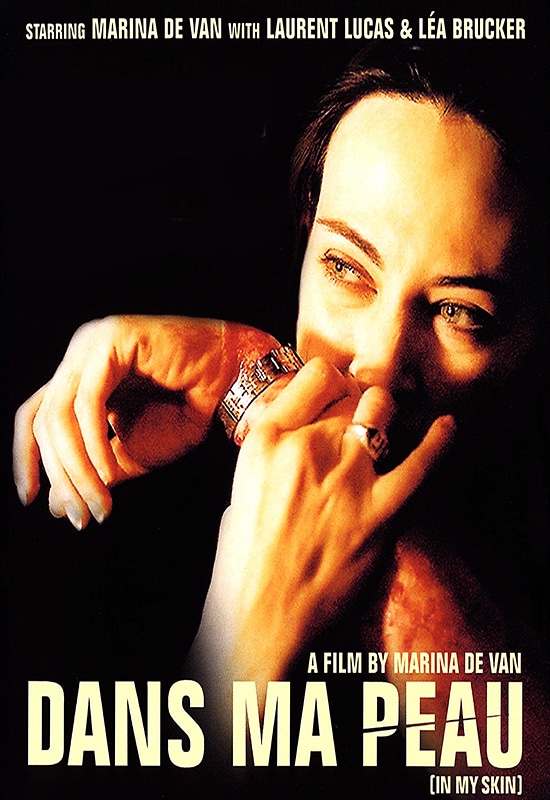

It’s been nearly fifteen years since Dans ma Peau (2004) was released, duly taking its place in the canon of New French Extremity, and garnering a great deal of justifiable praise for its transgressive nature and clarity of vision. These features alone – both the film’s age and its reputation – give us good enough reason to revisit it now. However, looking back, I wonder if its inauguration as a Noughties French horror perhaps worked against some of its strengths. For the horror crowd enamoured of the blue-hued, unflinching gore of the decade, it perhaps seemed not quite a horror film; for those engaged by its domestic and personal themes, perhaps it was too much of a horror film. But these genre-straddling films are often the most rewarding, even if difficult to categorise. Dans ma Peau is absolutely a film which has stayed in my mind – one of those rare birds where I’ve never found my recollection of the film reduced down to a gist memory. it is in so many respects a radical film, and now perhaps more than on my initial viewing, de Van’s tale bloody portrayal of mental breakdown feels like a story for our times.

It’s been nearly fifteen years since Dans ma Peau (2004) was released, duly taking its place in the canon of New French Extremity, and garnering a great deal of justifiable praise for its transgressive nature and clarity of vision. These features alone – both the film’s age and its reputation – give us good enough reason to revisit it now. However, looking back, I wonder if its inauguration as a Noughties French horror perhaps worked against some of its strengths. For the horror crowd enamoured of the blue-hued, unflinching gore of the decade, it perhaps seemed not quite a horror film; for those engaged by its domestic and personal themes, perhaps it was too much of a horror film. But these genre-straddling films are often the most rewarding, even if difficult to categorise. Dans ma Peau is absolutely a film which has stayed in my mind – one of those rare birds where I’ve never found my recollection of the film reduced down to a gist memory. it is in so many respects a radical film, and now perhaps more than on my initial viewing, de Van’s tale bloody portrayal of mental breakdown feels like a story for our times.

The film follows Esther (also the director and writer, Marina de Van), an ambitious young woman seeking greater things – a better job, a better place to live – all the things you catch yourself saying you want, when you get to a certain point. When we first meet Esther, she’s in the throes of negotiating greater professional responsibility; it’s on her mind as she and her friend Sandrine (Léa Drucker) head to a house party. Esther, impressed by the size of the house, heads outside to check out the garden. Whilst she’s out there she stumbles and cuts her leg. Only later does she realise she’s bleeding – quite badly. This immediately distances her from her peers: she covers up the extent of the wound, saying nothing when people comment on the anonymous trail of blood through the house, and she only takes herself to A&E when the night is over anyway.

