By Keri O’Shea

As a willing outsider to parenthood, it’s not too much of a reach for me to see the whole thing rather as some very fine horror movies have seen it – as something alienating, pervasive and often irrational. Having children is something most people sign up to eventually, or often yearn to if they can’t, and then ask repeatedly if you’re going to sign up, too. Being a parent confers status, but it also shifts a person’s priorities completely; it’s one hell of a fork in the road. As for pregnancy and childbirth itself, it may have stopped killing women (in the West) in the numbers it once did, but it still walks hand in hand with invasive medical procedures, pain and discomfort, lethargy, sickness, physical damage and of course, mental health issues. All of this is, of course, ‘worth it’ and, as I’m regularly assured, I’m just one of those awful childless women who doesn’t understand – but, hey, even if mainstream culture is still reticent on the dark side to raising a child, then horror cinema has long embraced it, both squirming at the physical aspects of pregnancy and holding a mirror to the life-subverting aspects of bringing up baby too. Rosemary’s Baby, a classic of this kind for good reason, positions Rosemary’s pregnancy as something quietly monstrous, sapping her strength and then her autonomy as she’s manipulated and sedated in turn. She is given one opportunity for revenge and reassertion of self, but instead capitulates to her maternal instincts. Other films look more closely at the role of the baby itself, such as Grace (2009), which pushes the draining physical demands made by a newborn into more grotesque, if understated body-horror territory – again, pushing the mother away from her friends and family, her instincts compelling her to nurture her child at all costs to her.

This brings us to Shelley (2016), a film with similar subject matter and some similar developments to the above, but which – on reflection – is more subtle and ambiguous, defying any neat summary, yet one of those rare films which dares the disapproval of all of those folks crying out for neat summaries.

The film begins with a young Romanian woman, Elena (Cosmina Stratan) being driven to her new place of work, where she’ll be acting as housekeeper and assisting Louise (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), who is recuperating after an illness. Louise and her husband Kasper (Peter Christoffersen) live an isolated and largely self-sufficient life on their small Swedish estate: there’s no running water, no electricity (the New-Agey Louise seems to actively fear it) but the married couple seem fine with their no-mod-cons existence, and the house’s environs are indisputably serene and beautiful.

The film begins with a young Romanian woman, Elena (Cosmina Stratan) being driven to her new place of work, where she’ll be acting as housekeeper and assisting Louise (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), who is recuperating after an illness. Louise and her husband Kasper (Peter Christoffersen) live an isolated and largely self-sufficient life on their small Swedish estate: there’s no running water, no electricity (the New-Agey Louise seems to actively fear it) but the married couple seem fine with their no-mod-cons existence, and the house’s environs are indisputably serene and beautiful.

Elena and Louise begin to bond – first, via conversations about Elena’s little boy, Nicu, whom Louise asks after. Elena explains that he’s living with her parents back home while she works to save money for them both. It soon transpires that Louise has suffered miscarriages and the ensuing complications led to her womb being removed; this is clearly a subject which causes her profound pain. Off the back of this frankness, a warm, believable friendship between the couple and their employee soon follows. Elena teases them for their unusual lifestyles, they tease her back, and it seems as though the presence of somebody new has added some fresh energy to their home.

One evening, Louise asks Elena if she would consider surrogacy for her and Kaspar. Their payment for this, she explains, could enable Elena to go home to her son far sooner, and secure the apartment she wants for them both. After careful thought – and a mother’s desire to do right by her little boy – Elena accepts, and the reception of this news by her hosts is genuinely sweet. The implantation of Louise’s egg and Kaspar’s sperm is successful and Elena’s pregnancy progresses – but soon, she begins to suffer nightmares, then minor adverse symptoms which worsen. Louise, seeming genuinely alarmed, is worried about her, though medics assure them both that the baby is fine: however, Elena is convinced that something is wrong and begins pleading to leave.

The film could have began to flounder at this stage, painting the rest of its plot in foot-high letters and adding a pentagram at the end for good measure (as is conventional). By the time half of the film had passed, I found myself hoping against hope that this wouldn’t be the case, and thankfully it isn’t: to do so would have rendered the slow, meticulous build-up of atmosphere null and void. Shelley isn’t an exercise in clear exposition, and its mood is not generated to lure viewers into a false sense of security before a change of tack. What it does superbly it does oh-so quietly, and it maintains this approach throughout.

