Old Dark Houses are a horror cinema staple, bequeathed to the genre by Gothic literature, penny dreadfuls and all manner of other earlier terrors in print. Perhaps surprisingly, then, this particular Old Dark House (1932) is based on a J. B. Priestley novel, Benighted, written just five years previously. Priestley is better known for social realism than involvement in early horror cinema, but it’s after all via his story that we begin this trip through deepest, darkest Wales.

A bickering married couple, Philip and Margaret Waverton, together with a rather less-concerned and war-weary companion named Penderel, are on their way to Shrewsbury during a storm, in an era before cars came with windows. They’re cold, miserable and – soon – the worsening weather strands them at a remote house, where they’re forced to seek shelter. The inmates of this house are interesting folk, to say the least. The head of the household seems to be Horace Femm (Ernest Thesiger), who lives with his cantankerous, hard-of-hearing sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) and a voiceless servant, Morgan (Boris Karloff). After a small amount of disagreement on whether the three strangers should be allowed to stay or not, Horace assents, offering them hospitality in the form of a place at the fire, and a shot of gin. He’s a curious character: somewhat effete, definitely morbid but overall, fairly accommodating compared to his sister, who is soon regaling the guests with the awful godlessness of everyone who lives in the house, except her.

A strange night begins to unfold. Soon, two more travellers are hammering at the door, and they also get a grudging welcome. The conversation begins to flow, as does the booze – which isn’t a good thing where the thirsty butler Morgan is concerned. Oh, and then there’s the small matter of the elderly father ensconced upstairs (and is he the only person up there?)

As an exercise in atmosphere, and an important chapter in the rise of Universal Studios as an influential force in spooky cinema, The Old Dark House is very endearing. Director James Whale had already cut his teeth on the innovative use of sound and shadow in Frankenstein the year before, and although the film under consideration here is rather more subtle and realistic than that particular monster flick, it does bear a lot of the same hallmarks. The script here – closely following the novel – works a treat, with a terse, acerbic note throughout and some memorable lines, particularly from the character of Rebecca, who takes some time out from grumbling to mutter portentous lines to the terrified guests. But then there’s Horace Femm, whose every line and gesture here is a charm. Thesiger, contemporary and correspondent of ‘Great Beast’ Aleister Crowley, comes across as a cipher for a bygone age, all sardonic wit and rarefied manners. Karloff has little to do but loom and brawl in this film, but as ever, he has an enjoyable presence.

There’s more to this film than simply suspense and mild scares, mind, and one of the reasons it’s so engrossing is in how it sits squarely between the stage traditions of the late nineteenth century and the relatively new form of film. Interestingly, there’s a framed portrait of Queen Victoria in one of the bedrooms. Some of the scenes are positively vaudevillian in style, with a few physical jerks, lines played for laughs and that old chestnut, the partially-hearing character, who continually misinterprets what’s been said to them. Also, despite being an American production, the film feels charmingly British, too; the regular conversations about the bad weather are a dead giveaway, and then there is the range of visitors from different regions of the UK, including a heavily-stereotyped Yorkshireman who looks for all the world like a proto-Peter Kay (noting the fact that Kay is actually from the ‘wrong’ county next door). There are a few lines relating to the changing world of the mid-thirties, too, and although this isn’t exactly a film steeped in social commentary, there’s still mention of the world of “factories, and cheap advertising, and money-grubbing” going on far outside the house’s walls, as well as the war-damaged Penderel (Melvyn Douglas) who seeks something better for himself after this hellish night at the house is over and done with.

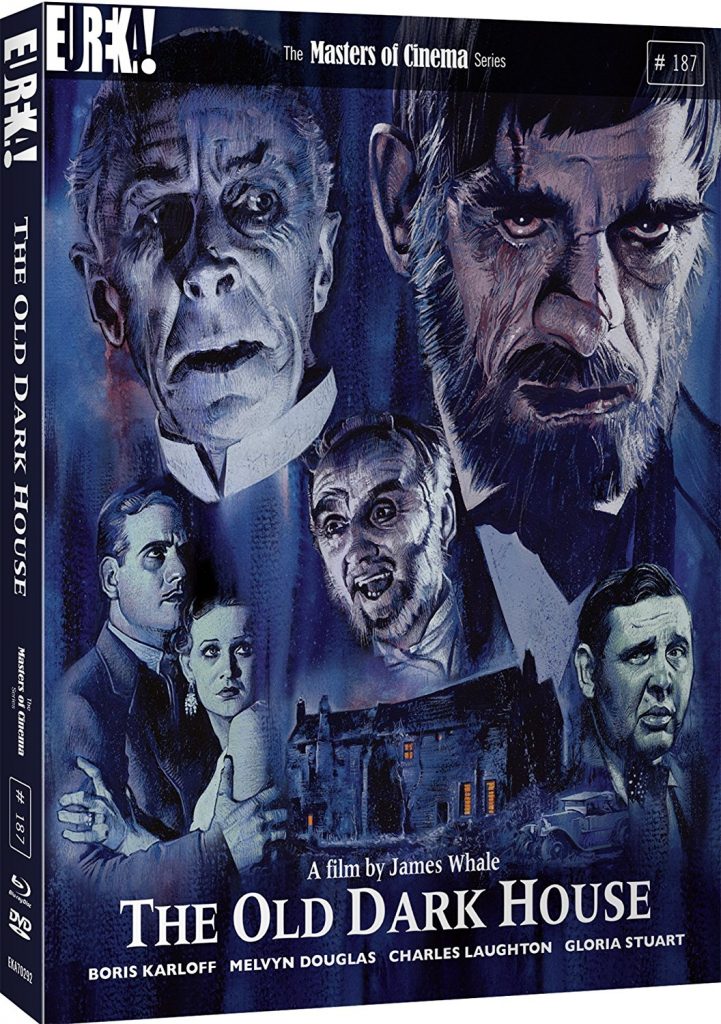

Although this may be a film which has little in common either thematically or stylistically with the vast majority of modern cinema and may seem like a reach for some, I still feel that it’s worthwhile for modern audiences. It’s a quaint melting pot of ambience, drama and classic cinema aesthetics in an unusual setting, as well as an engaging yarn and a cool film history lesson. Whilst The Old Dark House certainly isn’t the only old dark house out there (nor even the only film by that title) it’s nonetheless deserving of its reputation. The upcoming 4K Eureka release is of a very high quality, doesn’t look like a film which is around eighty-five years old, and comes with newly-commissioned artwork by established visual artist Graham Humphreys. If you’ve missed out on this one in the past, then this new deluxe edition would definitely come recommended.

The Old Dark House – 4K edition – will be released by Eureka Entertainment on 27th April 2018.