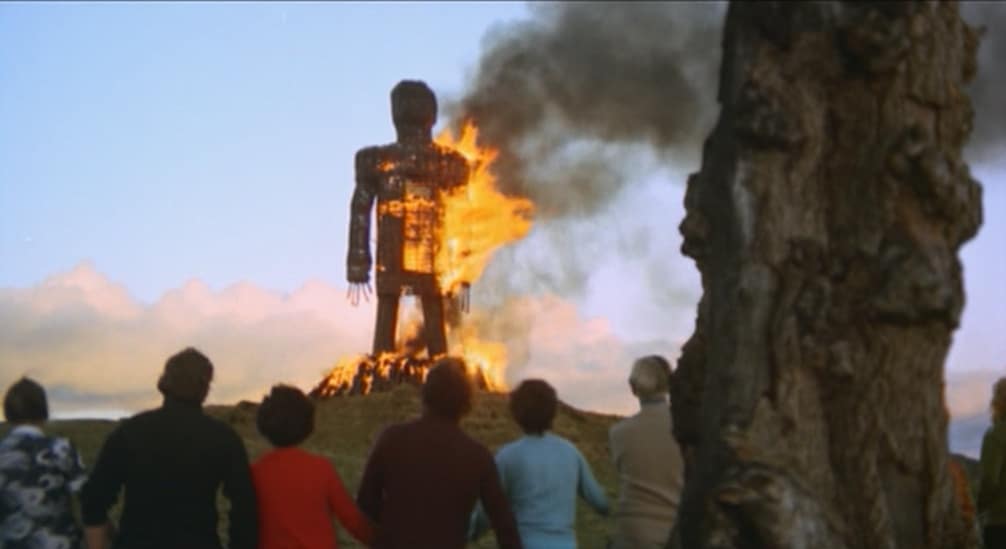

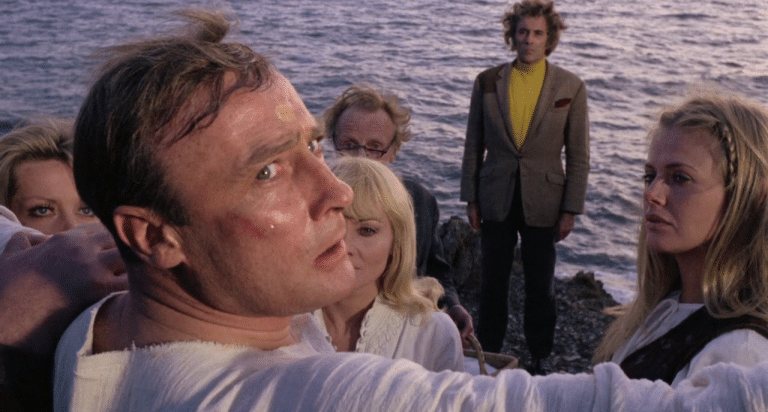

The Wicker Man (1973) continues to hold its place as one of the best-beloved British horror films of the past fifty years, with new viewers and fans emerging as the years pass. This speaks to its many strengths, and the way in which it works on many levels, offering the potential for new readings and responses from new viewers as well as its existing fans. As such, Robert J. E. Simpson’s charming, well-informed and engaging monograph on the title has a great deal to offer and makes for an interesting, thought-provoking read. As a long-time fan of The Wicker Man, it certainly gave me new ideas and ways to interpret.

The book has an interesting pedigree – as explained in the introduction – whereby it started life as an academic project but then, for a number of reasons, ended up on the back burner for a period of some years. Finally completed when the pandemic landed us all with rather more time that we would have had, the book occupies a somewhat liminal position between academic writing and the pleasure of writing about a film which is clearly dear to the author. There’s always a danger with academic writing that researchers focus so closely on the component parts of whatever they’re studying, they lose sight of the sum of those parts. In other words, they stop enjoying the film as a piece of entertainment, which always shows in the writing. That isn’t the case here, and although academic ideas are brought to bear on the film (for instance, Roland Barthes and the relationships between visuals, music and text) these are always kept accessible, footnoted and most importantly, blended carefully with the overall considered, but warm and enthusiastic tone of the text. This helps the more academic, ‘meta’ type ideas to really land; there’s no danger of the text turning into something abstract, too far removed from a fan’s perspective on the film.

When I say the film, of course the book is largely focused on the ’73 original, but it also draws some interesting comparisons with the much-maligned remake of 2006 and also looks at the perplexing ‘sequel of sorts’, or else extension of the Wicker Man universe, The Wicker Tree (2011). This is all handled fairly, though the author largely seems to reflect positively on the greater subtleties of the 1973 film as a result – again, which seems fair.

The Willing Fool is also structured in an interesting way, rather than with the more conventional description, information on casting and so on before moving into a closer study of the film; it is organised, in keeping with its avowed focus on the spectacle of The Wicker Man, by symbol, visual focus, character, specific settings and frameworks (such as the ‘documentary’ claims in the introduction). It’s an approach which works well, an intuitive style which breaks the spell of the expected, formulaic standpoint used in film writing. In this respect the book emulates what it identifies in the film itself, in its disruption of a conventional, distanced, separate approach from the Wicker Man narrative. It’s also a positive, all told, that whilst the book takes in ideas about folkloric precedents, it doesn’t simply take a ‘folk horror’ approach. The rise and rise of folk horror as a discipline has led to some fine writing, but it needn’t replace other ways of seeing, or speak for them all. (Film credits, an article on The Fantasist and an interview with director Robin Hardy are included in the appendix).

Coming in at just over 120 pages, this is a slim illustrated volume, well-focused with just the right level of range and detail. Even for those who may have pored over The Wicker Man a hundred times, there will be information and critique here which will be of interest. Full disclosure: I have worked with Robert Simpson over the years, but that changes nothing about this recommendation! You can check out ways to purchase The Willing Fool here.