“Does this leg belong to you?”

Her interaction with the doctor tasked with stitching her up is indicative that something has seismically shifted in Esther’s psyche. She prevaricates about how painful the wound was at the time she received it, giving this as the excuse for not coming to the hospital sooner (we happen to know that the injury hurt when it happened). Her excuses don’t quite ring true with the doctor, who teasingly comments on her lack of ordinary sensation before bandaging her leg and sending her home. Esther, however, has started to re-evaluate her relationship with her own flesh and blood, pinching and pricking at her skin, investigating the leg wound with a strange fascination. There are clues as to why this may be the case. Her boyfriend Vincent (Laurent Lucas, who reprises the body horror in Raw in 2016) takes even the barest glimpse of Esther’s leg as proof positive that she shouldn’t be allowed out to do things on her own without him; she needs to be looked after, he insinuates, thus breezily making a grab for her autonomy. He, on the other hand, has just been headhunted for a new job, and he makes it clear that he sets the agenda in their conversation (and, by extension, their lives). And there we have it, that little gem of doubt and revulsion that so many women feel in their relationships when, were they to speak in open revolt against such gaslighting, they’d be deemed ‘unreasonable’. Little wonder many turn their attentions inwards. Esther’s revolt just happens to be unspeakably graphic.

Pressure – at work and at home – now begins to manifest in (at first) managed, but no less savage sequences of self-harm for Esther. There’s a kind of urgent glee to her actions, a logic almost, which makes them understandable, even if you’d choose not to emulate them. Those close to her, like Sandrine, advocate more conventional means of control, such as pills, but as her career really seems to take off at last, Esther finds that the only way to make life bearable is to continue to exploit her new-found fascination with her body, hacking away at it and even part-consuming it. It is, of course, clear that this cannot continue, but Esther’s determination to balance her job and her self-treatment move forward together. It’s an uncomfortable, but a no less poignant thing to observe.

The France of the film is a fast-paced, rather fraught world that we could all probably recognise. Everyone seems stressed by their work, everyone wants more ‘recognition’ and everyone seems to be struggling to conceal their feelings of anxiety and professional ennui. When the ‘real’ is exposed – such as when Esther’s injury bleeds through a pair of expensive (borrowed) trousers during the poolside scene – misery and vulnerability ensue. People do not like being exposed as different, but they want recognition for being different. It’s the tightrope which many must walk. Outside of the office, the carefully-domineering Vincent is difficult to watch. Whatever germ of genuine concern he might have for Esther, it quickly translates into a need to police her body. The only way a miserable woman can be stopped from self-harm is, evidently, to physically prevent her doing so. His logic is, almost inevitably, part of the problem here. Esther, faced with these escalating situations, feels the need to shut down further. When she cuts herself, she performs the film’s only tender, loving scenes. The camera lingers on these; it’s macabre, but it’s a kind of affection which is absent elsewhere, and the contrast is clear. It’s also heartbreaking that so many of the avenues which seem to be open to Esther either seem lost to her, or self-sabotaged. The hallucinatory sequence at the restaurant, for instance, is a particularly dismal distillation of that feeling, “I don’t belong here”. Hence, you end up making sure that you don’t belong. This all takes place, ironically, as the white-collar dinner table conversation extols the supreme virtues of Paris over other European cities; sadly, Esther’s Paris has few virtues for her.

