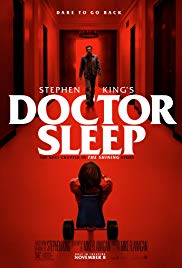

When Mike Flanagan and his creative partners stepped into horror cinema’s big time with the announcement of their adaptation of Doctor Sleep, they were assuming responsibility for one of the most eagerly anticipated sequels in modern cinema. Widely (if not necessarily universally) heralded as a classic, Kubrick’s The Shining is an established treasure trove of modern cinematic iconography, casting its brooding shadow since its release in 1980. With such an atmosphere, and so many scenes, lines and photographic stills firmly embedded within the contemporary consciousness, any sequel would have plenty to live up to in order to be regarded as ‘worthy’. Factor in too, that Doctor Sleep is not ‘just’ a film sequel but also a literary one, its author ‘Master Of Horror’ Stephen King – and suddenly the hordes waiting with baited breath are swollen in number by those who are invested in Kubrick’s vision, to those who, as they say ‘preferred the book.’

Happily, for fans of both iterations, stewardship of the storytelling universe centred upon the Overlook Hotel could hardly be in safer hands. Mike Flanagan, along with principle collaborators such as producer Trevor Macy and cinematographer Michael Fimognari, has in recent years established a body of work that has skilfully woven an appreciation of horror’s classic tropes with a thread of contemporary relevance, in keeping with the demands of a modern reading that looks for a certain degree of humanism at the heart of its central premise. So, for haunted houses, haunted dreams, haunted objects and urban monsters, we have interconnected wider themes of family, negative forces and how they can be passed from locations to persons, from person to person and thus from generation to generation. Also, how these negative forces may originate from human agency but can also be nullified by the right kind of human interference. Crucially, the depiction of these distinctly human themes do not come at the cost of atmosphere or scares.

Another notable factor is the patronage of King, who praised not only the adaptation of his novel Gerald’s Game but also Flanagan’s most noteworthy success to date, Netflix horror The Haunting Of Hill House, itself adapted from Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel. If nothing else, this thumbs-up from the author should surely embolden Flanagan and co to carry on interpreting King’s writing with confidence. Also, for those who grew up as fans of the King literature ahead of the Kubrick cinema, any doubts they may have harboured about their hero’s work being misinterpreted would surely be dispelled by such a vote of approval.

So much for the hype…what about the film itself? If anyone who watched the remake of King’s IT like me baulked at the almost instant use of blood and violence as poor Georgie has his arms ripped off by gutter-haunting clown Pennywise, rest assured there is a greater degree of subtlety employed in the opening scenes of Doctor Sleep. We are at first introduced to The True Knot, a sinister group whose lives are made unnaturally long through predation upon young people who exhibit various powers of Shining. More than simply feeding upon them, it is in fact necessary to ensure that they die in as much agony as possible, for the greater the pain inflicted, the greater the purity of the essence (or ‘steam’) released during their dying moments. The de facto leader of this group is the charismatic Rose the Hat, who, alongside her lover Crow Daddy, decide whether to harvest their victims there and then, turn them into one of their own, or eke out their suffering (and their precious steam) over as long a time as possible. This vampiric tribe exists in a state of nomadic hunger, searching it seems ever farther and wider for the once plentiful supply of children with Shining who seem to be ever rarer, their Shine more and more diluted by modernity.

In the same timeframe as we discover the Knot, we also reacquaint ourselves with young Danny Torrance and his mother Wendy, shortly after the events of The Shining. They now live in Florida, but as far removed as they appear to be from the mountain fortress of the Overlook, the rapacious revenants of that place still haunt young Danny. He is shown a way to harness his power to rid himself of these shades and their seemingly ceaseless quest for his life, as he is visited once more by the ghost of kindly fellow-Shiner Dick Halloran (memorably played by Scatman Crothers in The Shining). Fast-forward to 2011 though, and it seems that for all he was taught to defeat the ghosts of his past, nothing suppresses the disturbing visions inherent with the Shining like alcohol, drugs and cheap sex. Dan, as he is now known, lives by at once drowning his past and racing toward an inevitably bleak future. He receives another visit from his old protector Halloran, who tries to turn him away from his path of self-destruction.

Dan is forced to travel far and wide, to try to run away from himself, as far from the destruction and horror of his past as possible. Finally, he washes up in a small town where he is accepted by a kindly local, a man who seems to recognise the roots of the fragility in Dan’s eyes. Discovering support and employment, he finds the courage to put down the bottle and begins to forge a new life. As the previously suppressed Shining returns in strength, so he finds a way to use the power he has as a force for good, ushering the dying patients of the hospice he works at across the threshold from life to death, in peace, unafraid. In so doing, he finally comes to live up to his old nickname ‘Doc.’

