the Paranormal Activity series, or else we have had to ‘borrow’ ghost stories from the Far East, albeit that some of these have been excellent. Demonic possession, whilst an oddly sexist cinematic sub-genre (demons seem to infinitely prefer inhabiting girls) has clung on, with several ‘The Possession of [Girl’s Name]’ titles over the past couple of decades and even a new tendency whereby even deceased females can get taken over by malign forces – see for example Unrest (2006) and The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016). There’s no rest for the wicked; why female flesh in particular is so embattled is an interesting question, but perhaps one we can answer rather blithely by saying that female flesh is so embattled. Haranguing over questions of bodily autonomy has become a fact of life, even in the 21st Century, so perhaps inevitably, films explore these questions in grotesque manner. A film like Deadgirl (2008) brings all of these ideas together: when a couple of misfit boys find an apparently dead, but reanimate female corpse in the basement of an abandoned building, they find an opportunity to assert themselves over her, sexually and proprietorially. Here, with her, they are in control, when the world outside is in a state of flux which precludes them from being who they want to be – who they feel they deserve to be. It’s a grotesque film, but it’s an underrated horror.

Finally for this part of my article, I want to talk about one other as-yet minor, but significant development in cinematic monsters – one which brings us right back to ‘people as monsters’, but has shifted the roots and reasons for the avowedly monstrous behaviour. In the new millennium so far, we have seen a few films which shift the idea of cannibalism away from being something ‘other’, something that happens ‘over there’, to something more akin to a cult practice, existing just behind the facade of polite, normal society – the societies we recognise. In this guise, cannibalism is often treated as empowering and a key part of familial identity: both versions of We Are What We Are (2010, 2013) enact cannibalism as ritual, something without which the dynamics within families are endangered.

Similarly, Habit (2017) explores cannibalism as something like a code for in-group belonging, as well as being something compulsive which draws people to it; it takes the idea of society’s invisible people, people who linger on the fringes of society, and shows us where they might go, and why. The Clare Denis film Trouble Every Day (2001) re-positions cannibalistic urges as a pesky side-effect of an experimental medical procedure, which is also linked to libido, gifting us the vision of Béatrice Dalle as the ‘ill’ Coré, partially eating a man she has just seduced. Finally, Raw (2016) introduces us to an isolated young veterinary student (and vegetarian) whom, after consuming raw meat as part of a hazing ritual, develops intense cravings for human flesh. This film melds philosophical ideas about angst, anxiety and self-knowledge and propels them through a grotesque series of events, and as such, Raw could equally be seen as the tail end of the new French extremity mentioned above. It’s a fitting place to pause.

Look out for the second part of Keri’s examination of the new millennium in horror…coming soon…