The Artifice Girl (2022) comes straight to the point in its opening scenes, as Special Agent Deena (Sinda Nichols) asks Siri – in amongst its other, more straightforward household tasks – to distinguish between right and wrong. It can’t, and it’s this disconnect between technology and the human condition, not to mention our strenuous and possibly self-defeating efforts to erode that disconnect, which forms the bedrock of this film. The Artifice Girl asks, ‘What are we doing?’, stops off at the rhetorical, ‘Oh god, what have we done?’ and then heads over to, ‘Well, what should we do?’

Deena is tacitly asking the first of these questions now as her work, always deeply challenging, is about to enter a new phase altogether. Her investigations concern predators who groom and abuse children online; alongside partner Amos (David Girard), we next see her questioning someone called Gareth (director Franklin Ritch), an SFX expert who has lately permitted a film to be completed after the actor’s death by generating a CGI version of same. I mean, we’ve been routinely doing that for years – sorry, Ollie Reed – but CGI is getting better and better, with the prospect of things like deepfakes now behind new anxieties. As such, you expect Deena’s interrogation of Gareth to turn up something unpalatable, something unspeakable in his conduct. Her tone is accusatory; Gareth is a pioneer, but she’s all too keen to remind him of the swirling morass of ethical quandaries lurking just behind his skill set. Steadily, she zones in: there’s far more to this than rendering someone’s image for the purposes of making a film, and it suggests that he has been up to nefarious activities in his own time. It’s a tense, protracted opener, with warring sets of motivations and that debate on right vs. wrong again. It comes down to this, though: what’s acceptable when it comes to tracking predators?

