Remember the seventies and eighties, when regular moral panics about popular films, music, television shows and finally, videos were the thing? When the Tipper Gores and Mary Whitehouses of this world would insist, without a scrap of real evidence, that various media were responsible for acts of moral depravity and horrific violence? This argument has emerged regularly, as again with the rise of video games as a convenient scapegoat for the acts of damaged individuals, often wheeled out confidently by the gutter press and politicians as a primary cause of complex crimes before the facts of the case are even in.

In 2019, we find ourselves at another cultural moment where mainstream entertainment is accused of inciting crime and this time it seems to be the media at large, and more shockingly, film critics themselves, who are pushing this narrative. The latest film in the critics’ crosshairs for allegedly promoting violence and masculinity of the (buzzword klaxon!) ‘toxic’ variety is Todd Phillip’s Joker. The run up to the release of the film included warnings based on absolutely no evidence that it may somehow spark the new media bogeymen – the alleged ‘incels’ – to take to the streets with their personal arsenals and wreak havoc, on the grounds that such people really exist in grand droves, are inherently violent and murderous, and all they need is the correct encouragement by a mainstream picture to get busy.

As it is, a few weeks into release, Joker currently has a body count of zero, and a box office take ($600million – a massive success given its $70million budget) that suggests an awful lot of people have seen it, which perhaps should tell us all something about what world critics are currently inhabiting – an entirely separate one to paying audiences, it seems. This also seems reflected by the current vast division of opinion between audience and critics on sites like Rotten Tomatoes – a divisiveness that didn’t begin with Joker and surely will not end with it.

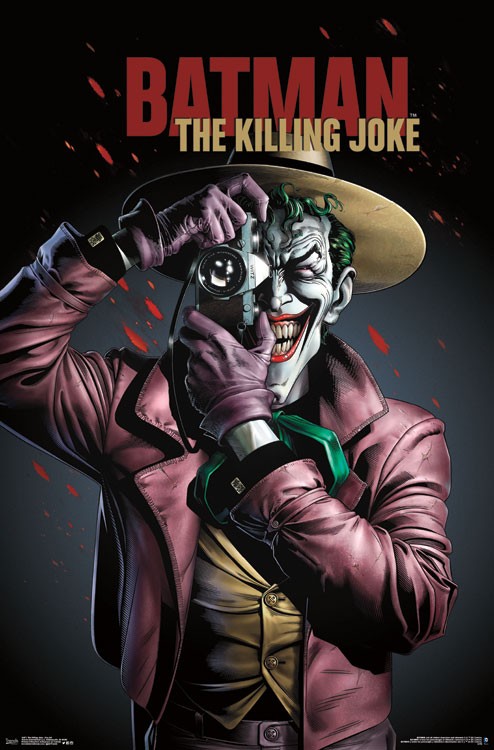

Joker is a very interesting take on the comic book; the film blends the premise of Alan Moore’s acclaimed one-shot Joker origin story The Killing Joke – the Joker as failing stand-up comedian – with a narrative and visual love letter to an era of film with which many younger filmgoers today will be sadly unfamiliar – the seventies to early eighties. This was an age of films mired in the seedy, darker side of American life, often exploring the criminal fringes of society, the put-upon working class and the travails and existential angst of the average man or woman trying to get by in a society awash with crime and corruption. Conventional heroic attributes were thin on the ground. It’s all a hell of a long way away from the colourful, PG-rated, superhero fantasy tentpole popcorn pictures that have dominated the mainstream cinema landscape for the past ten years.

The seventies to early eighties was an era of cinema that reflected the changes in modern society of the time, political upheavals as well as the sexual revolution. It centred on society’s rebels – with or without a cause – and anti-heroes; flawed, morally struggling or simply increasingly unhinged characters, played with relentless intensity and Method-style commitment by rising stars such as Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. They were unrelentingly gritty, often unsettling and dark-natured films, nothing that anybody could ever describe as ‘feelgood’. Think Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, Silkwood, Scarface, Midnight Cowboy, The Deer Hunter, Raging Bull, and in particular the relatively little known De Niro vehicle and 1982 box office flop, The King of Comedy, which alongside 1974’s Taxi Driver, 2019’s Joker owes a huge narrative and visual debt. These were and remain films for adults, not for children, and they existed at a time when cinema attendance was at an all-time low whilst cinemas were falling into disrepair alongside ailing economies. This all started to change with the rise of the blockbuster film, the family-friendly, FX laden spectacular that drew in repeat viewers of all ages, beginning with Star Wars in 1977. Combined with clever toy merchandising, this trend financially reinvigorated and eventually came to dominate the business and redefine its target market, but the era is still cinematically defined by the gritty, adult-oriented works of Martin Scorsese and the intense performances of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, among others.

Joker is set in the same era as all this cultural and political fracturing – and veers so far away from the safe, family-friendly, entirely self-referential ‘universe’ now associated with the comic book genre that many critics seem to forget what Joker still is, and what it is not. Despite its adult nature and feints at digging into the social upheaval of the times, Joker is primarily a comic book movie. It is an origin story of one of the most well-known comic book villains in the genre’s history. It is not an instruction manual. It is not a political manifesto. It is also something missing from the comic book genre since Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy – a comic book film as the particular and peculiar vision of a single filmmaker – Todd Phillips – in this case, a vision informed by the work of another singular filmmaker, Martin Scorsese. Indeed, Scorsese was involved with the production in its early stages.

