Spoiler warning.

Spoiler warning.

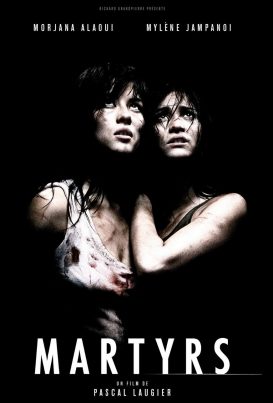

It certainly doesn’t feel like ten years has passed since Pascal Laugier’s divisive horror film Martyrs first arrived, but the more I reflect on the state of horror cinema at the time of its release, the more I feel inclined to agree that ‘the past is a foreign country’. In 2008, horror cinema was still riding high on an often grisly wave of excruciating cruelty. The ‘new wave’ of European horror cinema, alongside US box office dare-fests like the Saw franchise and Hostel, seemed determined to goad audiences by forcing them to be privy to all manner of methodical torments. Not for nothing had the term ‘torture porn’ arisen, albeit not because these films were meant to be titillating, but rather for the camera’s unblinking gaze as it watched these torments occur – often to a prone body literally manacled into position to allow us to get a good, long look, leading to growing frustrations (on this author’s part, at least) with the new tradition of torture-via-chair, albeit that in 2008 this trope was rather newer. It’s also telling that our website’s original incarnation was under the title Brutal as Hell, which says a good deal more about the cinema we covered then than it did when we finally retired the name in favour of the rather broader church of Warped Perspective.

Certainly, I never expected to find myself writing about Martyrs again. My initial, gut reaction to the film was very negative indeed: I saw it as cut-and-shut torture porn with pretensions, a glorified excuse to beat and maim women by adding a glib reference to the meaning of life at the end. However, it’s a film I’ve gone on to watch several times, when I haven’t done that even with films I’ve lauded with praise from the beginning, and on each repeat viewing, I’ve noticed something new, something intriguing. Even if I think a damning indictment of the film can still stand, and even if I can still empathise with that, by ten years on I’ve come to think there’s more to Martyrs – largely because, upon reflection, I think it occupies an interesting space in the development of 21st Century horror.

I reference the ‘cut-and-shut’ idea above because one criticism of Martyrs is how it shifts from the intimation of supernatural horror to something altogether different in its second act, as the film’s supernatural content gets closed off not just to the audience, but also to the people trying to coax supernatural evidence out of their victim. Lucie’s campaign of vengeance (abuse-revenge rather than rape-revenge) is punctuated by visions of a tortured girl rendered almost demonic by her determination to attack Lucie. We are left wondering, at this stage at least, whether Lucie is undergoing a pure hallucination: the gravity of the attacks on her push the idea of this being ‘all in her head’ about as far as they could conceivably go. In this respect, Martyrs seems to draw together a lot of the quite disparate threads which were drifting along together in horror cinema at the time, and it does so in a way which is quite unique and challenging.

I reference the ‘cut-and-shut’ idea above because one criticism of Martyrs is how it shifts from the intimation of supernatural horror to something altogether different in its second act, as the film’s supernatural content gets closed off not just to the audience, but also to the people trying to coax supernatural evidence out of their victim. Lucie’s campaign of vengeance (abuse-revenge rather than rape-revenge) is punctuated by visions of a tortured girl rendered almost demonic by her determination to attack Lucie. We are left wondering, at this stage at least, whether Lucie is undergoing a pure hallucination: the gravity of the attacks on her push the idea of this being ‘all in her head’ about as far as they could conceivably go. In this respect, Martyrs seems to draw together a lot of the quite disparate threads which were drifting along together in horror cinema at the time, and it does so in a way which is quite unique and challenging.

Whilst ordeal horror was in the ascendant during this period, supernatural horror hadn’t gone away – but, with notable exceptions like The Orphanage, it was definitely undergoing something of a lull, perhaps doing best in the blink-and-miss-it terrors of Paranormal Activity, a supernatural horror which hardly bothers with supernatural horror. As found footage hit its stride, many filmmakers tried to invoke supernatural terrors – quite possibly simply out of a desire to find something new to film through a handheld camera – but refracted through a wheeling camera and often dreadful production, it rarely worked well after the initial surprise hit of Blair Witch. In many ways, then, supernatural horror was underused and underappreciated in the first decade of the new century, with many film fans having to look back, or look East, to find compelling supernatural horror. Martyrs dabbles with the supernatural in a unique way: it raises the spectre, modernises it, places it front and centre and then performs an about-face, revealing that all of the imagined bogeymen are real, Lucie’s hallucination is a manifestation of her own metaphorical demons, and that via what happens to Anna maybe – maybe – there is nothing out there beyond that. In so doing, it effectively combines different styles of horror, placing the psychological squarely into the physical and the visceral.

