Home Invasion (2023) is not your standard style of documentary; there’s no talking heads here, no voiceover, no familiar features as such. Instead, it all unfolds via on-screen text, which displays to viewers via what looks like an aperture, representing the film’s key subject matter (or at least, key for the first hour): the home security doorbell. Text takes us through the film’s key ideas and falls broadly into chapters, even though – for all the text used – chapters do not explicitly appear. The result of all this? A strangely trancelike experience, blending images, footage and film clips with a hypnotic, dark ambient soundtrack. Its range is expansive – perhaps too much so – but despite a few quibbles or issues, it remains an intriguing project which at the very least comprises a very interesting array of Ring doorbell footage, enough for a scary and unsettling film in its own right.

We don’t get straight to that, however. Instead, Home Invasion begins by describing the birth of home security. In 1966, a nurse, Marie Van Brittan Brown, woke up after a nightmare of home invasion, probably triggered by a burglary which she felt was not taken seriously enough by police. This led to her feeling unsafe at home, and distrustful of existing measures to tackle these feelings, so she invented new technology: a new doorbell system, with peepholes and a video camera. She became obsessed by the feed; in a sense, as the film suggests, this was a new kind of home invasion in some respects. Ironically, her ideas were picked up and used by people better off than her, in homes she’d never have lived in. But surveillance, as we understand it today, was born.

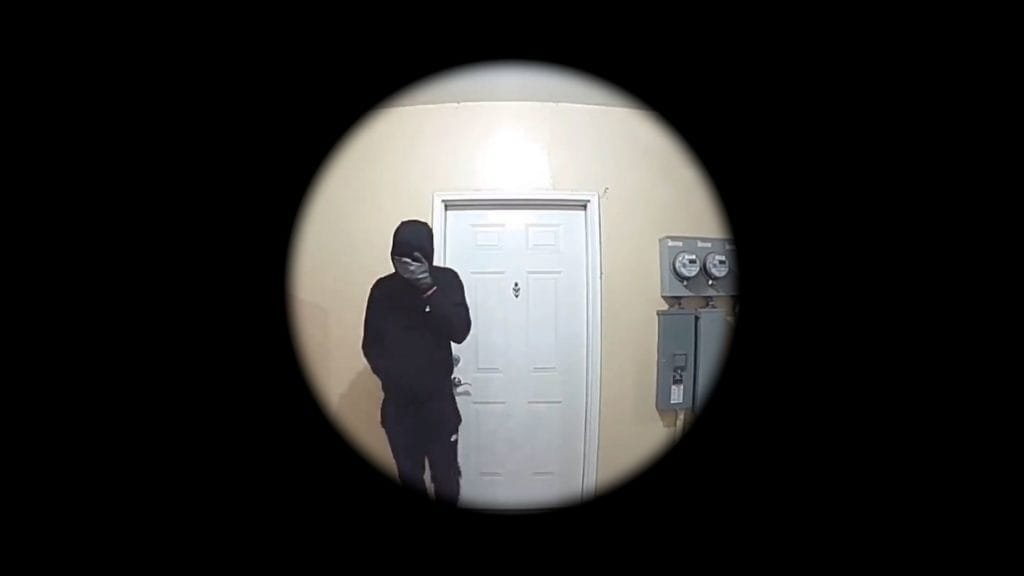

At this point, the film begins to bring in clips of doorbell footage, and takes a short breather from the on-screen text. We next learn about the creator of Ring, an at-the-time depressed and unsuccessful businessman called Jamie Siminoff who invented the live feed doorbell, at first called ‘Doorbot’, but later Ring (despite bombing on the reality TV show Shark Tank, it was later bought out by Amazon; you may know the rest.) This extends the process developed by Van Brittan Brown, affording the possibility of a security network where one can look right back at the people seeking access to your home. The power dynamics suggested by the film are interesting; it also points out that fear became an important selling point in the Ring promotional material, though to be fair, a lot of people seem to use it simply to negotiate with delivery companies (and there’s quite a lot of footage of that going on). It’s also quite interesting to come to this from the perspective of a non-user with no plans to ever use Ring; perhaps we could debate how successfully the fear agenda being proposed has actually landed, and some statistical information would be useful too. Nonetheless, there is a great range of footage here, ranging from the genuinely scary (no Ring doorbell in the world can see through a ski mask) to the diverting, to light entertainment (animals seems pretty good at triggering doorbells).

It’s clear that there is a certain political agenda at play here: as the film continues, the wording on the screen becomes more overt, after asserting that Ring may push a ‘racist and classist’ agenda, it goes further, suggesting – for example – that neighbourhood watch-style messageboards sharing Ring footage are “riddled with police”. ‘Riddled’ is clearly a loaded term; of course questions around purported falls in crime rates since Ring went into common usage deserve examination, though this is likely to fall in with older discourse around the ‘panopticon’ and what it does to human behaviour. And, these ideas are certainly citable. But, on its own merits, the clips compiled here are very interesting; this is the film’s real high point, and having to use your senses to work out what you are seeing is a strangely disconcerting experience (again, this may feel differently depending on whether you use this technology, or not).

The remaining sections spread their net very widely; the final chapter-ish feels like a chapter too far perhaps. After Ring, we move back in time to the role of the telephone (being integral to the functionality of Ring) but here, Home Invasion concentrates more on the role of the telephone in horror cinema, which it didn’t do earlier with newer technology; in fact, this is interesting as an approach, given that home invasion itself forms a horror subgenre, often encompassing CCTV, smartphones and similar. But the range of clips used during the section on the phone (which suggests that the phone once and for all revolutionised our understanding of time, place and interaction) are engaging.

From here, and maybe offering an antidote to what by now feels like an inexorable tide of tech, controlled by institutions and corporations who do not have the best interests of the common person at heart, we go back in time again to the Luddite movement. For this reviewer, this long final section sacrifices some of the film’s forward impetus; presenting the Luddites as evidence that a new way can be negotiated between people and technology isn’t fully convincing, given we know how that went; it’s tough to think of any other reason it’s in here. Two centuries later, we are pondering if AI is going to rise up and kill us. The film also needs a good proofread, given its dependence on text as a medium: there are noticeable inaccuracies, from apostrophes to the use of clunky or non-existent words like ‘logics’ and ‘violences’.

Still, despite some of these issues, as an overall project Home Invasion still has plenty to recommend it: its unorthodox, ambitious approach conveys a wealth of important, engaging information, and it’s done a superb job of assembling its footage, all packaged by a nightmarish soundscape which works really well. It’s not a horror film, but it very much could be in places.

Home Invasion featured at the Fantasia International Film Festival 2023.