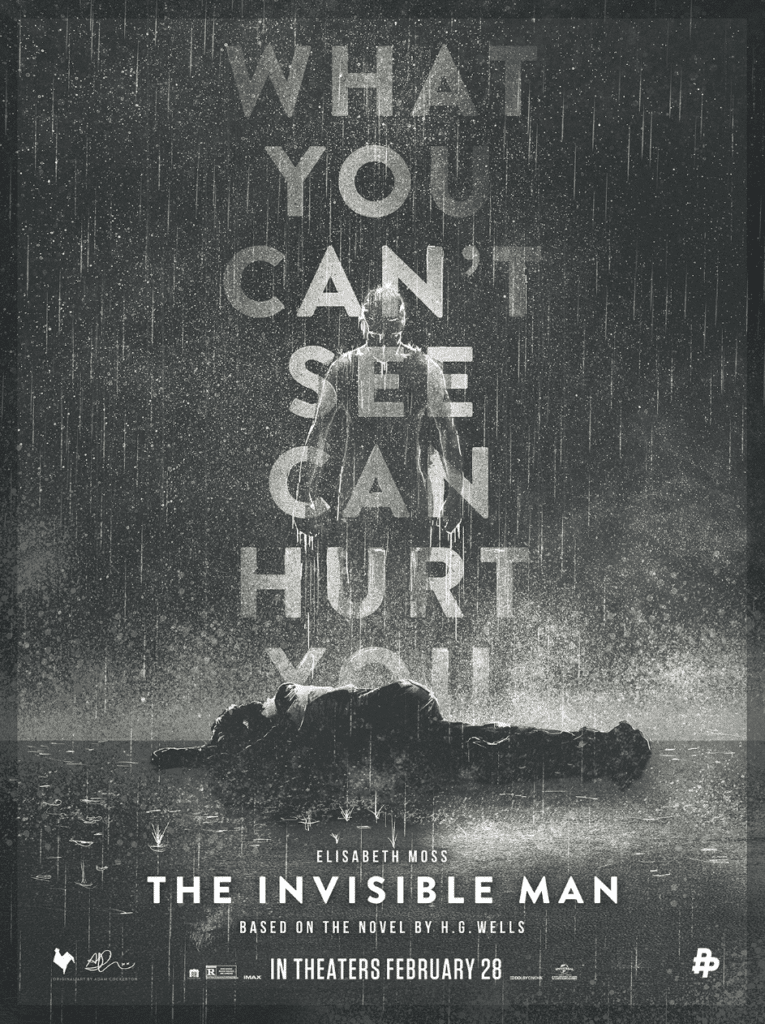

At last, we have up-to-date evidence that it’s perfectly possible to make a new version of a classic story that neither tinkers unnecessarily, nor departs entirely from the tone and content which made the story so good in the first place. Leigh Whannell’s take on the H G Wells story of The Invisible Man retains the paranoia and uncertainty which runs through the 1897 tale, and certainly keeps the spite and unreason of the invisible antagonist, but by re-positioning it in the 21st Century and exploring an all-too-real subject via its central conceit, the result is an intense, fraught and almost panic-inducing story. I’m recommending it, with the proviso that the level of stress it caused was at times quite unbearable.

Cecilia (Elisabeth Moss) has all of the outward appearance of wealth and comfort, one of many, many disruptions which the film offers up from the earliest scenes. It is quickly revealed to be a gilded cage, and she is planning to leave her partner, Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen); that this needs to take place in the early hours, after drugging him, tells us neatly that he is someone to be feared. She successfully gets out after the film’s first watch-through-hands sequence, hitching a pre-arranged lift with her sister to a safe house, the home of her friend James (Aldis Lodge) but the impact of her trauma upon her has been extreme. She is damaged; she fears that Adrian will come for her, and she is too scared to leave the house.

Perversely, news of Adrian’s suicide a few days later offers Cecilia the chance to start rebuilding her life; so successfully does Moss enact being a deeply damaged abuse sufferer, that you can have no qualms about celebrating the relief she so clearly feels at the news that Adrian cannot hurt her again. Remembering her in his will, Adrian leaves her the proceeds of his lucrative specialism in optics, but there are conditions, as stipulated by his brother Tom – the nominated executor of his estate. If these things seem too good to be true, then truly, they are. Cecilia begins to hear things, see things which do not make sense. She interprets this as showing that in some as-yet inexplicable way Adrian has not left her; her loved ones interpret this as evidence that she is struggling to cope. The evidence begins to mount: just enough to make her doubt her own mind at first, the silent, mounting assaults on her strengthen and change, soon impacting upon others around her.

Cecilia’s battle to make people believe what she is telling them is, again, testament to Elisabeth Moss’s performance throughout this film; in less capable hands, a woman deliberating on or indeed struggling with an unseen assailant could be utterly flat, even laughable, but it’s not so here. Essentially acting her way through a sci-fi spin on gaslighting, she is deeply sympathetic and plausible, and the decision to frame this as a woman leaving a partner – and what that partner is willing to do to punish this ‘crime’ – is an inspired one. That said, anyone who has been in an abusive relationship, go forewarned; this is not easy viewing. The means may be extraordinary, but the behaviour (and the fallout) is disturbingly feasible.

Whannell takes other interesting decisions along the way, and another aspect of the film which worked very well was in what it doesn’t do; the audience is invited to become as uncertain as Cecilia. The camera will pan around and hold on a scene in which nothing is happening; whether or not someone is there, we cannot know. It’s also intriguing that Whannell dispenses with the original story’s garrulous invisible man, where Griffin narrates his own story, makes requests, makes threats and ultimately holds sway over his unwitting host via language. In 2020, our invisible man is almost mute. This adds a great deal to the sense of risk, of never ‘knowing’ what is there. Layered over all of this is an incredible, ominous Benjamin Wallfisch score whereby the music suggests threats which happen – or don’t. Aurally similar to some of his work on Blade Runner 2049, the heavy, atonal soundscape is absolutely integral in the design of all this tension.

The Invisible Man shows us a person being broken down into component parts, before, slowly, composing herself from scratch. Not everyone will enjoy the redemptive moments but, for my part, I thought it all worked well, a needed leveller after an almost unendurable, escalating sense of threat and powerlessness. It’s absolutely the best thing Whannell has ever done.