Things are shown to be out of kilter – quite aside from the mesmeric, deeply-unsettling sound design courtesy of Martin Dirkov – in unassuming ways. The clean Scandinavian interiors have flies crawling in cupboards; Louise swigs from a bottle of red wine, all the while extolling the virtues of clean living; there’s something faintly hollow about the quiet happiness on offer. Also the way the narrative skips – from Elena’s warm agreement to being a surrogate through to a cold, functional medical procedure, for instance, lends the film an episodic, dream-like quality which can feel exclusionary and unsettling. We are led to feel exactly as Elena (with whom we spend the most time as a character) must feel. The ‘good news’ of her pregnancy reinvigorates Louise and Kaspar’s sex life; as they grow closer, more intimate, the person facilitating it all is shut out even more. Elena’s nightmares may be just that, or they may be supernatural, but unquestionable is her loneliness, and as pregnancy weakens her physically, she begins to recede as a person. Louise seems genuinely alarmed by her surrogate’s condition, but attempts to help her strip Elena of even more autonomy. She’s given ‘healing treatments’ she didn’t ask for, given nutritious food which doesn’t match what she chooses to eat, and is grilled on her behaviour. Louise is no monster (Kaspar, however, grows ever more absent) but it’s impossible not to feel sorry for this poor girl, in a strange country, away from her family, growing increasingly vulnerable as her pregnancy – or is that Louise’s pregnancy? – develops.

One of the brief downsides to this character-centred approach is that little is truly made of the sylvan setting; the press release mentioned the house being a significant presence in the film, for instance, but on balance I disagree. Where these people live is relevant in terms of their isolation, and of course Elena’s distance from home, but otherwise, people’s internal worlds seem more developed and are given far more attention on-screen. Still, the rare skill invoked by first-time feature (!) director Ali Abbasi weaves a complex tale, and leaves us with questions which I feel could definitely be rewarded by repeat viewings. Is Shelley pre-partum psychosis writ large? Is it a parable on human exploitation? Is it about the all-consuming effects of maternity, or is there – is there – something more otherworldly behind it? These things I don’t know, but the film is better, not worse for it. It’ll be too quiet, too arty for some, and any answers it provides are inconclusive, but I’ve never before seen a film which marries the idea of starting a family to such an utter sense of dread, and as such I think it’s a unique and defiant piece of work.

Shelley will be released on DVD and download on the 10th October, 2016.

An email was sent out recently by a well-established website who are seeking new writers to help them keep on top of the relentless flow of tidbits and news which fans might like to read. People applied to find out more, and received the following reply from the site in question – and I’m not going to play coy here, the site in question was HeyUGuys:

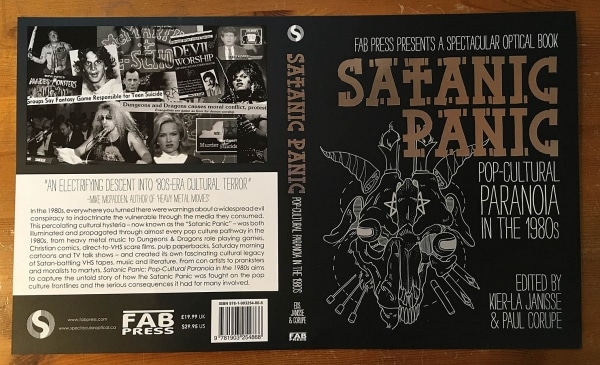

An email was sent out recently by a well-established website who are seeking new writers to help them keep on top of the relentless flow of tidbits and news which fans might like to read. People applied to find out more, and received the following reply from the site in question – and I’m not going to play coy here, the site in question was HeyUGuys: The so-called ‘Satanic Panic’ of the Eighties (with some fallout in the following decade) is a curious phenomenon – one born out of a collision of new media, psychiatry, pop-psychiatry and pop culture. It’s one of those things which could – and did – run and run, borne aloft by its ‘hidden’ status (how do you disprove a secret?) and of course its seductive promise of illicit sex, cult activity, crime and murder – all available for concerned parties to enjoy, whilst simultaneously fretting and disdaining it all, of course. Various theses and books on the subject have appeared piecemeal over the years, but never before has there been such an exhaustive examination of the phenomenon as offered by the recent FAB Press release Satanic Panic – a book which brings together a number of commentators and invites them to offer their expertise on the topic in their own particular styles and from their own perspectives.

