By Matt Harries

If ever there was a horror franchise that elicited an equal sense of both joy and frustration, it is surely the Hellraiser franchise. How many films have managed to nail (sorry) such a heady blend of slasher flick and (to paraphrase Doug Bradley) ‘Gothic Ibsen’? The first film, Hellraiser, established a template that has long seen cult status achieved and a host of sequels spawned, unfortunately with ever diminishing returns. Unsurprisingly it is Hellbound: Hellraiser II, filmed with many of the same cast and crew and featuring the direct involvement of creator Clive Barker as Executive Producer, that of all the sequels best manages to keep intact the atmosphere and artistry of the original.

Hellbound retains a gloriously archaic quality to this day, that of a time capsule imbued with the remnants of old, once potent magick. Creature effects, rudimentary animation and set design – all hampered by budget restrictions imposed by collapsing studios and the like. Concepts on a grand metaphysical scale imperfectly realised by the technology of the time, halfway between the practical effects of the 80s and the nascent era of CGI. The fecundity of Barker’s vision was such that any attempt to capture it within the strictures of the mundane realm of the late Eighties film set was always going to be fraught with imperfections. Yet, it is in many ways these imperfections that makes the first two Hellraiser films so enjoyable, even to this day.

As often happens throughout the various storylines of the franchise, the Lament Configuration itself is at the heart of things. So too with Hellbound, where we begin with the sight of a strangely familiar individual in childlike repose – cross-legged and furrowed of brow – turning the box over in his hands, seeking to unlock its mysteries. His fingers write his desire upon the golden patterns of the box, and soon his workings invoke the familiar dolorous tolling of bells and dimming of light. As the device opens to the tinkling strains of a child’s music box, the hungry eyes of the man peer into it. His curiosity is rewarded with hooked chains, blood and pain. We are taken then into some kind of subterranean dungeon and forced to bear witness to the unmaking of this man and the creation of something else – something with precise lines carved into living flesh and decorated by nails hammered into skull by inhuman tentacular appendages. The entity known as Pinhead is therefore revealed to have origins as a man, while it is also made clear that there is some kind of will behind the enticement of the Lament Configuration, some shadowy being using the puzzle box as a fisherman uses a lure.

Returning to the present day, we are reunited with Kirsty Cotton (Ashley Lawrence), as well as the disastrous state of medical facilities of the era. Waking in a dimly lit and dirty hospital room, still covered in grime, the threat of the Cenobites has understandably left her in a parlous state. However, she is not in any old hospital; no, the lucky girl is attended to by the reassuring presence of one Dr. Philip Channard (Kenneth Graham), who we first see delivering a rather metaphysical-in tone speech, while simultaneously delivering a (live) patient from the contents of her skull. The Doctor’s professional detachment can’t quite disguise a certain special interest in Kirsty’s case, but she is none the wiser and in fact has more than enough to deal with after seeing a bloody message daubed from on the wall of her room by a skinless man she believes to be her father.

As Kirsty literally struggles with her demons, we come to learn more about Channard, who takes an elevator to the subterranean depths beneath the hospital. If you thought the regular patients had cause for complaint, the lower levels seem to have been modelled on a cross between Jack Harker’s asylum in Dracula and Freddie Krueger’s boiler room. Patients in the grips of horrifying psychoses are left to battle their imaginary enemies in squalid padded cells, Channard paying them a visit as if checking on seeds germinating in a potting shed. Still hiding behind the veneer of professional concern, he arranges for delivery of a certain blood-stained mattress from the crime scene of Kirsty’s old house. Meanwhile his assistant Kyle (William Hope), bringing some much needed humanity into proceedings, develops suspicions about Channard and breaks into the Doctor’s home, whereupon he discovers sheaves of paperwork including articles on psychic children, diagrams and sketches of a certain exotically-detailed box and photographs showing the individual we first saw at the very beginning of the film.

Much like Kyle, we the viewers have seen enough to know that Dr. Channard is yet another man driven beyond human morality by insatiable curiosity and thirst for knowledge pertaining to life beyond the earthly realm, beyond death itself. Following on from Frank and Captain Elliot Spencer (he who would become Pinhead), the Doctor’s pursuit of the unholy unknown is like a puzzle itself, comprised of various pieces he assembles and begins to manipulate: knowledge gleaned from his studies of the Lament Configuration, his unfettered access to psychotic patients, a young girl with a preternatural skill for solving puzzles, a certain blood-stained mattress – all these elements he brings together, drawn by the dark force behind everything, the force that unmade Captain Spencer and raised a great demon in his stead.