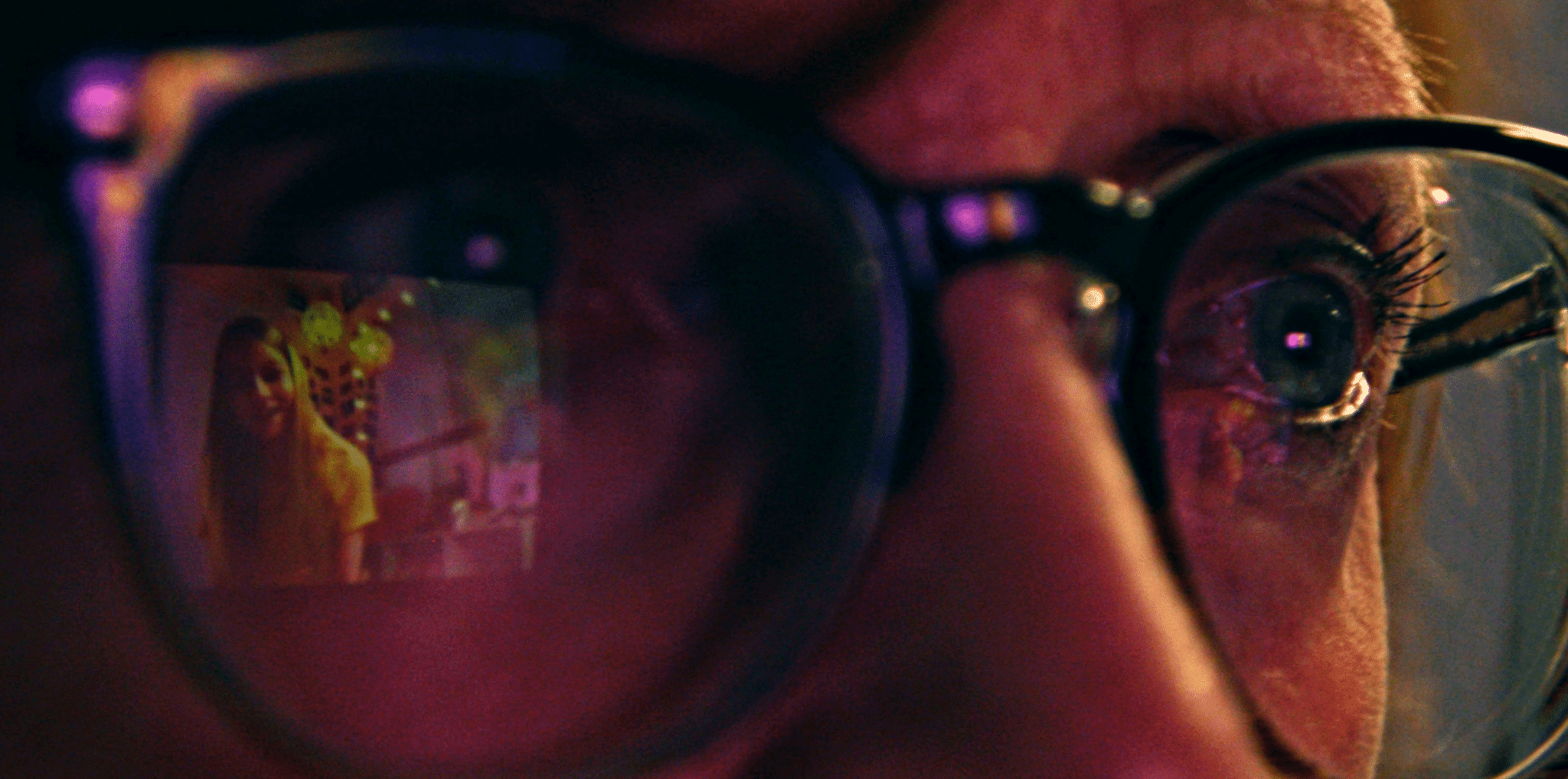

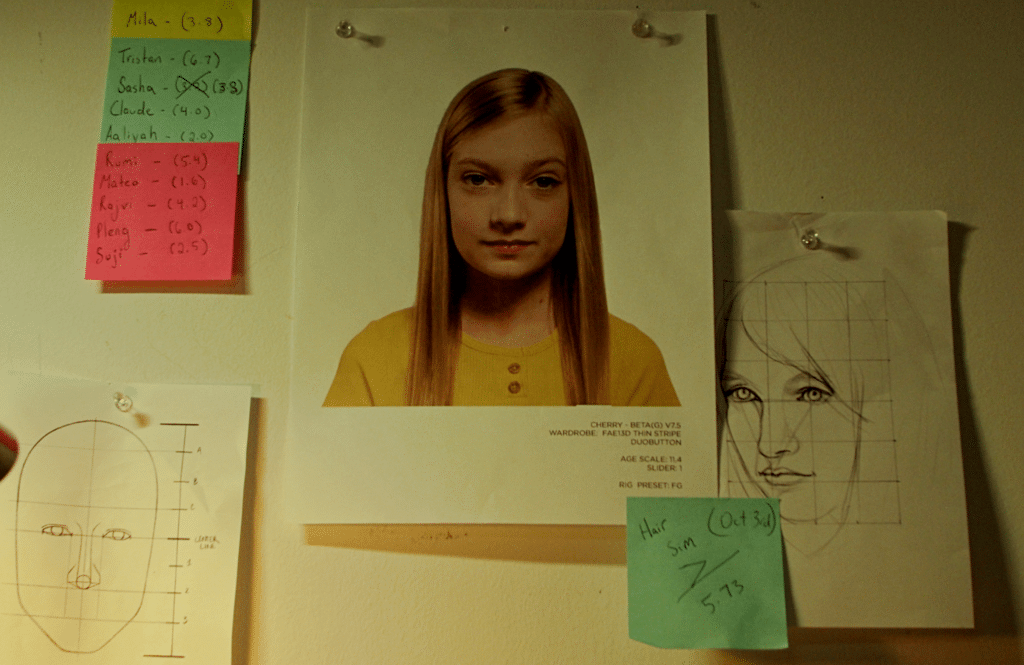

Gareth isn’t in fact a suspect, but he has been working on a programme which is tailored to dupe even the most cautious groomer; it’s this which interests Deena and Amos. Called the Cherry Programme, it is a startlingly convincing emulator, which in turn reflects the ways in which AI boundaries are now seemingly shifting month by month, exploding our notions of reality as they go. At their worst, the new frontiers of AI offer a worrying spin on the old adage, ‘Nothing is real, everything is permitted’: discussions of morality, whether about the rights of the human beings whose work is purloined by the programmes which then spit out convincing facsimiles, or about the ethics of engagement with systems which mirror ‘us’ so well, are everywhere. The Artifice Girl primarily picks up on the latter aspect, though from the interesting perspective of doing good, rather than ill, via deception. This underpins much of the film’s first two chapters (this is a film very much of its time in more ways than one, so yes, there are title cards in here). The concept of ‘Cherry’ is interesting, though the film as a whole is very, very dialogue-heavy, grounded in human interaction as the human characters thrash out their thoughts. There’s been a spike in very low-key science fiction of late where technological advancement is shown in the detail, in how it affects people in the minutiae of everyday life, and this is another one of them, pared back even more than has become usual – even when Lance Henriksen appears.

The film has, mind, selected two of the most emotive themes it possibly could have, then considers them together. The concept of intelligent AI, as explored through the idea of the Cherry Programme, is a queasy reminder of the incumbent issues around ‘intelligence’ and ‘personhood’ and how these may develop. Also, taking CSE as a key plot point – as much as this subject is treated obliquely – brings the whole Cherry Programme idea into a particular focus. (There’s one plausibility issue in that, given the time the programme eventually runs, it wouldn’t become anecdotally known to the people it is meant to catch.) On the whole, genre film tends not to shy away from this topic, though here we have a film keeping up with the technological potential to tackle (or facilitate) it, and this is key: humans have driven developments in AI, but then struggle not to engage with AI in good faith, as equals. 40,000 years of evolution on our part makes us vulnerable to reading computer programmes as genuinely human, with genuine human emotions. It’s been there for the earliest days of computer programming, with the Eliza project being developed as early as the 1960s. here, Amos in particular struggles with it, speaking to Cherry as if she were fully sentient. Perhaps the film shifting gears once more – as it drives towards a more tense, if still philosophical plot development – is where it crosses into more familiar territory with a familiar-feeling conclusion, as nicely-handled as it all is. But the dilemmas generated by this forward-looking, innovative computer programme are consistently engaging.

The Artifice Girl retains a kind of late-night debate show feel throughout, with its low lighting and philosophical talking heads, taking on subjects such as free will, consent, capacity, responsibility and decision-making. There’s nothing flashy here, and this categorically isn’t a horror, sci-fi or other genre film about the march of the machines; it’s far more ‘Bicentennial Man’ than Lawnmower Man (and don’t laugh: that latter film was shockingly cutting edge, once). This preference for semantics over spectacle may potentially mean the film struggles to find an appreciate audience, as film viewers often want something more than (mostly) metaphysics in their ninety-minute windows. But it’s worth sticking with this one, as it offers a decent, often sensitive balance of pertinent plot points as it all unfolds.

The Artifice Girl (2022) will be released by Vertigo on digital platforms on the 1st May, 2023.