The so-called ‘Satanic Panic’ of the Eighties (with some fallout in the following decade) is a curious phenomenon – one born out of a collision of new media, psychiatry, pop-psychiatry and pop culture. It’s one of those things which could – and did – run and run, borne aloft by its ‘hidden’ status (how do you disprove a secret?) and of course its seductive promise of illicit sex, cult activity, crime and murder – all available for concerned parties to enjoy, whilst simultaneously fretting and disdaining it all, of course. Various theses and books on the subject have appeared piecemeal over the years, but never before has there been such an exhaustive examination of the phenomenon as offered by the recent FAB Press release Satanic Panic – a book which brings together a number of commentators and invites them to offer their expertise on the topic in their own particular styles and from their own perspectives. Hello, Happy New Year, and welcome to our new project, Warped Perspective…

Hello, Happy New Year, and welcome to our new project, Warped Perspective… Unless something else just sneaks under the wire over the next couple of weeks, it seems this could be my final Horror in Short feature for the current site. Huh. It feels like only yesterday that I decided it was high time we spent more time championing these often brilliant, inventive and grossly-underrated cinematic projects; and now here we are, years down the line, many films covered, and as usual, I was right. Happier still, today’s likely last short film – Remnants – is a stylish, well-paced offering which is clearly aware of its horror heritage, but has something pleasantly smart and knowing to say in a mere fifteen minutes. Take a look for yourselves, folks, before you read the review which follows…

Unless something else just sneaks under the wire over the next couple of weeks, it seems this could be my final Horror in Short feature for the current site. Huh. It feels like only yesterday that I decided it was high time we spent more time championing these often brilliant, inventive and grossly-underrated cinematic projects; and now here we are, years down the line, many films covered, and as usual, I was right. Happier still, today’s likely last short film – Remnants – is a stylish, well-paced offering which is clearly aware of its horror heritage, but has something pleasantly smart and knowing to say in a mere fifteen minutes. Take a look for yourselves, folks, before you read the review which follows…

This brings me to What We Become (2015), a film which is oddly enough not the first Danish zombie film I’ve ever seen, giving the lie to the trivia section of its IMDb page, but oddly enough, it labours under a lot of the same issues that I talked about five years ago when I reviewed its predecessor,

This brings me to What We Become (2015), a film which is oddly enough not the first Danish zombie film I’ve ever seen, giving the lie to the trivia section of its IMDb page, but oddly enough, it labours under a lot of the same issues that I talked about five years ago when I reviewed its predecessor,

The film begins with a young Romanian woman, Elena (Cosmina Stratan) being driven to her new place of work, where she’ll be acting as housekeeper and assisting Louise (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), who is recuperating after an illness. Louise and her husband Kasper (Peter Christoffersen) live an isolated and largely self-sufficient life on their small Swedish estate: there’s no running water, no electricity (the New-Agey Louise seems to actively fear it) but the married couple seem fine with their no-mod-cons existence, and the house’s environs are indisputably serene and beautiful.

The film begins with a young Romanian woman, Elena (Cosmina Stratan) being driven to her new place of work, where she’ll be acting as housekeeper and assisting Louise (Ellen Dorrit Petersen), who is recuperating after an illness. Louise and her husband Kasper (Peter Christoffersen) live an isolated and largely self-sufficient life on their small Swedish estate: there’s no running water, no electricity (the New-Agey Louise seems to actively fear it) but the married couple seem fine with their no-mod-cons existence, and the house’s environs are indisputably serene and beautiful.