The France of the film is a fast-paced, rather fraught world that we could all probably recognise. Everyone seems stressed by their work, everyone wants more ‘recognition’ and everyone seems to be struggling to conceal their feelings of anxiety and professional ennui. When the ‘real’ is exposed – such as when Esther’s injury bleeds through a pair of expensive (borrowed) trousers during the poolside scene – misery and vulnerability ensue. People do not like being exposed as different, but they want recognition for being different. It’s the tightrope which many must walk. Outside of the office, the carefully-domineering Vincent is difficult to watch. Whatever germ of genuine concern he might have for Esther, it quickly translates into a need to police her body. The only way a miserable woman can be stopped from self-harm is, evidently, to physically prevent her doing so. His logic is, almost inevitably, part of the problem here. Esther, faced with these escalating situations, feels the need to shut down further. When she cuts herself, she performs the film’s only tender, loving scenes. The camera lingers on these; it’s macabre, but it’s a kind of affection which is absent elsewhere, and the contrast is clear. It’s also heartbreaking that so many of the avenues which seem to be open to Esther either seem lost to her, or self-sabotaged. The hallucinatory sequence at the restaurant, for instance, is a particularly dismal distillation of that feeling, “I don’t belong here”. Hence, you end up making sure that you don’t belong. This all takes place, ironically, as the white-collar dinner table conversation extols the supreme virtues of Paris over other European cities; sadly, Esther’s Paris has few virtues for her.

The thing is though, as far as Esther is concerned, once you can live one lie, you can live more than one. Not effectively, but you can. Esther is willing to perform great feats of concealment to excuse her physical condition; later, de Van’s series of split screens encapsulates Esther’s great divide between real self and unreal self. Only later do they conjoin and show us what Esther’s doing – a kind of performance art of mutilation, done on the quiet in a sequence of ever grubbier, anonymous hotel rooms. It’s in one of these rooms that we finally leave her, having thought at first that, even given her final physical condition (with large cuts and abrasions on her face, and at least one severed piece of skin which she wants to preserve) she is about to attempt to return to her job.

The thing is though, as far as Esther is concerned, once you can live one lie, you can live more than one. Not effectively, but you can. Esther is willing to perform great feats of concealment to excuse her physical condition; later, de Van’s series of split screens encapsulates Esther’s great divide between real self and unreal self. Only later do they conjoin and show us what Esther’s doing – a kind of performance art of mutilation, done on the quiet in a sequence of ever grubbier, anonymous hotel rooms. It’s in one of these rooms that we finally leave her, having thought at first that, even given her final physical condition (with large cuts and abrasions on her face, and at least one severed piece of skin which she wants to preserve) she is about to attempt to return to her job.

But we don’t see this happen. We’re left instead with Esther staring, motionless, down the camera, from the ‘green room’ we thought she’d left for good. Did she ever really leave the room – did she retreat? Or did she have to check in there again after the almost inevitable end of her pretences? Is she, in fact, finally free of the things which drove her to this behaviour in the first place, and back at the room as a free agent? Given her joyless expression, this seems unlikely. There’s little evidence of a redemptive ending here.

Dans ma Peau is a film which subverts expectations whilst offering surprisingly sensitive handling of mental turmoil and, although it hinges de rigeur upon a woman’s bloodied body, the agent of this violence is the woman herself, not some nameless, faceless assassin. Coming out of what we can call the ‘torture porn arc’, it’s interesting to note that here the unflinching, even fetishistic focus on bodily injuries comes to us as an individual’s attempts to cope with their life. Usually, people seek to flee injury. In this film, Esther flees towards it. Her fate is ambiguous, sure, but the justifications for the on-screen violence here must stand alone. Dans ma Peau has a great deal to distinguish it from its peers. It also strikes me now as a film which has an awful lot to say about people’s lives, using its extreme violence to hold a mirror to the other things which people do to themselves in order to cope with the various screeds we live by. If not physically slashing at ourselves, what else do we do? And does it work?

Dans ma Peau a singularly uncomfortable film to watch, then, commanding sympathy whilst also repelling us. The violence is far more implied than shown, but Dans ma Peau still settles on the mind as a particularly nasty film. But ultimately, I think it affects me most as a deeply sad film, a film which I care about the protagonist and will always wonder about the end of the story. In that respect and to that extent, I don’t think anything approaching it has really followed in the past decade and a half.