There were, of course, others before Channard who were drawn inexorably into the machinations of the box. Soon, his bloody experiments have raised one of these individuals back into the earthly realm, namely Julia (Clare Higgins), the woman whose lust for good old Uncle Frank proved just as great as Frank’s own deadly desires in the first film. She provides a crucial facet of the story, that of being a romantic foil for Channard. Naturally enough for a Clive Barker creation, sexual magic is as potent as blood magic and both together are irresistible, especially once the hapless Kyle – always far too nice to be anything other than cannon fodder – falls victim to Julia’s thirst for restorative blood. With the young girl Tiffany working to unlock the Lament Configuration, Channard and his partner in lust seem destined to step into the world beyond.

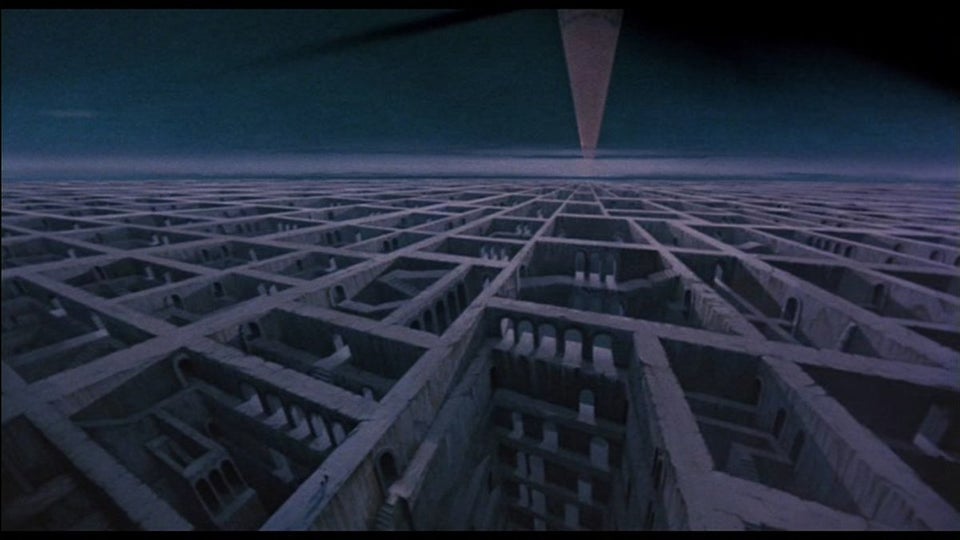

With the rather extensive use of flashback scenes in the first part of the film (perhaps a consequence of the aforementioned financial woes afflicting the production), a fairly coherent narrative is established as the principal characters chart an inevitable course to Hell, the labyrinthine dimension of Leviathan, the great power behind the Lament Configuration. Henceforth, perhaps encouraged by the creative possibilities of a place located beyond the boundaries of our world, things get a little less linear and a touch more chaotic. This state certainly suits the visual concept behind Hell, represented here as a vast Escheresque maze of stone stretching beyond the horizon, shadowed by the monolithic, diamond shaped Leviathan. While you’d be perhaps be forgiven for thinking a visual representation of such a realm would be beyond the set designers of the time, in fact for me they do a pretty good job with the tools at their disposal, in creating a vista in which atmosphere just about manages to outweigh the clunkiness.

Character motivations now become a little harder to discern, as Julia reveals her true purpose, presenting Leviathan with another soul in the shape of her beau Channard, who is then remade as the Doctor Cenobite. This memorable new creature is umbilically connected to Leviathan, empowering the former surgeon with more of the tentacular appendages we saw in the creation of Pinhead at the very beginning. These bizarre appendages, brought to life with a kind of third-rate Harryhausen animation style, are like some kind of Swiss Army knife/worm hybrid – they really have to be seen to be believed – and aren’t in all honesty the most impressive of weapons, at least in terms of appearance.

The Doctor’s charm as a villain lies instead in the way he combines the Cenobite stylings of leather and scarification with remnants of a surgeon’s patter, camply declaring ‘I recommend…amputation!’ among other gems. Whereas Pinhead is a model of icy comportment and moves as though he has all the time in hell, the Cenobite formerly known as Channard is all juddering, malformed laughter and ‘What was on the agenda today? Ah yes, evisceration!’ Certainly he is grotesque and awful, but also quite amusing.

The film tumbles as if hurricane-blown toward its conclusion, all ham-villainy, gore galore, double-crossing and chases down dead-ends. We get to see Uncle Frank in both his vest-sporting and skinless guises, while Julia too learns that borrowed flesh can easily be returned against her will. Leviathan’s great power seems not to extend to omnipotence within its own realm, something I admit to never having a detailed comprehension of, but then again, in examining Hellbound we are asked to turn a bloodied cheek; to the erratic plot, the general campness and the occasionally shonky visual effects.

It may not make a great deal of sense, but in combining the timeless gothic-gore style of the Cenobites with the lust-addled human element – in all its error strewn and shambling incomprehension – Hellbound: Hellraiser II is a worthy successor to the original and certainly worth a watch at 30 years old.