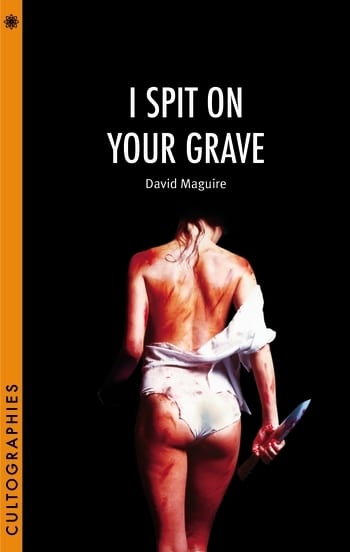

More and more these days, we’re seeing academic studies of what is often regarded as genre cinema; this ties in with the rise and rise of film studies more generally, with horror finally being regularly recognised and brought into the fold. In the past few months alone, for instance, I’ve reviewed books on The Shining, Don’t Look Now, A Company of Wolves and The Grudge. Given the origins of some of the films now receiving this treatment, you can only imagine just how far this new scholarly interest must be from anything the filmmakers ever imagined at the time, and where I Spit on Your Grave director Meir Zarchi is concerned, his film’s journey from execrable to esteemed has taken a very steep arc. Still, at their best these kinds of focused cinematic studies can successfully contextualise and hopefully interrogate notorious movies – which was my hope for David Maguire’s monograph on Zarchi’s 1978 film (hereafter known as ISOYG). As an additional tester, and one of the reasons I requested a review copy of the book, I’m by no means a fan of ISOYG; I was interested to see if the book would address any of the issues I have with the film overall and/or bring me around to its merits. Happily, this is the case.

More and more these days, we’re seeing academic studies of what is often regarded as genre cinema; this ties in with the rise and rise of film studies more generally, with horror finally being regularly recognised and brought into the fold. In the past few months alone, for instance, I’ve reviewed books on The Shining, Don’t Look Now, A Company of Wolves and The Grudge. Given the origins of some of the films now receiving this treatment, you can only imagine just how far this new scholarly interest must be from anything the filmmakers ever imagined at the time, and where I Spit on Your Grave director Meir Zarchi is concerned, his film’s journey from execrable to esteemed has taken a very steep arc. Still, at their best these kinds of focused cinematic studies can successfully contextualise and hopefully interrogate notorious movies – which was my hope for David Maguire’s monograph on Zarchi’s 1978 film (hereafter known as ISOYG). As an additional tester, and one of the reasons I requested a review copy of the book, I’m by no means a fan of ISOYG; I was interested to see if the book would address any of the issues I have with the film overall and/or bring me around to its merits. Happily, this is the case.

A slim volume of 140 pages altogether (including notes, filmography and bibliography), the book starts very promisingly. Making a firm case for the film’s uniqueness and the ‘pared down’ qualities which have been embellished (read: spoiled) in most of the subsequent entrants into the rape/revenge canon, Maguire then gets into the relevant history of 1970s and 80s America. The US at the time was immersed in significant changes to legislature and social movements impacting upon women’s rights, which can be seen to have led to male anxieties in response to their own shifting, jeopardised roles, which culminated in backlash. In this section, Maguire suggests that this spirit of backlash found expression in contemporary cinema; I’d agree with some of the examples he offers, but not with others (the human ‘meat’ in Texas Chainsaw Massacre does not for me represent anything significant about women, and conflating it with the infamous Hustler Magazine ‘meat’ cover doesn’t follow for me). Still, a rundown of the films which were released very close in time to ISOYG does indeed demonstrate that there was a cinematic seam of subjugated and abused women, which is interesting context.

Maguire then documents the history of the making of and release of ISOYG; happily, he pulls no punches here, noting the large disconnect between Zarchi’s professed noble intentions and the marketing of the film itself (though noting that bad publicity is still publicity, with the likes of Roger Ebert and the BBFC cementing the film’s reputation in ways which neither Zarchi nor Jerry Gross could have ever done. Oh, and whilst detailing the film’s retitling and releases in other countries, Maguire gives us the fun fact that in Ecuador ISOYG was renamed Suspiria 2: Killer Sharks, in a bold attempt to trade off both Argento’s original and the success of Jaws, and no doubt leading to many confused and disappointed viewers.

The debate set up in the chapter entitled ‘Filth or Feminism?’ covers engaging analysis of the film, balancing description of its defiantly non-salacious scenes against, again refreshingly, questions about Zarchi’s professed motivations and decision-making. For example, why did he say that Camille Keaton’s “slim delicate figure and […] soft ethereal beauty” made her so suitable for the character of Jennifer Hills? Maguire notes that rape/revenge films still opt for young, beautiful female characters, so it’s a valid concern here. Maguire also interrogates Zarchi’s claims of naivety over how the film would be received, given that he had courted controversy before.

In looking at the wealth of critical response between 1978 and the present, I was actually pleased to read about how Stephen R. Monroe (director of the first ISOYG remake) took issues with a key plot element in the original; that is, how a gang-raped woman uses consensual sex as part of her vengeance. That, far more than the notorious 25 minute attack scene, is the one which has always given me conniptions; having announced my bias, I’ll say that this section of the book is probably the most frank and revealing for me. Where Maguire reaches further, citing influences from mythology on the characters, setting and themes of ISOYG, I confess to being curious rather than wholly convinced – but then again, some of the women in rape/revenge films seem to acquire quasi-supernatural powers before they seek their revenge, which is itself every bit as unrealistic as Keaton’s Jennifer Hills going on her seduction drive in the original film.

The book follows with exhaustive research into the legacy of ISOYG. There are some genuine surprises here as Maguire identifies a number of very thematically similar films which have emerged since the ‘Ground Zero’ of the genre got its release (including a spoof?!) and then there’s a good long look at the merits and demerits of the remake/subsequent-to-the-remake films, which can be seen as a franchise. He’s very fair, offers a number of well-argued points in defence of ISOYG (2010) and goes some way to dispel what has turned into a dichotomy between original and remake: first film good, remake bad. He is, though, far less kind to the 2013 sequel, a film I cannot comment on as I avoided it like the plague…

The book follows with exhaustive research into the legacy of ISOYG. There are some genuine surprises here as Maguire identifies a number of very thematically similar films which have emerged since the ‘Ground Zero’ of the genre got its release (including a spoof?!) and then there’s a good long look at the merits and demerits of the remake/subsequent-to-the-remake films, which can be seen as a franchise. He’s very fair, offers a number of well-argued points in defence of ISOYG (2010) and goes some way to dispel what has turned into a dichotomy between original and remake: first film good, remake bad. He is, though, far less kind to the 2013 sequel, a film I cannot comment on as I avoided it like the plague…

As a worst-case scenario, this book could have been a very dry, very pompous meta-analysis of ISOYG which used lots of words to say little. Instead, I’ve been very pleasantly surprised. Maguire comes across as bright and personable, clever and focused without ever wallowing in jargon, and perhaps most importantly of all, aware that ISOYG is not a perfect film whilst still eminently worth of a closer look. A well-written piece of work, the book could easily reward fans as much as students and it’s well worth a place on the shelf. Now, we wait to see if Zarchi’s long-awaited official sequel to ISOYG actually does land this year…

I Spit on Your Grave by David Maguire is available now as part of the ‘Cultographies’ series from Wallflower Press.