Where the film parts ways with the aforementioned series, however, is in its real-life historical basis. The director of The Last King, Nils Gaup, made a Viking-themed film titled Pathfinder in the 1980s (a film I love, though I take issue with some of the characterisation). Well, his most recent feature is far more firmly anchored in realism, though coming from that intersection between myth and history which usually arises with a good yarn. Coming post-Viking Age, the film is set in Norway in the year 1204. Although Norway has been Christianised by this point, as elsewhere in Europe the whole ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’ gambit has been ignored in favour of factionalism and brutal attempts to seize power; Norway is divided into small kingdoms, with the East Norwegian/Danish alliance, the Baglers, vying for control over the independent West. Fearing imminent invasion, the king sends some of his loyal Birkebeiners to escort his illegitimate baby son Håkon Håkonson – and the baby’s mother – to safety, ahead of the invading army. Illegitimate or not, the boy is in line to the throne, and will be killed if he’s discovered and identified. However, what seems initially to be a successful mission is thwarted by traitors in the king’s camp, who see the two friends – Torstein and Skjervald (Lilyhammer’s Jakob Oftebro) – taking the child to safety. Skjervald is followed and information as to little Håkonson’s whereabouts is brutally extracted from his young family. There’s our coming vengeance angle, then – but can the Birkebeiners prevent an overthrow of power which seems to come as much from within the country as without? Life at court is just as fraught with risk and duplicitious goings-on…

Where the film parts ways with the aforementioned series, however, is in its real-life historical basis. The director of The Last King, Nils Gaup, made a Viking-themed film titled Pathfinder in the 1980s (a film I love, though I take issue with some of the characterisation). Well, his most recent feature is far more firmly anchored in realism, though coming from that intersection between myth and history which usually arises with a good yarn. Coming post-Viking Age, the film is set in Norway in the year 1204. Although Norway has been Christianised by this point, as elsewhere in Europe the whole ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’ gambit has been ignored in favour of factionalism and brutal attempts to seize power; Norway is divided into small kingdoms, with the East Norwegian/Danish alliance, the Baglers, vying for control over the independent West. Fearing imminent invasion, the king sends some of his loyal Birkebeiners to escort his illegitimate baby son Håkon Håkonson – and the baby’s mother – to safety, ahead of the invading army. Illegitimate or not, the boy is in line to the throne, and will be killed if he’s discovered and identified. However, what seems initially to be a successful mission is thwarted by traitors in the king’s camp, who see the two friends – Torstein and Skjervald (Lilyhammer’s Jakob Oftebro) – taking the child to safety. Skjervald is followed and information as to little Håkonson’s whereabouts is brutally extracted from his young family. There’s our coming vengeance angle, then – but can the Birkebeiners prevent an overthrow of power which seems to come as much from within the country as without? Life at court is just as fraught with risk and duplicitious goings-on…

When they do, what we see is a fairly robust and stylish set of visuals – based on first impressions, presumably there’s at least some cash and some clue behind this project, as shown by the prettily-shot woman bathing in (and, for want of a better expression, gargling with) blood. Furthermore, there’s an early surprise when we seem to start with urban horror, as police discover a gruesome scene within the confines of an otherwise normal apartment block in Seattle. Still, this turns out to be a parallel plot line: as a detective tries to get to the bottom of what happened in the apartment, an expected group of twentysomethings are indeed getting ready to head into the boonies for a 4th July party. A few unnecessary lines of dialogue tell us that there is limited cellphone signal at the cabin they’re staying in, and as ever I’m unclear on whether this group of old schoolfriends are meant to be hateable or relatable, but feeling called upon to ponder this now seems as ubiquitous a part of cabin-based horror, for me, as the bikinis and the weak bottled beers.

When they do, what we see is a fairly robust and stylish set of visuals – based on first impressions, presumably there’s at least some cash and some clue behind this project, as shown by the prettily-shot woman bathing in (and, for want of a better expression, gargling with) blood. Furthermore, there’s an early surprise when we seem to start with urban horror, as police discover a gruesome scene within the confines of an otherwise normal apartment block in Seattle. Still, this turns out to be a parallel plot line: as a detective tries to get to the bottom of what happened in the apartment, an expected group of twentysomethings are indeed getting ready to head into the boonies for a 4th July party. A few unnecessary lines of dialogue tell us that there is limited cellphone signal at the cabin they’re staying in, and as ever I’m unclear on whether this group of old schoolfriends are meant to be hateable or relatable, but feeling called upon to ponder this now seems as ubiquitous a part of cabin-based horror, for me, as the bikinis and the weak bottled beers.