Another consequence of his returning powers of the Shining is a strange friendship with another who shines, who begins to leave messages scrawled on the wall of Dan’s room. Young Abra Stone is aware of her ‘magical’ abilities, much to the bemusement of her parents, who refuse to talk about it and so force Abra to reach out into the world using her powers, looking for understanding. Sensitive to those who use the Shining and herself acting as a beacon for those who are also sensitive, inevitably she comes into contact with Rose and The Knot, their own search for sustenance these days growing increasingly desperate. In this way, the stories of Dan, Abra and Rose begin to converge. The stage is now set for a battle of astral projection, the hunter becoming the hunted, and the inexorable pull of the past and its demons upon Dan…

On many levels, Doctor Sleep is a story in which the past, in its brooding, dogged way, must be conquered or at least reconciled, in order to defeat both its hungry ghosts and its multifarious consequences – tendrils that reach out as if in pursuit, only to be found waiting exactly where they came from, all along. Danny Torrance must therefore come full circle in his journey, returning to the place he has spent so long trying to escape from, whether with some magical trick taught to him by Dick Halloran, or by turning to drugs, drink and violence much as his father once tried to do. In the end, although he spends his life running ‘from himself’, as he puts it, the absurdity of trying to do so is made apparent when he decides, in his desperation, to head for the old hotel once more.

For the makers of this sequel-of-sorts, reconciling the past and the future to create a cogent resolution to the 42-year old cycle started by King’s 1977 novel, similarly meant finding a way to step from beneath the looming shadows of giants. Flanagan and co wisely choose to embrace those shadows, and as such everything in Doctor Sleep is cast in much the same hue as The Shining. Pacing and score contribute to the heavy sense of foreboding, and much weight is given to the Kubrick contribution to the story. The scenes in the Overlook itself are faithfully recreated, waves of blood and all, as if to emphasise the timeless waiting presence of the place. The comparison with Hill House is an obvious one – both buildings conceal a patient yet ravening hunger behind their grand facades; both are homes to ghosts who crave the succour of living souls. Both Hill House and the Overlook Hotel pursue their quest for souls via the agency of family, of blood ties that are so strong as to bind against madness. Families that can be so catastrophically inverted by the corruption of a parent or parents against their children.

By choosing to integrate The Shining and Doctor Sleep, rather than reframe or reinvent the former to suit the latter, a strong element of continuity is preserved. This attention to detail is followed meticulously, such as with the cameo performances of Alex Essoe and Henry Thomas as Wendy and Jack Torrance, as well as the visual elements of the Overlook. Whether The Shining was a film in need of a sequel is perhaps arguable, but having decided to tell the story of what happened to Danny Torrance, Stephen King could hardly have hoped for a more sympathetic or diligent team to bridge the gap of years. The casting is excellent all round. Ewen McGregor is easy to sympathise with as Dan, his fragility and basic goodness as a person shine (ahem) through, as much as Rebecca Ferguson’s witchy Rose is cold and unknowable. Kyleigh Curran is likeable as the surprisingly confident Abra Stone, even if her almost happy-go-lucky performance is slightly at odds with the sense of imminent threat that pervades throughout. Support from Cliff Curtis and Zahn McClarnon is also standout.

All told, Mike Flanagan has taken what might at first appear to be a daunting and thankless task – producing a follow up to a cinematic classic 40 years down the line – and made of it about as successful an attempt as anyone could do, given the various demands of those various factions invested in it; be they King fans, Kubrick fans or book-over-film fans and so on. True to his style, humans themselves are not portrayed as wholly evil or wholly good – rather they are able to become corrupted all too easily; by drink, by their lusts, by the nameless power resident in an old hotel. In one of the most affecting scenes, Dan stands up in an AA meeting, ‘eight years sober’ chip in hand. He recounts the tale of his father, who he only really knew when the darkness of drink and violence descended upon him. There was a time, he says, when his father tried to embark upon his own recovery and would have wanted nothing more than to stand where his son proudly stood that day, eight years sober. In this way the humanity of Jack Torrance is reclaimed, after 40 years as a virtual comic book villain.

It is this power to ‘reclaim’ the traditional ghost story or horror film from the ignominy of mere shlock entertainment that has made the work of Mike Flanagan so effective, but this is not merely a case of watering down the essential darkness at the heart of the best horror. There are plenty of chilling moments; in particular the Knot’s ghoulish pursuit of children with the Shine produces some grisly scenes. Having already whetted their blade upon Hill House, the Overlook is of course milked for all it’s worth. There is a certain degree of satisfaction as we return there to the ominous strains of Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind’s original, hauntological score. Whether you will feel equally as satisfied upon the film’s resolution is your choice – for me it felt like as suitable a way for the story to resolve itself as any other. Well-acted characters who are easy to care for or dislike, a heavy atmosphere of inevitable, looming dread, and plenty of ‘Easter eggs’ for those who look out for such things. Perhaps the greatest compliment you can give Mike Flanagan is that he took the work of King, Kubrick et al, and made it part of his own, increasingly recognisable storytelling universe.