This cumulative approach now looks and feels like the moment the wave broke, when ordeal horror finally reached its zenith and, post-Martyrs, had nowhere truly compelling left to go. After Pascal Laugier skinned a woman to interrogate whether there was an existence of ours beyond us, further excursions into ordeal horror felt ever more flat and needless, even a bit desperate. I do believe Martyrs was widely-enough seen and appreciated – at least by horror fans – to have significantly contributed to this, though of course directors were always going to run out of ways to maim eventually, or at least, audiences were going to grow jaded about them. Perhaps fittingly then, if not happily, Martyrs seems to have hung heavily over Laugier’s career, with his subsequent offering The Tall Man going to ground very quietly – and his most recent release, Incident in a Ghostland, only very slowly garnering interest. The film that made his name continues to define him as a filmmaker, and there’s been no easy way around that; any momentum Martyrs could or should have offered was instead met with open-mouthed, uncomfortable silence – which is perhaps inevitable, given the horrendous, protracted violence and dismal conclusions it provided us.

Similarly, the world we continue to occupy is all too ready to grant us protracted violence and dismal conclusions, with our own spectres ready to rise up and greet us. Dig just a little, and you can find footage of human beings still being burned alive or executed for some thinly hopeful spiritual reason or transgression; if Martyrs’ most appalling scenes once seemed too extreme or absurd, then do they now, under a continued torrent of evidence which we have to work to avoid, rather than seek out? Any internet search does it. And, as our population ages (it’s notable that so many of the seekers in Martyrs are elderly) we are going to be brought up against the all-but-certain nothingness at the end of it all. As for networks of people tormenting and abusing children – well, it’s notable that the word ‘historic’ has now undergone a kind of pejoration, so often have we heard it in its new guise; it’s now often wedded to cases of organised child abuse going back decades, happening just beneath the surface of the everyday. In effect, life can be wonderful, but for so many it can be a bleak and thankless existence, and the film encapsulates perfectly that compulsion to find purpose, by whatever horrible means. I don’t mean to be trite here: Martyrs is, after all, just a film, but perhaps it has taken root because of the way it cast about for unpalatable elements in the real world and condensed them into a startling and – whatever your take on it – unforgettable horror movie.

Similarly, the world we continue to occupy is all too ready to grant us protracted violence and dismal conclusions, with our own spectres ready to rise up and greet us. Dig just a little, and you can find footage of human beings still being burned alive or executed for some thinly hopeful spiritual reason or transgression; if Martyrs’ most appalling scenes once seemed too extreme or absurd, then do they now, under a continued torrent of evidence which we have to work to avoid, rather than seek out? Any internet search does it. And, as our population ages (it’s notable that so many of the seekers in Martyrs are elderly) we are going to be brought up against the all-but-certain nothingness at the end of it all. As for networks of people tormenting and abusing children – well, it’s notable that the word ‘historic’ has now undergone a kind of pejoration, so often have we heard it in its new guise; it’s now often wedded to cases of organised child abuse going back decades, happening just beneath the surface of the everyday. In effect, life can be wonderful, but for so many it can be a bleak and thankless existence, and the film encapsulates perfectly that compulsion to find purpose, by whatever horrible means. I don’t mean to be trite here: Martyrs is, after all, just a film, but perhaps it has taken root because of the way it cast about for unpalatable elements in the real world and condensed them into a startling and – whatever your take on it – unforgettable horror movie.

This, perhaps, is a fitting place to end the discussion on Martyrs, and almost certainly – this time – the last thing I’ll feel the need to write about this film. But as we mark a decade since the film was released, and I suggest that Martyrs was the last true ordeal of the ordeal horror wave, it begs the question: if genuine horrors continue to encircle us as ordeal horror recedes, what’s next? Whilst many, brilliant horror films have been released in the years since Martyrs made such a stir, it’s not easy to say at the moment of writing whether any definite trends are emerging, at least not in the ways common to the new wave of European horror under discussion here. However, horror cinema has always found ways to symbolise and exaggerate our real life anxieties, birthing new genres or bringing old genres to new prominence. So, as many of the things brought to the screen in Martyrs keep us doubting a decade later, and as new real-life terrors inevitably come along, it will be fascinating to see how horror morphs and grows to reflect them. Films at their best – and worst – continue to have tremendous power, and Martyrs is absolutely a film which encapsulates this.