Part of what allowed for such a singular vision is that fact that Joker was conceived and shot as a stand-alone film rather than the beginning of a franchise, freeing it from the pressure of setting up a sequence of films down the line, instead of just getting on with a story and telling it well. The story of the Joker as the victim of random violence, familial neglect and abuse, fatherlessness and grand systemic failures, as well as his own peculiarly odd psychology and poor decision-making, it is emphatically an adult film, just as Moore’s The Killing Joke is an adult comic book. While highly entertaining and well-paced, it asks more of the viewer than simply to sit and let the pretty colours wash all over them. It requires some attention and a little bit of thought. It relies, staggeringly in this day and age, on an emotionally and physically visceral central performance by Joaquin Phoenix rather than large-scale explosions of pixels, and that thing that seems missing from so many high budget properties these days: a strong script. It seems as far away from filmmaking by corporate committee and green screen as the fantasy and clearly-delineated heroes/villains of Lucas’s Star Wars universe were from the mentally-ill veteran Travis Bickle and the mean, dirty streets of 1970s New York in Taxi Driver.

Joker presents an origin story, the all-important part of any comic book character’s mythos. It is not, and this is where we suddenly find ourselves in Gore/Whitehouse territory according to parts of the mainstream media who should know better, a call to arms for the disaffected to don clown masks and commit mass shootings. It is still the story of the creation of the arch villain of the Gotham mythos, the psychological terrorist named Joker – the nemesis of and inverse of Gotham’s Batman. Where both experience massive trauma, filthy rich and well-loved Bruce Wayne turns to a pathological fixation with law and order and the creation of a masked alter-ego to effect this, while Joker posits that poor, neglected from childhood Arthur Fleck becomes the ultimate nihilist whose early experiences and constant physical brutalisation lead him to the conclusion that life itself is a joke, and a black one at that. Clown make-up follows naturally, given his former profession as a party clown. Both seek empowerment as their backgrounds, psychologies and resources shape and allow them, for good or for ill. The suggestion that audiences so lack a moral compass or ability to separate art from reality they will be persuaded the Joker’s way is the best way and from thereon wreak havoc, seems implausible at best.

Phoenix’s performance is incredible throughout, an absolute tour de force ranging from a tragically vulnerable and sympathetic adult, to his final, utterly deranged moments of terror theatre. His physical performance; his tics, twitches, subtle mood shifts and swings, his physical fraility (Phoenix lost a lot of weight for the role), his odd, comical clown-shoed walk, his almost Jame Gumb-esque effeminate affect at various points to his final flowering into violence and self-assured villain with a nothing-to-lose swagger, dominates every scene. The entire film is shot from Arthur Fleck’s highly unreliable point of view, allowing him to mislead us at several points as to what has occured in reality as opposed to his fervent, demented dreamworld. Some scenes are instantly recognisable as fantasy, as when he imagines himself being pulled from the audience and hugged by his chat show hero and what appears to be the father figure of his imagination, Murray Franklin, played by Robert De Niro. Another imagined moment, more believably, pivots on the primal relationship between fighting and sex after the Joker’s first kill.

Philips’s script draws heavily from the narrative of Martin Scorsese’s 1982 film The King of Comedy, a meditation on the obsession with fame and celebrity in American culture which centres on a mentally unstable stand-up comedian (Robert De Niro) obsessed with a TV host (Jerry Lewis) who commits a crime in an attempt to manipulate himself into the television spotlight for just one night, come what may. His rationale for this is ‘Better to live one night as a king than a schmuck for eternity’ and this seems to function as the central motivation that the unstable Arthur Fleck finally seizes upon, after a sequence of unfortunate events lead to him killing in self-defence. Indeed, De Niro takes on the role of a very similar talk show host in Joker that his own character was fixated on in The King of Comedy and the film’s final scenes set in a TV studio echoes some of the final scenes of The King Of Comedy. Other sequences seem to draw on Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, particularly the sequences of Bickle’s breakdown. One may even spot a touch of Sidney Lumet’s classic Network in there at points, swirling around the themes of the power of television, suicide and celebrity. Mad as hell, and not going to take it anymore – the rallying cry of the maddened TV host in 1974’s Network – seems to be the mood in the 70s Gotham Arthur Fleck inhabits; it’s a tinder box of poverty, decay and corruption waiting for the fateful spark to set the whole place aflame. Fleck’s Joker is less a leader than someone whose image and criminal acts the already inflamed mob seizes upon to reflect their own discontent.

Joker is by turns bleakly comical, shockingly violent and oddly touching, and overall is an intoxicating, wild ride of a film that manages the precarious balancing act between psychological reality and comic book excess and between presenting Fleck as both vulnerable and recognisably human, a horrific accident waiting to happen. We know from the start that Fleck falling into permanent alter-ego villainy is the point, so the interesting part is how we get there: this film presents the story in such a new and refreshing way, entirely dependent on abnormal psychology in a way that seems to have struck a chord with contemporary audiences. It is one of the only films in recent times I’ve seen that had the audience stay through the credits, excitedly discussing what they had just seen.

It says a lot about how many modern critics have been trained to think, or at least about the type of copy they are urged to submit for maximum clicks, that they are unable to view a complex and nuanced piece of entertainment as well as a refreshing take on the increasingly safe and stale comic book genre without insulting our intelligence, rushing to moral condemnation over the effects it may have on us – the poor, easily-influenced audience. Mainstream film critics currently seem more and more intent on evaluating all mainstream films as overt or covert political manifestos and issuing a pass/fail not on artistic merit, but depending on which side of the political aisle the manifesto appears to fall. Meanwhile, audiences seem more and more intent on ignoring them and evaluating films on their own terms, or simply for their inherent entertainment value. In which case, long live the audience, and the film critics may be writing themselves into the history books as, well, clowns.