On The Edge sees filmmakers Jen and Sylvia Soska back at the helm: here, writing, directing and producing an original feature once again. You may, if you look around, see it being vaunted as a ‘psychosexual’ piece of work, a film targeted at an 18+ audience and, through its use of nudity, BDSM and kink, simply guaranteed to agitate the censors. Hmmm. Here’s what will agitate most viewers far more: the student film quality, the shaky performances, and most of all the chippy, naive belief that all of this nudity is somehow edgy, somehow enough – if you add in a dash of dick torture, that is. On The Edge is a bizarre regression in quality, if not quantity; it’s all crass self-indulgence, flimsy moral message and nylon knickers. It’s absolutely astonishing.

As an American politician pontificates about ‘family values’ on the TV, a woman serves breakfast to her twin daughters, wink wink (the Soskas are way more interested in twins than most people are). Shame that dad (Aramis Sartorio/Tommy Pistol) arrives and possibly symbolically disrupts the meal by spilling it all over the floor – where it stays, by the by. But he’s out the door on a business trip, so it’ll be for mom (Sylvia Soska) to clean up: no mean feat in a bodycon dress. Anyway, we follow dad Peter to his hotel and see him checking in: the clerk specifies that he’ll be with them for specifically ‘thirty-six hours’. Noted, though an odd thing for anyone to say, and perhaps a clue on the calibre of the script, as much as what is to follow. For when he reaches his room, he’s greeted by a dominatrix, Mistress Satana (Jen Soska) who immediately holds forth on what a dreadful man he is, as well as getting started on the whole whips and chains stuff. Strangely, Peter seems genuinely bewildered by at least the beginnings of this ordeal; fair enough, we all sometimes pay for things we forget about.

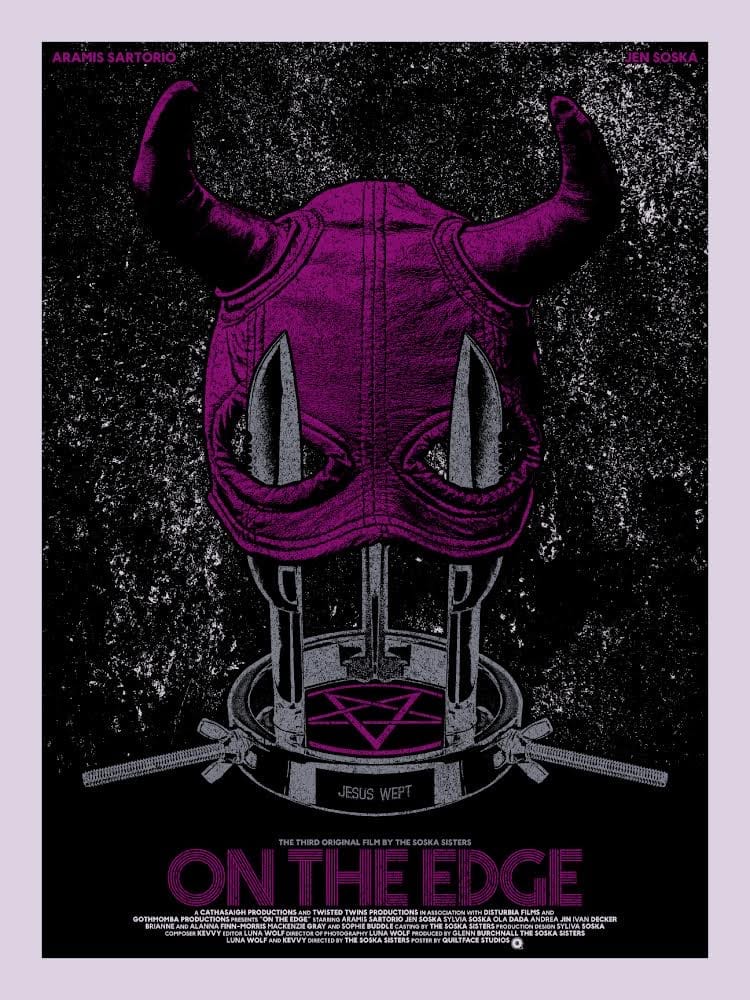

Next: the film unleashes what I’m sure is meant to be deeply shocking footage of genital torture and the prone male body, albeit that you may have seen something very similar in, say, the godawful Neighbor (2009) – before the most graphic scenes were cut for UK audiences, anyway. In fact, if you survived the torture porn years, there’s little in this particular torture porn which will unsettle you. So, assuming shock value is out; what’s in? Not much, not much. There are long, long lulls throughout; lines of dialogue and scenes which repeat (“Let me out! Let me out!” etc) and – about an hour or so in – some theological/mythological plot additions, there to insinuate that there is far more to this than merkins, verbal abuse and various things being shoved up Peter’s jacksie. Yes, this is Peter’s dark night of the soul in more ways than one, and so across nearly two hours things cross into more surreal fare, with the whole ‘demons of conscience’ shtick taking over for the rest of the film’s duration.

And yet, just as the whole tied-to-chair thing had its day some time ago, so the whole surreal introspective nightmare has been done better elsewhere, too. But that aside, segueing from physical torment to existential drama offers zero excuse for the production values here: roughly edited, poorly lit and lacking impetus, the whole film comes overlaid with All The Musical Genres as a loud, clumsy accompanying soundtrack, easily drowning out most of the dialogue, as the audio here is atrocious – echoey, unclear and uneven. But when you can hear what’s being said, it contributes little of meaning anyway. The nagging suspicion here is that the whole idea behind the film started loosely with how subversive it would be to have a ‘strong female character’ reclaiming her sexuality by being in a position of power – something like that. Miss that memo, and what you have here is a film where you are mostly getting an ass-eye view, with little script, muddy audio, jarring music and a lacklustre plot. It’s as fragmentary as you’d expect.

An additional challenge here is this: it feels impossible to critique any Soska film without – to a greater or lesser extent – critiquing the Soskas themselves. But the particular way in which they, as people, blur into their projects is what makes this so tricky. Where they write, direct and inevitably appear (rarely deviating from ‘the badass’ or ‘the sexpot’) then creative priorities must come into question; is straightforward vanity at play here? In On The Edge, they also have a hand in the production design, the sets, the casting, some of the sound design. Where a film is flawed, this deeply flawed, these flaws keep on finding their ways back to them and how they chose to make that film. And it’s hard not to ponder the trajectory their careers have taken, as the sizeable momentum generated by American Mary (2012) largely dissipated and has instead found outlet in a number of smaller, and/or fewer original projects. Rabid (2019) was, for this reviewer, a rather hopeful sign of better to come. I’ve been watching their films for well over a decade; I’d genuinely like to like a new one.

Of course, it’s tough to get films made out there, particularly post-pandemic. Times are tough and getting a project off the ground, let alone completed, takes some determination. But it seems that the best outcomes for the Soskas are where there are other people involved to say ‘No,’ ‘What for?’ and ‘Are you insane?’ from time to time. Clearly, no one uttered those golden words on the set of On The Edge; the results are there to see. Maybe next time?

On The Edge (2022) received its world premiere at FrightFest Halloween 2022 and recently featured at Monster Fest in Melbourne.