“What am I doing here?” – it’s a simple line, but this early line in Nocturna: Side A sums up the terror and disorientation of old age, particularly when old age is accompanied by dementia – something which the film excels at. When you are losing even the merest anchors of your identity, right down to the reason why you are stood in your own hallway on a particular day, then that is – without a doubt – true horror. The film offers up a terror of – and respect for – the vulnerability of old age, its recriminations and regrets, and it finds varied and unsettling ways to explore a ‘dark night of the soul’. This really is a staggering film, which left me inconsolable at certain points.

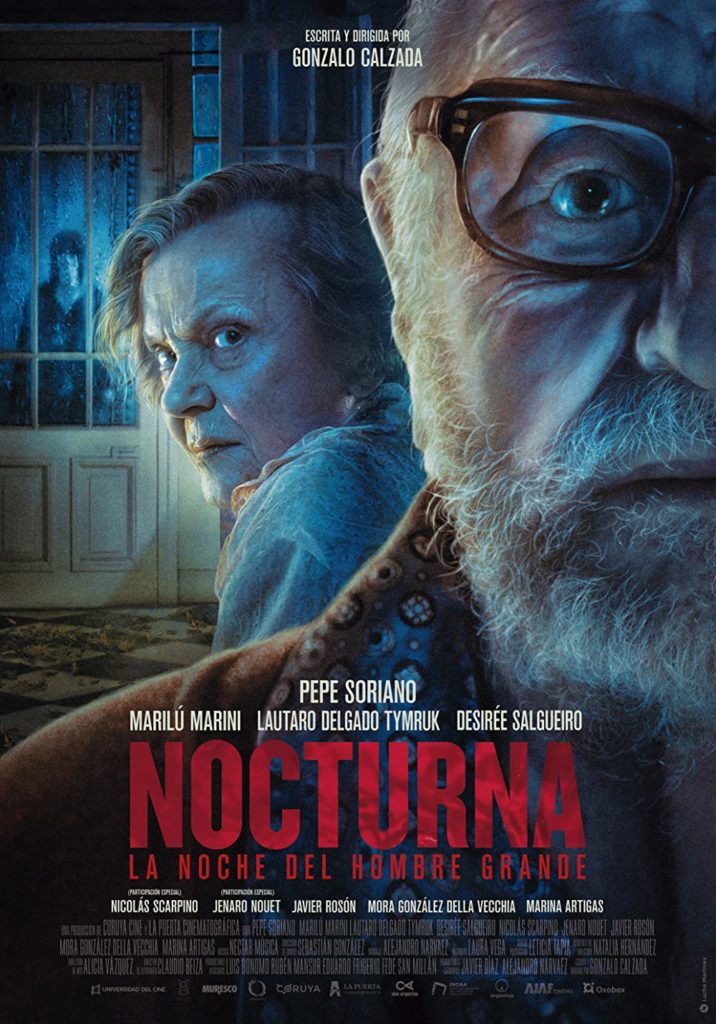

From the moment the film starts, then, particularly where it conflates the young boy with the old man, this film is minutely focused on the plight of an elderly man, Ulises (Pepe Soriano) – in his nineties, and now struggling with the details of the everyday. The sense of sadness and empathy is somehow immediate, the strained patience of his neighbour/superintendent self-evident when Daniel (Lautaro Delgrado) finds Ulises, dumbfounded, outside his door. The older man makes his way back to the apartment without the groceries he set out to get; his wife, Dalia (Marilú Marini) is irritated with him, but forgets this particular irritation to focus on a greater worry: that their days in the block are numbered, and that the housing association is going to find a way to get rid of them; they ‘don’t want old people there’. On a similar note, they both live in fear of intruders, thieves, anyone forcing their way into their home, a home which is their whole world. The world grows very small when you are elderly.

Both of these people are frustrated with their lot, but Ulises differs from his wife because he feels he has more left to do – he wants to live, he wants to put things right in the limited time he has remaining to him. He mentions an estranged daughter and grandchild; the memory of them reinvigorates him, but Dalia is scornful of them, and of him. However, for all this, it seems that their fears of their home being infiltrated by outsiders may be coming true when, in the early hours of the morning, there is a noise outside. Then someone begins hammering at their apartment door, claiming to be a neighbour in need. Ulises tries to handle this situation, but he can scarcely keep it together – he quickly grows anxious and confused. The whole thing becomes an ordeal, but as it unfolds, it reveals far more: what is real? Who can be trusted?

The relationship between Ulises and Dalia and the outside world is a sad, fractious and often frightening one: their anxieties impinge more and more upon their small sphere, and drive a wedge between them at times, too. But, in following Ulises closest of all, the film in some aspects reminds me of Death of a Salesman. Although Ulises is far older than Willy Loman from the Arthur Miller play, the sheer relatable nature of the tragedy of an everyday man, struggling with hallucinations and flashbacks as he reflects on his errors – the standard of observation is similarly acute, and the emotional weight is huge too. However, the growing emphasis on pure fright, with possible supernatural elements introduced, adds a particular, different colour to the pathos being generated. Ulises’ uncertainty and his inability to cope with someone trying to batter their way into his home reminded me strongly of my own grandmother who, as dementia took her, repeatedly claimed that someone was trying to break into her house. It frightened her but we brushed it off. Forgive the personal detail – this just feels like a deeply personal film, which I hope excuses it – but the film made me understand her anguish in a different way, and as such it’s quite the emotional gut-punch, and rightly so. It is scary.

The film retains its meticulous eye for the personal impact of ageing and dementia throughout; it’s unflinching, but it’s tender, and it achieves this from the very beginning with even the easiest moves (the close focus on Ulises’ face for example, and Soriano’s effortless performance, is enough to generate empathy). In a genre-busting piece of work, it also includes the great frustrations that ageing can cause to everyone affected. It can be maddening and frustrating – but making a humane film means you have to be honest about everything which makes us human. The film can be difficult to bear, it’s an agonising watch, and the addition of scares only underlines that, with an added complication to bring to bear on the key players.

Nocturna Side A is phenomenal, and certainly one of the greatest I have seen on this topic (if I may, I’d also recommend the short film ‘Ark’ by Grzegorz Jonkajtys; it’s another heartbreaker). Whilst it could absolutely stand alone, it forms part of a double bill: Nocturna B is being released alongside the first. As for Nocturna Side A, it is very definitely a recommended film, if with the proviso that it packs an unprecedented emotional punch.

Nocturna Side B: Where The Elephants Go To Die is, though, an oddity – one which doesn’t work except as an experimental shadow of the first film; it’s definitely no standalone. It covers the same timeframe as Side A, though taking a rather art-house approach to the characters and themes, revisiting them through a highly-edited and filtered array of alternative perspectives: shots zoom, frames jump, scenes repeat. A voiceover addresses many of the by-now recognisable themes, albeit it in quite abstract language (which is, dare I say, rather lofty, with a lot of hyperbole and platitudes). There’s a possibility that, given the sheer amount of voiceover used in Side B, some things have been lost in translation, which perhaps has an impact on how significant all of this feels. It’s not an unattractive film, but it’s a strange film, and it has none of the power or pathos of the first – its existence is a curiosity, all told. However, anyone wishing to observe the events of the first film refracted through a very different style and approach may find something to love here. For the rest of us, Nocturna Side A neither gains nor loses anything through the presence of the second part, and it’s Side A which deserves all the praise.

Nocturna Side A: The Great Old Man’s Night and Nocturna Side B: Where The Elephants Go To Die are available on digital from 18th January 2022 with The Nocturna Collection released on February 1st.