It’s great that HollyShorts is around: the more festivals we have covering the world of short genre film, the better. As an example of the kinds of films they have featured this year, here are just four titles: each diverse, but each compelling examples of the short film format.

First up is Halfway Haunted, which starts with a woman practicing for a job interview, running through what she’s going to say, making sure she feels ready for the big day. However, there are some issues: first of all, there’s a huge pool of blood seeping through the ceiling. Then her bottle floats into the air, before smashing on the ground. Oh, and did I mention the severed head in the fridge? Yep, Jess (Hannan Younis) lives in a haunted house, although she seems strangely used to it, and more annoyed than terrified.

Things kick up a gear when the property gets sold out from under her and she has to suddenly contend with a brand new, smiling assassin of a landlord called Stephanie (Sugar Lyn Beard). Stephanie wants Jess gone so she can bulldoze and redevelop the place, but Jess isn’t really in a position to find a new place right now. However, if Jess is reluctant to let these kinds of changes take place, then so – it seems – is the ghost.

This is one of those quirky takes on the afterlife which does more than enough to keep things interesting, with a sharp script, suitable pace and diverse moments of humour, making smart points about class, wealth and housing whilst never losing sight of the fun fantasy elements at play. Stephanie is a great villain, Jess is a worthy protagonist, and everything else which director Samuel Rudykoff finds time to show to us works well with the whole. There are twists and turns, too, so you can’t get too comfortable with what you expect is going to happen.

Then there’s a period piece titled The Pearl Comb: it’s a very different beast, though it, too – coincidentally – offers a take on the supernatural, though more with specific folklore in mind. The film starts in Cornwall, 1893: a young doctor named Lutey (also director Ali Cook) is visiting a relative, a woman named Betty (Beatie Edney) who has made the grand claim to have cured a case of consumption – then an incurable and progressive disease which laid waste to people of all walks of life. Dr. Lutey is of course intrigued, but he detects issues with Betty’s story and with her apparent ability to cure the sick. She explains that she owes her abilities to her late husband. Before his passing, he nursed her for an ailment of her own, but a strange encounter one day saw him seduced into a strange bargain with a mysterious creature.

Much of the film belongs to Betty’s husband – known simply as Lutey (Simon Armstrong) – and the events which befell him. The film looks amazing, with meticulous, painterly period detail, just the right amount of fantastical CGI to world-build what is revealed to Lutey as perhaps real, perhaps fantasy, and a great set of actors, who look like they lived these parts. The Pearl Comb offers a vivid and engaging version of a well-known kind of folk tale, but it does more than that too – bringing in aspects of magic vs realism, gender and agency. It’s a sublime spin on the short film format, and another example of how much can be done with such a short runtime.

Next up is a film titled Plastic Surgery: it makes its points in a clear and very literal way from title to content, but it’s none the worse for this, and perhaps it’s the literal lesson people need in order to see what the film is saying.

Dr Terra (Anna Popplewell) is a surgeon specialising in the removal of ‘foreign bodies’ (now there’s a phrase which can speak many volumes). She’s about to go on maternity leave, so her spirits are pretty high – but the end of her shift gets surprisingly, nightmarishly busy, with a sudden influx of people all needing her help to remove a variety of items. As her expertise is called on again and again, Plastic Surgery becomes something of a body horror, albeit one with an environmentalist flair: the foreign bodies in question are all disposable plastics. It’s unpleasant and it’s discomfiting, but it’s a great perspective on just how choked by plastics we really are.

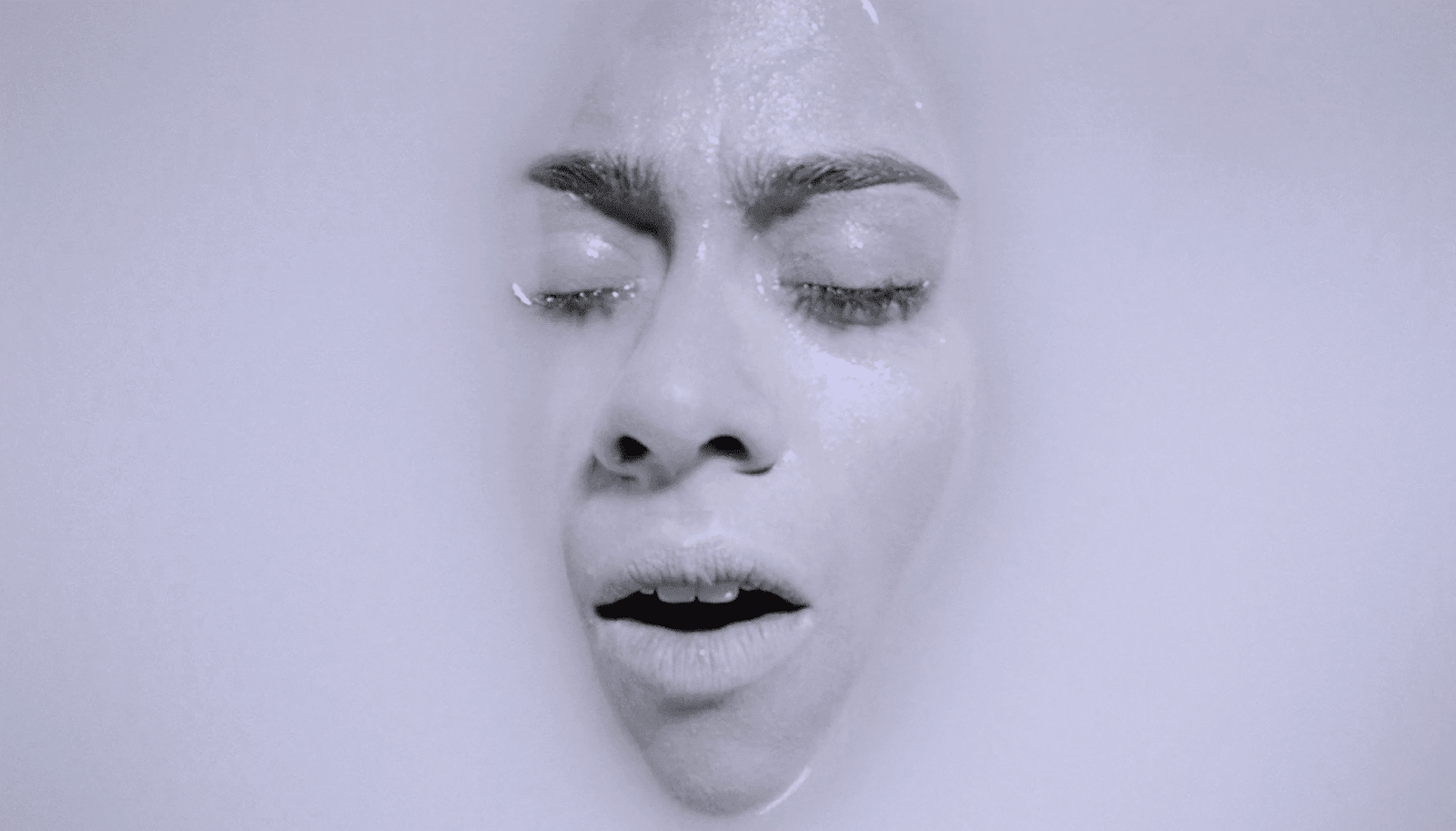

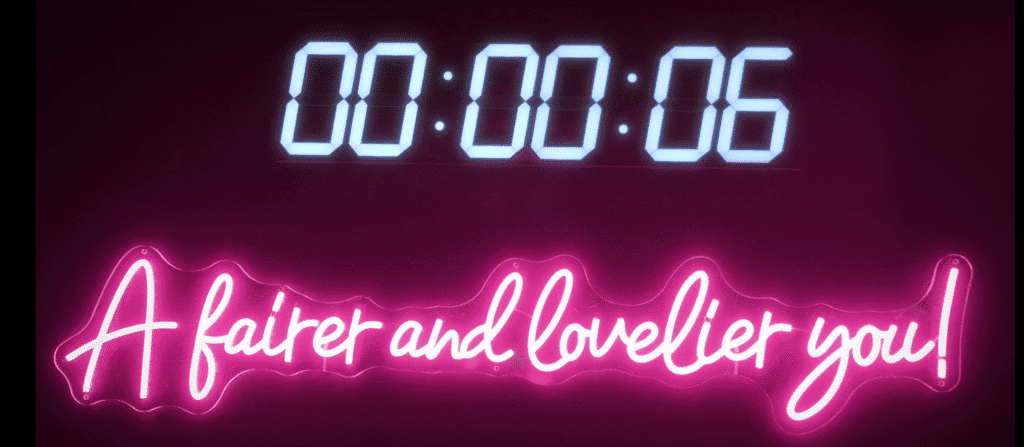

Finally, there’s Skin: a young woman, Kanika (Shreya Navile) is on her way to her first skin bleaching session. We can see that she’s preoccupied with her skin tone, as we see her scrolling through her image gallery, tweaking the levels on her selfies until she appears as pale as possible. Her sister Ria (Sureni Weerasekera) is not interested; more than that, she’s horrified that her own flesh and blood would fall in with such a nonsense beauty norm. But Kanika is unswayed, and heads into the clinic.

Clinics in horrors, sci-fi and anything close are always oddly terrifying places and this one is no exception. Kanika’s treatment requires her to immerse herself in a milk-white liquid, which she does, but there’s something off about the whole set-up here. Outside, and in agreement with that sentiment, Ria makes the decision to intervene and when she gets inside, she sees far more evidence of the clinic’s strange practices. The thing is, they might want Ria to stay, too…

There are clear elements of The Substance (2024) in here, though shifted around to examine a skin tone perspective, rather than a more straightforward set of anxieties about ageing. Nonetheless, Skin is its own beast, doesn’t need to be super-subtle to make its point, and uses striking visuals to do it. It’s pretty certain that the beauty industry will continue to generate very specific horrors, and Skin a welcome entrant to that genre, especially considering its handling of a non-white perspective – relatively rare for now, but again, that will almost certainly change.